George H.W. Bush dies; 41st U.S. president saw the Cold War end

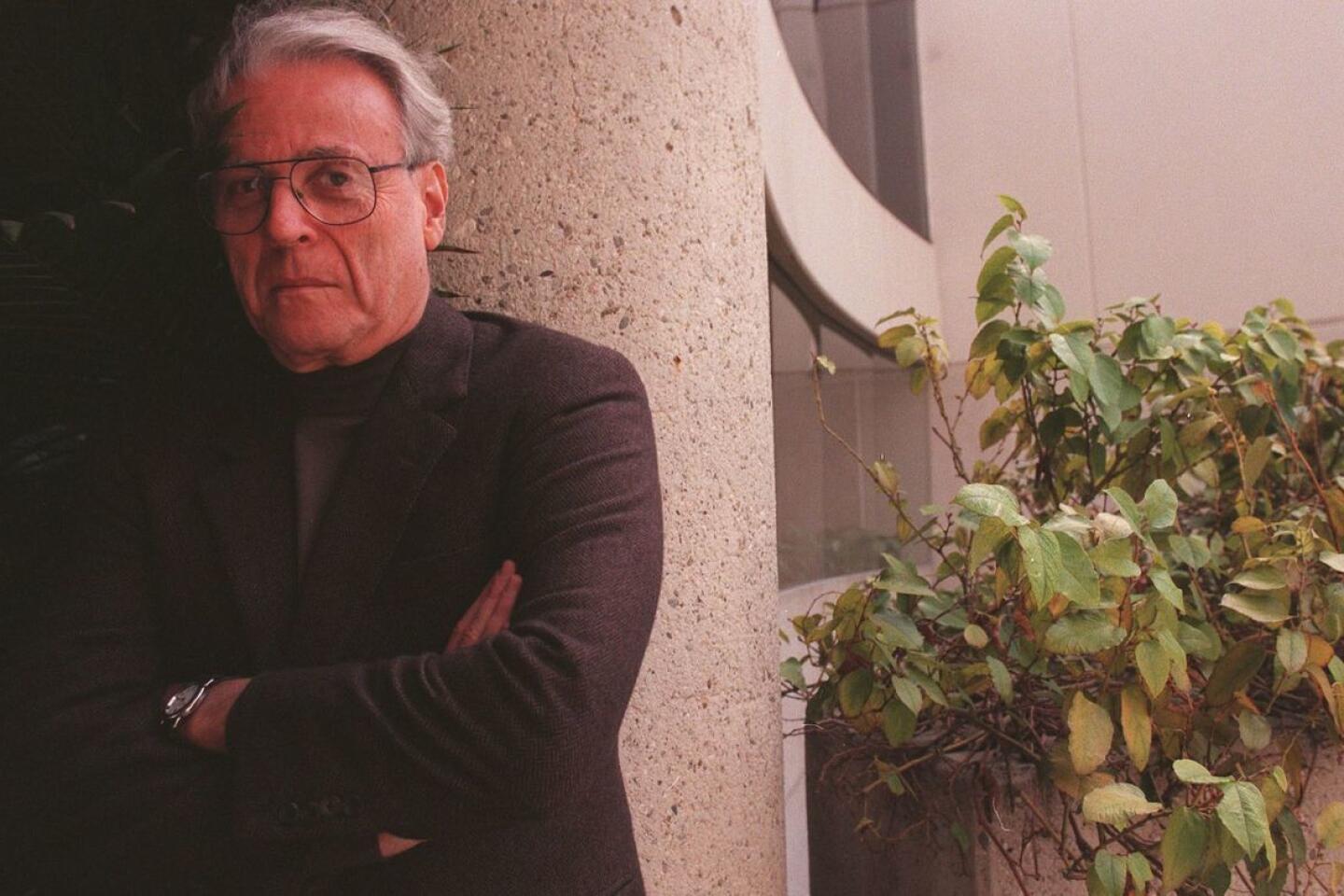

George Herbert Walker Bush, the linchpin of an American political dynasty and 41st president of the United States, who rode foreign policy triumphs to high popularity at the end of the Cold War only to suffer a revolt in his own party and a painful defeat for reelection, died Friday night at his Houston home. He was 94.

During his single term in the White House, the Berlin Wall fell, newly democratic states sprang up across Central and Eastern Europe, and the Soviet Union came to an end. And in the Middle East, the U.S. military launched its most successful offensive since World War II.

For the record:

10:55 a.m. Dec. 1, 2018A previous version of this article listed Bush’s brother William as a survivor. William Bush died earlier this year. George H.W. Bush also had eight great-grandchildren, not seven.

But the end of the Cold War also signaled the end of an era of American bipartisanship that the long conflict with the Soviets had fostered. Bush, the product of an earlier era, seemed out of phase with a younger, harder-edged generation of conservatives rising in his party.

When he broke a pledge not to raise taxes, they turned against him. He would end up humbled, buffeted by economic decline, then defeated for reelection in 1992, receiving less support than any incumbent president in 80 years.

The chasm between Bush’s achievements and his standing with the American public is a paradox that defines but doesn’t fully explain the legacy of the 41st president of the United States.

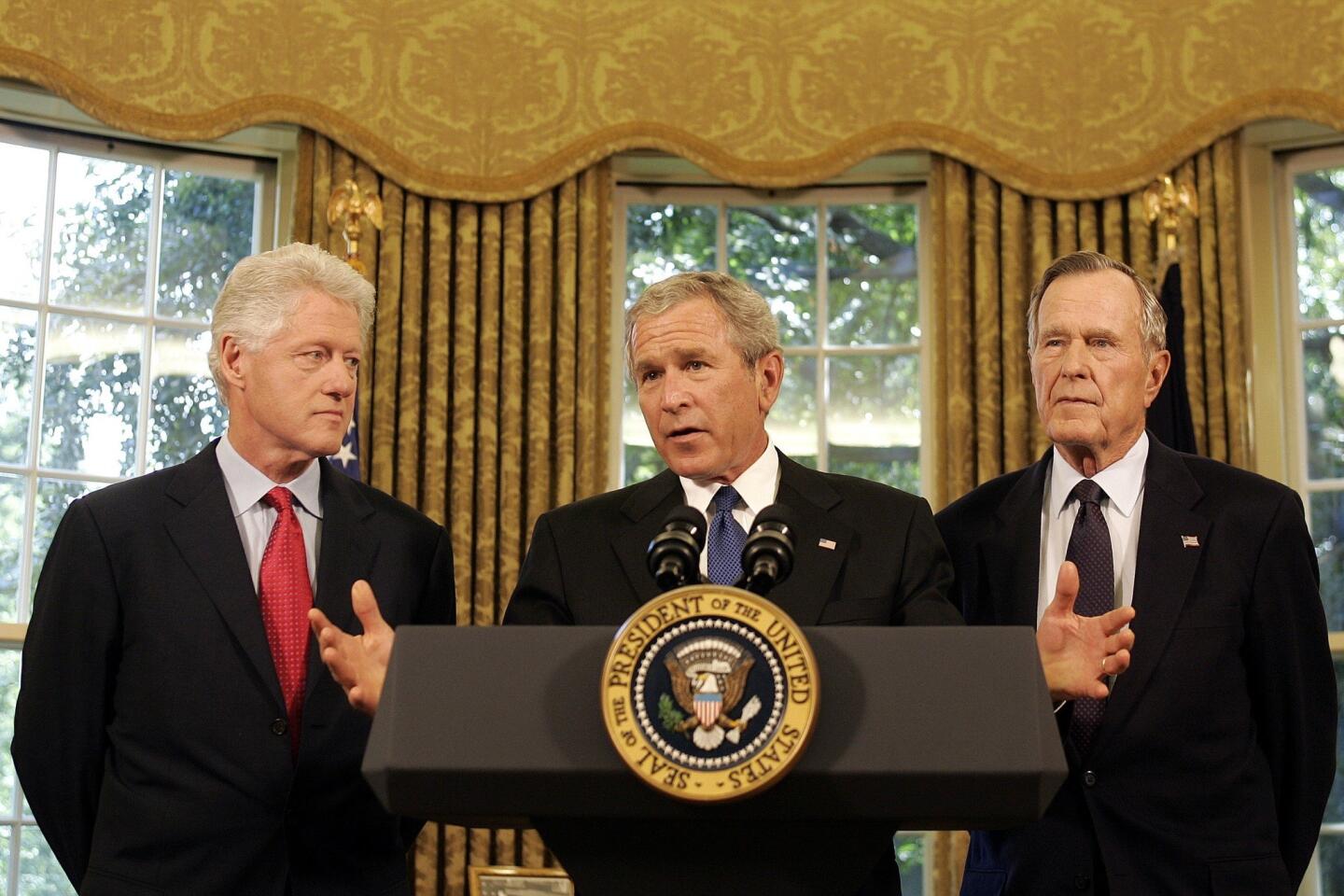

That legacy would, however, live on in part through his son George W. Bush, who in 2000 would be elected president and go on to win the second term that had eluded his father. The son’s own trials — and key decisions in which he departed from his father’s course — resulted in a more generous reappraisal of the elder Bush’s tenure.

The two were the second father and son to share the presidency, after John and John Quincy Adams. In 2016, his second son, John Ellis, known as Jeb, sought the Republican presidential nomination but was badly beaten by the eventual winner, Donald Trump.

Bush was the last in a remarkable line of eight American presidents, beginning with Dwight D. Eisenhower, whose lives had been shaped by World War II and the rivalry with the Soviets that followed. His tenure marked a dual transition — from presidencies dominated by the Cold War to a renewed focus on domestic affairs and from an America still largely run by the long-dominant white, Protestant establishment of which he was a product to a nation both more diverse and fractious.

His inability to master those transitions doomed a presidency to which he initially had appeared ideally suited by background and training.

Until his defeat in 1992 at the hands of Bill Clinton, George H.W. Bush — as he became known after his son’s rise to power — had lived what many called a charmed life, one largely dedicated to government service.

He had been a college athlete, a Navy pilot and war hero, a business success, a congressman, a diplomat, the director of the nation’s intelligence service, vice president and, finally, president.

But while he was adept at rising within the inner circles of business and government, he often seemed out of place when trying to communicate with voters. His tortured syntax and small gaffes — appearing surprised by a supermarket price scanner or glancing at his watch during a debate — fed an image of a man distant from the lives of average Americans. When recession gripped the nation in the early 1990s, his inability to connect with voters on kitchen-table issues proved his undoing.

“I couldn’t get through,” Bush would later say in an interview. “I’d say ‘Good news, the economy is recovering,’ and there would be all these people saying, ‘Bush is out of touch.’”

His pragmatic, mostly nonideological approach to government similarly marked Bush as a man from a rapidly passing era. He worked with the Democratic-controlled Congress, not only to reduce the budget deficit, but to pass historic legislation, including the Americans With Disabilities Act and a major strengthening of the Clean Air Act. But that brand of cooperation across party lines was already fading from the scene by the time he became president, and he had difficulty adapting to the new, harder-edged partisanship that came to dominate Washington.

He was innately secretive and believed in loyalty and trust above all, keeping about him a tight circle of confidants. Yet he entertained dissent in his Cabinet, recruiting advisors with disparate worldviews. His head of the Environmental Protection Agency warned of the dangers of global warming. His Housing secretary was an advocate for urban issues. At the same time, Bush nominated to the Supreme Court the man who became its most conservative member in decades, Clarence Thomas.

His post-presidential life, too, defied simple categorization. While he raked in millions giving speeches and serving on corporate boards, he also reemerged in the public eye for his humanitarian work in the wake of the tsunami that devastated southern Asia in 2004 and Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Through those efforts, he became close friends with Clinton, the Democrat who had vanquished him.

In 2011, President Obama awarded Bush the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Barbara, his wife of 73 years, died on April 17, 2018. He is survived by their sons George, Jeb, Neil and Marvin; their daughter, Dorothy; 17 grandchildren, eight great-grandchildren and two siblings, Nancy Ellis and William Bush. Another daughter, Robin, died of leukemia at age 3 in 1953.

George H.W. Bush was born in Milton, Mass., on June 12, 1924, to Prescott and Dorothy Bush and raised along with his sister and three brothers in Greenwich, Conn., one of New York’s wealthiest suburbs.

His father was a leading light of the Eastern establishment and a U.S. senator representing Connecticut from 1953 to ’63. A moderate Republican, he would ultimately oppose the red-baiting of Sen. Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s and support civil rights legislation.

Bush attended Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass., embracing the sort of “preppy” identity that would later hamper his attempts to cast himself politically as an entrepreneurial Texas oilman.

During his senior year, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, plunging the United States into war. Bush enlisted on his 18th birthday and became the youngest pilot in the Navy. His naval career nearly ended after his plane was struck over the Pacific by Japanese antiaircraft fire. His plane aflame, he delivered his bombs on target before bailing out. For his exploits, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Rotated home in time for Christmas in 1944, Bush two weeks later married Barbara Pierce, daughter of the president of the McCall’s publishing empire, whom he had met before going into the service.

No sooner was he mustered out of the Navy in September 1945 than Bush entered Yale University, where in 2½ years he earned a degree in economics and, like his father, was inducted into Skull and Bones, the oldest of the college’s exclusive secret societies. He played soccer, was captain of the baseball team and fathered a son, George Walker Bush.

That headlong rush was characteristic; throughout his life, Bush seemed constantly in motion and seldom spent time alone. While in office, his favorite forms of recreation included the speedboat he kept at his summer home in Kennebunkport, Maine, and rounds of golf played at a near sprint. In retirement, he became known for skydiving into his 90s.

After graduation, Bush turned down a job offer on Wall Street from his uncle, Herbert Walker, and decided to take his wife and child to Texas to try the oil business. By the time he reached his early 40s, oil had made Bush a millionaire.

It was then — following in his father’s path — that Bush began to carve out a new career in politics.

As he ran for elective office, Bush began a series of ideological wobbles. In his 1964 challenge to Sen. Ralph Yarborough of Texas, a liberal Democrat, Bush turned his back on his father’s moderate stands, tying himself closely to the ill-fated presidential candidacy of Republican Barry Goldwater. In addition to denouncing the 1964 Civil Rights Act as “politically inspired and destined to failure,” he opposed Medicare and the nuclear test ban treaty. He lost — buried in the presidential landslide for Lyndon B. Johnson.

By 1966, when he sought a House seat in an affluent Houston district with a moderate constituency, Bush had tacked again, shifting to the center. With a Republican tide sweeping the country, Bush won easily. Then, mindful that he had been “swamped in the black precincts,” Bush moved on civil rights, voting for the 1968 Fair Housing Act.

His stay in Congress would be brief. Asked by President Nixon to run for the Senate again in 1970, Bush lost, again.

As a salve, Nixon appointed him ambassador to the United Nations. The post kept Bush from fading out of the public scene and, importantly, provided his entree to the world of diplomacy, which would endure as his more comfortable operating environment.

Nixon yanked him from that world quickly, however, naming him chairman of the Republican National Committee just as the Watergate scandal was brewing. True to his code of personal loyalty, Bush defended Nixon until the end. President Ford rewarded him by naming him the U.S. representative to China, but recalled him to take over the Central Intelligence Agency, then under assault from Congress for improprieties around the globe.

By the time Bush left the agency in 1977, he already had the next step on the ladder in mind.

“I mean, like, hasn’t everybody thought about becoming president for years?” he would later tell a reporter for the New Yorker magazine.

His stint as party chairman had won Bush a network of contacts, held together in part by frequent, handwritten notes that he wrote for myriad occasions. By the fall of 1979, Bush was tapping them, along with his relentless energy and gregariousness, bounding from one plane and key primary state to another.

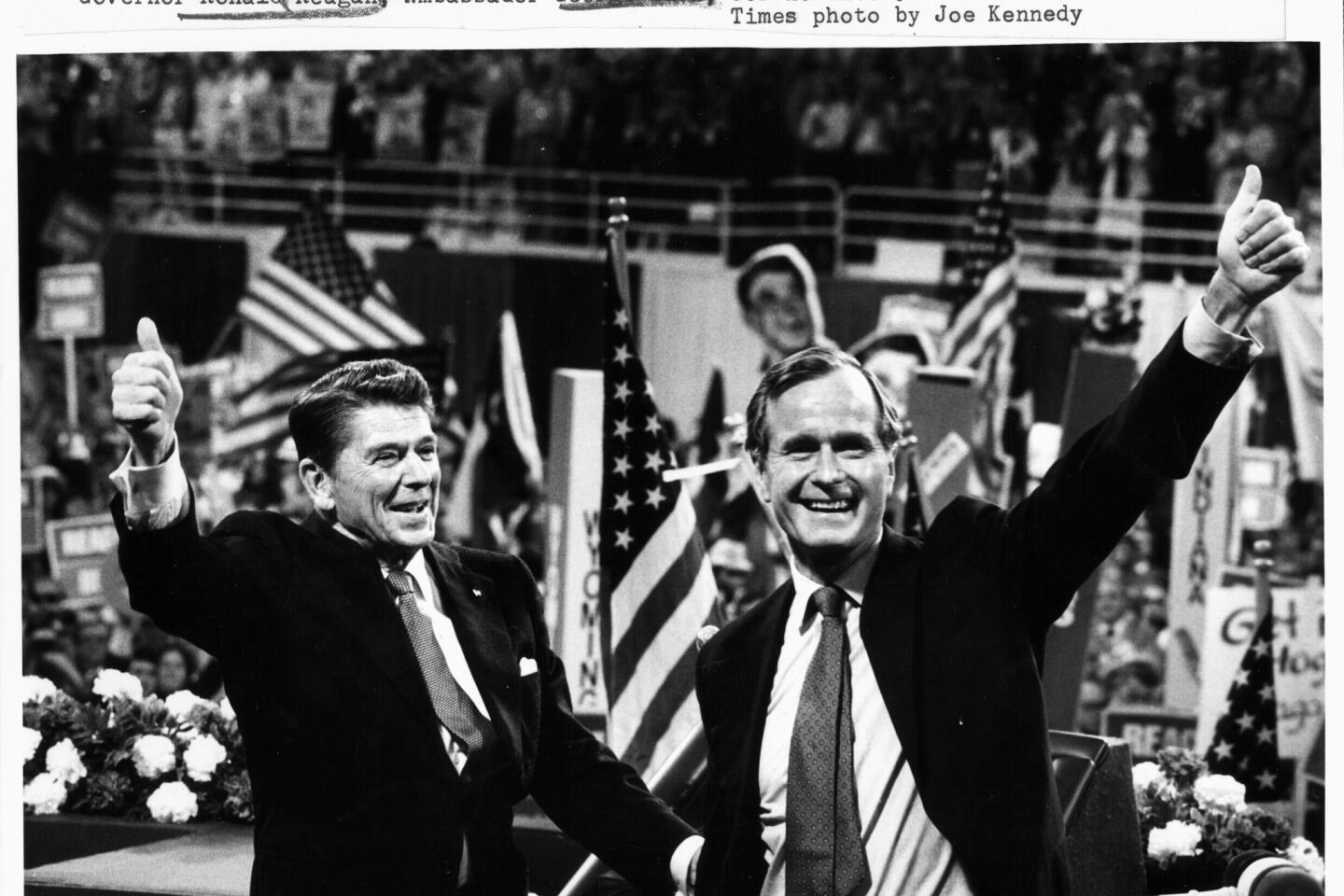

In the Iowa caucuses, the first official contest of the 1980 campaign, he scored an upset over the overwhelming favorite, Ronald Reagan. In a few weeks, however, Reagan recovered and defeated Bush decisively in the New Hampshire primary.

Bush’s problem, his staff later conceded, was that — while vaulting from obscurity to celebrity — he never gave the voters a good reason to support him.

“We established the George Who, but we never established the George What,” said his campaign manager, James A. Baker III. That problem would persist through the rest of Bush’s political career.

Bush’s candidacy was memorable chiefly for his description of the Reagan campaign’s supply-side economic proposals. “Voodoo economics,” he called it. He uttered the phrase only once, but he never heard the end of it. Democrats made it a rallying cry against Reagan for eight years.

By May, Bush had dropped out of the race. But he had made enough of an impression for Reagan, despite lingering anger over the “voodoo” remark, to select him as his running mate. To conform to Reagan’s positions, Bush dropped his opposition to a constitutional ban on abortion and his support for the Equal Rights Amendment.

In time, Bush’s unpretentiousness and quiet competence won over many of the Reagan cadre, who had doubted his adherence to the conservative cause. As Bush entered his second term as vice president and as his anticipated candidacy for the presidency drew closer, pressure increased for him to establish his own positions. Bush resisted.

His determination to subordinate himself, combined with mannerisms that sometimes seemed effusive and contrived, led Bush’s critics to deride him as a wimp and an aging preppy. Cartoonist Garry Trudeau once depicted the vice president as having “put his manhood in a blind trust,” and conservative columnist George Will, noting Bush’s efforts to win the favor of conservative groups, likened him to “a lap dog.”

As the 1988 presidential election approached, a new obstacle to Bush’s ambitions rose in the form of the Iran-Contra scandal and suspicion about his possible role. Though it required him to confess being “not in the loop,” the vice president repeatedly denied any knowledge of the deal to trade arms to gain the release of hostages held by Iran, and his candidacy weathered the storm.

Bush arrived at the GOP convention a perceived underdog to the Democratic Party candidate, Massachusetts Gov. Michael S. Dukakis. And most political professionals believed that he did not help his cause by choosing untested Indiana Sen. Dan Quayle as his running mate.

With the odds against him once again, Bush turned his acceptance address into the speech of his life, finally putting the wimp image to rest with a graceful display of self-deprecating humor.

“I’ll try to be fair to the other side,” he joshed. “I’ll try to hold my charisma in check.”

The speech, by contrast to the aggressive acquisitiveness that characterized the Reagan era, sounded the theme of compassion. In its most memorable phrase, Bush called for “a kinder and gentler nation.”

There was little kinder or gentler about the campaign against Dukakis that followed. Besides the standard campaign ploys — Bush branding Dukakis as a big spender and building support with the oft-repeated phrase: “Read my lips, no new taxes” — the vice president and his surrogates, led by the campaign’s strategist, Lee Atwater, attacked Dukakis for defending Massachusetts’ prisoner furlough law, under which a convicted murderer named Willie Horton, who was black, had been released and then committed another brutal crime. This caused some to accuse Bush of appealing to racism.

Bush also found it difficult to articulate what he wanted to accomplish as president — “the vision thing,” as he once famously called it. Still, he carried 40 states and 54% of the popular vote.

In the fall of 1989, barely a year after his election, the Berlin Wall fell and the pillars of the exhausted Soviet Union began to crumble. Reagan received the lion’s share of the credit for what Americans perceived as their victory after four decades of Cold War. But Bush and Baker, by then his secretary of State, deftly managed the transition to what Bush dubbed a “new world order,” and the president was able to ride a surge of hope and optimism even as critics complained that he was slow to react to the convulsive changes.

Then, in the summer and fall of 1990, Bush made two momentous decisions — one foreign, one domestic — that came to define his term in office.

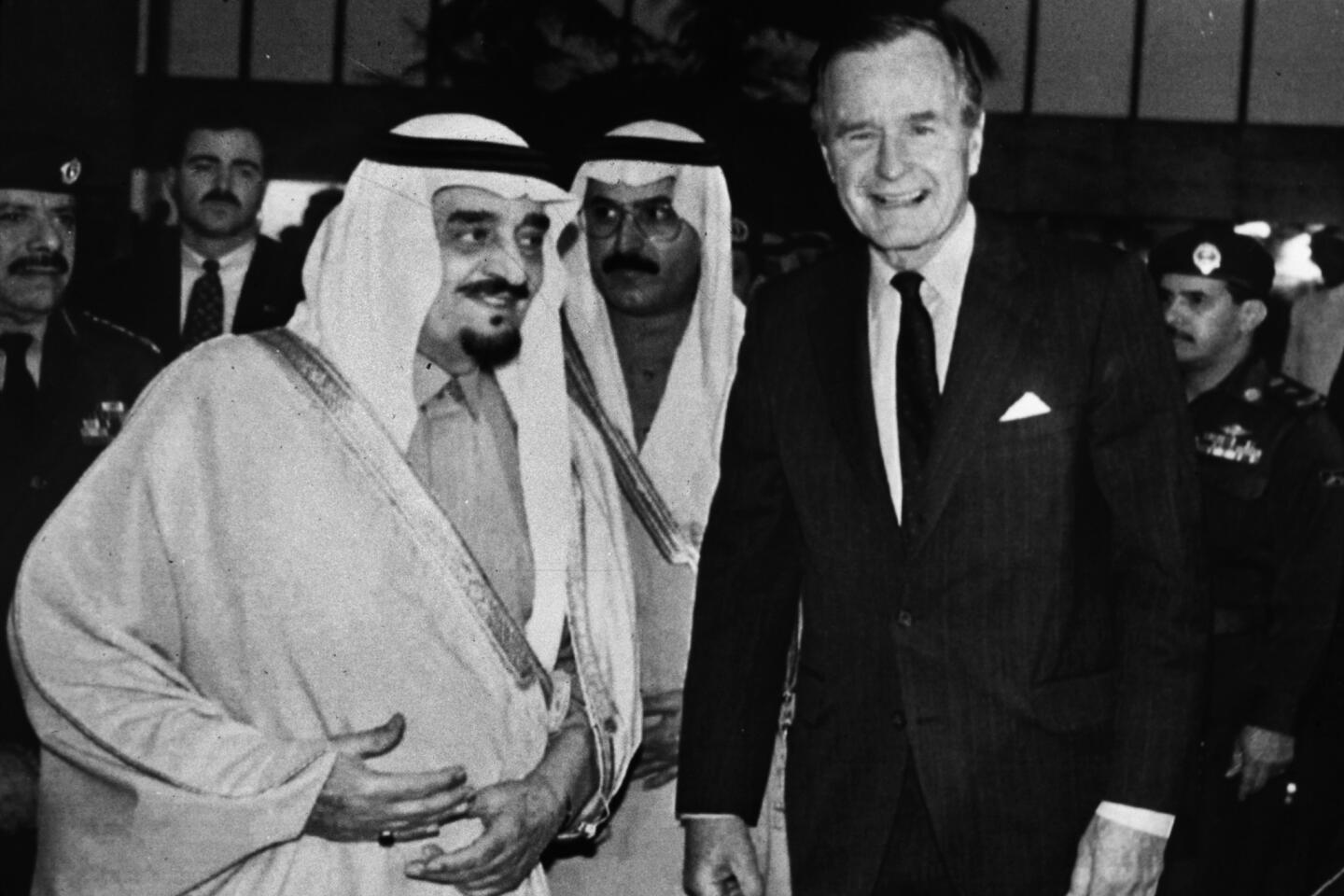

On Aug. 2, 1990, Iraq’s dictator, Saddam Hussein, sent his army across the border to quickly overrun his country’s tiny but oil-rich neighbor Kuwait. Within weeks, Bush had set in motion a massive U.S. military buildup, the largest since the Vietnam War. With minimal debate or explanation, he made the reversal of Iraq’s aggression the central purpose of his presidency.

While Bush left military logistics to the Pentagon, he personally undertook the diplomatic mobilization. Bush was masterly in this realm, where he could draw on a lifetime of personal contacts and operate behind the scenes one-on-one without needing to explain his actions in terms of his beliefs.

Later he would credit a suggestion from an old friend, Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, with helping him prepare for the crisis.

“You ought to get on the phone once in a while when there’s no problem,” Mubarak told him. “You’d be surprised what a phone call from the president of the United States would mean to another leader in the world anywhere — some small country.”

Bush had seized on the idea in the early days of his presidency, and when the time came to respond to the Persian Gulf crisis, the groundwork for swift communication had been well prepared. Bush succeeded in orchestrating, through the United Nations Security Council, a worldwide embargo against Iraq, along with authorization for a multinational military force based in Saudi Arabia.

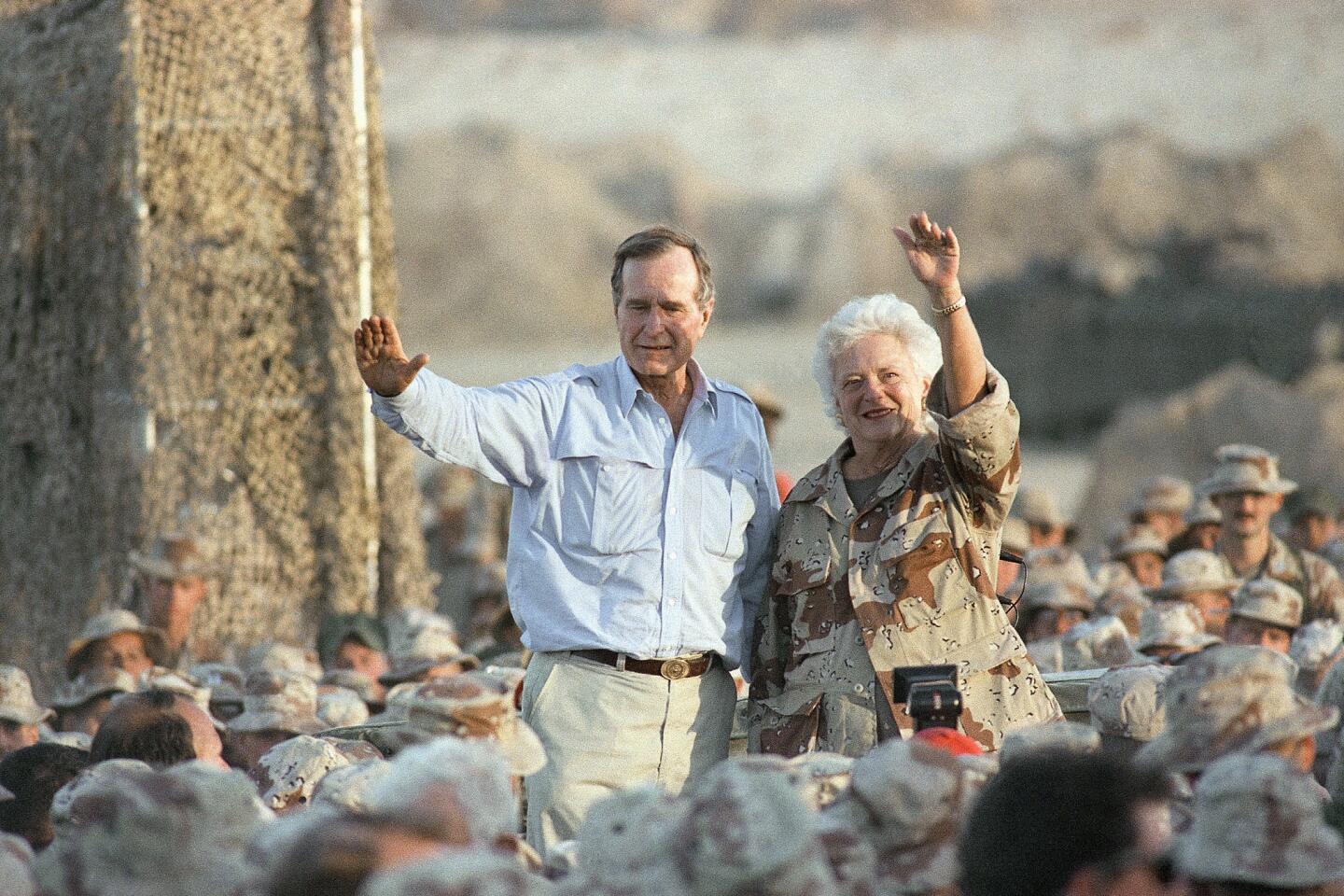

In January 1991, when the military buildup was complete, the president won congressional authorization to use force to drive the Iraqis out of Kuwait. After a massive air bombardment, a U.S.-led coalition of forces launched a ground offensive that achieved victory within 100 hours.

For Americans, grateful that their casualties totaled fewer than 500, it was a time for national rejoicing, and for Bush, it was a moment of personal triumph — even as some questioned whether he had erred by leaving Hussein in power in Baghdad.

Presidential historian Robert Dallek said that in assessing the elder Bush’s presidency in light of the later Iraq war prosecuted by George W. Bush, the father “looks better for not plunging into Iraq — it gives him a greater claim to statesmanship because he foresaw the dangers of getting into that country — he stopped at the border.”

Even as Bush orchestrated the Gulf War alliance, he was wrestling with Congress over how to handle the large budget deficits he had inherited from Reagan.

Democrats insisted that they would accept the spending cuts Bush sought only if he agreed to higher taxes. Bush’s budget director, Richard Darman, and some congressional Republicans urged the president to accept a deal. Others, led by the House’s third-ranking Republican, an ambitious conservative named Newt Gingrich, opposed the idea.

Late in 1990, Bush accepted a compromise — breaking his “no new taxes” vow. The move helped tame the deficit, setting the stage for the surpluses achieved by Clinton at the end of the decade. But it set off a revolt by Gingrich and his allies that weakened Bush within the party and soon sapped his political strength.

Then, in 1991, Bush’s nomination of Thomas to the Supreme Court, and the accompanying sexual harassment allegations, which turned his confirmation hearing into national theater, further boosted partisan animosities.

The final blow came from a short, but sharp, recession that took hold in 1990 and raised unemployment during the rest of Bush’s presidency.

In an election about change and new ideas, Bush seemed to have little to offer. The “vision thing” again hampered his efforts to outline what a second term would look like.

As the election year moved forward, the attacks in GOP primaries from Pat Buchanan, the conservative commentator, gave way to a far-more powerful danger, a third-party bid by a billionaire Texan, Ross Perot, who attracted many disaffected Republicans with his populist appeals.

At the same time, the Democrats nominated Clinton, a man who was as oratorically skilled as Bush seemed tongue-tied and energetically youthful at a time when the incumbent often seemed tired and out of sync with a rapidly changing country.

In a moment that to many crystallized the campaign, a young woman in the audience for one of the fall’s presidential debates asked Bush and Clinton how the national debt had affected their lives. Bush seemed nonplussed and unable to frame an answer. Clinton exuded empathy as he asked the woman about the challenges the economy posed for her family. The embattled president never recovered.

At the end, Bush received 38% of the popular vote, a shocking outcome 21 months after the swift and nearly bloodless liberation of Kuwait had made many view his reelection as inevitable. No incumbent had done so badly since William Howard Taft in 1912.

After leaving Washington and the presidency, Bush and the former first lady retired to Houston. He wrote his memoirs and traveled — and supported the political aspirations of his sons George and Jeb, the latter of whom served as governor of Florida from 1999 to 2007.

In a letter he wrote to the two sons in 1998, when both were running for governor of their states, which he later released in a book of his writings, Bush expressed resentment of the “far right,” which, he said, “will continue to accuse me of ‘Betraying the Reagan Revolution’ — something Ronald Reagan would never do.” And he counseled them to ignore stories that portrayed him as a president “who had no vision and who was but a place holder in the broader scheme of things.”

I am content with how historians will judge my administration.... I hope and think they will say we helped change the world in a positive sense.

— George H.W. Bush

“I am content with how historians will judge my administration — even on the economy. I hope and think they will say we helped change the world in a positive sense,” he wrote. “So read my lips — no more worrying.”

After George W. Bush’s election to the White House, he did not solicit his father’s expertise on foreign policy and national security — and the father didn’t offer any.

The son did call on Bush to team up with Clinton to raise money to aid the victims of the 2004 Asian tsunami — and Bush made several trips to the region.

“Here was a young child, life shattered, mother drowned in front of her, sitting on a mud floor. It’s terribly moving,” Bush said in an interview. Bush and Clinton also worked together to help the Gulf Coast recover from the devastation of Hurricane Katrina.

But on the larger issues, Bush kept his views to himself.

“A president has got plenty of advisors, but what a president never has is someone who gave him unconditional love,” the younger Bush said in an interview at the close of his second term. “And therefore when I talked to my dad, I was more interested in the father-son relationship.”

In the same interview, the elder Bush said he had been “determined to stay out of the way.”

Only after he reached his 80s, with George W. Bush out of office, did the elder Bush confide to his biographer, John Meacham, that he thought his son’s occasional “hot rhetoric” and the “iron-ass” influence of his vice president, Dick Cheney, had created an image of inflexibility for the 43rd president’s administration.

Despite his family’s political accomplishments, Bush disliked the idea that his family was viewed as a “dynasty” with a “legacy.”

“Those two words, ‘dynasty’ and ‘legacy’ — irritate me,” Bush told the New York Times during his son’s campaign for the presidency in 2000. “We don’t feel entitled to anything.”

.

Oliphant is a former Times staff writer. Former Times staff writers Robert Shogan and Claudia Luther contributed to this report.

Tweeted tributes to a former president from Trump, Obama, DeGeneres and more »

‘Read my lips,’ ‘a thousand points of light’ and broccoli: memorable lines from the 41st president »

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.