Ross Perot, Texas billionaire and former presidential candidate, dies at 89

A diminutive billionaire from Texas with a salty personality and a public persona as a straight talker, H. Ross Perot blazed across America in the 1990s as the maverick, third-party presidential candidate who won over nearly one out of every five voters with his flip charts, pointers and easy cures for the country’s dour economy.

He was an unlikely White House candidate, saddled with a gravelly voice and big ears easily caricatured by TV comics, and no campaign experience before he launched his uphill presidential bid.

But his algorithms for repairing the economy, preventing jobs from leaving the country and untangling the gridlock he claimed was paralyzing Washington appealed to voters who disdained the perfectly calibrated quotes and focus groups of professional politicians and their consultants.

Candid, colorful and cantankerous until the end, Perot died Tuesday after a five-month battle with leukemia, according to a family spokesman. He was 89.

“In business and in life, Ross was a man of integrity and action. A true American patriot and a man of rare vision, principle and deep compassion, he touched the lives of countless people through his unwavering support of the military and veterans and through his charitable endeavors,” James Fuller, a representative for the Perot family, said in a statement.

In his 1992 campaign, Perot captured nearly 19% of the popular vote but no electoral votes, and thus had no effect on the final results. Democrat Bill Clinton won the race against the incumbent president, George H.W. Bush.

During the first debate with Bush and Clinton, the 5-foot-6 Perot delivered a surprisingly strong performance. Using pithy one-liners and a no-nonsense attitude, he contrasted sharply with his rivals and their practiced delivery, zeroing in on the sour state of the economy and voter distrust of Washington. Most analysts said afterward he had won the debate.

In the second debate, Perot cemented his spot in the history of political one-liners when he predicted the North American Free Trade Agreement would create “a giant sucking sound going south” as business leaders moved jobs to lower-wage nations such as Mexico.

He mounted another insurgent presidential bid in 1996, but that one fell far short of the 1992 effort, ending his run on the national political stage.

Former President George W. Bush, whose father had clashed with Perot, praised his fellow Texan on Tuesday as a maverick.

“Texas and America have lost a strong patriot,” Bush said in a statement. “Ross Perot epitomized the entrepreneurial spirit and the American creed. “

Perot later helped finance controversial efforts in the 1970s and ’80s to find and rescue U.S. prisoners of war he believed were being held captive in Vietnam years after the war had ended there. Despite widespread speculation, none ultimately were found and a Senate investigation found “no compelling evidence” that any existed.

He also won fame for financing a rescue operation of workers for his company Electronic Data Systems who had been taken captive in Iran on the eve of the 1979 revolution.

It didn’t hurt Perot’s popularity that his rags-to-riches life reflected an American archetype, the self-made man who, through vision and grit, amassed a vast personal fortune.

Perot was an early tech entrepreneur who founded Electronic Data Systems, his first computer services company, in 1962 with $1,000 in savings. It later became an industry leader.

Even in failure, Perot seemed to have a golden touch.

In 1986, two years after General Motors bought EDS for $2.5 billion and gave Perot a seat on the board in hopes his entrepreneurial skills and spirited style would reinvigorate the bureaucracy-heavy corporation, the auto giant essentially paid him $700 million more to go away.

“Revitalizing GM,” Perot said before departing, “is like teaching an elephant to tap dance. You find the sensitive spots and start poking.”

Henry Ross Perot was born June 27, 1930, in Texarkana, Texas, to Gabriel Elias Perot, a cotton broker, and Lulu May Perot, a secretary for a small lumber company. Both his parents were regarded as strict, and they instilled the Methodist religious faith and a sense of personal ethics in their children.

Perot began working at age 7 and, over time, tamed horses, sold garden seeds and magazines, delivered newspapers and sold classified ads, and became a trader in horses and horse gear. He also became an Eagle Scout, a point of pride in his adult life.

As a child, Perot was a diligent, if not gifted, student, relying on hard work and a stubborn streak of competitiveness to get good grades.

“If we had to learn the Roman numerals, Ross would learn them and know them better than anybody else,” childhood friend Hayes McClerkin told the New York Times in a 1996 profile. “When it took dedication and persistence, he was always crossing the goal line ahead of people who probably were smarter. He would achieve simply because he would be more dedicated and disciplined.”

Perot attended Texarkana Junior College, where he was elected class president, then in 1949 received an appointment to the United States Naval Academy, where he also was twice elected class president.

While studying at Annapolis, he met Margot Birmingham, a student at Goucher College in Baltimore. They married in 1956 and had five children.

Perot graduated from Annapolis, 454th out of 925 cadets, in 1953. He served four years in the Navy, becoming an assistant fire control officer aboard the destroyer Sigourney.

In 1957, Perot joined IBM as a salesman. But IBM’s corporate culture proved too inflexible for him, and after the company rejected his proposal to help customers better use the computers IBM sold them, Perot quit and formed EDT to do just that.

“It became more and more obvious to me — people were buying the hardware, but they didn’t know how to use it,” he once said. “What they really wanted were systems that worked.”

Perot quickly built EDS into a powerful outsourcing firm, taking on a wide range of clients but heavy on government contracts, including Medicare and Social Security. The radical Ramparts magazine in 1968 dubbed him “America’s first welfare billionaire.”

Perot made it a point to hire Korean War veterans and imposed a conservative dress code — dark suits over white shirts, and no facial hair.

“We put a very high priority to hiring people coming right off the battlefield,” Perot said in Gerald Posner’s 1996 biography, “Citizen Perot: His Life and Times.”

“They were 27 years old, and 40 in terms of maturity. And no matter how much of a load we placed on them in the training program — and we tried to make it very rigorous — this was a huge cakewalk for them. Nobody was shooting at them. And they knew what stress was — not getting shot at was not being under stress.”

EDS built a reputation for doing the impossible, and doing it quickly. One client, Frito-Lay, hired EDS to install a computer system with a two-year deadline. EDS finished in two months. Twenty-hour workdays weren’t uncommon for employees in the midst of projects. But Perot was generous with high performers, who developed a fierce sense of loyalty.

Perot maintained tight control of the privately held firm, but in 1968 he took it public. Overnight he was worth $350 million and landed on the cover of Forbes magazine, which called him the “fastest, richest Texan.” Perot likened the windfall to “being hit by a comet.”

In 1984, Perot agreed to sell EDS to GM in return for cash and GM stock and a seat on the board. GM chief Roger Smith thought the corporate merger would revolutionize the auto giant’s legendarily slow-to-turn management system. And he hoped Perot would add entrepreneurial zeal to the board.

But clashes arose over a variety of issues including stock options and lines of responsibility, said Doron P. Levin, a Detroit journalist and author of “Irreconcilable Differences: Ross Perot Versus General Motors.” Perot soon became publicly derisive of GM’s management style and recalcitrance, and the corporate marriage failed.

In 1988, Perot was back in business with his Perot Systems Inc., a computer services firm focusing on the healthcare industry. His son succeeded him as chairman in 2004, and the computer giant Dell bought the firm in 2009 for $3.9 billion. At the time of his death, Perot’s net worth was put at $4.1 billion by Forbes.

But it was Perot’s forays into policy and politics that brought him the most notice.

In 1969, Perot met with top aides to President Richard M. Nixon, whose 1968 campaign he supported, to discuss the inhumane treatment of American POWs in North Vietnam. That winter, he spent $2 million to rent two jets, which he filled with medicine, Christmas presents, letters and other goods for the POWs. The goodwill flights were rebuffed by the North Vietnamese, but some of the POWs later said their living conditions improved after Perot’s effort.

Perot engaged in more direct action in February 1979 after two EDS workers in Iran were taken prisoner at the start of the Iranian Revolution that deposed the American-backed shah and created an Islamist state. Perot put together a rescue operation that involved a fake prison riot that diverted guards and allowed the two men to escape. The incident led to Ken Follett’s bestselling “On Wings of Eagles,” and an ensuing television miniseries.

Perot continued to press the issue of the fate of missing soldiers in the 1980s, leading private investigations into government actions and policies, and eventually accusing federal officials of a cover-up. In 1989, he engaged in direct secret talks with Vietnamese leaders with the blessing of the Reagan administration, but little came of it.

Despite his public persona as a straight-talking moralist, Perot was dogged by allegations that he engaged in personal vendettas. They included threats of using compromising photographs against political opponents; paying a Washington law firm $10,000 to investigate a $48-million tax break given to Pennzoil, run by a former business partner of George H.W. Bush; and investigating rumors that President Reagan and Bush, his running mate and former CIA director, had engineered a delay in the release of American hostages held in Iran until after the 1980 election.

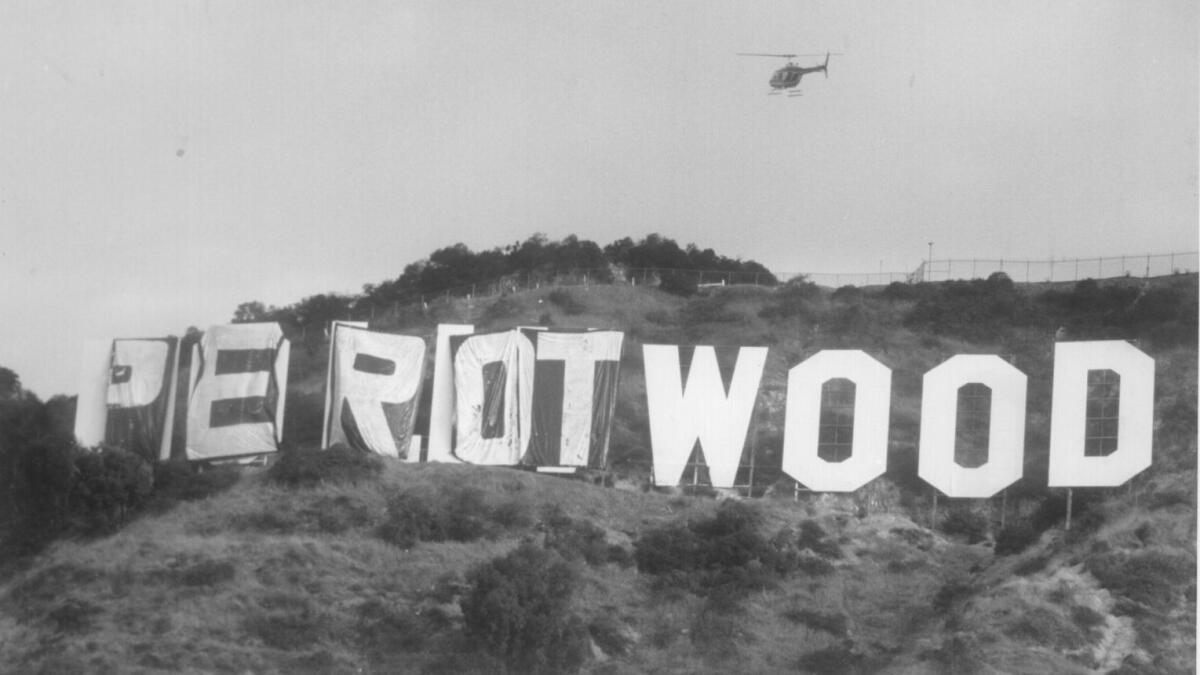

Perot said he liked to “stir things up,” and he did so with historical flair on March 16, 1992, when he announced on CNN that if supporters did the legwork to get him on the ballot in all 50 states, he would mount a third-party campaign for the White House.

By July he had backed off the pledge and said he wasn’t running, but supporters kept working on the petitions, and by October, Perot had jumped back into the race. He lost credibility by saying he had dropped out because Republican dirty-tricks operatives had threatened to release compromising photos of one of his daughters, a claim never substantiated.

He financed the campaign himself and aired TV infomercials about the economy, the NAFTA trade deal with Canada and Mexico, and other issues. In the end, exit polls showed he had drawn equally from supporters of Bush and Clinton. Although he gave voters an alternative to the two main political parties, in the end he had no influence on the outcome.

Perot founded the Reform Party in 1995 and ran again for the presidency in 1996, this time accepting donations. But the campaign floundered and Perot was excluded from the presidential debates. He received only 9% of the national vote in an election that Clinton won handily over Republican challenger Robert Dole.

In 2008, Perot’s wife and five adult children donated $50 million to Dallas’ Museum of Nature and Science at Fair Park — the product of a 2006 merger of three museums: the Dallas Museum of Natural History, the Science Place and the Dallas Children’s Museum. Because of the Perots’ hefty donation, the museum was able to move to a new, larger location in Victory Park, which broke ground in 2009. The 5-acre, $185-million museum, designed by Thom Mayne, was renamed the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in honor of the Perot family.

While the museum was considered a gem, its architecture was dismissed as “pricey, preening and old breed” by former Los Angeles Times architectural critic Christopher Hawthorne.

In recent years, Perot lived quietly in the Dallas area, in some ways trying to live out a dream he outlined after GM bought him out.

“See, I’m going to do whatever I want to do with the rest of my life,” Perot told the Washington Post in early 1987, a few months after leaving GM. “And in the end, well, there was this guy here in south Texas named Hondo Crouch who died in Luckenbach, Texas, dancing with a pretty girl when he was 94. Now my dream is to die dancing with my wife, Margot, when I’m 94. Ninety-four or beyond.”

Perot is survived by his wife Margot; sister Bette; son Ross Jr.; daughters Nancy, Suzanne, Carolyn and Katherine; 16 grandchildren; and three stepgrandchildren.

Times staff writer Dorany Pineda contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.