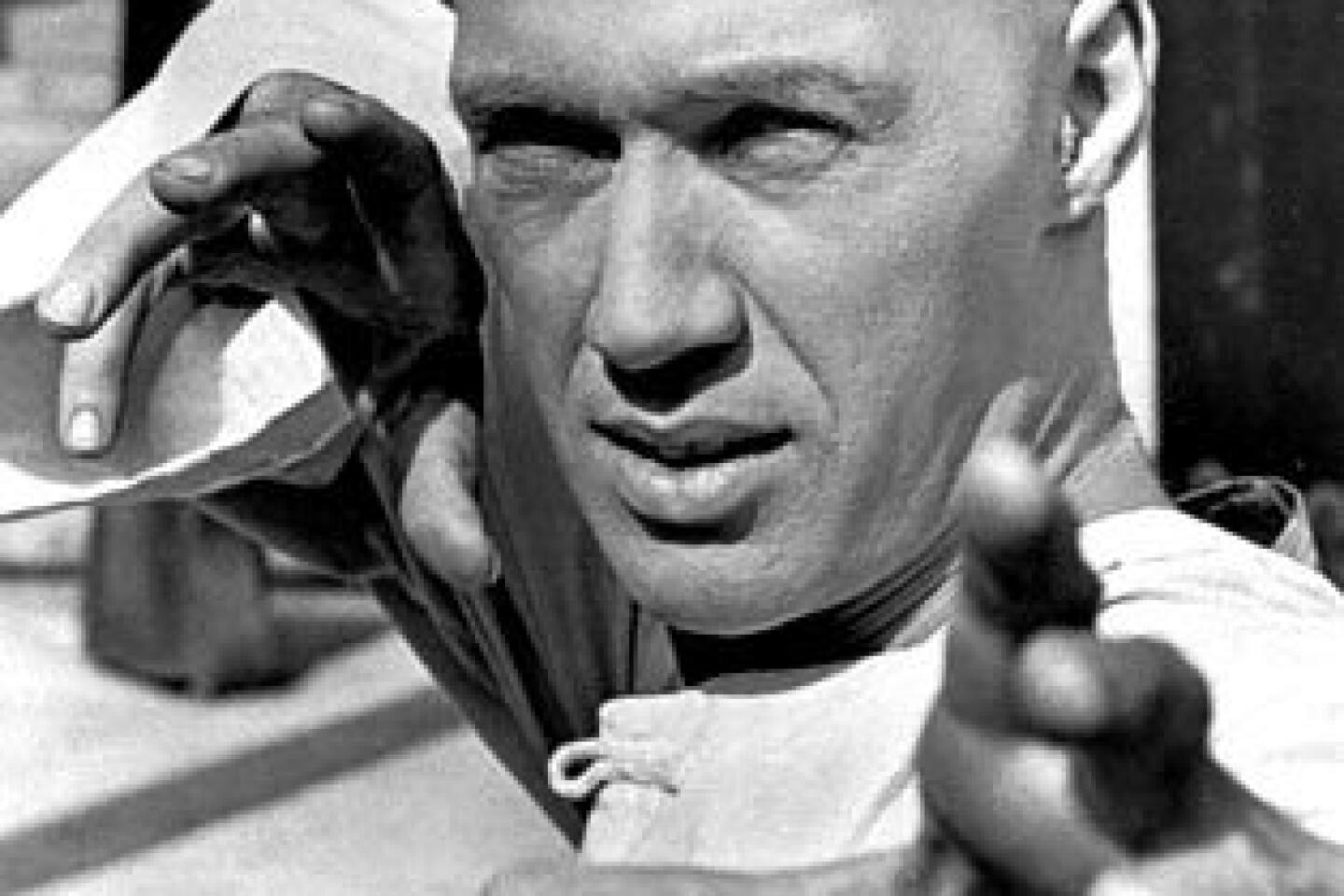

David Carradine dies at 72; star of ‘Kung Fu’

David Carradine, who became a TV icon in the early 1970s starring as an enigmatic Buddhist monk with a flair for martial arts in “Kung Fu” and more recently played the head of a group of assassins in the “Kill Bill” movies, has been found dead in Bangkok, Thailand. He was 72.

Carradine was found hanged in his luxury hotel suite Thursday, the Thai newspaper the Nation reported on its website, citing unidentified police sources.

The actor, who was in Bangkok to shoot a movie, could not be contacted after he failed to appear for a meal with the film crew on Wednesday, the newspaper said.

His body was found by a hotel maid Thursday morning.

A Thai police officer who is investigating the actor’s death told the Associated Press that Carradine’s naked body was found hanging in the closet of his suite.

The Thai newspaper reported that a preliminary police investigation found that Carradine had hanged himself with a curtain cord and that there was no sign of foul play.

An autopsy is expected to be performed today.

Chuck Binder, who was Carradine’s manager, cautioned against prematurely concluding the actor committed suicide and emphasized the death was being investigated by police.

“I know David pretty well,” Binder said. “I do not believe he is a candidate for suicide. He had a family. He had a life. He was happy. This movie in Bangkok was going great. He was starting three more films. He was in great spirits.”

In a statement to The Times, Martin Scorsese, who had known Carradine since directing him in the 1972 movie “Boxcar Bertha,” said he was “deeply saddened” by the actor’s death.

“David was a great collaborator, a uniquely talented actor, and a wonderful spirit,” he said.

The son of noted character actor John Carradine, David Carradine appeared in more than 100 films, including Ingmar Bergman’s “The Serpent’s Egg” (1977).

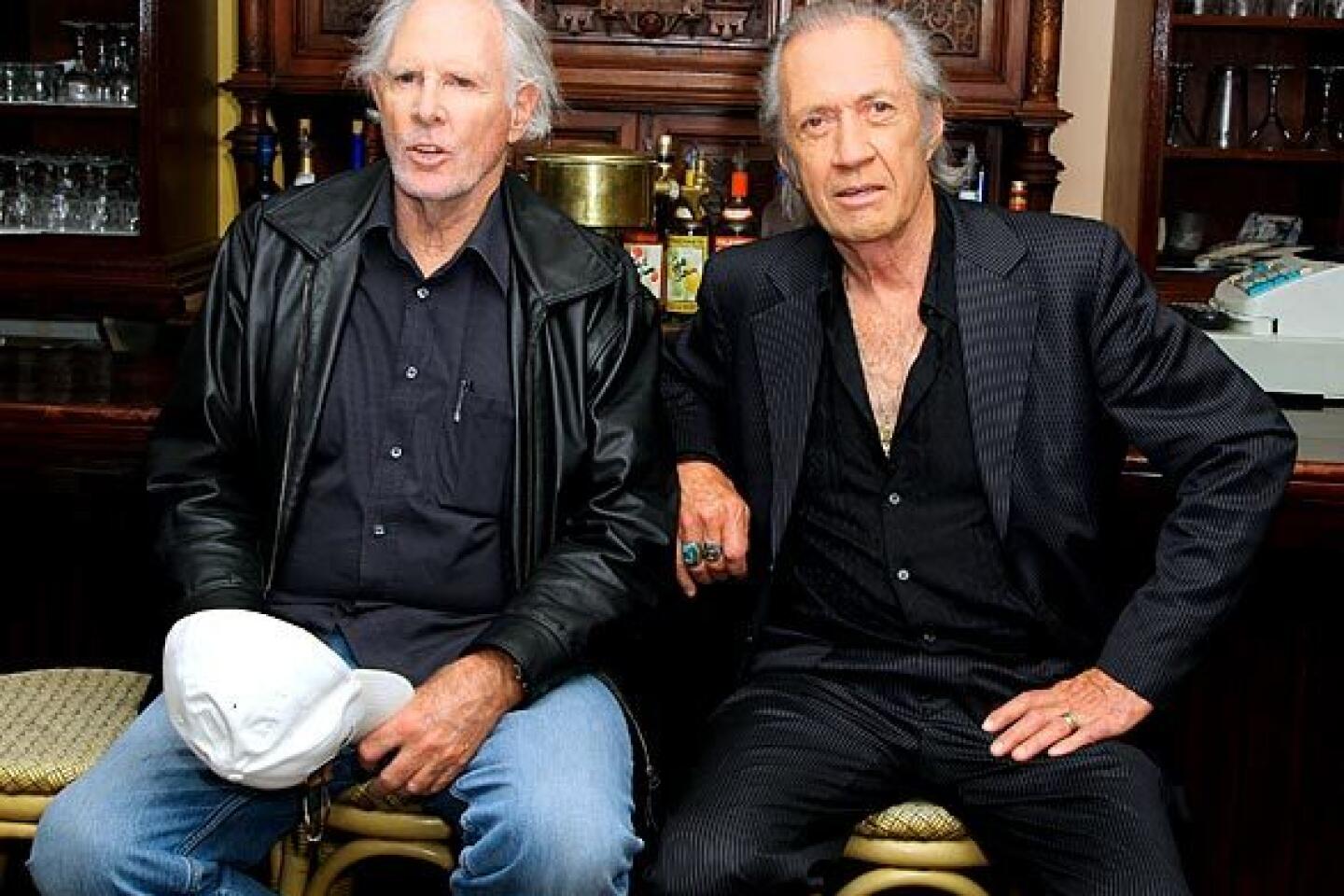

He also played folk singer Woody Guthrie in Hal Ashby’s “Bound for Glory” (1976) and appeared with his brothers Keith and Robert in the 1980 western “The Long Riders.”

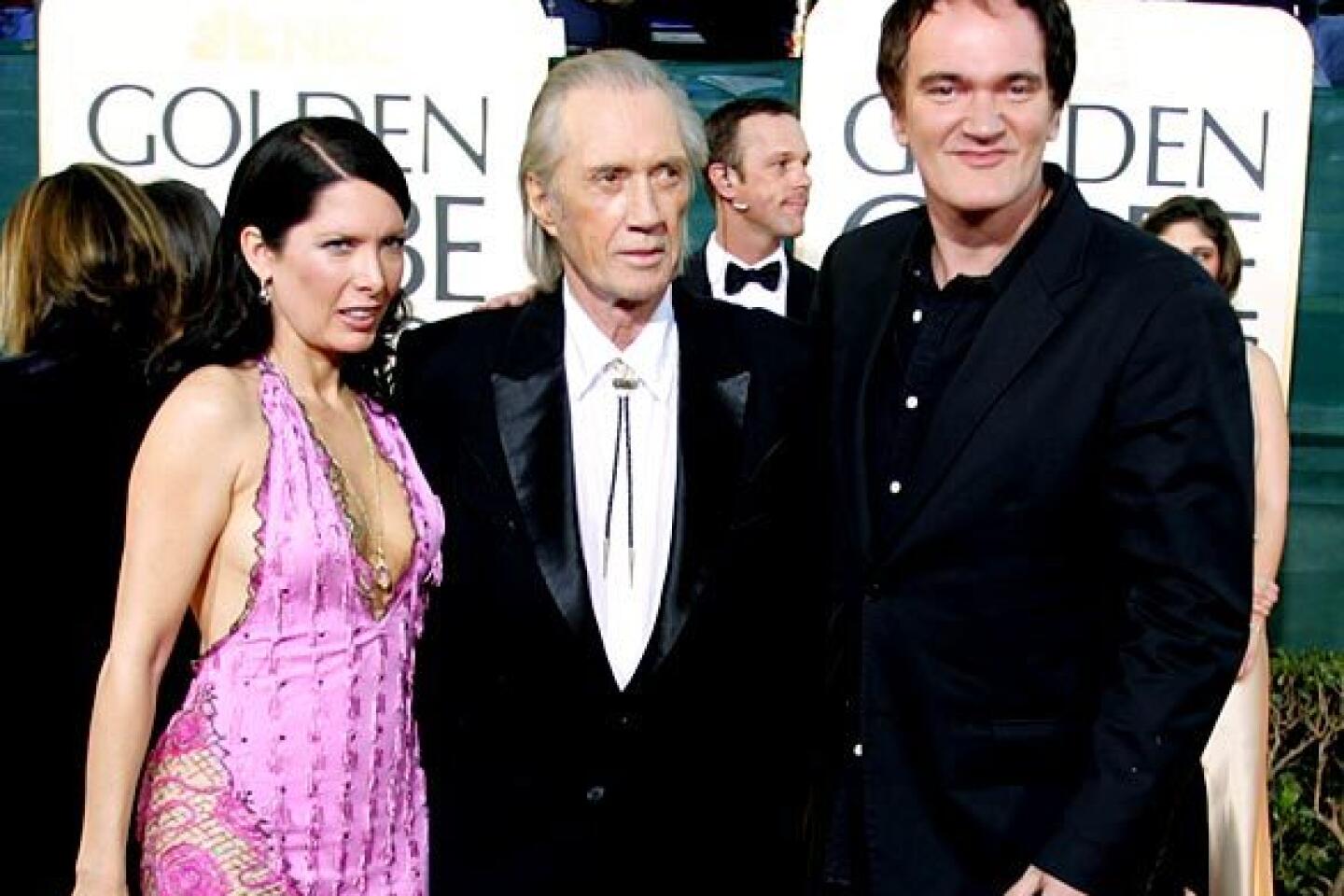

More recently, he played the title character of a samurai-trained assassin in Quentin Tarantino’s two-film “Kill Bill” saga (2003 and 2004).

Carradine, however, remained best known for “Kung Fu,” which ran on ABC from 1972 to 1975.

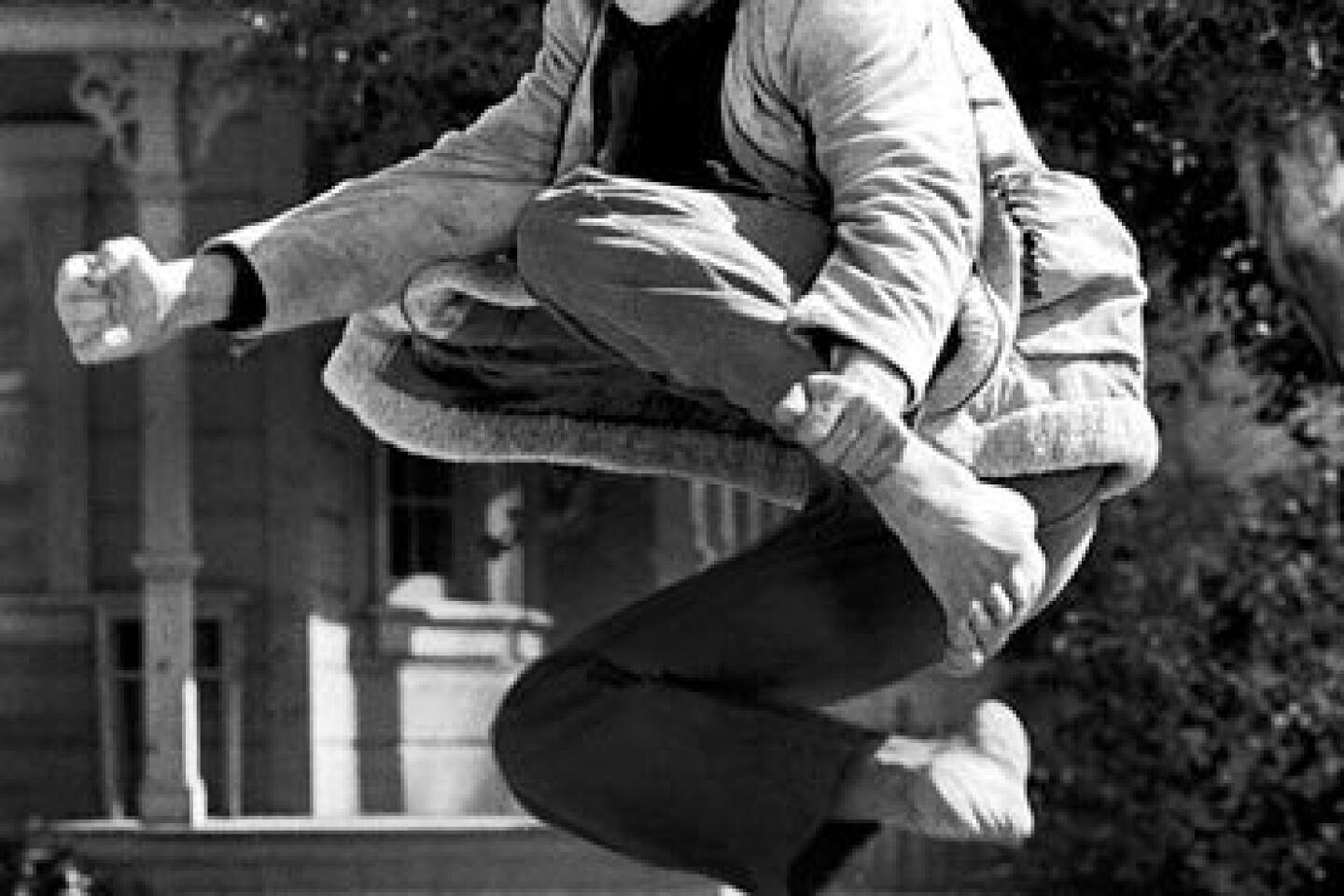

The hourlong series featured Carradine as the shaven-headed Kwai Chang Caine, the orphaned son of an American man and a Chinese woman who had been trained in a Shaolin monastery, where his blind mentor, Master Po, called his young student “Grasshopper.”

When Po is murdered by the Chinese emperor’s nephew, Caine kills the nephew. To avoid execution, he flees to the American West.

The series, for which Carradine received an Emmy nomination, is credited with helping popularize martial arts in the West.

But in his memoir “Spirit of Shaolin,” Carradine admitted that while making the series “I was a fake.”

“I knew nothing about kung fu,” he wrote. “At the time I did not understand it at all, and I was faking it all the time even though I knew the moves. I am an actor. We just thought we had a good story.”

Carradine, however, later studied the techniques and philosophy of martial arts and made a number of instructional videos.

He returned to play the grandson of his original “Kung Fu” series character in the 1993-1996 syndicated series “Kung Fu: The Legend Continues.”

A self-described Hollywood outsider, Carradine early on had a reputation for what an Associated Press writer in 2004 described as “a quick-to-anger actor and hard-drinking partier.” But he reportedly gave up drinking in 1996 and candidly discussed his past drinking and drug use, primarily involving what Carradine described as “a lot of psychotropic drugs.”

Carradine, who appeared in the 1985 TV mini-series “North and South,” appeared mostly in small independent films over the last few decades.

“He’s been undervalued as an actor,” Stacy Keach, a longtime friend who co-starred with Carradine in “The Long Riders” and “Gray Lady Down,” told the Star-Ledger of Newark, N.J., in 2004. “David is a real practitioner in details, nuance, which is where great art lives. He has a reservoir of imagination and a totally unique point of view about everything.”

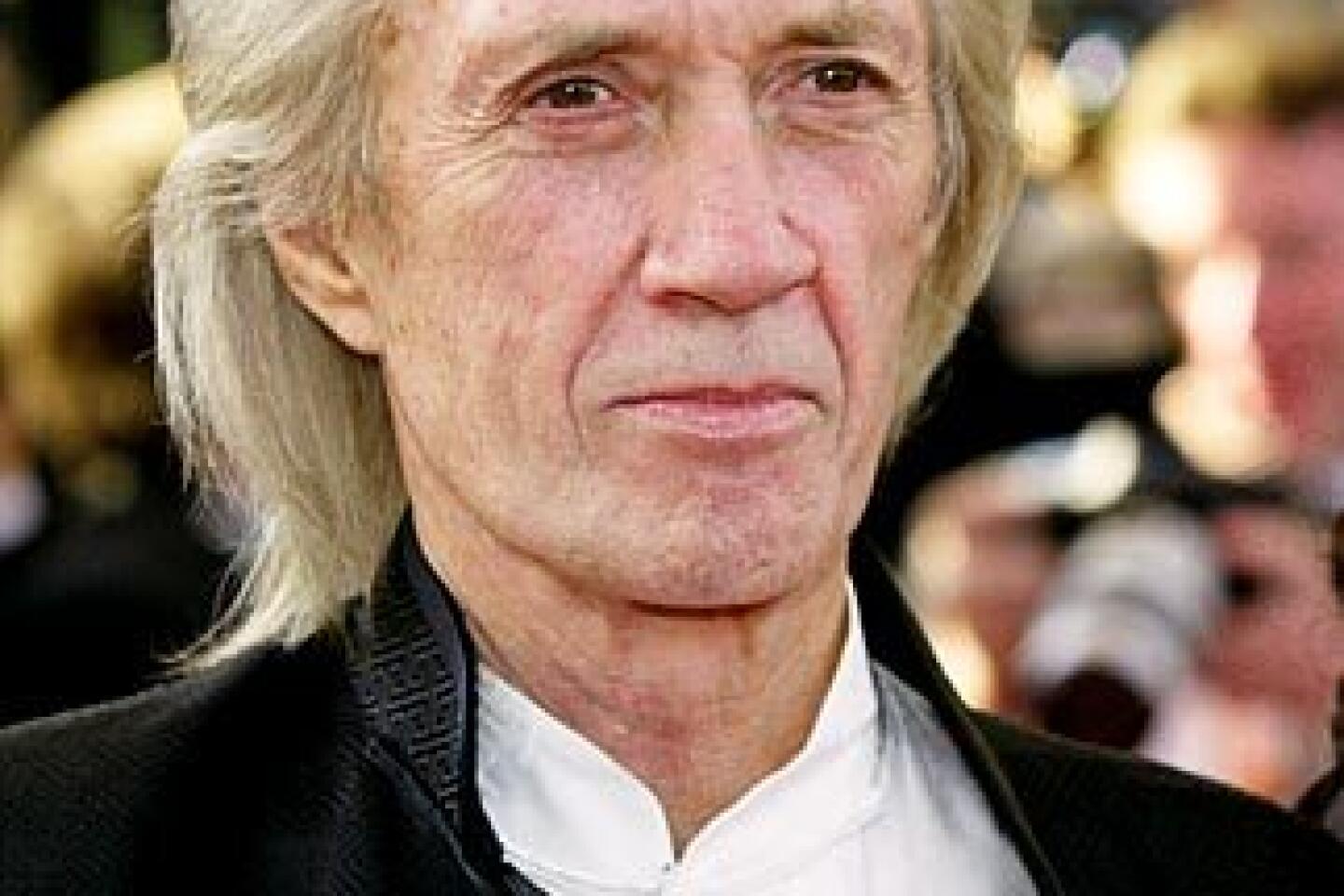

Carradine returned to the limelight several years ago when Tarantino cast him in “Kill Bill,” with Uma Thurman.

“Playing in ‘Kill Bill’ helped,” Carradine told the Austin American-Statesman in 2005. “Up until then everyone was saying ‘Grasshopper.’ Now everyone says ‘Bill.’ ”

Tarantino, who is known for resurrecting the careers of veteran actors, reportedly tailored the role of Bill for Carradine.

“David Carradine -- Caine! -- I grew up with this guy,” Tarantino said before the release of “Kill Bill: Vol. 1” in 2003. “He was so cool as Caine. He was always the cool one. He’s the coolest in ‘Kill Bill.’ He is Bill.”

His performance in “Kill Bill: Vol. 2” earned Carradine a Golden Globe nomination as best supporting actor.

In a 2004 interview with the Baltimore Sun while promoting “Kill Bill: Vol. 2,” Carradine said: “I’ve never been satisfied about anything in my entire life. I’m on Social Security, I’ve got my pension, and the fact remains that I’m still trying to make a name for myself.”

Born in Hollywood on Dec. 8, 1936, Carradine studied music theory and composition at San Francisco State. He developed an interest in acting while writing music for drama department revues and joined a Shakespearean repertory company.

Carradine, who had a two-year stint in the Army in the early ‘60s, appeared on Broadway in the mid-’60s in “The Deputy” and “The Royal Hunt of the Sun.”

Around the same time, he also made guest appearances on TV series such as “Wagon Train” and “The Virginian” and starred in the short-lived 1966 western series “Shane.”

Carradine’s survivors include his wife, Anne Bierman Carradine, and children. A complete list of surviving family members was not immediately available.

Times staff writer Valerie J. Nelson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.