Column: Lillian Michelson and her one-of-a-kind film library get a digital Hollywood ending

A real Hollywood ending doesn’t always come from Hollywood; sometimes it comes from, gasp, the internet.

Or in this case, the Internet Archive, which has stepped in at the 11th hour to save the Michelson Cinema Research Library.

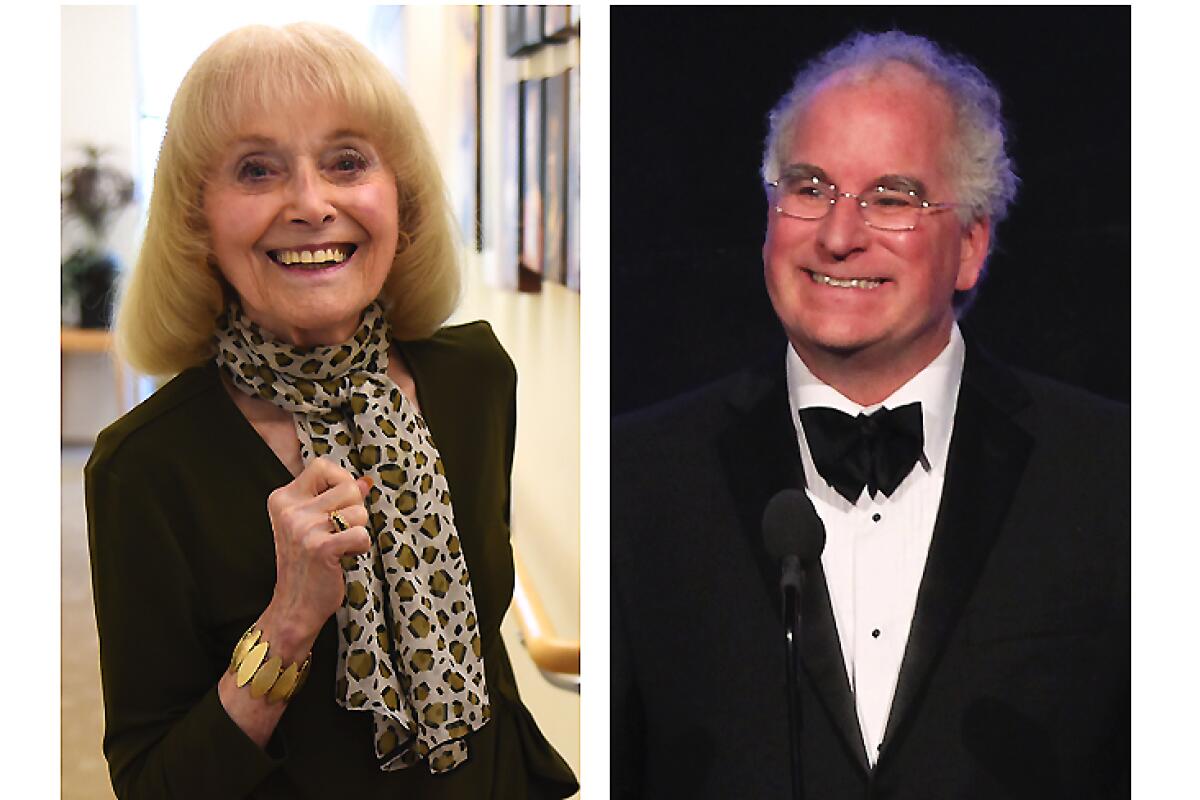

Lillian Michelson is Hollywood’s most famous and beloved librarian. Her marriage to late, great storyboard artist and production designer Harold Michelson brought her to Los Angeles in the late 1940s and eventually to Samuel Goldwyn Studios, where she began a lifelong career providing inspiration and information for all manner of filmmakers. Over the next half-century, she would build a cinematic research library second to none.

Six months ago that library seemed doomed to the dumpster.

After nearly six decades serving filmmakers first at Samuel Goldwyn, then the American Film Institute, Zoetrope Studio, Paramount and DreamWorks, the library filled 1,594 boxes: tens of thousands of books, photographs, magazines and a panoply of other visual resources. All of this had been sitting for five years in a storage facility, paid for by friends who could not bear to see it all destroyed.

Lillian spent those five years battling a shoulder injury, various ailments of age and, as of March 2020, the pandemic-forced lockdown of the Motion Picture & Television Fund community where she lives. Daniel Rain’s 2017 documentary “Harold and Lillian: A Hollywood Love Story” brought renewed attention to the couple (who were also immortalized on screen as the basis for King Harold and Queen Lillian in “Shrek”) and the collection. But as she entered her 90s, Lillian’s primary concern was not for her health but for her library. Many people had spent countless hours trying to find the collection a home, particularly Thomas Walsh, former president of the Art Directors Guild.

It was Walsh who contacted me, and I wrote a story about Lillian and her library in the hopes that someone somewhere would find a place for it.

Someone did.

Lillian Michelson inspired and informed thousands of filmmakers for more than six decades. Now her legendary research library sits in storage while she and her friends try to save it from becoming landfill.

Like Lillian Michelson, Brewster Kahle is a lifelong librarian. Unlike Lillian, he has worked almost entirely in the digital realm. Since graduating from MIT with a degree in computer science and engineering, he has focused on realizing one singular dream: to build a digital version of the famed Great Library of Alexandria.

Access to all knowledge, he says, was one of the early promises the internet made, though in the era of social media and the dark web, that is sometimes difficult to remember.

“Twenty-five years ago, we were promised the Library of Congress,” he says. “Instead we got Facebook.”

As with many digital pioneers, Kahle’s early career was a mix of misses, hits and sales — in 1999, he sold Alexa Internet, the web traffic analysis company he co-founded with Bruce Gilliat, to Amazon. (Amazon’s now-famous virtual assistant is named, in part, for that company, so every time you say “Alexa, find … ,” you are paying homage to Kahle’s Alexandrian dreams.)

Kahle began the Internet Archive in 1996, and that is where his heart lies. Although best known for its “Wayback Machine” feature, which allows universal access to old and defunct URLs (including some deleted tweets), the Internet Archive contains millions of books, texts, movies, TV shows, audio files, video games, software programs and billions of web pages.

When Kahle learned of Lillian’s plight, he decided her library would fit right in.

“We’ve started archiving entire libraries, some from colleges that no longer want to have a physical library,” he says. “A library is more than a collection of books and materials; it’s a reflection of the people who created it. It’s evidence of a community. We are building a library of libraries.”

But preservation is not the main point. Kahle wants people to use the Internet Archive as they would an actual library. That vision is not without its detractors. During the pandemic, the Internet Archive created what it called a National Emergency Library. By suspending the number of people who could borrow the more than 4 million books in its Open Library, the archive hoped to help schools and people affected by remote-learning issues and library closures. “How do you keep civilization going when your libraries are closed?” Kahle asks.

Not by giving them free access to copyrighted books, several publishing houses answered. Although almost 3 million of the Open Library books are in the public domain, the rest are not, which means they are subject to lending restrictions. Penguin, Random House, Hachette, HarperCollins and Wiley sued. The archive closed its National Emergency Library in mid-June, but the publishers did not drop the suit and now hope to close the Open Library entirely. The case, which is scheduled for a federal court trial in 2021, is seen by some as a test not just of digital enterprise but of the publishing industry’s control over what it means to own a book.

When film researcher Lillian Michelson was at DreamWorks Animation, she’d bring her husband, famed storyboard artist and Oscar-nominated production designer Harold Michelson, to work with her.

None of this should affect the Michelson collection, which Kahle sees as a bridge to innovators in the entertainment industry — and also a bit of a challenge.

“We want to make a digitized version that will aid the next generation,” he says. “I’m not a film librarian, so it’s new to me. The collection is scattershot and very visual. But I do know that in films, attention to detail is so important — and I worry that we have filmmakers just going to Google Images and getting away from actual archival history.”

Digitizing the library’s contents is not the problem; figuring out the most user-friendly interface system is. “I’m hoping that the film community will help us. No doubt we will get things wrong, and the thing that cannot be replaced is, obviously, Lillian. But I’m hoping the people who want to use it will help us improve it. And I think there will be all sorts of uses for it that we can’t imagine.”

Donations are, of course, appreciated; the Internet Archive is a nonprofit, and though Kahle says that the Michelson collection will be digitized in full no matter what, additional funding would help speed the process.

Lillian may not be able to solve interface problems, but she is thrilled that her work, which reflects and influenced the work of so many others, will be made available to anyone who needs it; a portion of the collection was unveiled on Thursday with a handy how-to-navigate tutorial.

“It is the perfect place, the perfect ending,” she said to me after first talking to Kahle about his plans. “I couldn’t be happier.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.