Old encyclopedia opens a door to the Internet

If you haven’t heard of Baroness Barbe-Julie von Krudener, you’ve missed a good yarn.

She was a child of wealth and privilege in the 19th century Governorate of Livonia. A life of social climbing, dalliance, literary ambition and finally religious conversion led to a Rasputin-like influence over Alexander I, czar of Russia.

And that was not all.

I discovered the now obscure story of the baroness while paging through the “Jerez-Libe” volume of my 1950 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

My father bought the 24-volume set when I was a child. Growing up in our cracker-box house on Mt. Washington, I understood it to be a proud symbol of our erudition, as well as our emerging middle-class wealth.

When the Britannica became mine nearly two decades ago, its place in my working library was already taken by the more modern and relevant Encyclopedia Americana. The world’s most recognized embodiment of popular knowledge found its new home at the back of a closet.

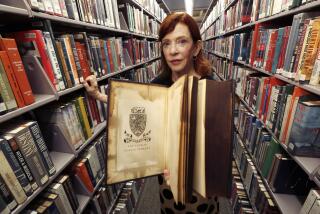

A recent spring cleaning placed it squarely in my line of sight. The realization that its pages had not been touched for at least 20 years — and probably much longer — forced a troubling question: What is a 1950 Encyclopedia Britannica worth?

My first impulse was to go to the Internet. I didn’t find the answers there useful. Estimates ranged from $50 to $750, but none of the respondents seemed to realize that my question was not about money.

Next I took a walk down Spring Street in search of The Last Bookstore, a two-year-old recycler of the printed word. Its website says buyers are always on hand to appraise used books.

The Last Bookstore is tucked away inconspicuously in downtown’s historic core of early 20th century office buildings that were virtually abandoned for decades but are now coming back as urban loft apartments.

I almost walked past it. At the address, I found no sign or showroom window full of bestsellers. A guard standing outside the elegant entrance of the former Crocker Building, now the Spring Arts Tower, pointed to the foyer.

I turned a corner, passed a coffee bar and entered the former bank, now a muted hall two stories high, filled with second-hand books on wooden shelves. A handful of patrons browsed the shelves or lounged with books in hand-me-down chairs.

I didn’t come to ask how much I could get. I already knew the answer from the Last Bookstore’s website under the heading: “What we never take.”

Why, I wanted to know, if they bought classics, philosophy, counterculture, modern literature and children’s books, would they not want encyclopedias.

Manager and head buyer Katie Orphan gave me a straight answer.

“A reference source locked in time is of little purpose,” she said.

Orphan said she could take my treasure on a “donation” basis for 50 cents a book. Eventually she’d find a buyer at $1.

“It’s of decorative value to a set designer, or it might have some kitsch value,” she said.

As for the information, it’s all readily available now on the Internet.

Not surprised, but nonetheless displeased, I went home and randomly dived into the “R” volume in search of something so obscure and so outdated that it would not be in Wikipedia.

Along with the predictable — “Rome,” “Russia,” “rockets” — I found its pages populated by knights and bluebloods whose social milieu had vanished long before publication.

Some of them were worth remembering, like Sir Samuel Romilly, an early 20th century lawyer who dedicated his life — mostly without success — to repealing capricious capital laws.

Others seemed quaint and expendable. I faintly recall my father noting one character flaw in his otherwise beloved Britannica. He thought it was hurriedly updated to catch up with the political, scientific and technological changes wrought by World War II, but its DNA still carried the Victorian sentiments and prose style of the 19th century.

I found evidence to support his view.

A lone paragraph on Erwin Rommel, the most memorable German general of the war, ends with the Nazi’s announcement of his death — failing to mention his forced suicide after the plot on Hitler’s life.

My chief complaint is the tortured composition of biography: John Augustus Roebling is introduced as an American engineer born in Muhlhausen, Prussia. By contrast, Wikipedia’s first paragraph tells us what we want to know: He designed the Brooklyn Bridge.

After 2010, the Britannica ceased publishing its print volumes and cast its fate in a subscription- and advertising-based online edition. Judging by the evolving profile of one Guillaume Thomas Francois Raynal, I’d say it’s caught its stride.

In the 1950 Britannica he’s a French writer born at St. Geniez and educated at the Jesuit school of Pezenas, the author of a series of “popular but superficial works.”

The online Britannica is much more journalistic, better in fact than Wikipedia: “French writer and propagandist who helped set the intellectual climate for the French Revolution.”

But like Guillaume, every entry I could find in the printed Britannica was developed to greater detail, and usually in more vibrant writing, in the free online democratic Wiki. Everything, it seems, is remembered by someone.

In the face of the evidence, I concede my 1950 Britannica is little more than a cumbersome artifact of an institution losing its grip as the arbiter of all that was important to know.

Despite that sad conclusion, my recent encounter with the Baroness von Krudener has provided the answer I was seeking.

What’s the Britannica worth? I would have never stumbled on the baroness on the Internet. I only found her by browsing through random pages of a book.

I would have never known about her self-destructive path from confidant of Czar Alexander to destitute mystic leading crowds of beggars and rapscallions.

Serendipity.

That’s worth a few more decades on my bookshelf.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.