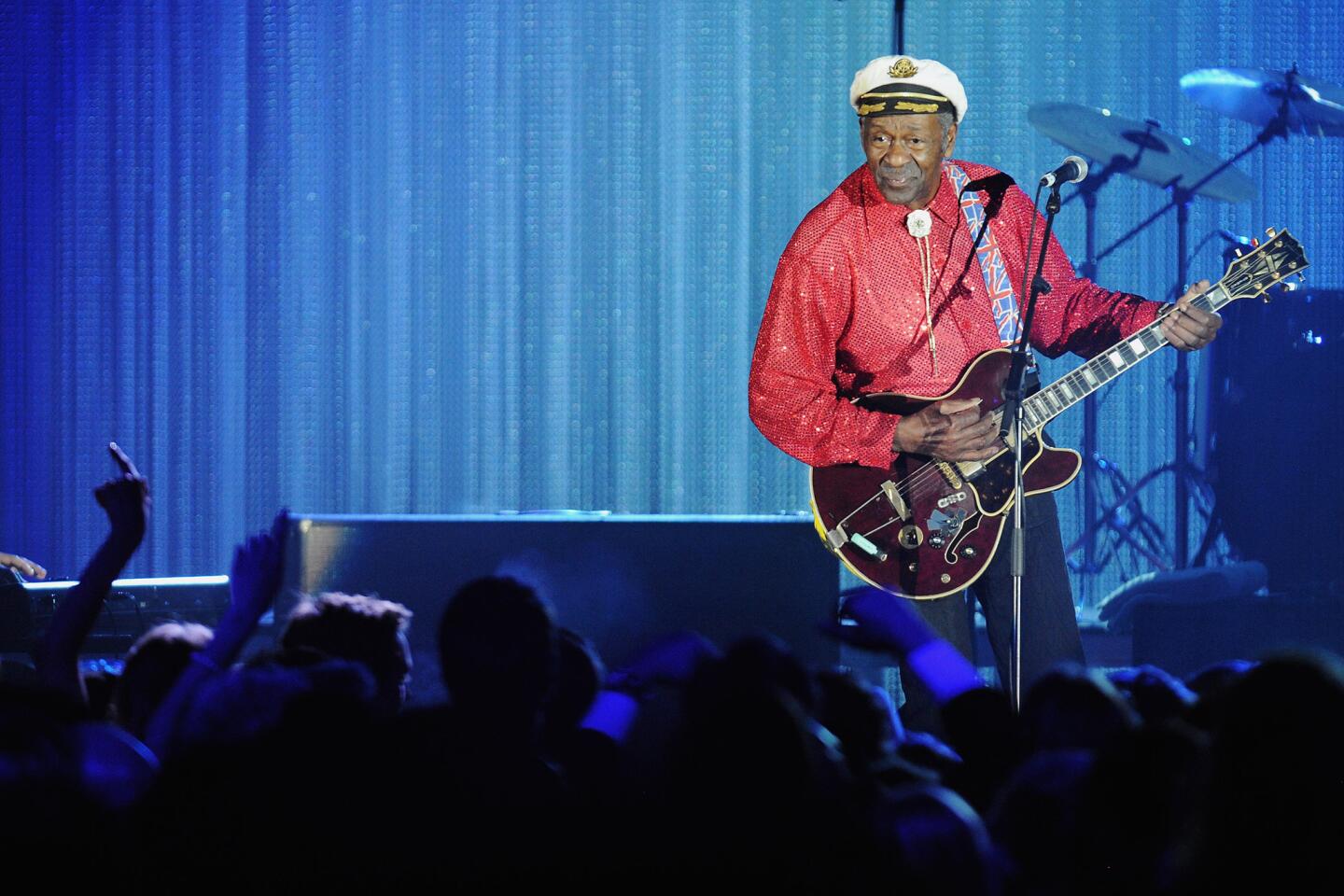

Chuck Berry dies at 90, a founding father of rock ‘n’ roll

In the early 1970s, more than a decade after rock pioneer Chuck Berry’s first round of fame and fortune was over, he was booked for an East Coast appearance, where he hired an aspiring group of young musicians to back him at the show. It was standard procedure for Berry over the years, his way of touring more economically than traveling with a full band.

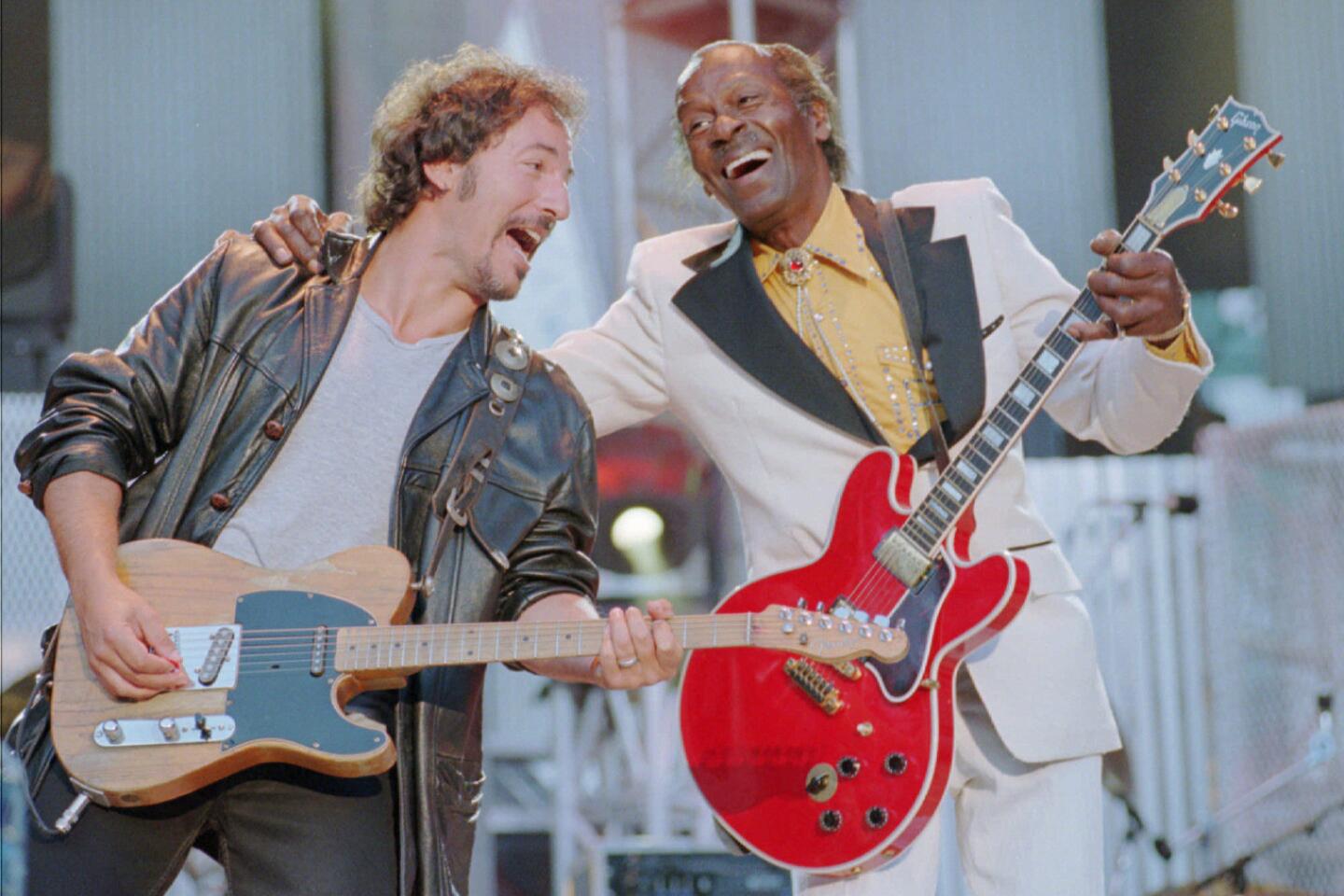

“About five minutes before the show was timed to start, the back door opens and he comes in,” Bruce Springsteen recalled years later. “[I said] ‘Chuck, what songs are we going to do?’ He says, ‘Well, we’re going to do some Chuck Berry songs.’ And that’s all he said!”

But it was all that needed to be said. As John Lennon, another disciple of the influential singer, guitarist and songwriter once said, “If you tried to give rock ’n’ roll another name, you might call it ‘Chuck Berry.’ ”

One of the founding fathers of rock ’n’ roll, an innovator who designed much of the music’s sonic blueprint and became his era’s most creative lyricist, Berry died Saturday in his native St. Louis. He was 90.

In hits such as “Maybellene,” “Johnny B. Goode” and “Sweet Little Sixteen,” Berry paired clarion guitar riffs and a relentlessly rhythmic blend of blues and country with buoyant vignettes celebrating teenage life and the freedom of 1950s America.

“He laid down the law for playing this kind of music,” Eric Clapton once said. “The Encyclopedia of Popular Music” states that Berry’s influence as a guitarist and songwriter is “incalculable.”

At a time when rock ’n’ roll lyrics were secondary to the sound of the records, Berry’s sophisticated depictions of adolescence — school, cars, growing up, courtship, the onset of adulthood — showed for the first time that the music could mirror and articulate the experience of a generation. In the mid-1950s, only the songwriting team of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller worked similar territory.

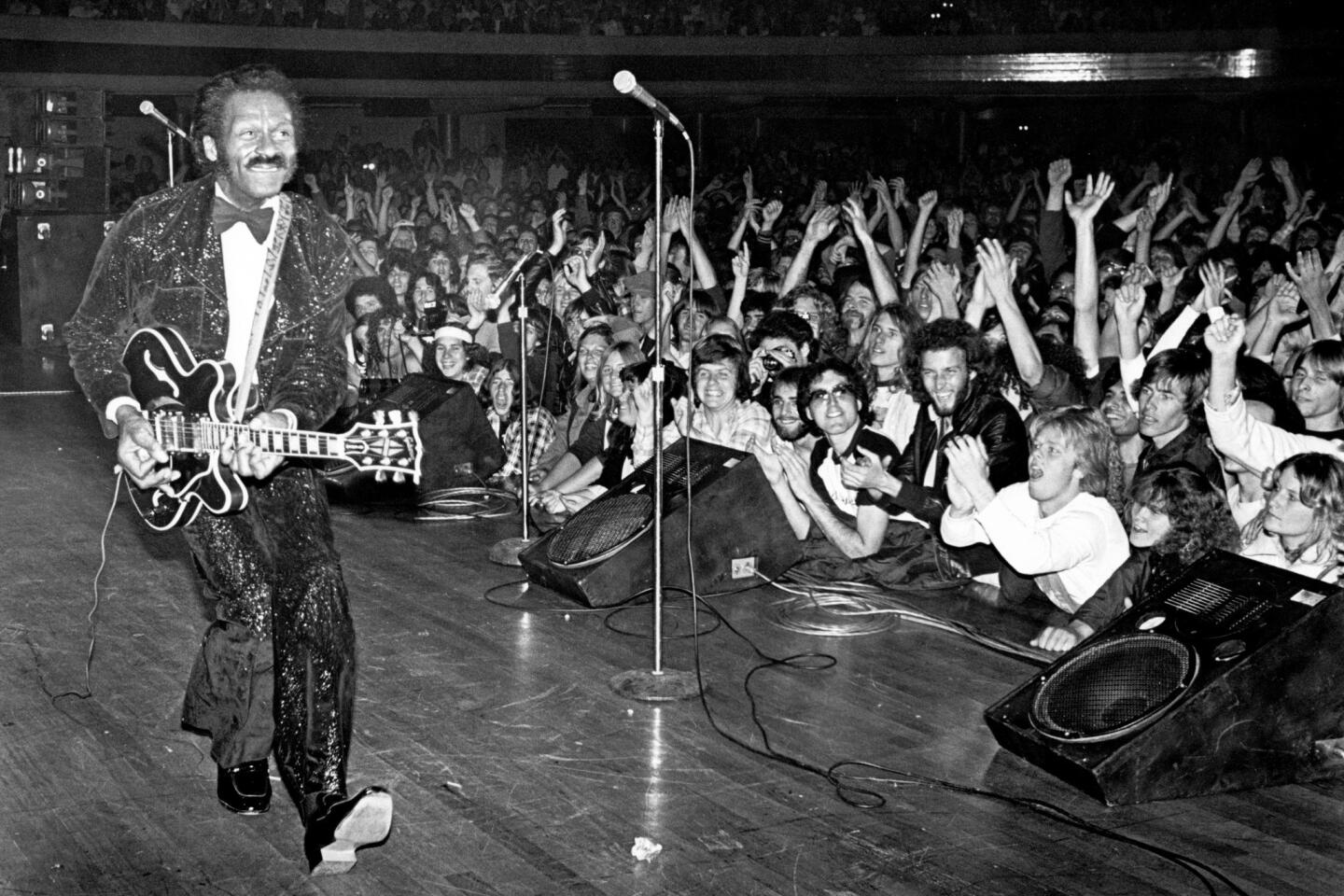

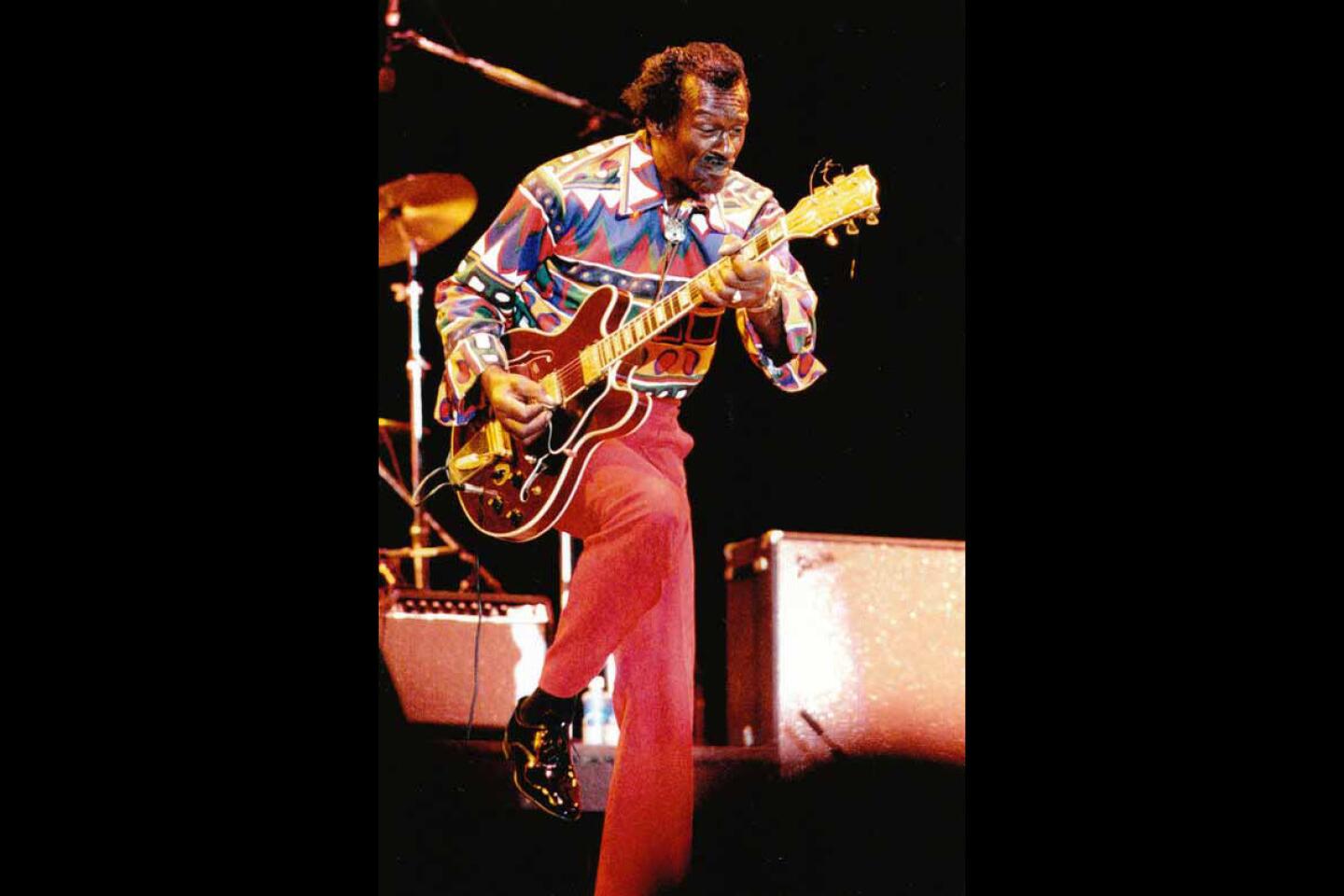

Widely hailed as rock’s original guitar hero for his flamboyant style of performance that helped push guitar into the forefront of the new musical genre, Berry was equally lauded for his lyrical creativity.

When Bob Dylan was still a teenager in Hibbing, Minn., in 1957, a classmate recalled mentioning Berry’s hit single “Maybellene” to the bookish young student. Echo Helstrom told author Clinton Heylin in his Dylan biography “Behind the Shades” that Dylan went “on and on about Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jimmy Reed — Bob thought he was fabulous. The best.”

Rolling Stones lead singer Mick Jagger said Saturday: “He lit up our teenage years and blew life into our dreams of being musicians and performers. His lyrics shone above others and threw a strange light on the American dream. Chuck, you were amazing, and your music is engraved inside us forever.”

Despite his profound musical influence, part of Berry’s legacy and his view of his place as a black man in a predominantly white man’s music world in the 1950s and ’60s were shaped by run-ins with the law. He served time for armed robbery as a teenager, and he was convicted of transporting a 14-year-old girl across state lines “for immoral purposes” in 1962 and of tax evasion in 1979.

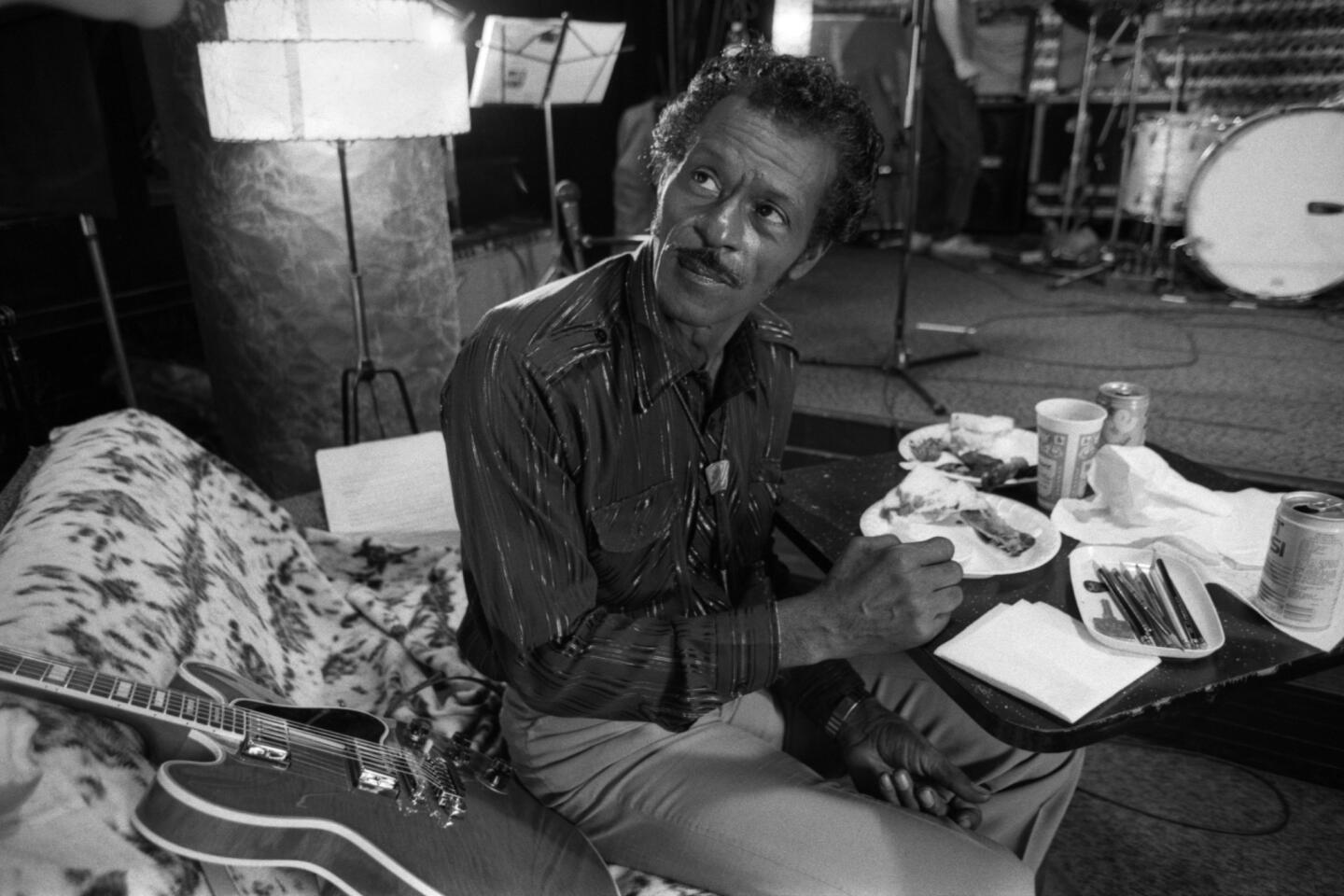

Those experiences are widely regarded as contributors to the guarded, difficult nature of Berry’s personality. He wrote an autobiography in 1987 and performed regularly for most of his life, but Berry granted few interviews and rarely revealed much of himself. In director Taylor Hackford’s 1987 documentary “Chuck Berry: Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’ Roll,” he is a complex character, alternately charming and controlling.

But when he did choose to speak on the record, he sounded every bit as articulate and literate as so many of his songs.

“One of my realizations is that if you revel over joy,” he told The Times in 2002, when he was 75, “you’re going to ache over pain and get killed over hurt. Your span of feelings are going to go just as far one way as the other. So when something real good comes to you, take it and chew on it....

“Then when something bitter gets in there, you won’t feel too bad chewing it and smiling, because the other one wasn’t that good, so this won’t be that bad,” he said, espousing a viewpoint in line with the ancient Greek Stoics. “That’s mathematical, and I think Einstein would have agreed with that.”

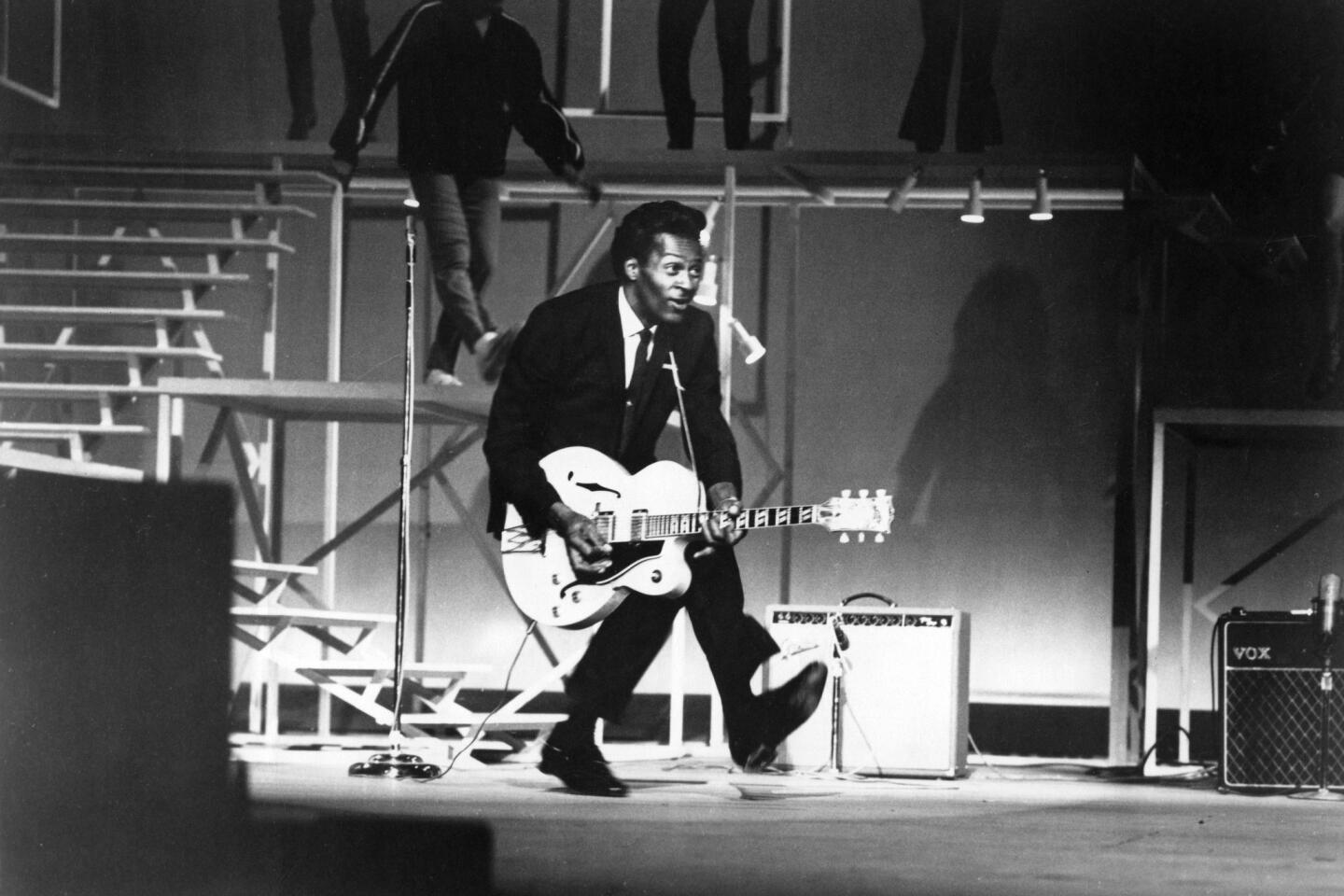

Berry had six Top 10 hits from 1955 through 1964 and was a dynamic force on the frenzied rock ’n’ roll tours of the ’50s, with his piercing gaze and famous “duck walk,” in which he crouched low and scooted across the stage with one leg extended and his guitar held high.

A host of followers embraced his sound and songs. The early albums and concerts of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones were peppered with such Berry works as “Rock & Roll Music,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Carol” and “Around and Around.” Their British Invasion peers, including the Animals and the Kinks, were similarly under his spell.

His fellow Americans were no less impressed. Berry’s “Memphis, Tennessee” became a hit for both Lonnie Mack (an instrumental version) and Johnny Rivers. The rapid phrasing and energy of “Too Much Monkey Business” was a model for Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues.”

The honor wasn’t always acknowledged. The Beach Boys’ 1963 hit “Surfin’ U.S.A.” was a near-copy of “Sweet Little Sixteen.” Berry, watchful over every dollar due, sued and won co-writing credit.

Similarly, the opening lines of the Beatles’ “Come Together” were close enough to a lyric from “You Can’t Catch Me” (“Here come a flat-top, he was movin’ up with me”) that Berry brought legal action and won a settlement.

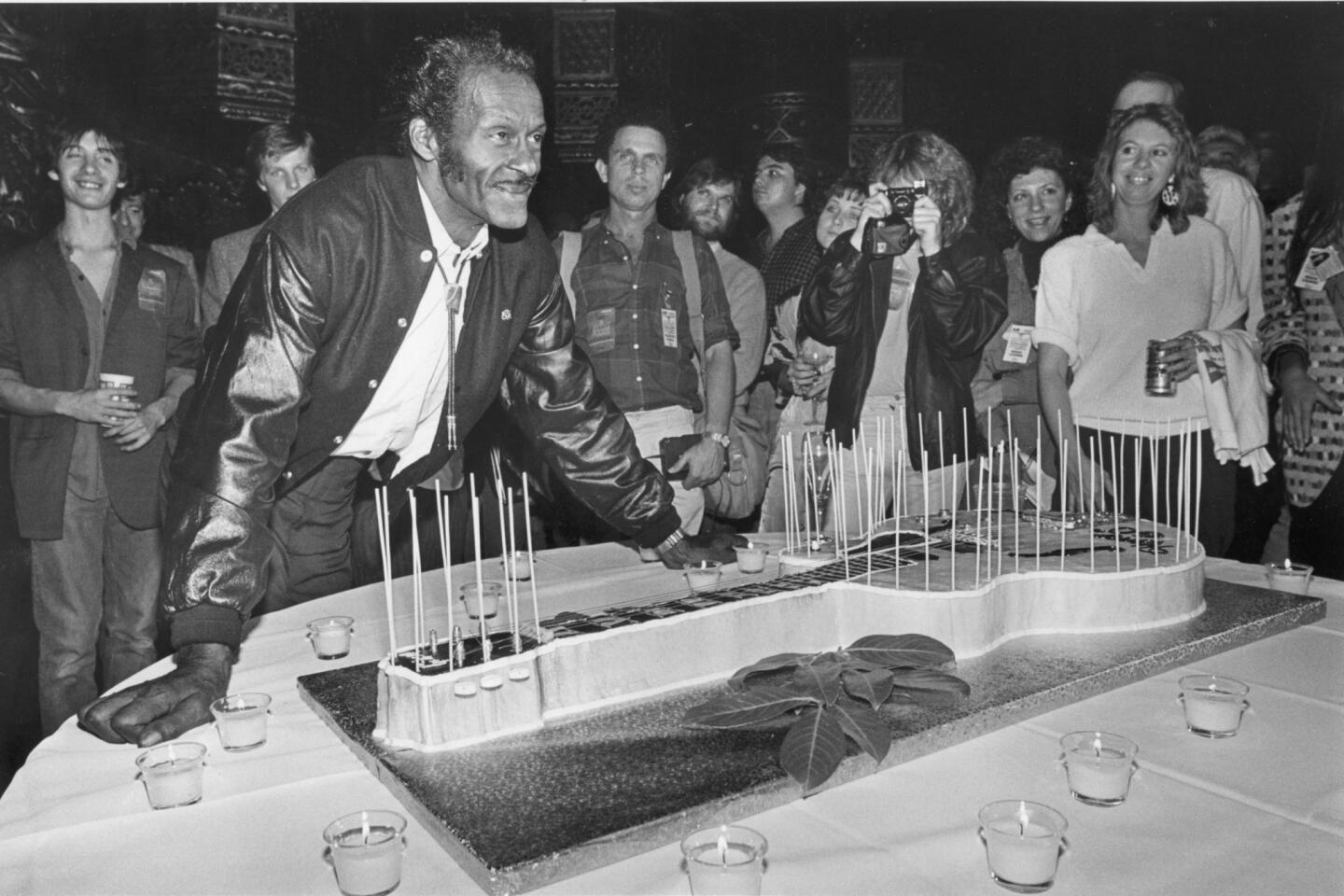

Berry was part of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s inaugural induction class in 1986. He received a lifetime achievement Grammy in 1984, was named to the Kennedy Center Honors in 2000 and received Sweden’s prestigious Polar Music Prize in 2014.

A recording of “Johnny B. Goode” was included among the cultural artifacts installed on the two Voyager space probes launched in 1977. On a subsequent “Saturday Night Live” sketch, comedian Steve Martin reported on the first communication from distant aliens: “Send more Chuck Berry.”

Charles Edward Anderson Berry was born Oct. 18, 1926, in St. Louis, one of six children. His mother, Martha, was a teacher, and his father, Henry, was a carpenter whose enthusiasm for poetry and other literature made a deep impression on his children.

The family enjoyed a relatively comfortable life in the black neighborhood known as the Ville, but Berry did encounter racism in other parts of town — he once recalled being turned away from the Fox Theatre downtown when he tried to buy a movie ticket.

Berry sang in a choir at a Baptist church and in the high school glee club. His taste for entertaining was sharpened when he turned in a well-received performance of “Confessin’ the Blues” at a high school talent show, and he soon took up the guitar.

When Berry was 17, he and two friends stole a car and robbed three businesses in Kansas City, Mo. Berry received the maximum sentence of 10 years. Inside the Intermediate Reformatory for Young Men in Algoa, Mo., he sang in a gospel group and learned to box, and he was released after serving three years.

Back in St. Louis, he worked at an auto plant and as a hairdresser, and supplemented his income by playing guitar in local bands. He married Themetta “Toddy” Suggs in 1948, and he and his wife would have four children.

Berry admired traditional pop standards and such singers as Frank Sinatra and Nat King Cole, and he loved big-band music and jump blues, especially the entertaining, often comedic brand of Louis Jordan. Jordan’s guitarist Carl Hogan was one of Berry’s instrumental models, along with Charlie Christian and blues stars Muddy Waters and T-Bone Walker.

Berry joined the Sir John Trio in 1952, teaming for the first time with pianist Johnnie Johnson, who would become an indispensable sideman on Berry’s records. They performed blues and ballads, and also adapted country tunes into a “black hillbilly” style that proved very popular. They started drawing big crowds at the Cosmopolitan Club in East St. Louis, Ill., and the band’s name was soon changed to the Chuck Berry Trio as the singer-guitarist asserted his dominance.

In 1955, Berry headed to Chicago to meet one of his heroes, Muddy Waters. After a show, Berry got an autograph from the blues great and asked for advice about making a record. Waters told him to contact Leonard Chess, the head of the famed blues label Chess Records.

Berry did, and he returned in a week with a demo tape. Chess took the trio into the studio and drove them through repeated takes of “Ida Mae,” Berry’s reworking of the folk tune “Ida Red.” Chess thought it had potential, but he had problems with the title. A box of mascara on a windowsill gave him his inspiration, and he renamed the tune “Maybellene.”

The record came out in July 1955 and reached No. 5 on the pop singles chart. The success was accompanied by a cold slap of reality. The songwriting credit on the record went not to Berry alone, but also to influential disc jockey Alan Freed and to the owner of the building that housed Chess Records. Such maneuvers were common in the record business then, but Berry was taken aback. After a long fight, he was finally granted sole credit in 1986.

More hits followed, records that became essential pillars of the rock canon: “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Rock & Roll Music,” “School Day,” “Johnny B. Goode,” “Sweet Little Sixteen.”

Their common thread was the exuberance of Berry’s sound and his vivid, lively language. His lyrics chronicled youthful culture with a keen, pithy eye, and his characters were constantly in motion, either around the dance floor, across the map or on the highway — inevitably in a Coupe de Ville, a V8 Ford, a “coffee-colored Cadillac” or some other big American car.

Singing with a sharp, precise enunciation, he could drop in a French phrase, coin words such as “motorvatin’ ” and craft indelible images — describing a girl who “wiggles like a glowworm, dance like a spinning top,” or colorfully capturing the excitement of rock ’n’ roll: “You know my temperature’s risin’ / And the jukebox blowin’ a fuse.”

He had the audacity to be a black man who wanted to get out there and perform for white kids and seduce white women, and he did.

— Taylor Hackford, documentary filmmaker

Despite being stung by racial prejudice in his life, Berry basked in a positive vision of his country in his songs. “New York, Los Angeles, oh how I yearn for you,” he sang in “Back in the U.S.A.,” longing from abroad for the place “where hamburgers sizzle on an open grill night and day.”

Berry also tested the waters of social commentary. “Brown Eyed Handsome Man,” a playful but potent statement of racial pride, opened with the wry line, “Arrested on charges of unemployment ….”

And “Too Much Monkey Business,” with its torrent of complaints (“Runnin’ to and fro / Hard workin’ at the mill / Never fail, in the mail / Yeah, come a rotten bill”), expressed the frustrations of a beleaguered breadwinner with a comical edge.

Berry showed that pop could be art, but he always insisted he was being merely pragmatic.

“I wrote about cars because half the people had cars, or wanted them,” he said in a 2002 interview with London’s Independent newspaper. “I wrote about love, because everyone wants that. I wrote songs white people could buy, because that’s nine pennies out of every dime. That was my goal: to look at my bank book and see a million dollars there.”

Berry had opened a nightclub and was riding high in 1959 when he was charged with violating the Mann Act, a federal law that prohibits the interstate transport of women for “immoral purposes.” The prosecution stemmed from Berry’s relationship with 14-year-old Janice Escalante, whom he had met in Juarez, Mexico, and brought to St. Louis. When he fired her from her job as a hat checker at the club, she went to the police.

Berry’s first conviction was voided because of racially based misconduct by the judge, but he was convicted in a second trial and sentenced to three years in prison in October 1961.

Many felt that Berry’s race and his history of relationships with white women were a factor in the prosecution. Racial dynamics would be a subtext throughout his career, in which he helped bring down the black-white divisions in popular music and specifically set out to appeal to a white audience.

“He was a rebel, a guy who was incredibly complex, unbelievably thorny, and through his own headstrong nature and his own appetites was truly punished for his rebellion,” said Hackford, who formed a stormy relationship with Berry when he directed the 1987 documentary.

“He had the audacity to be a black man who wanted to get out there and perform for white kids and seduce white women, and he did, and he was punished for it,” Hackford said. “... If rock ’n’ roll wants to lay claim to the music of rebellion, he led the charge.”

Berry was released after 20 months and returned to the charts with three more notable songs: “Nadine (Is It You?),” “No Particular Place to Go” and “Promised Land.”

That was the end of his significant record-making (his only No. 1 hit would come in 1972 with the risqué novelty cover “My Ding-a-Ling.”) But with the British Invasion bringing new attention to his legacy, Berry was a popular touring attraction. He appeared in the famed 1964 TAMI Show concert film, and as the decade proceeded he adapted to the counterculture’s festival and ballroom conventions.

He also collected cars and invested shrewdly in St. Louis real estate, and, less shrewdly, opened an amusement park called Berry Park. When it failed, the estate became Berry’s home and headquarters. (“I wanted it to be like Disneyland or Six Flags,” he once said, “but it turned out to be One Flag.”)

In the 1970s he participated in rock ’n’ roll revival tours, and after ending his relationship with his longtime band, including pianist Johnson, he began his practice of hiring a local group to wing it behind him in each city. Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band once had the honor in their early days, but the overall result was inconsistency, and Berry’s reputation suffered.

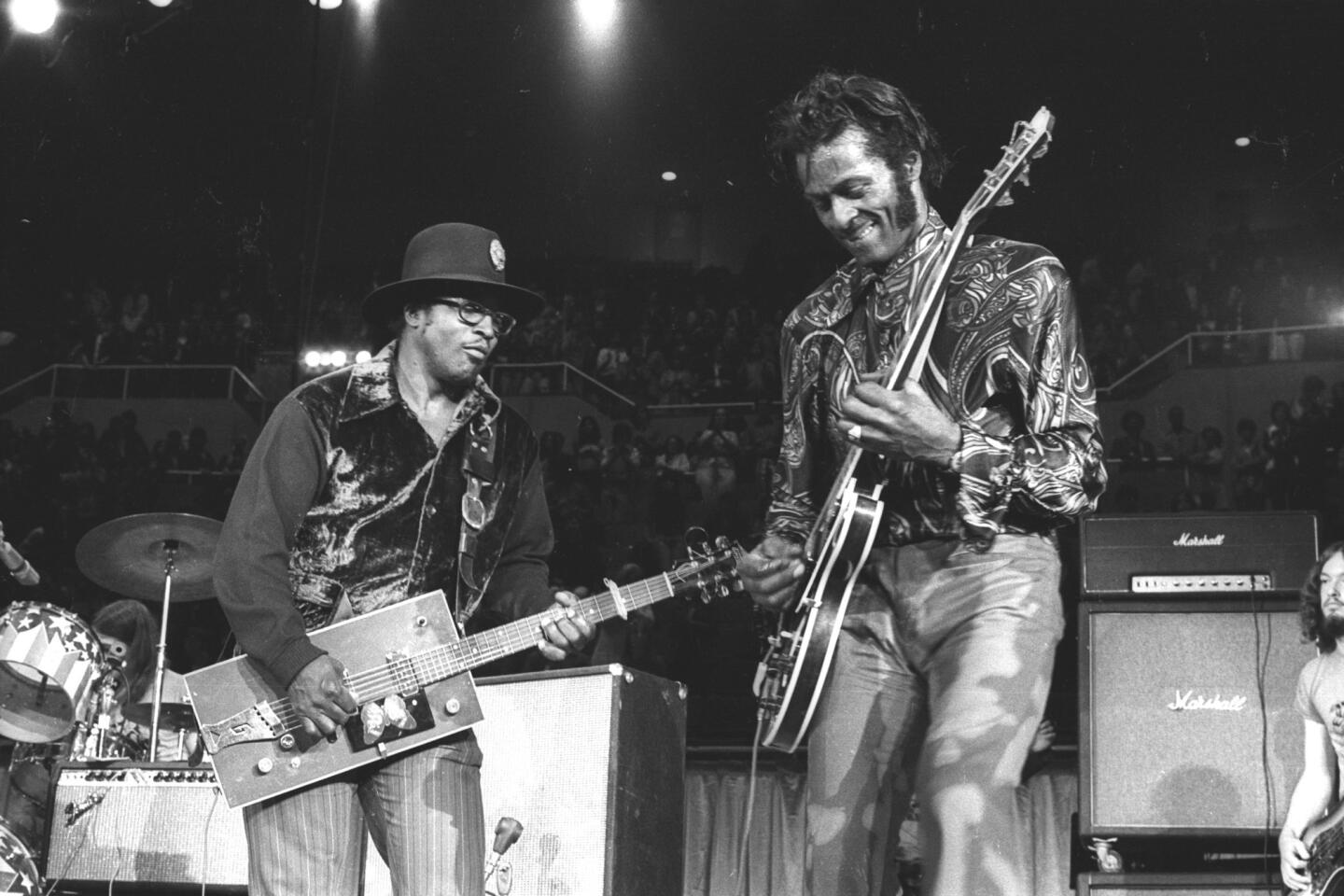

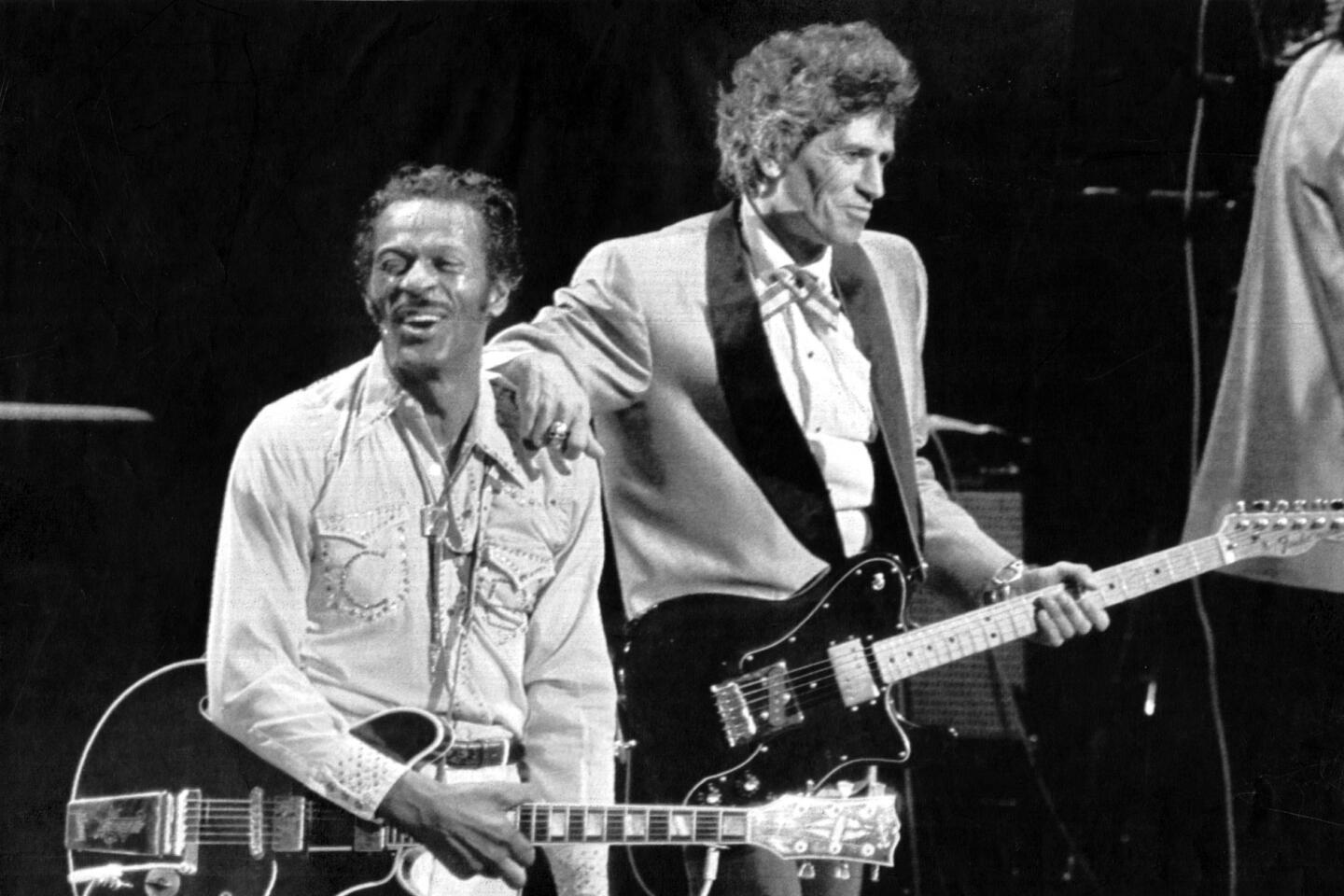

He played himself in the 1978 film “American Hot Wax,” which told the story of disc jockey Freed. Hackford’s documentary, in which Keith Richards led an all-star band behind Berry in concert with such guests as Clapton and Linda Ronstadt, put him back in the spotlight. Although Berry spoke periodically about recording new material, nothing came of it.

But he kept playing, making a monthly appearance at the Blueberry Hill club in St. Louis as recently as this summer.

There were more legal dramas. He served four months in federal prison in Lompoc in 1979 for income tax evasion. In 1990, 60 women sued him for allegedly videotaping them in the bathroom of a restaurant at Berry Park. Berry denied the charges but paid a settlement. And in 2000, Johnson sued him for royalties and credit, claiming the pianist had co-written Berry’s hits. The court ruled against Johnson, who died in 2005.

Mike Campbell, lead guitarist for Tom Petty’s band the Heartbreakers and himself one of the most respected rock guitarists of the last 40 years, spoke as a fan on Saturday when he said in a statement: “My heart is broken to hear Chuck is gone. He was my first and greatest inspiration.”

“Luckily, I met him once,” Campbell noted. “Shaking his hand was like slipping into a huge, warm baseball glove. The world will always remember and honor his amazing talent … writing, singing, playing guitar, and creating a genre — rock and roll. He is the true genius who paved the way for all those who chase the rock and roll dream. His music will never die.”

Invoking the title of Berry’s sequel to perhaps his most iconic hit, “Johnny B. Goode,” Campbell concluded, “Bye Bye, Johnny B. Goode.”

Times staff writer Randy Lewis contributed to this report.

MORE OBITUARIES

Joni Sledge, of ‘We Are Family’ group Sister Sledge, dead at 60

Blues harmonica player James Cotton, Mr. Superharp, dies at 81

UPDATES:

7:40 p.m. This article was updated with additional details and comments on Chuck Berry’s life.

This article was originally published at 3:25 p.m.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.