Judy Garland, who paid a tragic price for the life of the show-business superstar, died in London Sunday. She was 47.

It was the quiet end to a stormy career. Although she had tried suicide countless times, Scotland Yard said there was no indication she had taken her own life.

Her fifth husband, Mickey Deans, 35, found her dead. Illness had plagued her constantly, but it was not immediately determined what caused her death. An autopsy was scheduled today.

She had suffered from hepatitis, exhaustion, kidney ailments, nervous breakdowns, near-fatal drug reactions, overweight, underweight and injuries suffered in falls.

Unhappy Love Affairs

Her previous four marriages had ended in divorce and her life was a chaos of unhappy love affairs.

Her career was a series of soaring highs and plummeting lows. She was a top box office film star of the 1940s, established all-time personal appearance records in the ‘50s and was twice nominated for Academy Awards.

Between the high points she suffered abysmal slumps. She was sued repeatedly for backing out of performances, was fired for contractual failures, and was booed offstage when she forgot the lines in her songs. In London in January an audience hurled bread, rolls and glasses at her after she kept them waiting for an hour.

“Some times I feel like I’m living in a blizzard,” she once said. “An absolute blizzard.”

But, throughout her crisis-ridden career, she refused to quit fighting. She was Hollywood’s queen of the comebacks. When her career — and, usually, her personal life — hit rock bottom, she would stage a spectacular comeback and again hit the bigtime.

“Judy has been coming back since she was invented,” a London critic once wrote. “She doesn’t give a concert, she conducts a seance.

“She evokes pity and sorrow like no other superstar.”

Her best known role was that of Dorothy, at 17, in the 1939 film “The Wizard of Oz” — in which she sang the song which became her trademark: “Over the Rainbow.”

A wistful teen-ager with a turned-up nose, brown eyes, brown hair and a rich, full voice, she became a top star in the big-star days of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s golden age.

Loses Her Youth

And, in the process, she lost her own youth.

“Judy was a child who never had any childhood,” said Ray Bolger, a costar in “Oz,” Sunday, “She was a child who never grew up.”

She made 12 films as a teen-ager and was under psychiatric treatment by the time she was 18. By the time she was 23 she had had three nervous breakdowns.

When she was 28 she slashed her throat in a suicide try. Her third husband, Sid Luft, said she attempt to kill herself 20 times in the 13 years they were married.

But she refused to stay down, despite recurring personal and professional disaster.

Bored With Herself

“I’m always being painted a more tragic figure than I am,” she said in 1962. “Actually, I get awfully bored with myself as a tragic figure.”

It was estimated that her films made more than $100 million. Most were big-budget musicals of the ‘40s, although she won critical esteem for her acting ability in later films.

Among her starring roles were “Broadway Melody of 1938,” “Babes in Arms,” “Strike Up the Band,” “Ziegfeld Girl,” “Girl Crazy,” “Meet Me in St. Louis,” the Andy Hardy films in which she starred with Mickey Rooney, “The Harvey Girls,” “Easter Parade,” and, since 1954, “A Star is Born” and “Judgment at Nuremberg,” for which she received Oscar nominations.

Her film career and her life almost ended in 1950. MGM, where she had made 30 films, fired her when she failed to report for work, and cast Betty Hutton in role in “Annie Get Your Gun.” She slashed her throat with a broken water glass, was saved, then stuffed herself to obesity.

“I went to pieces,” she recalled later. “All I wanted to do was eat and hide. I lost all my self-confidence for 10 years. I suffered agonies of stage fright. People had to literally push me onto the stage.”

But she made a smashing comeback in personal appearances. She broke all-time vaudeville records at the Palace in New York in 1951, ’56 and ’57. She sang a sadder-but-wiser “Rainbow” at Carnegie Hall which became part of what some called one of the best live recordings ever made.

Wistful Voice

In 1963 she made 26 half-hour television shows for CBS. She was last seen on national television Saturday, when a Johnny Carson interview taped in 1968 was rerun. On it she told of her youth in vaudeville, before she soared to the top — and began the long fall back down.

In later years, what had been a rich, creamy, wistful voice began to show cracks and tremors. But the feeling she put into songs like her perennial “Over the Rainbow” made up for what one critic referred to as “a tremolo which at times can suggest a fly-wheel about to tear loose.”

Nervous, fidgety, seemingly fighting for control, she would come on stage almost tentatively — and then, after a few songs, burst forth into the old Garland style that had made her a star.

Sometimes, though, she was booed off the stage when she couldn’t put a show — or herself — together. Her intermissions sometimes lasted 90 minutes. A role promised her in “Valley of the Dolls” went to Susan Hayward because she couldn’t show up in time for the shooting schedule.

“I’ve heard how ‘difficult’ it is to be with Judy Garland,” she said a few years ago, more sadly than defensively, “but do you know how difficult it is to BE Judy Garland? And for ME to live with me? I’ve had to do it — and what more unkind life can you think of than the one I’ve lived?”

1/25

Kobe Bryant, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sean Connery and more. (Los Angeles Times)

2/25

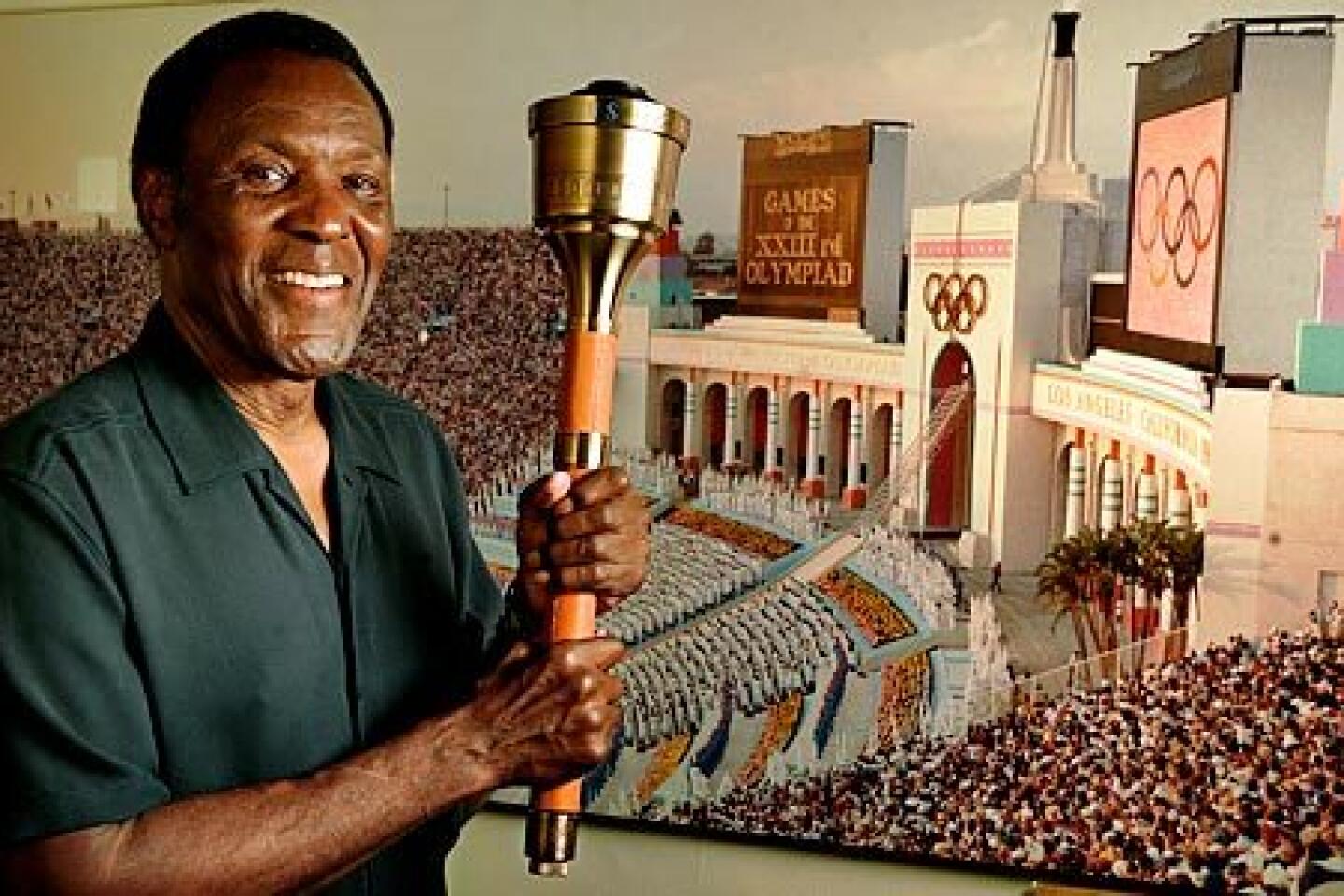

Rafer Johnson, winner of the 1960 Olympic decathlon gold medal, was a man whose legacy was interwoven with Los Angeles history, beginning with his performances as a world-class athlete at UCLA and punctuated by the night in 1968 when he helped disarm Robert F. Kennedy’s assassin at the Ambassador Hotel. Johnson lit the Olympic flame at the opening of the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles. He was 86.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times) 3/25

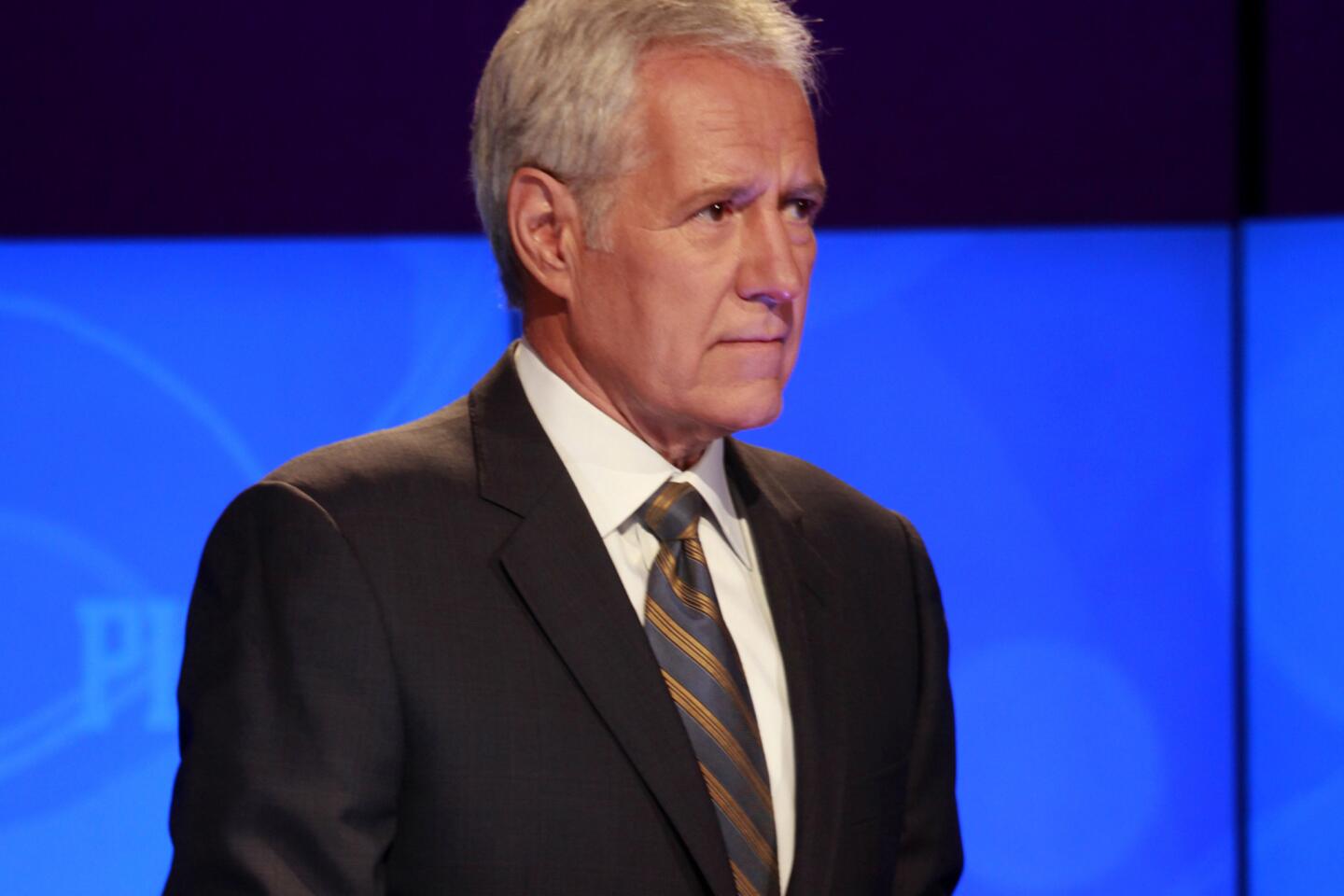

With his quick wit and easy smile,

Alex Trebek drove the game show “Jeopardy!” up the ratings charts and became a welcome television host in America’s living rooms. As the quiz show rolled through the decades, Trebek remained a comfortable fit — in a 2014 Reader’s Digest poll, Trebek ranked as the eighth-most trusted person in the United States, right behind Bill Gates and 51 spots above Oprah Winfrey. He was 80.

(Los Angeles Times) 4/25

Guitarist Eddie Van Halen’s speed and innovations along the fretboard inspired a generation of imitators as the band bearing his name rose to MTV stardom and multiplatinum sales over 10 consecutive albums. The streak made Van Halen one of the most successful bands in rock history, including two albums that reached diamond status (10 million copies sold): 1978’s debut “Van Halen” and 1984’s “1984.” He was 65.

(Wibbitz/Getty) 5/25

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg championed women’s rights — first as a trailblazing civil rights attorney who methodically chipped away at discriminatory practices, then as the second woman to serve on the Supreme Court, and finally as an unlikely pop culture icon. A feminist hero dubbed Notorious RBG, Ginsburg became the leading voice of the court’s liberal wing, best known for her stinging dissents on a bench that mostly skewed right since her 1993 appointment. She was 87.

(Kiichiro Sato / Associated Press) 6/25

Chadwick Boseman’s breakout role was playing Dodger Jackie Robinson in the 2013 sports biopic “42.” The next year, he made an electrifying lead turn as James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, in “Get on Up.” Then came the role that would change his career: As

Black Panther, the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s first Black superhero, Boseman became the face of Wakanda to millions of fans around the world and helped usher in a new and inclusive era of superhero blockbusters. He was 43.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 7/25

Sumner Redstone outmaneuvered rivals to assemble one of America’s leading entertainment companies, now called ViacomCBS, which boasts CBS, Comedy Central, MTV, Nickelodeon, BET, Showtime, the Simon & Schuster book publisher and Paramount Pictures movie studio. Unlike contemporaries Rupert Murdoch and Ted Turner, Redstone was not a visionary, but rather a hard-charging lawyer and deal maker who pursued power and wealth through the accumulation of content companies. He was 97.

(Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times) 8/25

Regis Philbin reigned for decades as the comfortable and sometimes cantankerous morning host of “Live,” first with Kathie Lee Gifford and later Kelly Ripa, above. He earned Emmy nominations by the armful, hosted New Year’s Eve specials, rode in parades, set a record for the most face-time hours on television and helped reinvigorate prime-time game shows with “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire.” He was 88.

(Charles Sykes / Associated Press) 9/25

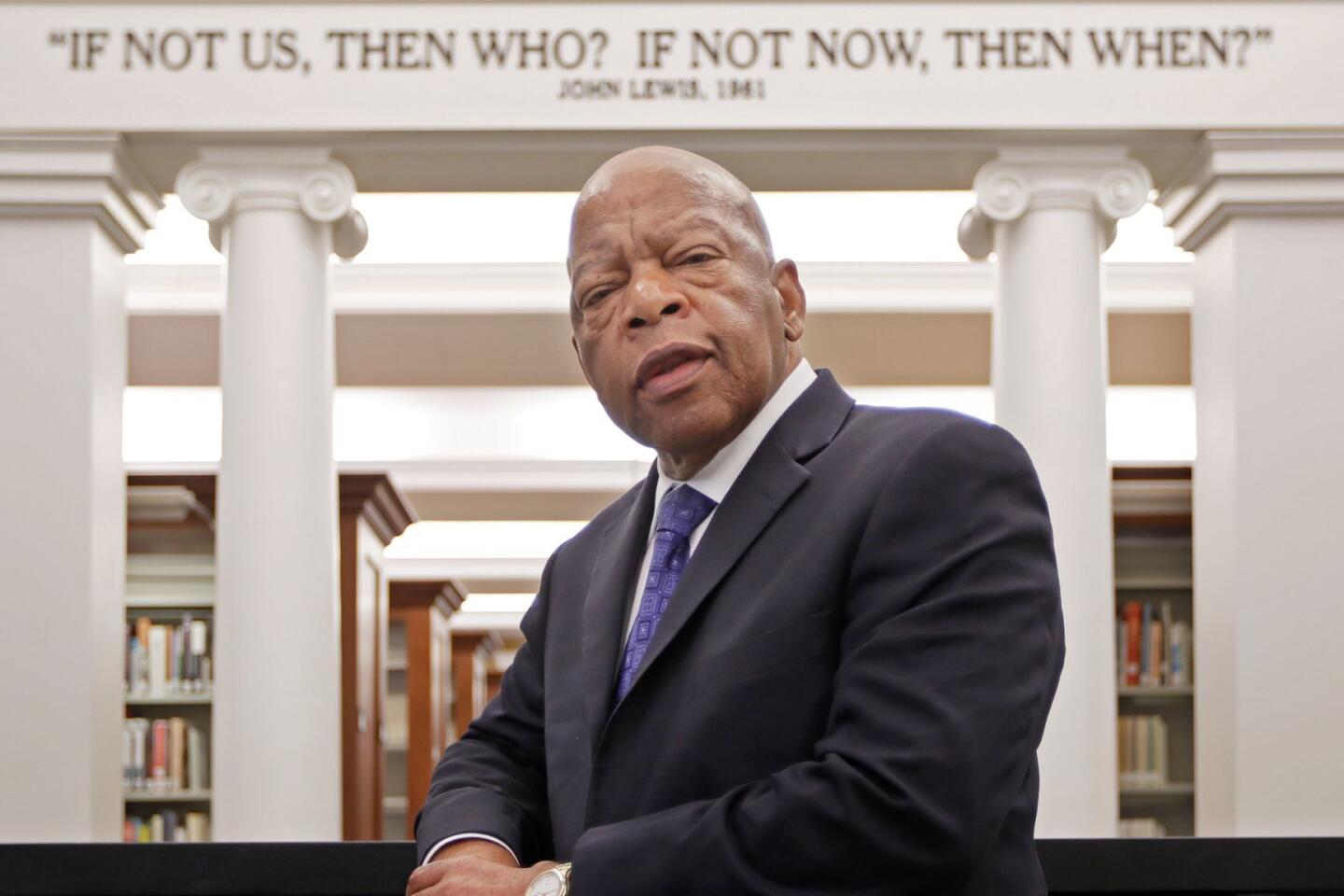

Rep. John Lewis famously shed his blood at the foot of a Selma, Ala., bridge in a 1965 demonstration for Black voting rights, and went on to become a 17-term Democratic member of Congress. An inspirational figure for decades, Lewis was one of the last survivors among members of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s inner circle. He was 80.

(Mark Humphrey / Associated Press) 10/25

Country music firebrand and fiddler Charlie Daniels started out as a session musician, which included playing on Bob Dylan’s 1969 album “Nashville Skyline,” and beginning in the early 1970s toured endlessly with his own band, sometimes doing 250 shows a year. In 1979, Daniels had a crossover smash with “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” which topped the country chart, hit No. 3 on the pop chart and was voted single of the year by the Country Music Assn. He was 83.

(Rick Diamond / Getty Images for IEBA) 11/25

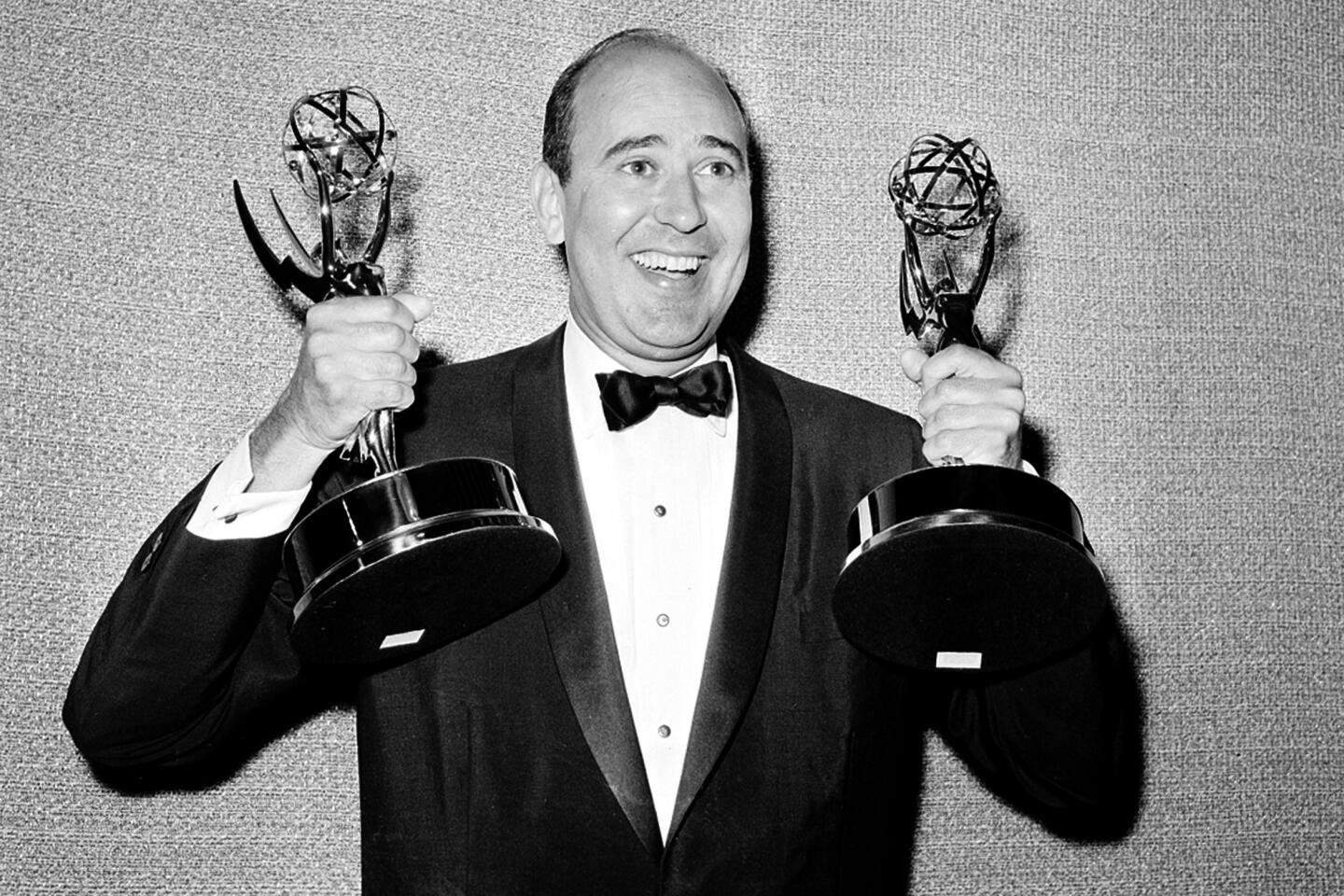

Carl Reiner first came to national attention in the 1950s on Sid Caesar’s “Your Show of Shows,” where he wrote alongside Mel Brooks, Neil Simon and other comedy legends. He later created “The Dick Van Dyke Show,” one of TV’s most fondly remembered sitcoms, and directed hit films including “The Comic” (1969), starring Van Dyke; “Where’s Poppa?” (1970), starring George Segal and Ruth Gordon; “Oh, God!” starring George Burns and John Denver; and four films starring Steve Martin. He was 98.

(Associated Press ) 12/25

The flamboyant, piano-pounding Little Richard roared into the rock ‘n’ roll spotlight in the 1950s with hits such as “Tutti-Frutti,” “Long Tall Sally” and “Good Golly, Miss Molly.” The Georgia native’s raucous sound fused gospel

fervor and R&B sexuality, profoundly influencing the Beatles, James Brown (who succeeded him in one of his early bands), Jimi Hendrix (one of his backup musicians in the mid-’60s) and Bruce Springsteen. He was 87.

(Boris Yaro / Los Angeles Times) 13/25

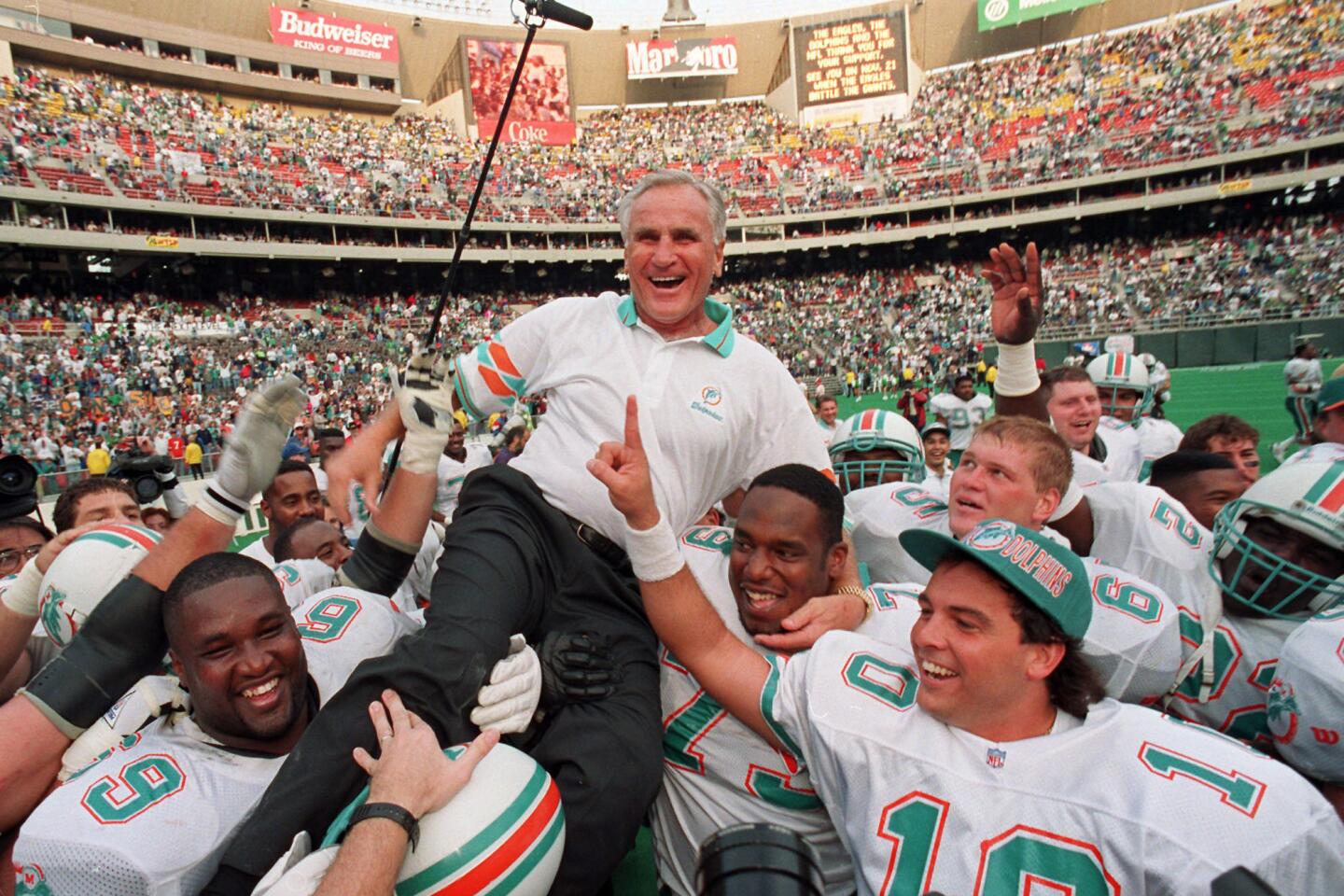

Don Shula was the NFL’s winningest coach, leading the 1972 Miami Dolphins to the league’s only undefeated season. He coached the Baltimore Colts to one Super Bowl and the Dolphins to five, winning Lombardi Trophies after the 1972 and ’73 seasons. He was 90.

(ASSOCIATED PRESS) 14/25

Former Egyptian

President Hosni Mubarak crushed dissent for decades until the 2011 Arab Spring movement drove him from power. During his presidency, which spanned nearly 30 years, he protected Egypt’s stability as intifadas roiled Israel and the Palestinian territories, the U.S. led two wars against Iraq, Iran fomented militant Shiite Islam across the region and global terrorism complicated the divide between East and West. He was 91.

(Sameh Sherif / AFP/Getty Images) 15/25

Among his 40-odd films,

burly Brian Dennehy played a sheriff who jailed Rambo in “First Blood,” a serial killer in “To Catch a Killer” and a corrupt sheriff in “Silverado.” On Broadway, he was awarded Tonys for his roles in “Death of a Salesman” (1999) and “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” (2003). He was 81.

(Dia Dipasupil) 16/25

Singer-songwriter John Prine broke onto the folk scene in 1971 with a self-titled album that included two songs brought to broader audiences by Bette Midler and Bonnie Raitt: “Hello in There” and “Angel From Montgomery,” respectively. In 2019, he was elected to the Songwriters Hall of Fame. He was 73.

(Frazer Harrison / Getty Images for Stagecoach) 17/25

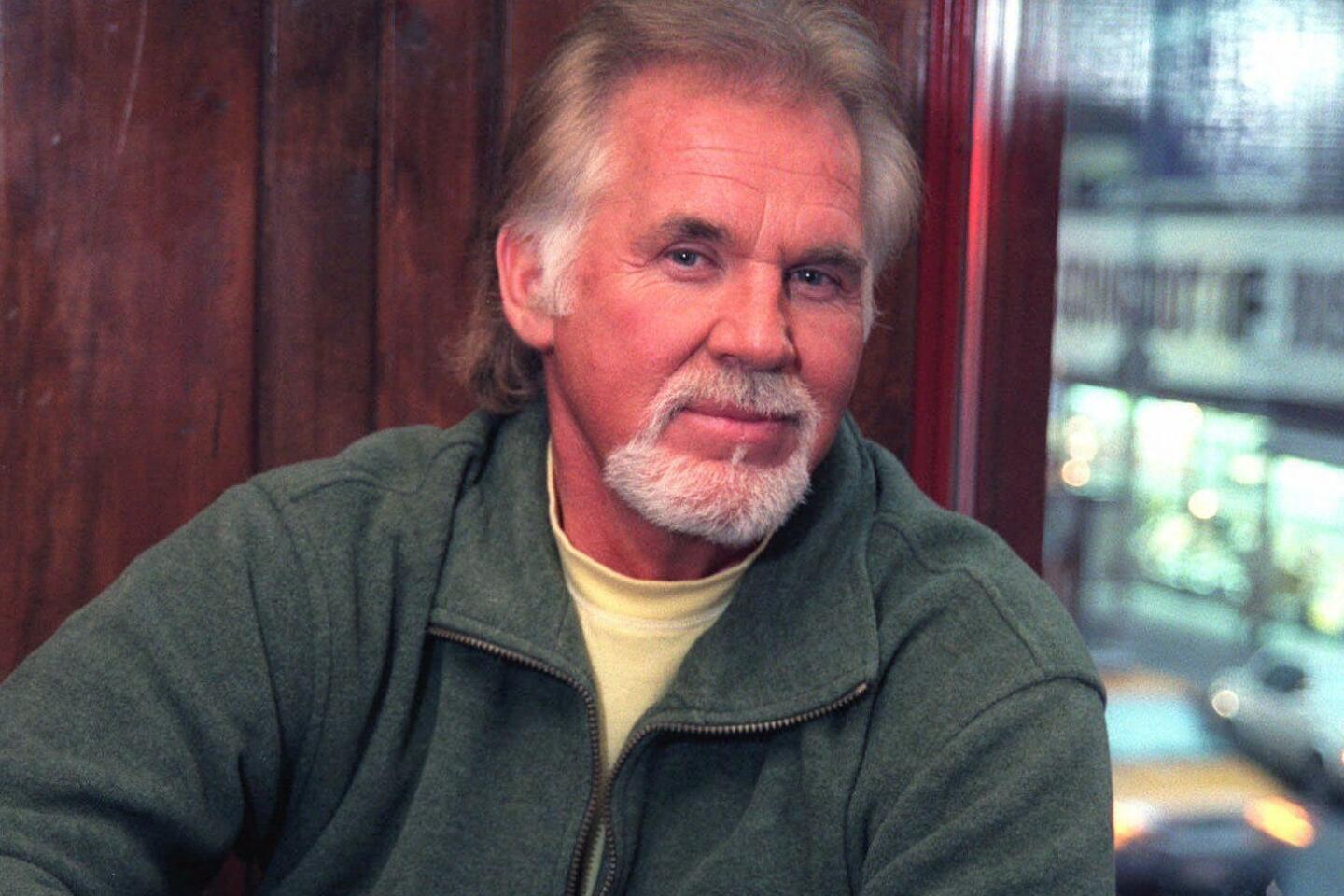

Country singer Kenny Rogers racked up an impressive string of hits — initially as a member of The First Edition starting in the late 1960s and later as a solo artist and duet partner with Dolly Parton — and earned three Grammy Awards, 19 nominations and a slew of accolades from country-music awards shows. Country purists balked at his syrupy ballads, but his fans packed arenas that only the titans of rock could fill. He was 81.

(Suzanne Mapes / Associated Press) 18/25

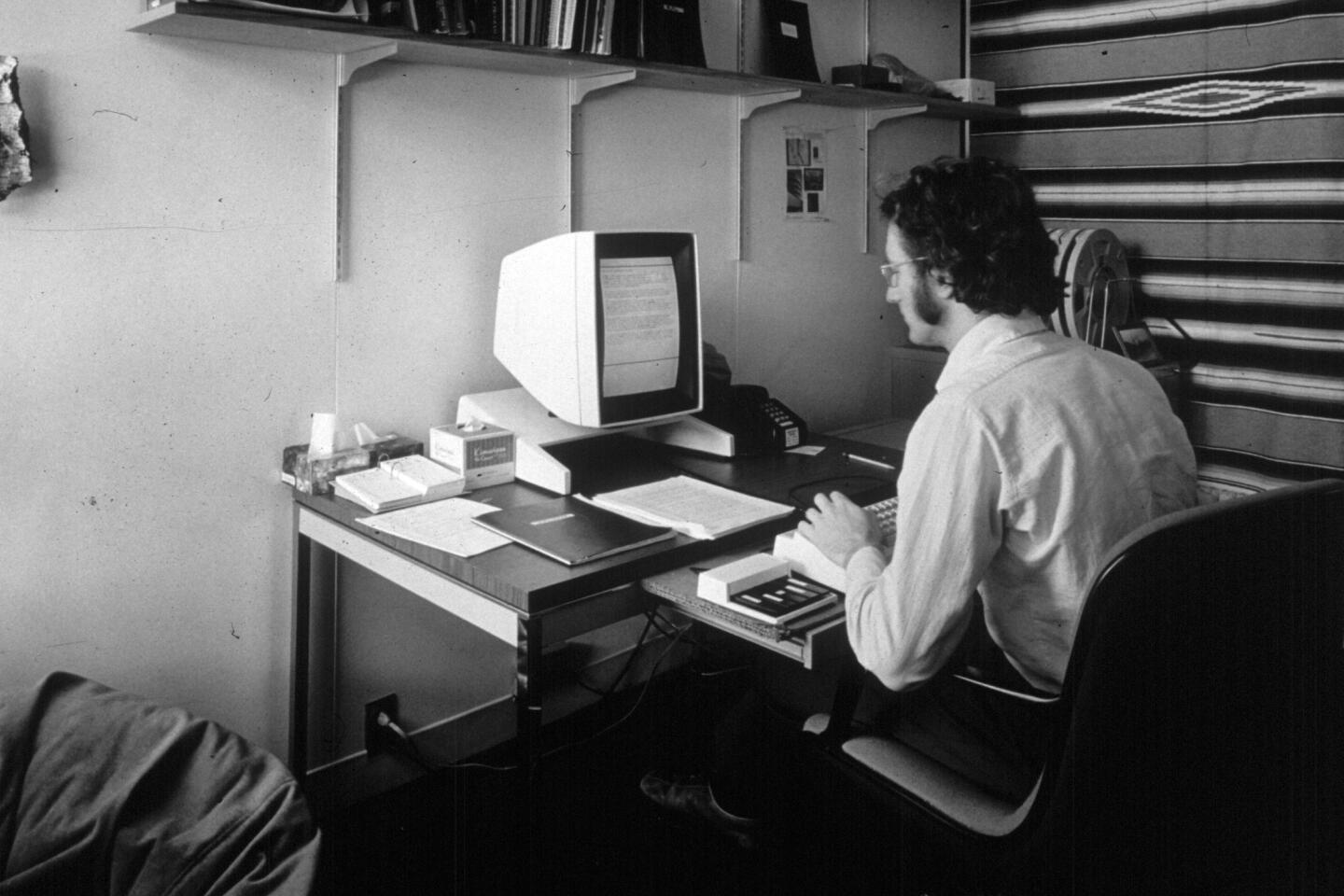

Xerox researcher Larry Tesler pioneered concepts that made computers more user-friendly, including moving text through cut, copy and paste. In 1980, he joined Apple, where he worked on the Lisa computer, the Newton personal digital assistant and the Macintosh. He was 74.

(AP) 19/25

Ski industry pioneer Dave McCoy transformed a remote Sierra peak into the storied Mammoth Mountain Ski Area. Over six decades, it grew from a downhill depot for friends to a profitable operation of 3,000 workers and 4,000 acres of ski trails and lifts, a mecca for generations of skiers and boarders. He was 104. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

20/25

Screen icon

Kirk Douglas brought a clenched-jawed intensity to an array of heroes and heels, receiving Oscar nominations for his performances as an opportunistic movie mogul in the 1952 drama “The Bad and the Beautiful” and as Vincent van Gogh in the 1956 drama “Lust for Life.” As executive producer of “Spartacus,” Douglas helped end the Hollywood blacklist by giving writer Dalton Trumbo screen credit under his own name. He was 103.

(Annie Wells / Los Angeles Times) 21/25

“Queen of Suspense”

Mary Higgins Clark became a perennial best-seller, writing or co-writing “A Stranger Is Watching,” “Daddy’s Little Girl” and more than 50 other favorites. Her sales topped 100 million copies, and many of her books, including “A Stranger is Watching” and “Lucky Day,” were adapted for movies and television. She was 92.

(Associated Press) 22/25

Fred Silverman was the head of programming at CBS, where he championed a string of hits including “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” “All in the Family,” “MASH” and “The Jeffersons.” Later at ABC, he programmed “Laverne & Shirley,” “The Love Boat,” “Happy Days” and the 12-hour epic saga “Roots.” He was 82.

(Associated Press) 23/25

Former California

Rep. Fortney “Pete” Stark Jr. represented the East Bay in Congress for 40 years. The influential Democrat helped craft the Affordable Care Act, the signature healthcare achievement of the Obama administration, and also created the 1986 law best known as COBRA, which allows workers to stay on their employer’s health insurance plan after they leave a job. He was 88.

(Associated Press) 24/25

News anchor

Jim Lehrer appeared 12 times as a presidential debate moderator and helped build “PBS NewsHour” into an authoritative voice of public broadcasting. The program, first called “The Robert MacNeil Report” and then “The MacNeil-Lehrer Report,” became the nation’s first one-hour TV news broadcast in 1983. Lehrer was 85.

(David McNew / Getty Images) 25/25

Terry Jones was a founding member of the Monty Python troupe who wrote and performed for their early ’70s TV series and films including “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” in 1975 and “Monty Python’s Life of Brian” in 1979. After the Pythons largely disbanded in the 1980s, Jones wrote books on medieval and ancient history, presented documentaries, wrote poetry and directed films. He was 77.

(Associated Press) Mickey Rooney, her costar of the ‘40s, learned about her death at Downingtown, Pa., where he is appearing in summer stock. Said Rooney:

“She was a great talent and a great human being.

“She was — I’m sure — at peace, and has found that rainbow. At least I hope she has.”

She was married five times.

In 1941 she married composer-conductor David Rose. They were divorced in 1944.

In 1945 she married director Vincente Minnelli. They were divorced in 1951 after the birth of a daughter, Liza, now 23 and herself a singing star.

In 1952 she married former test pilot Sid Luft, eight years her elder, who became her business manager and father of two children, Joseph, now 13, and Lorna, now 16. She and Luft were divorced in 1964. The children are with Luft in Los Angeles.

In 1965 she married actor Mark Herron, 18 years her junior. They were divorced in 1968 after she testified that he had beaten her. “Yes, I hit her,” he said, afterward, “but only in self-defense.”

In 1968, publicist Thomas E. Green, 30, who had announced marriage plans that Miss Garland later denied, was accused by the singer of stealing two rings worth $110,000. She later refused to press charges, and the rings, recovered, were seized in a government tax action.

Earlier this year — in January and again in March, after the validity of the first ceremony was questioned — Miss Garland married Deans, 12 years her junior. She told newsmen:

“Finally, finally, I am loved.”

She had decided to live permanently in England.

A former owner of a discotheque, Deans found Miss Garland dead in their town house in the Belgravia section of London at 11 a.m. Sunday. He called Scotland Yard. Stricken with grief, he was taken away and into seclusion later by friends.

She had been in good spirits the night before, friends said. There was no indication that she was in failing health, they added.

Miss Garland was born Frances Ethel Gumm in Grand Rapids, Minn., on June 10, 1922. She liked to say she was born in a trunk — backstage. Her parents, Frank and Ethel Gumm, were vaudeville players.

At 30 months she went onstage to sing “Jingle Bells” as part of a Christmas program — and, the story goes, had to be forcibly removed by her father after repeating her song seven times.

Her family moved to California, settling in Lancaster. She and her sisters, billed as the singing Gumm Sisters, did shows in Hollywood. A fellow trouper, George Jessel, suggested she change her name — and she became Judy Garland, “The Little Girl with the Big Voice.” Recalls Jessel:

“She was only 11—but sang like a woman three times her age, with a broken heart.”

An MGM scout spotted her, she was signed up, and, in 1935, made her first film, a two-reel short.

She was on her way to a Hollywood career — and to a unique life style. She became one of the juvenile players at MGM who studied lessons from a tutor, along with lines for her current role, in a dressing room. For Frances Ethel Gumm, stardom was near. And her childhood was suddenly over.

“She never had a chance to become a normal child — or a normal adult,” dancer Bolger, 65, recalled in New York Sunday. “She always had someone hovering over her.

“There should be a time in your life when you can go home at night and forget about show business, but Judy Garland never got to that point.”

[email protected]

MORE ARCHIVAL OBITUARIES

Former San Francisco Mayor Joseph Alioto Dies

John Wayne Dies at 72 of Cancer

Playwright August Wilson Distilled Black America

Ex-Chief Justice Rose Bird Dies of Cancer at 63

Jazz Great Duke Ellington Dies in New York Hospital at 75