James Watt, sharp-tongued and pro-development Interior secretary under Reagan, dies at 85

CHEYENNE, Wyo. — James Watt, the Reagan administration’s sharp-tongued, pro-development Interior secretary who was beloved by conservatives but ran afoul of environmentalists, Beach Boys fans and eventually the president, has died. He was 85.

Watt died in Arizona on May 27, his son Eric Watt said in a statement Thursday.

In an administration divided between so-called pragmatists and hard-liners, few stood as far to the right at the time as Watt, who once labeled the environmental movement as “preservation vs. people” and the general public as a clash between “liberals and Americans.”

In that sense, Watt foreshadowed combative Interior secretaries like Ryan Zinke and David Bernhardt, who, like Watt, aggressively pushed to grant oil, gas and coal leases on public land, increase offshore drilling and limit expansion of national parks and monuments.

“While no one’s death should be celebrated, he was the worst of MAGA before it was invented,” tweeted David Donger of the environmental group Natural Resources Defense Council, referring to former President Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan.

Watt and his supporters saw him as an upholder of President Reagan’s core conservative values, but opponents were alarmed by his policies and offended by his comments. In 1981, shortly after he was appointed, the Sierra Club collected more than 1 million signatures seeking Watt’s ouster and criticized such actions as clear-cutting federal lands in the Pacific Northwest, weakening environmental regulations for strip mining and hampering efforts to curtail air pollution in California’s Yosemite Valley.

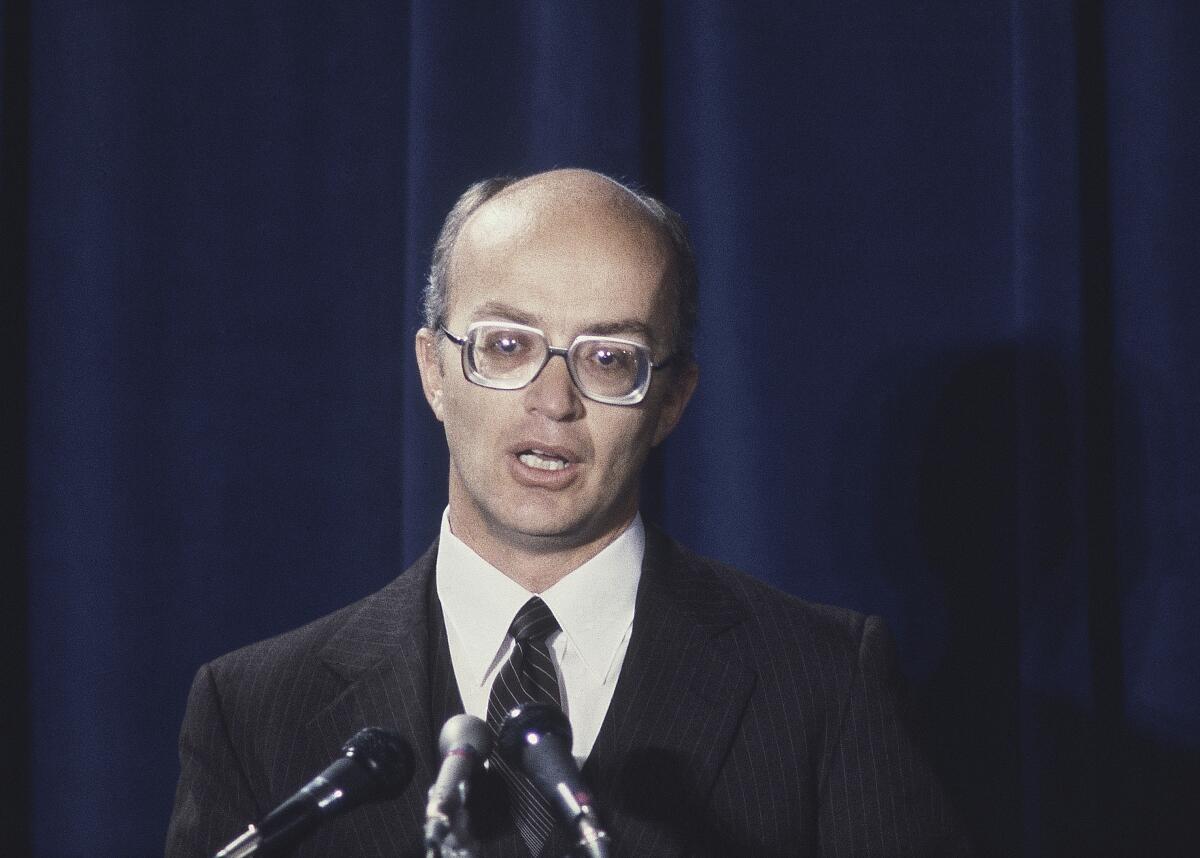

With his bald head and thick glasses, he became the rare Interior secretary recognizable to the general public, for reasons beyond the environment. He characterized members of a coal advisory panel using derogatory language and in 1983 tried to ban music from Fourth of July festivities on the National Mall, saying it attracted the “wrong element.”

The Beach Boys had been recent mall headliners, and their fans included President Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan. With Watt’s statement facing widespread mockery, the Reagans invited the Beach Boys for a special White House visit. Watt, meanwhile, was summoned to receive a plaster model of a foot with a hole in it.

Starting with ‘squaw,’ U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland intends to have it and other derogatory place names removed from federal government use.

In his 1985 book “The Courage of a Conservative,” Watt wrote that the controversy “actually arose because I was a conservative. Members of a liberal press saw an opportunity to create a controversy by censoring the facts and avoiding the real issues.” He said the initial stories about the rock music ban “only mentioned that the Beach Boys had performed in the past. Yet before we knew what was happening, banner headlines proclaimed that I had banned the Beach Boys. I was astonished.”

Cutting regulations was his primary mission. Between the time he was confirmed as Interior secretary in 1981 until he resigned under pressure in 1983, Watt implemented an offshore leasing program that offered virtually the entire U.S. coastline for oil and gas drilling and held the largest coal lease sale in history, auctioning off 1.1 billion tons of coal in the Powder River Basin of Montana and Wyoming.

Watt tripled the amount of onshore land being leased for oil and gas exploration and doubled the acreage leased for geothermal resources.

Watt did spend $1 billion to restore and improve national parks and added 2,800 square miles to the nation’s wilderness system. And his efforts to exploit natural resources made America stronger, he wrote to Reagan in October 1983.

“Our excellent record for managing the natural resources of this land is unequaled — because we put people in the environmental equation,” Watt wrote.

But eight days after writing to the president, he rode horseback into a cow pasture down the road from Reagan’s California ranch to announce his resignation. He was succeeded by a longtime Reagan aide, William Clark.

“I had outworn my usefulness,” Watt said of his decision, adding that others “wouldn’t get off my case” about his insulting coal advisory panel comment.

Watt was born Jan. 31, 1938, in Lusk, Wyo., and his family later moved to Wheatland, Wyo., where his father practiced law. He attended the University of Wyoming, graduating in 1960 and obtaining a law degree two years later.

U.S. to spend an additional $103 million for wildfire risk reduction and burned-area rehabilitation, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland says.

In 1962, Watt became a personal assistant to former Gov. Milward L. Simpson, and he went to Washington after Simpson was elected to the U.S. Senate later that year. In 1966-69, he helped develop policies on such issues as pollution, mining, public lands and energy for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, then in early 1969 he joined the Nixon administration as an Interior Department undersecretary.

In 1975, President Ford appointed him to the Federal Power Commission.

While Jimmy Carter was president, Watt worked in the private sector as president and chief legal officer of the pro-development Mountain States Legal Foundation in Denver.

He did consulting work after leaving the Reagan administration, at one point turning heads when he agreed to represent Native American tribes in oil operations and hotel developments after previously labeling Indigenous reservations “the failure of socialism.” He also accepted six-figure consulting fees to represent developers of a federally subsidized housing project.

He moved back to Wyoming in 1986 and set up a law office in Jackson, taught at his alma mater and served as a legal consultant and speaker.

But his consulting work involving federal housing money came under scrutiny in the late 1980s when an investigation was launched into corruption in the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

In 1996, he pleaded guilty to a single misdemeanor for withholding documents from a grand jury investigating HUD. He was fined $5,000, put on five years’ probation and ordered to perform community service. He said he had “made a serious mistake” and hoped to “get on with a constructive role in society.”

Over the years, Watt expressed fears that unless they were stopped, radical environmental movements like Earth First! would persuade the “cowards of Congress” to ban all hunting, eliminate all logging and livestock grazing on public lands and further jeopardize the minerals industries.

He lived in his later years in Wickenburg, Ariz., with his wife, Leilani.

Associated Press writer Matthew Daly in Washington, D.C., contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.