John Lewis, civil rights icon and longtime congressman, dies

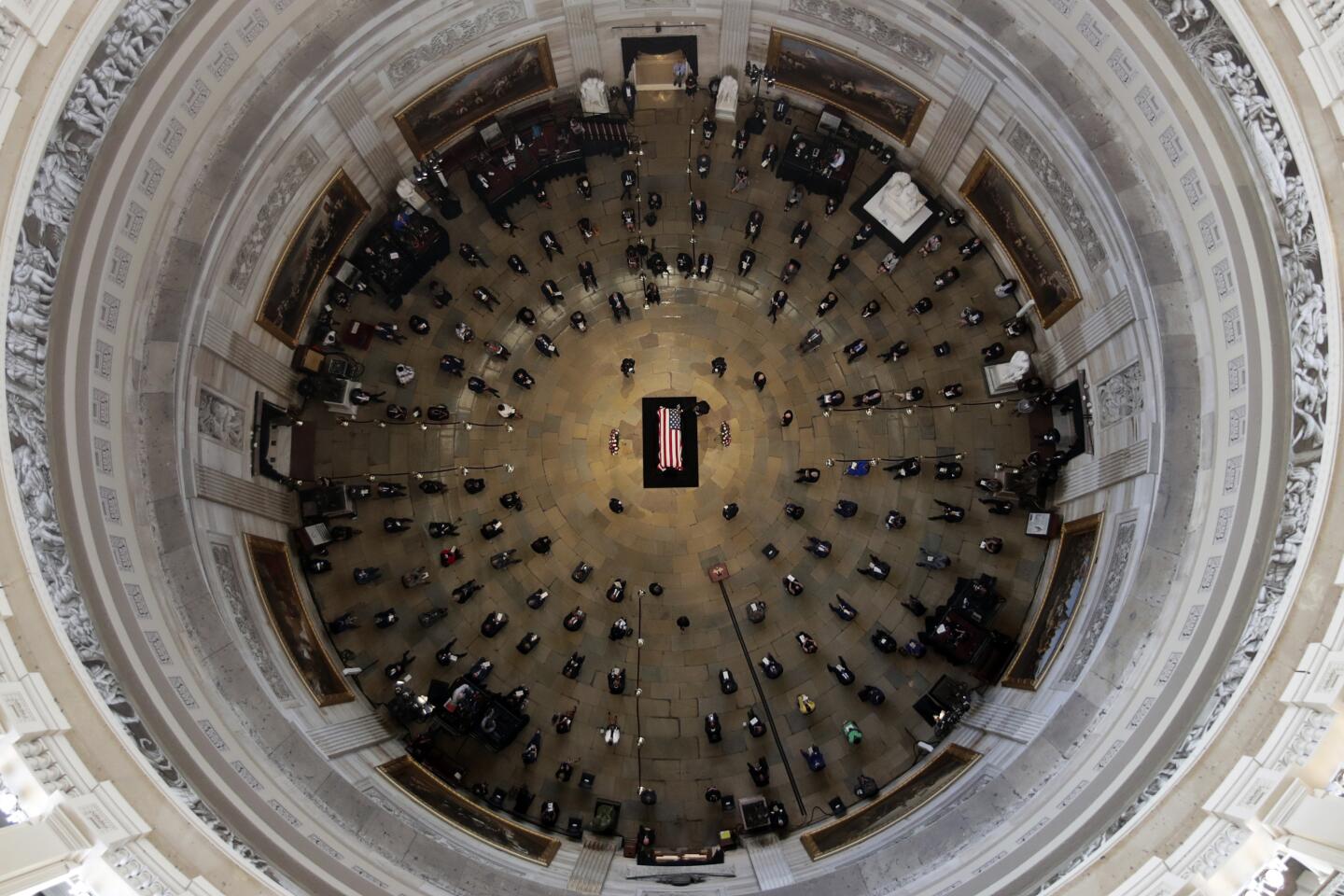

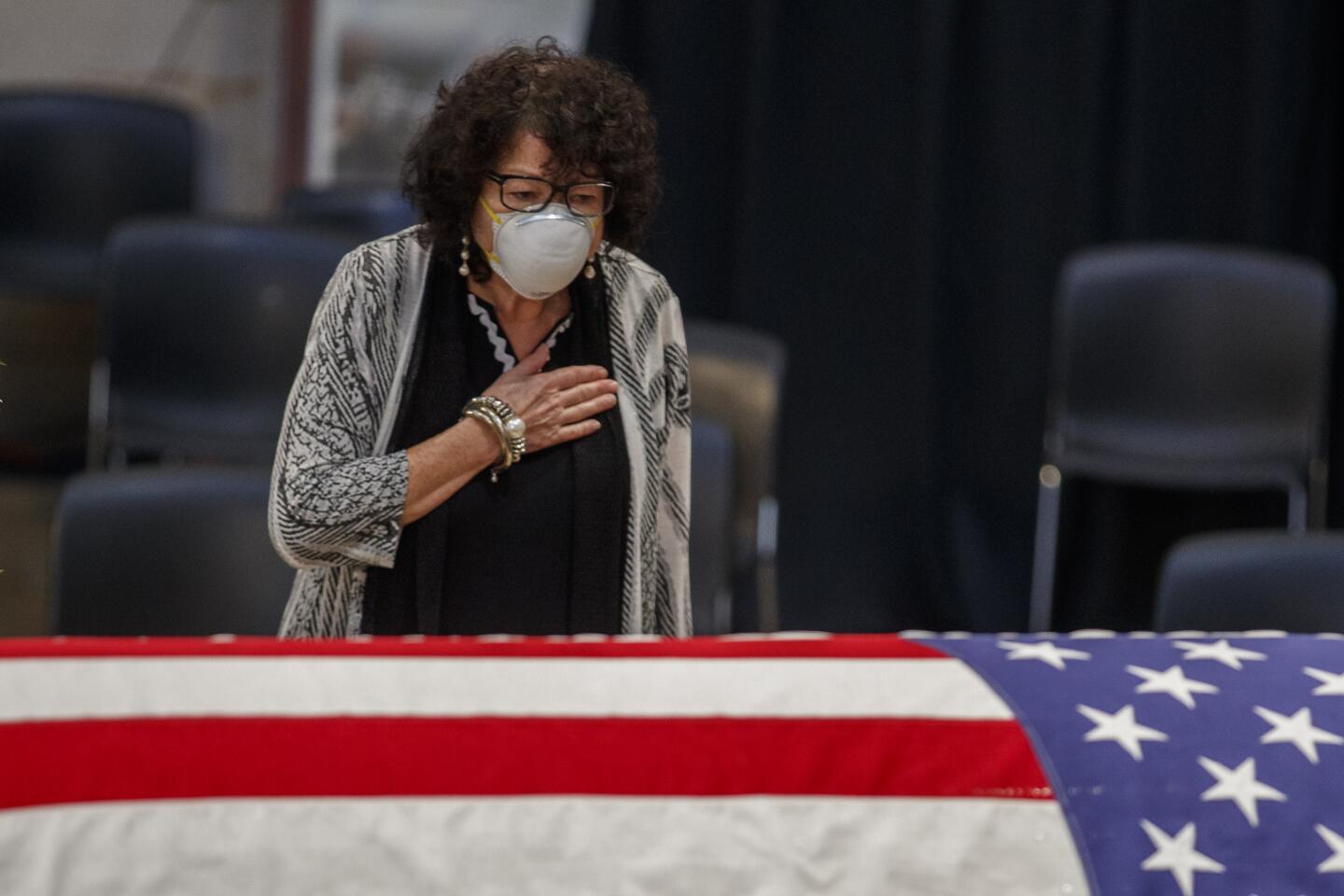

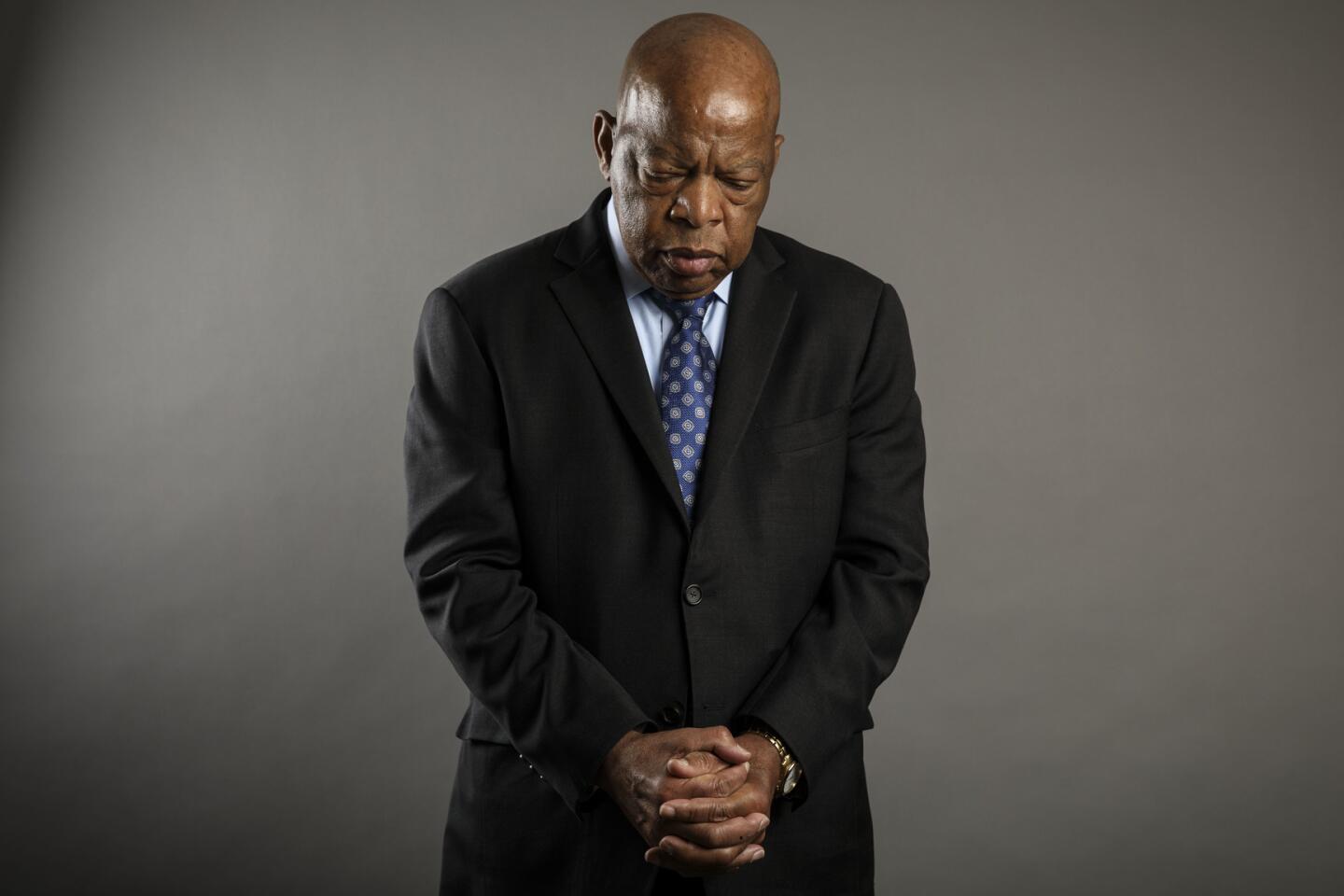

WASHINGTON — Rep. John Lewis, an iconic pioneer of the civil rights movement who famously shed his blood at the foot of a Selma, Ala., bridge in the fight for Black voting rights and went on to become a 17-term Democratic member of Congress, died Friday. He was 80.

One of the last survivors among leaders of the 1960s civil rights era and members of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s inner circle, Lewis was diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer in December. Ever the activist, he nonetheless took to the streets again in early June, to join protests near the White House for racial justice that were sparked by police killings of Black people.

Lewis spent much of his life trying to advance civil rights through nonviolent means, beginning with the mobilization for Black voting rights when he was a college student and continuing through the gay rights movement as a senior member of Congress representing Atlanta.

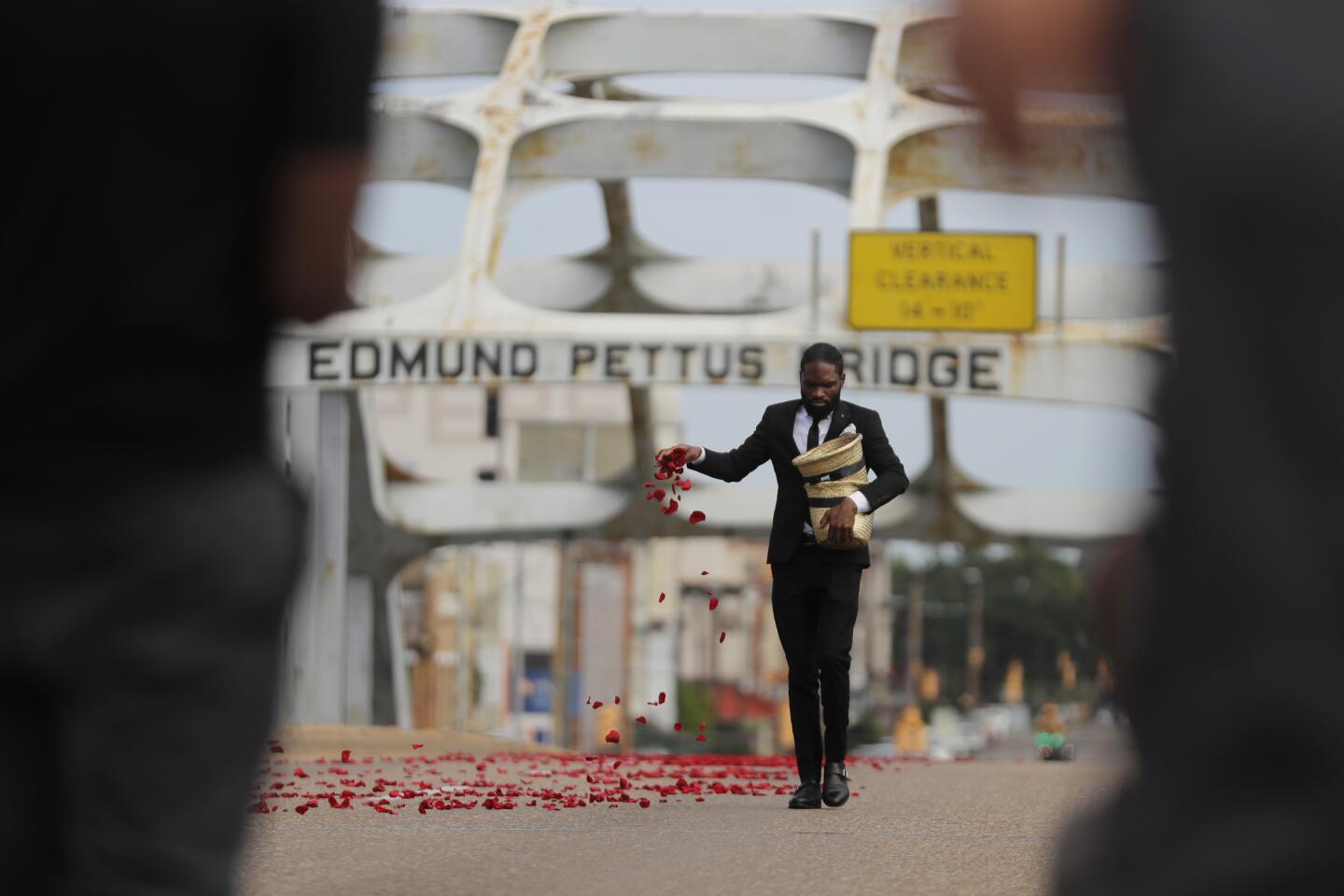

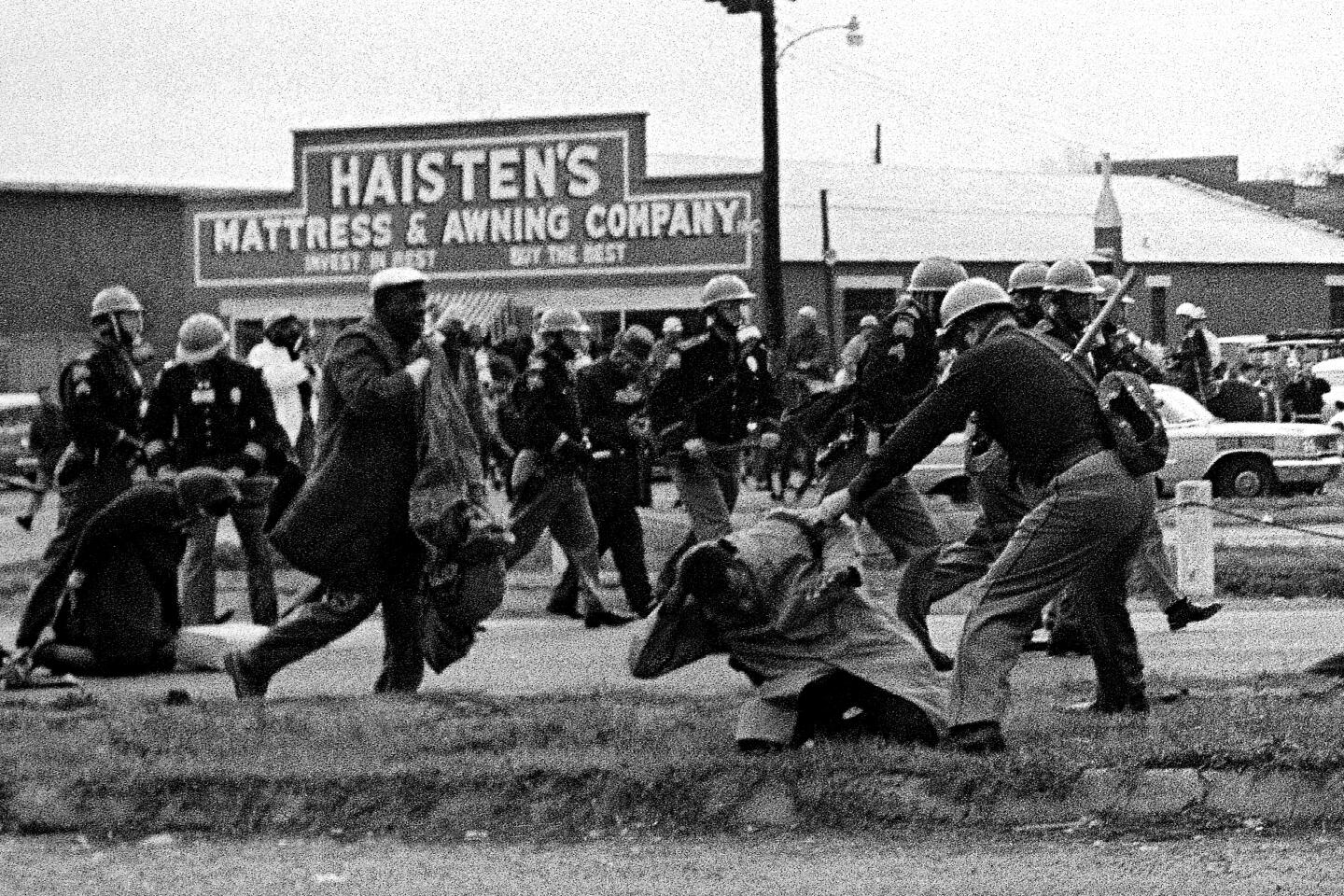

As a 25-year-old man, Lewis helped to plan the peaceful 1965 protest march from Selma to Montgomery that was one of the seminal moments of the civil rights movement. The clash between protesters and the Alabama state troopers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, called “Bloody Sunday,” spurred protests in 80 American cities and Congress’ passage of the Voting Rights Act, which President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law five months later.

The protesters “literally, in my estimation, wrote the Voting Rights Act with our blood and with our feet on the streets of Selma, Alabama,” Lewis said in a 1985 interview for the documentary “Eyes on the Prize.”

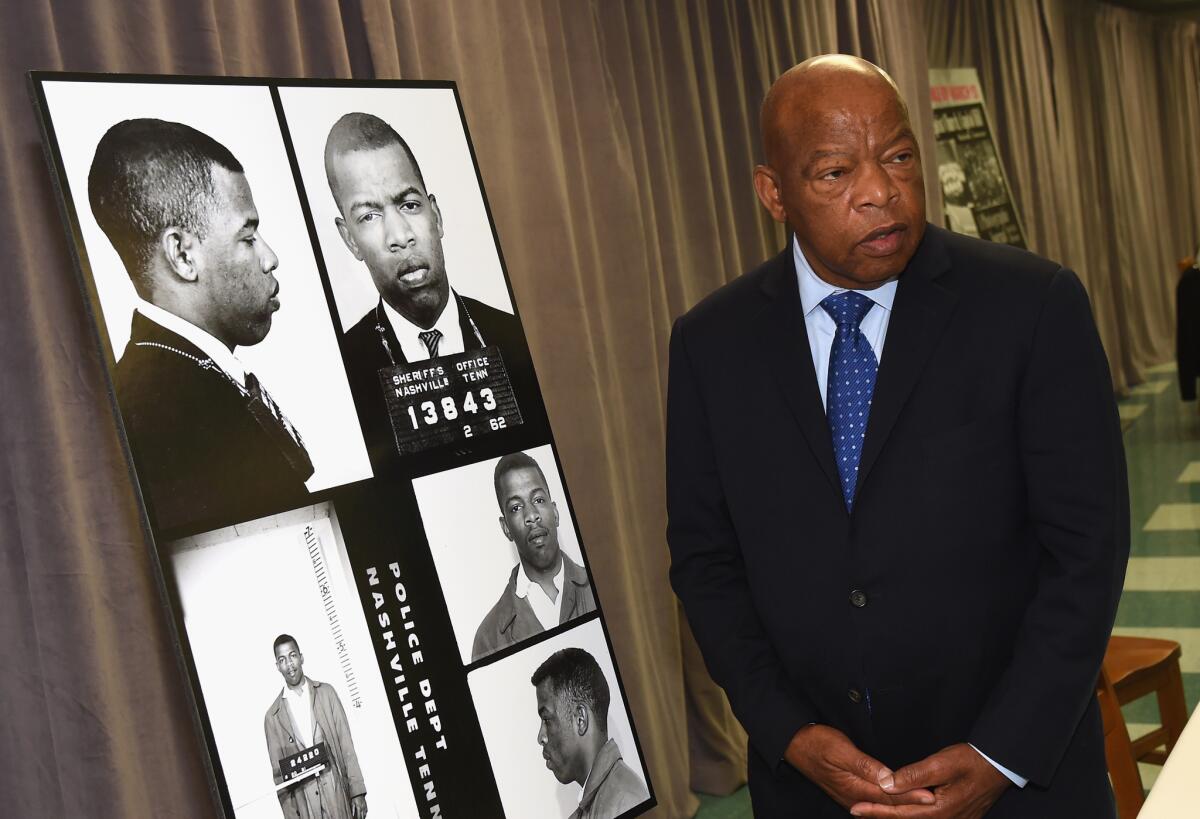

It wasn’t the first nor the last time Lewis would be beaten. He often said he was arrested or jailed 40 times throughout the 1960s.

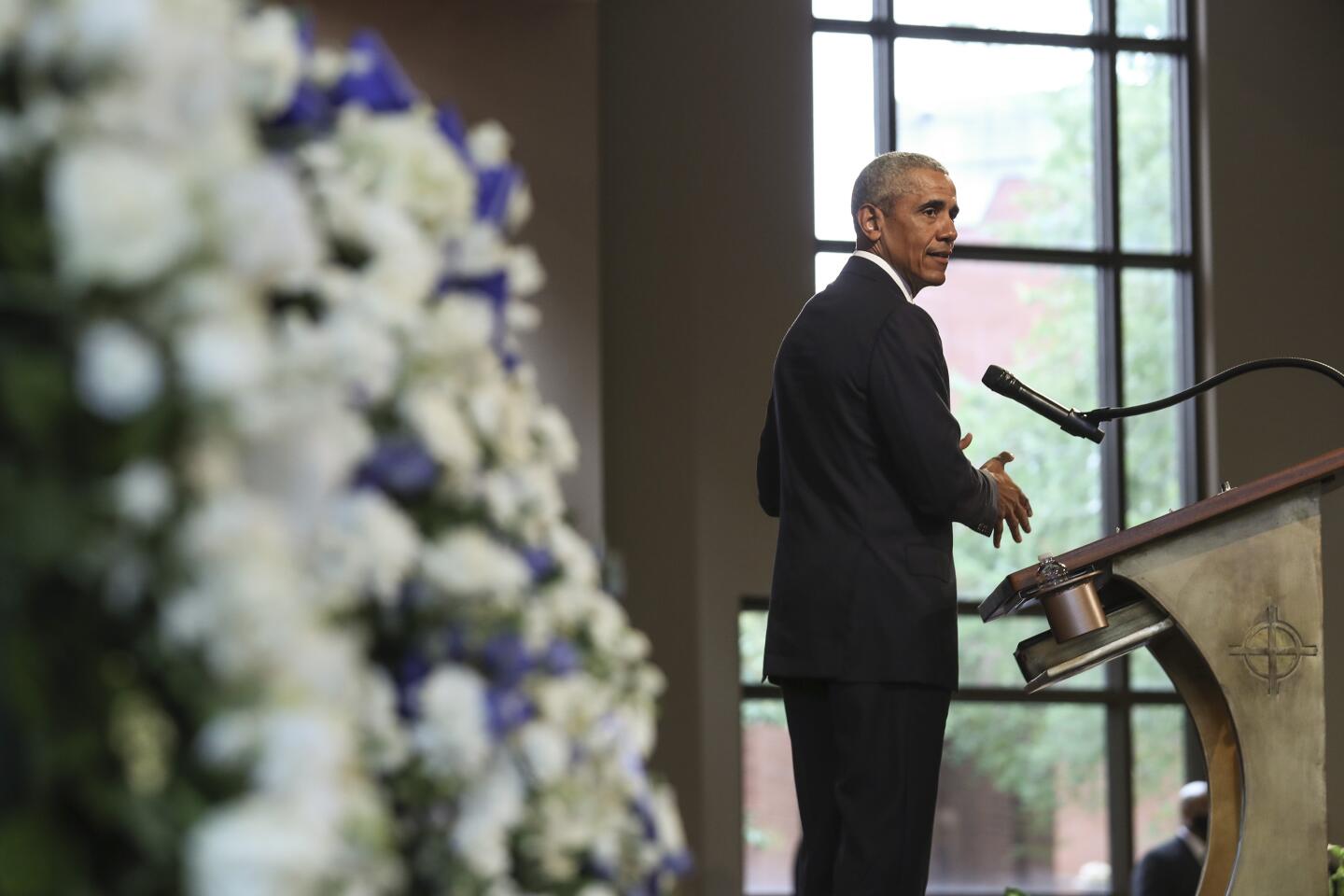

Fifty years after Bloody Sunday, Lewis marched across the same bridge with the first Black U.S. president, Barack Obama. Earlier this year, Lewis attended the 55th anniversary march — a surprise appearance given his illness.

“I had to be here, as long as I’m breathing,” Lewis said, according to the Rev. Al Sharpton. “Even when I’m not, be sure to keep marching to protect our voting rights.”

Lewis for decades was an inspirational figure for generations of Black political leaders, a living link to the historic struggle for fundamental rights and equality.

“John Lewis was probably the embodiment of the civil rights movement and of the empowerment movement in terms of Blacks running for office, and keeping alive the nonviolent tradition of protest,” Sharpton said.

The role of art in our society is not to reenact history but to offer an interpretation of human experience as seen through the eyes of the artist.

Sharpton, 15 years younger than Lewis, praised the Georgia Democrat for passing down King’s tradition of peaceful protest. Lewis continued to preach that gospel even as many activists turned to the more militant approach of the Black Power movement.

“It took great courage,” Sharpton said. “We saw him not only fighting white racism but standing up to Black rejection of his philosophy.”

In 1977, the new president and fellow Georgian Jimmy Carter named Lewis to be director of ACTION, a federal agency for volunteerism. Four years later Lewis was elected to the Atlanta City Council and, in 1986, to the U.S. House of Representatives. There he became known among Democrats as the “conscience of the Congress.”

As the civil rights movement expanded to other minority groups, Lewis early on joined the battle to extend the Civil Rights Act to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. Legislation called the Equality Act faced skepticism from some civil rights groups concerned about the unintended consequences of reopening the 1965 landmark law, fearful that they could lose some of its federal protections in the process.

Chad Griffin, former president of the Human Rights Campaign, credits Lewis with helping to build support for the legislation. “We have so far to go, but we owe so much of the progress that we have made to John Lewis,” Griffin said.

“Sometimes people ask me, ‘Why do you take such a strong stand for gay rights, for marriage equality?’” Lewis said at a 2014 Human Rights Campaign event. “My simple answer is I fought too hard and too long against discrimination based on race and color not to stand up for discrimination today based on sexual orientation.”

Lewis’ politics had grown more partisan in the last decade, said David Garrow, a civil rights historian and King biographer. He was frequently counted as among the most progressive Democrats in the House, a reflection of his very Democratic district. He boycotted the 2001 inauguration of President George W. Bush, arguing that Bush was not legitimately elected. He did the same in 2017 when President Trump was sworn in.

“The John Lewis I saw in Congress is this really angry, uber partisan. I have trouble connecting that John Lewis to the John Lewis of the 1960s,” Garrow said.

The phone call that changed Police Chief Kevin Murphy’s life came late on a Friday afternoon last year: The mayor of this cordial Southern capital asked him to greet a delegation arriving the next morning from Washington.

John Robert Lewis was born Feb. 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Ala., to sharecroppers. When Lewis was 4 years old, his father bought a farm, where his son’s duty was to care for the chickens. Lewis joked in a 2013 C-SPAN interview that he engaged in his first nonviolent protest when his parents tried to prepare one of his flock for Sunday dinner.

Lewis attended segregated public schools in rural Pike County. As a teenager, he listened to radio broadcasts by King and news of the Montgomery bus boycott. While his parents and grandparents urged him to come to terms with Jim Crow laws and segregation, the burgeoning civil rights movement inspired Lewis to do the opposite.

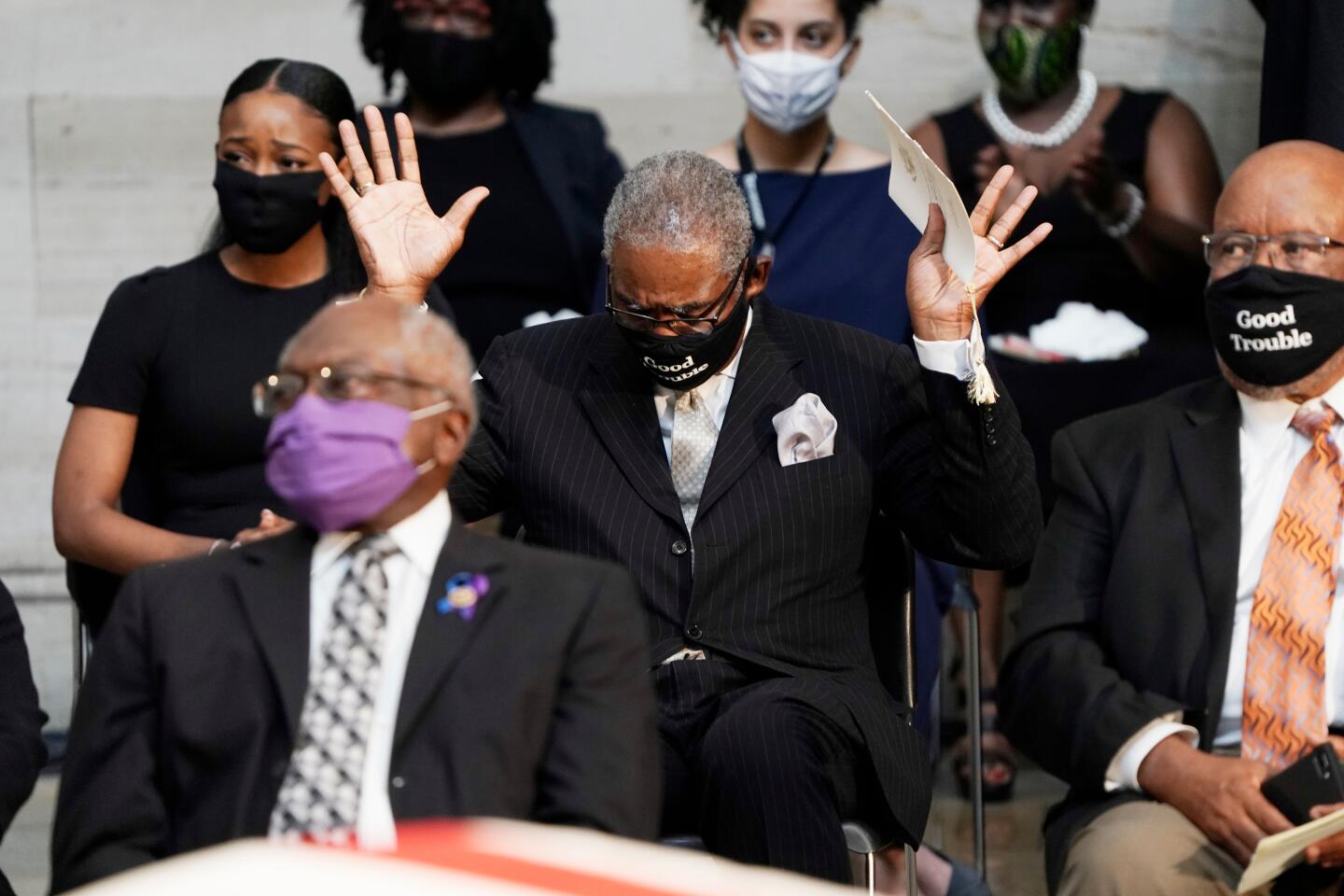

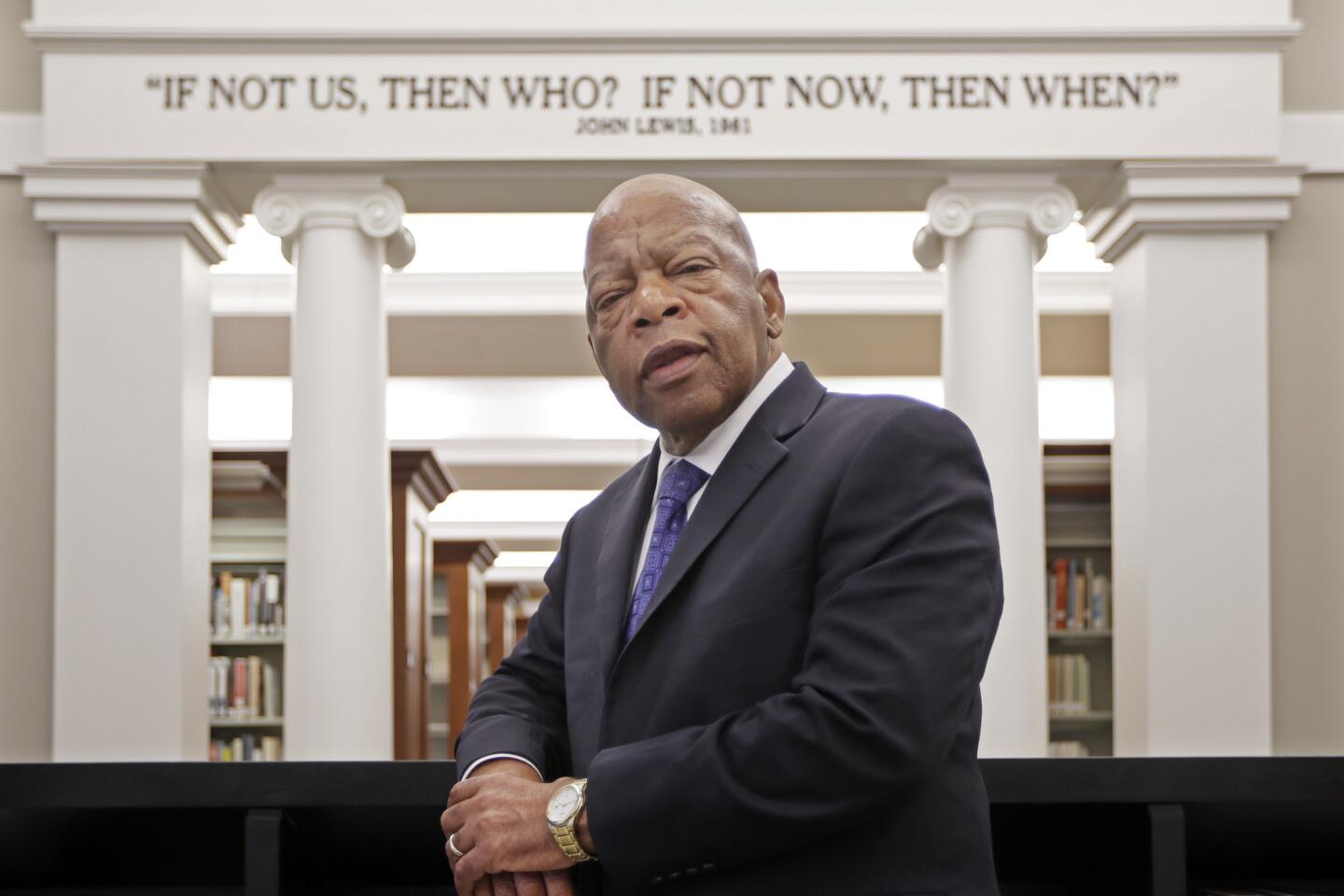

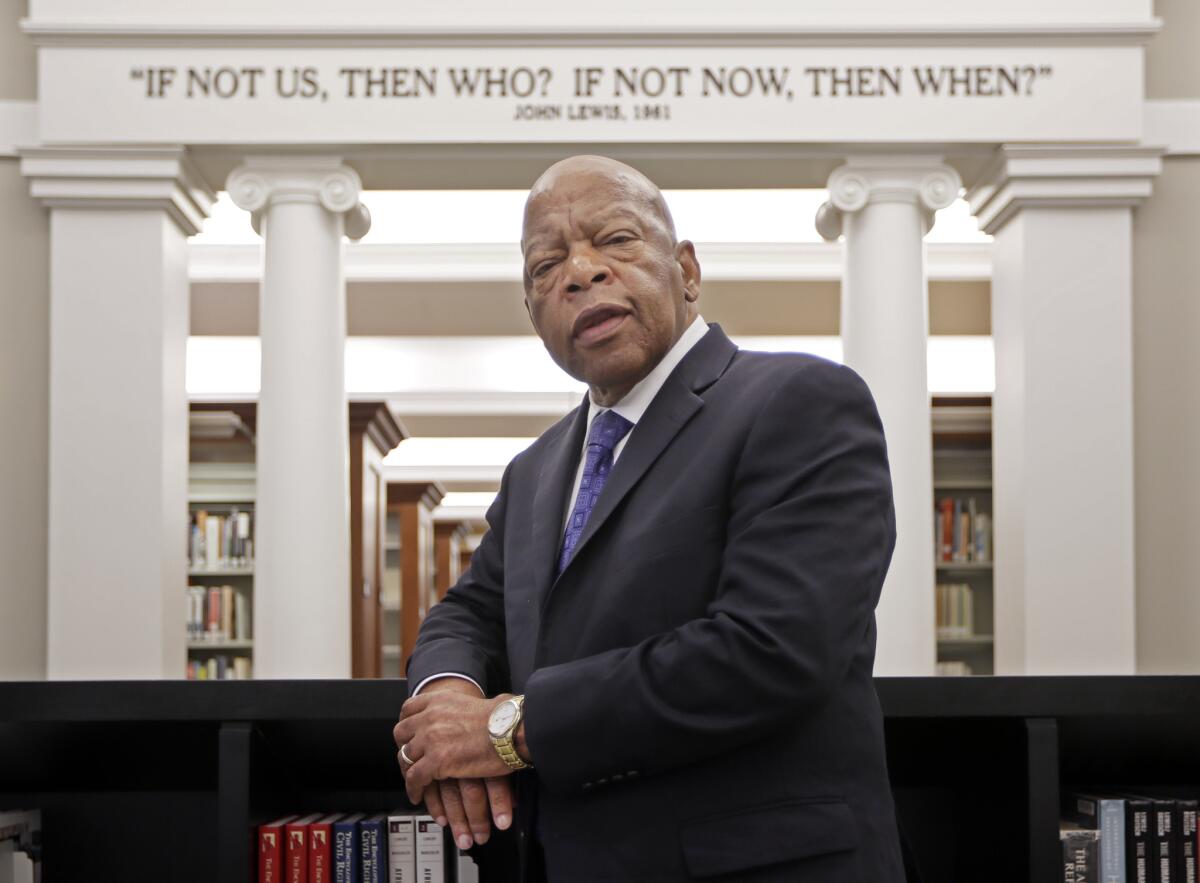

As a student at Fisk University in Nashville, he began organizing sit-in demonstrations at segregated lunch counters. In February 1960, he was one of 89 students arrested at a sit-in. It was the first time he engaged in “good trouble, necessary trouble” — a phrase that he would repeat for decades.

“That was my first arrest. That was my introduction to Southern jails,” Lewis said in the C-SPAN interview. “I grew up sitting down on those lunch counter stools and going to jail in places like Nashville, Birmingham, Jackson, Miss., and Atlanta, Ga., and a few other places across the South.”

By 1961, he was volunteering for the Freedom Rides, challenging segregation by sitting among white people on buses in Southern cities, not in the rear sections designated for “colored” people.

Sometimes he was beaten and arrested. On May 9, 1961, as his bus stopped at a Greyhound station in Rock Hill, S.C., he and his companions were beaten by Elwin Wilson, a white man Lewis didn’t officially meet until nearly 50 years later. Wilson visited Lewis’ congressional office in 2009 to formally apologize.

“It demonstrated the power of nonviolence, the power of love, the power of the way of peace, to be reconciled,” Lewis said.

By the time he was just 23, Lewis was known as one of the “Big Six” national student leaders in the civil rights movement. He was chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which organized student activism including sit-ins, voter registration drives and the Mississippi Freedom Summer, a 1964 project to register Black voters in the state. The role at SNCC brought him to Atlanta, a city that he would call home for the rest of his life.

Lewis helped organize the 1963 March on Washington. Two years later, he planned the Selma-to-Montgomery march for which he’d be best remembered, but which might have ended his life.

“I was hit in the head by a state trooper with a nightstick and had a concussion at the bridge. I remember my legs going out from under me and falling to the ground. I thought it was the last protest. I thought I was going to die and I kept thinking about what was happening to the other people,” Lewis said in 2013. “I don’t recall 48 years later how I made it across that bridge, back through the streets of Selma.”

Since 2015, activists have pushed to rename the Pettus bridge, which was named for a man who was a Confederate general, U.S. senator and head of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan. A proposed alternative: the John Lewis Bridge.

A turning point in the Southern civil rights movement and Lewis’ role in it came in 1966, when Lewis lost the chairmanship of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to Stokely Carmichael. The group adopted “black power” as its organizing principle — a shift that Lewis believed limited the organization’s effectiveness.

“The John Lewis of 1960-66 is, to my mind, a remarkably principled, courageous, committed young activist whose grounding in principle is just as fundamental as King’s,” Garrow said.

In 1968, Lewis married Lillian Miles, a Los Angeles native who became Lewis’ closest political advisor. The Rev. Martin Luther King Sr. conducted the ceremony.

Lewis’ political career began in 1981, when he was elected to the Atlanta City Council. Five years later, he was elected to Congress, to a seat he has held since then.

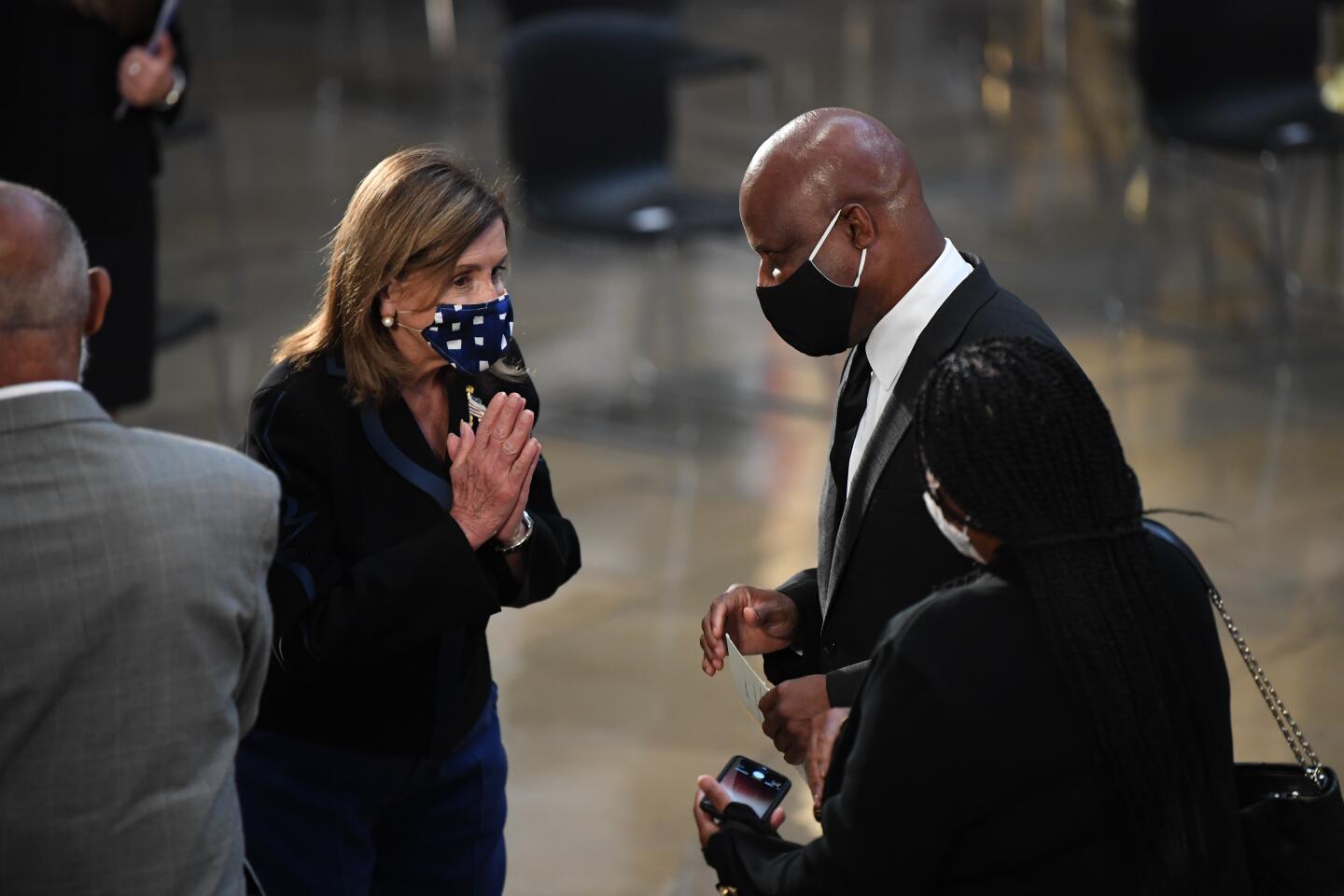

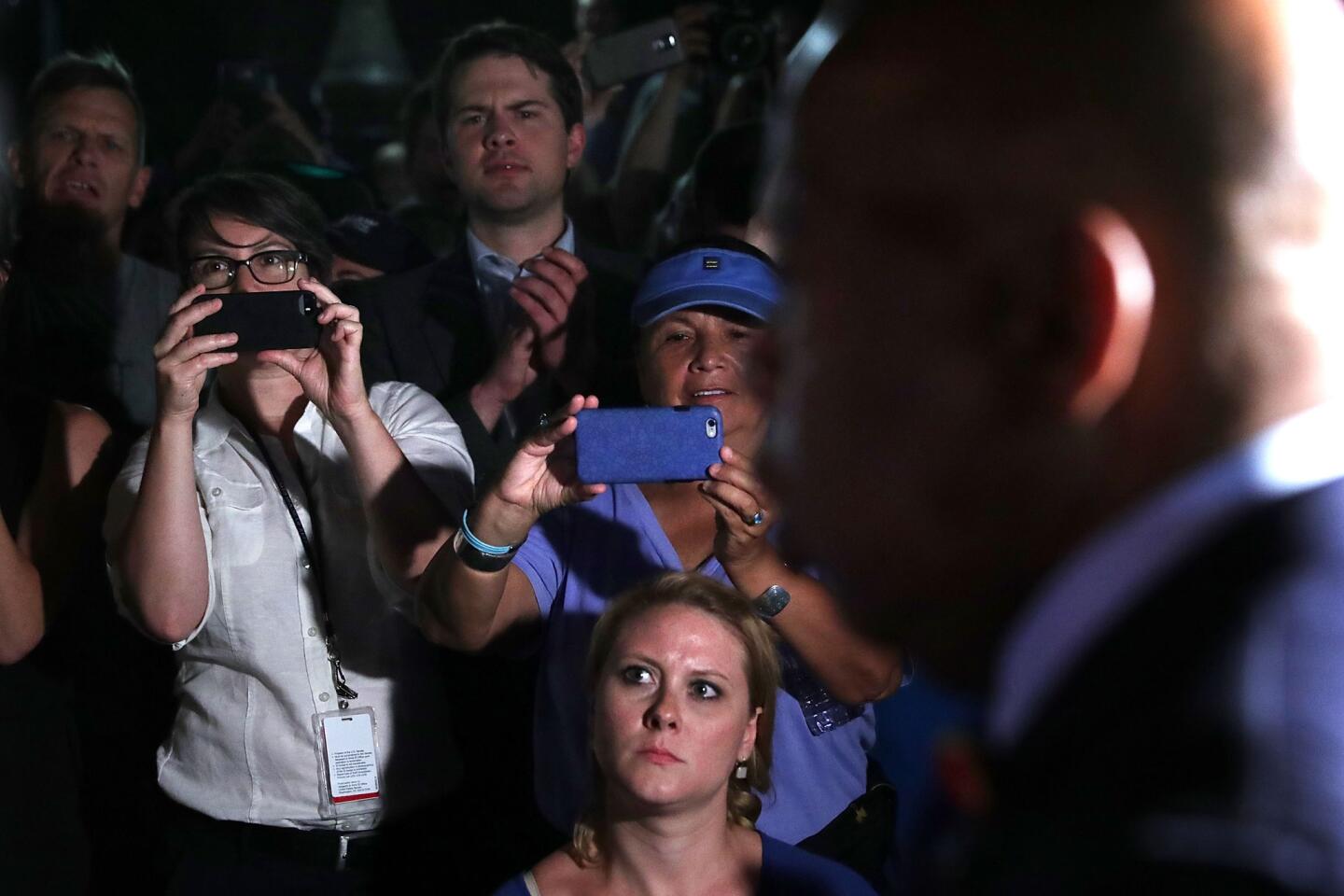

While serving in the House of Representatives, Lewis became a leader and inspirational figure among his fellow Democrats. On major legislation, he often gave a closing speech that roused his party faithful. In the wake of the shooting massacre at the gay nightclub the Pulse, in Orlando, Fla., in 2016, he led a “sit in” on the House floor to protest Republicans’ refusal to act on gun-safety legislation.

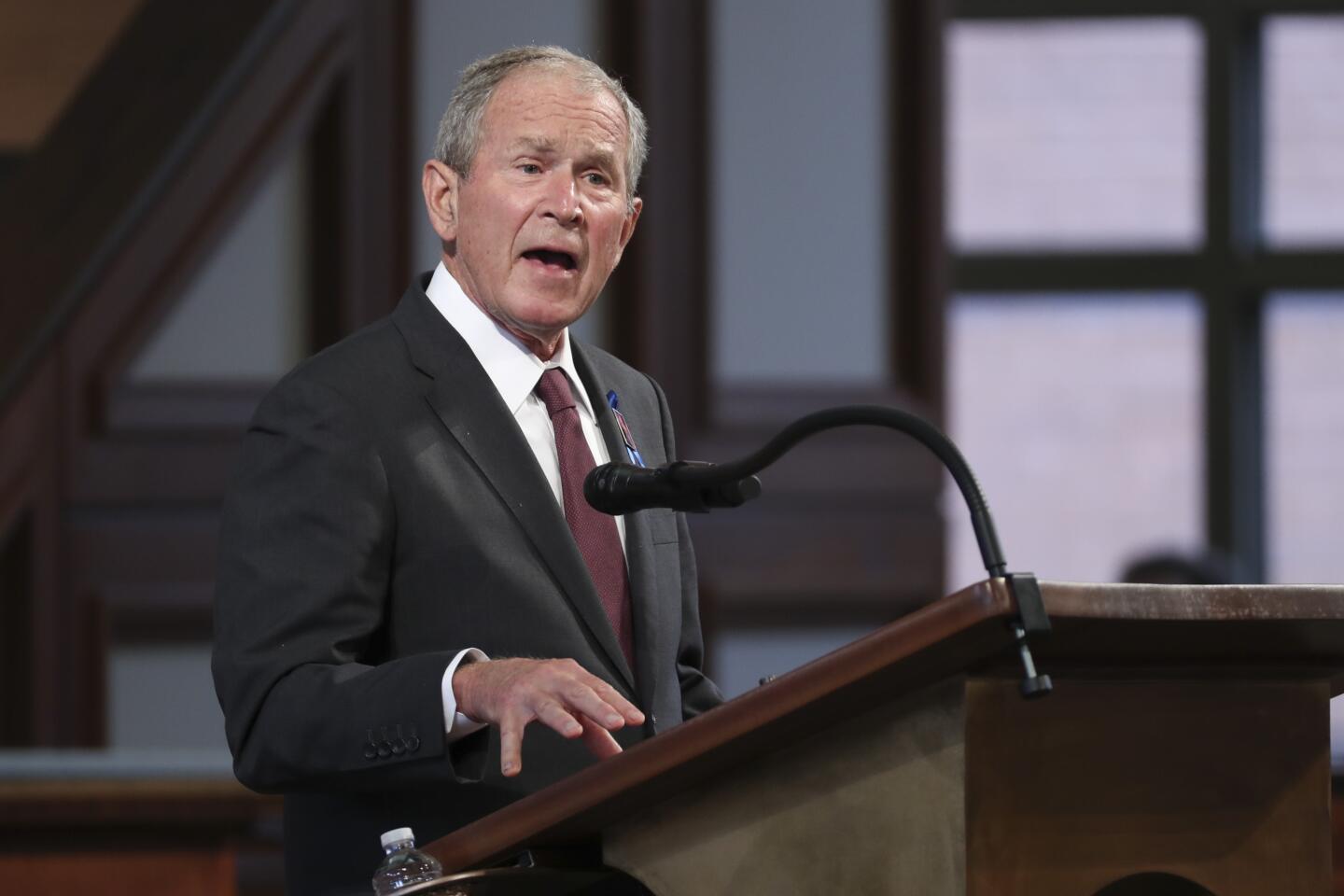

For the first 15 years of his congressional career, Lewis repeatedly introduced a bill to create a national African American history museum, legislation that was repeatedly blocked by Sen. Jesse Helms, a Republican and onetime segregationist from North Carolina. Helms retired in 2003 and that year Lewis was able to pass his bill and President George W. Bush signed it into law. The museum opened on the National Mall in 2016.

In 2011, President Obama awarded Lewis the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

“Generations from now, when parents teach their children what is meant by courage, the story of John Lewis will come to mind,” Obama said at the ceremony. Lewis, he went on, is “an American who knew that change could not wait for some other person or some other time, whose life is a lesson in the fierce urgency of now.”

Times staff writer Janet Hook contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.