Is ex-L.A. County Sheriff Lee Baca, once one of the nation’s most powerful cops, headed to prison?

Lee Baca was never an easy man to define.

Throughout a remarkable, albeit flawed, career as sheriff of Los Angeles County, Baca defied tough-guy police stereotypes with an affectionate, oddball style of leadership that earned him the nickname “Sheriff Moonbeam.”

For the record:

7:20 p.m. July 18, 2016An earlier version of this story incorrectly said that Lee Baca had ceded day-to-day operations of the Sheriff’s Department to Merrick Bobb as well as to Undersheriff Paul Tanaka. As was mentioned in the story, Bobb was a monitor of the department for more than two decades and so was not ceded control over the agency.

He was at once admired for his progressive ideals and criticized for failing to put his thoughts into action. He succeeded in building ties with minority communities, promoted programs to rehabilitate inmates and pushed for more services to help homeless and mentally ill people.

But at the same time, many of the department’s deep-seated problems persisted or worsened under him.

The elusiveness that marked Baca’s time in office will meet hard reality Monday morning when he is sentenced in federal court for lying to federal authorities who were investigating attempts by sheriff’s officials to obstruct an FBI inquiry into abusive deputies working in county jails – an undeniable reckoning that will color his extensive career with disgrace.

“Here you had somebody who had good ideals and who, on several important issues, like homelessness and the mentally ill, seemed capable of sounding different and being more understanding,” said Merrick Bobb, who monitored the Sheriff’s Department for the county for more than two decades. “But after a while, all people will remember is that the sheriff resigned and pleaded guilty to a federal crime. Whatever else he did that was good will be lost.”

Bobb and others who worked closely with the sheriff criticized Baca for taking a detached approach to running the department and ceding control to Paul Tanaka, his undersheriff. Tanaka, who was sentenced last month to five years in prison, is one of several sheriff’s officials and deputies who have been convicted of playing roles in the scheme to obstruct the FBI.

Former L.A. County Sheriff Lee Baca admitted lying to federal prosecutors who questioned him about whether he was involved in attempts to obstruct an FBI investigation into the county jails. In this audio, assembled from a nearly four-hour recording

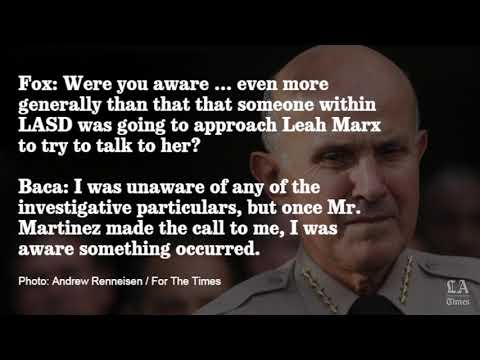

Baca, 74, admitted in February that he lied during a 2013 interview with investigators in which he maintained he knew little of the efforts by subordinates to thwart the FBI’s probe into the county jails. In fact, Baca conceded, he had known in advance of a plan to have deputies confront an FBI agent and threaten her with arrest. And he did not contest other allegations, including that he was aware an inmate working as an FBI informant had been hidden from agents. Baca retired months after the interview.

The admission came as part of a surprise plea deal with the U.S. attorney’s office that Baca struck after prosecutors made it clear to him that they were prepared to ask a grand jury to indict him on criminal charges.

Monday’s sentencing hearing in U.S. District Judge Percy Anderson’s downtown courtroom is expected to be more tense and dramatic than most as it remains an open question how much prison time, if any, Baca will serve.

Before sentencing Baca, Anderson must decide whether the terms of the plea deal Baca and prosecutors reached are acceptable. The agreement calls for Baca to receive no more than six months behind bars.

Anderson, who has dealt harsh punishments to Tanaka and the others caught up in the obstruction case, could decide six months in prison is too lenient. If he does, Baca would then have to choose between two unappealing options: Go ahead with the sentencing and accept whatever sentence Anderson has in mind, or withdraw his guilty plea and take his chances with charges the government might decide to bring.

The question of how Baca should be punished has grown more complicated in recent weeks after Assistant U.S. Atty. Brandon Fox and Baca’s attorney, Michael Zweiback, revealed in court filings that the former sheriff was in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Despite the diagnosis, Fox, who heads the public corruption and civil rights unit, argued to Anderson that Baca still should go to prison for six months.

The former sheriff’s cognitive impairment is “slight,” Fox wrote in court records, adding that there was no evidence Baca’s condition played a role in his lying to federal authorities. The lies came during an interview a year before Baca first consulted a doctor about “memory issues,” Fox wrote.

And although Fox conceded Baca did not play as direct a role in the obstruction as the others who have been convicted, a six-month sentence was necessary not only to punish him but to send a message that no one in law enforcement was above the law, even a popular elected official atop one of the country’s largest law enforcement agencies.

Zweiback did not deny his client’s misdeeds, writing in a court filing that Baca had “failed” the people he was elected to serve.

“His life’s work has ended in a large scale breakdown of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department at a time when he was its leader,” the attorney wrote.

But Zweiback implored Anderson to take into account the good Baca did in the Sheriff’s Department and spare him time in prison. It would be unjust, he said, to let Baca’s failures at the end of his career overshadow his accomplishments.

Among dozens of letters filed in support of Baca -- including ones from former California governors Gray Davis and Arnold Schwarzenegger, as well as former Mexican President Vicente Fox -- was one from an ex-inmate who took education and rehab classes in county jail and said his “life was forever changed by the forward thinking and vision of one man … Sheriff Lee Baca.”

Zweiback also raised concerns about whether Baca could receive appropriate medical care in a prison setting, saying his diagnosis of Alzheimer’s has left him in need of “consistent monitoring” and treatments that hope to slow the progress of the disease.

Prosecutors rebuffed the questions about Baca’s care with a declaration from a Bureau of Prisons medical director, who assured Anderson that Baca would be cared for adequately.

Whatever the sentence, the sight of Baca standing before Anderson and being tagged as a felon will serve as an epilogue few could have anticipated during the 15 years Baca ran the Sheriff’s Department.

“I always thought of Baca as the anti-sheriff – thoughtful, philosophical, someone who cared as much about prevention as traditional policing,” said Fernando Guerra, who heads the Center for the Study of Los Angeles at Loyola Marymount University. “It’s still a shock for me to think that he got caught up in this.”

To be sure, Baca never followed any conventional playbook for law enforcement leaders.

A rail-thin man who rarely carried a sidearm, Baca often greeted other men at public events with a kiss on the cheek and a hug.

In 2005, with Compton in the grips of a spasm of gang violence and homicides on a near-record pace, he sent deputies door-to-door in the city to deliver letters inviting gang members and their parents to meet with the sheriff to discuss the “ramifications” of their “decision-making process.”

And determined to reform inmates during their time in his county jails, Baca created programs for drug addicts, domestic abusers and the mentally ill. He also launched a corporate-style training program for his deputies to tap employees’ potential.

Baca’s unorthodox style and endeavors left many inside the department grumbling that he cared more about social work than police work – a charge the sheriff said he wore with pride.

And in many ways, it was an attitude ahead of its time. The hard work Baca put in to make the department more inclusive and build ties with minority communities has become standard for police chiefs and sheriffs.

But there was no shortage of outright failures and missteps.

I always thought of Baca as the anti-sheriff – thoughtful, philosophical, someone who cared as much about prevention as traditional policing.

— Fernando Guerra, Center for the Study of Los Angeles at Loyola Marymount University.

He was initially defiant in the face of allegations that inmates were being beaten, even though internal department memos had raised concerns about deputies meting out “jailhouse justice.”

He came under fire for releasing thousands of inmates early, some of whom went on to commit violent crimes.

Baca blamed budget cuts that he said gave him little choice but to close portions of his jails and freeze deputy hiring. Still, he drew worldwide notoriety in 2007 when he released hotel heiress Paris Hilton early from jail.

In 2010, the Sheriff’s Department hired nearly 300 officers from a little-known county police force, including some who had accidentally fired their weapons, had sex at work and solicited prostitutes. Nearly 100 had issues with dishonesty, including lying or falsifying police records, according to documents review by The Times.

Baca said his top aide at the time was responsible for the hires.

Baca also traveled the world relentlessly, making trips to Pakistan, Jordan and Europe to discuss international terrorism and other issues only tangentially related to the job of a sheriff.

The wanderlust was a symptom of a larger shortcoming, said a former county official who worked closely with Baca for many years and considers him a friend.

“Lee’s biggest problem was that he saw himself as more than sheriff to L.A., he really thought of himself as a sheriff to the world. He didn’t take care of the work he needed to do here,” the former official said.

It was a flaw that ultimately led to Baca’s downfall as the distracted sheriff increasingly ceded control of the day-to-day operations to Tanaka, said Guerra and others.

“There was always the worry that when you have a philosopher king in charge that the people below him will run roughshod,” Guerra said. “Now, whenever I give a lecture to students about Lee Baca, the first thing I’ll have to say is, ‘This is how it ended.’”

For more news from the federal courts in Southern California, follow me on Twitter: @joelrubin

ALSO

Fresno police break ranks with other departments by releasing shooting video from body cameras

LAPD will increase patrols, 911 screenings in wake of violence against police officers, mayor says

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.