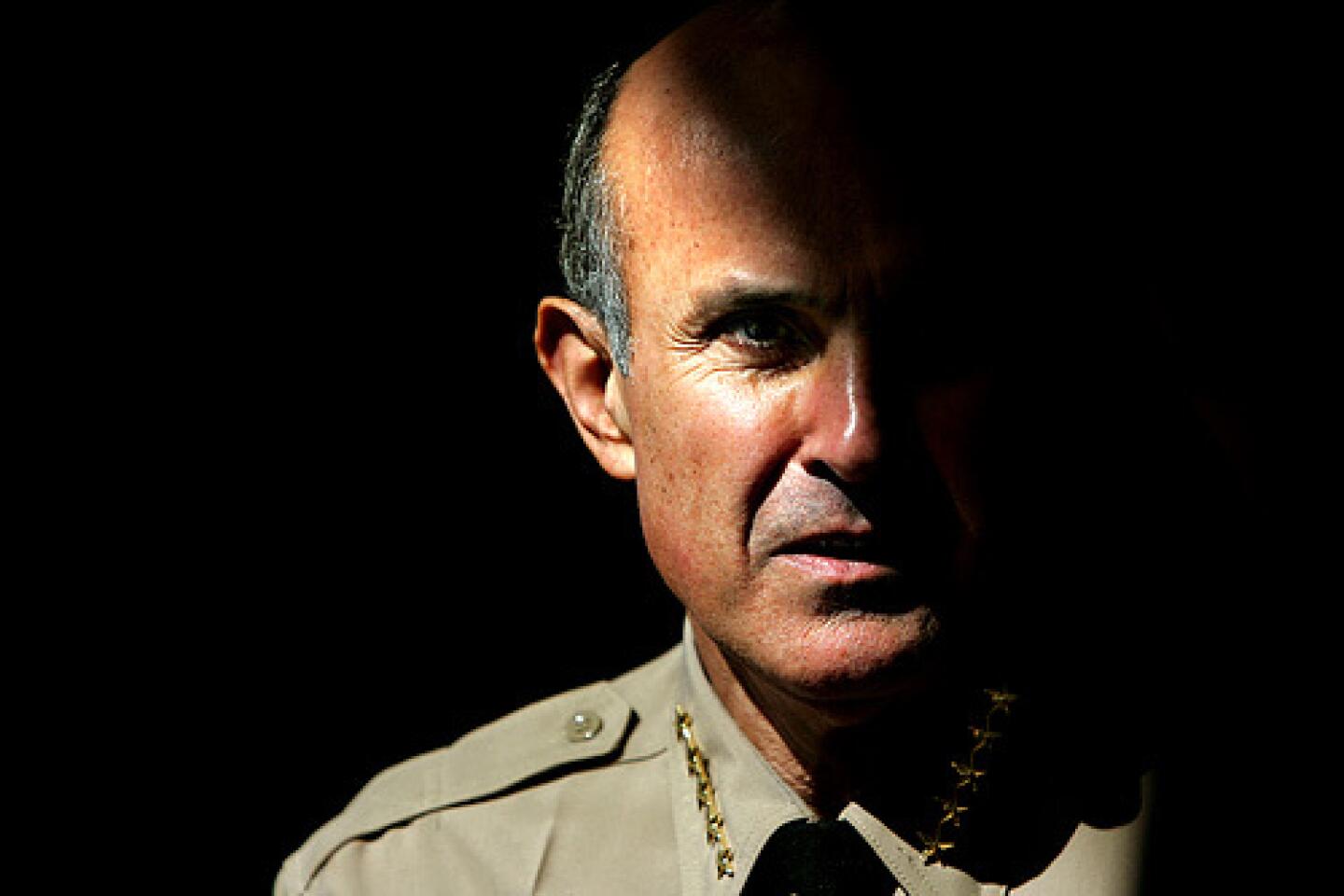

A Quirky Sheriff Who’s on the Move, Out in Front and Feeling Some Heat

With gang violence soaring and homicides on a near-record pace in Compton last year, Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca sent deputies door-to-door in the community.

They were not there to make arrests.

They were delivering letters inviting gang members and their parents to meet with the sheriff to discuss the “ramifications” of their “decision-making process.”

On the day of the meeting, Baca waited patiently at the Compton courthouse.

But no gang members showed up — just three of their relatives. Two dozen deputies milled around, some rolling their eyes and grumbling about wasted time.

Only Baca seemed perplexed by the turnout.

In his seven years at the helm of the nation’s largest sheriff’s department, Baca’s quirky, innovative approach to crime fighting has endeared him to those who traditionally mistrust the police and made him one of the county’s most successful politicians.

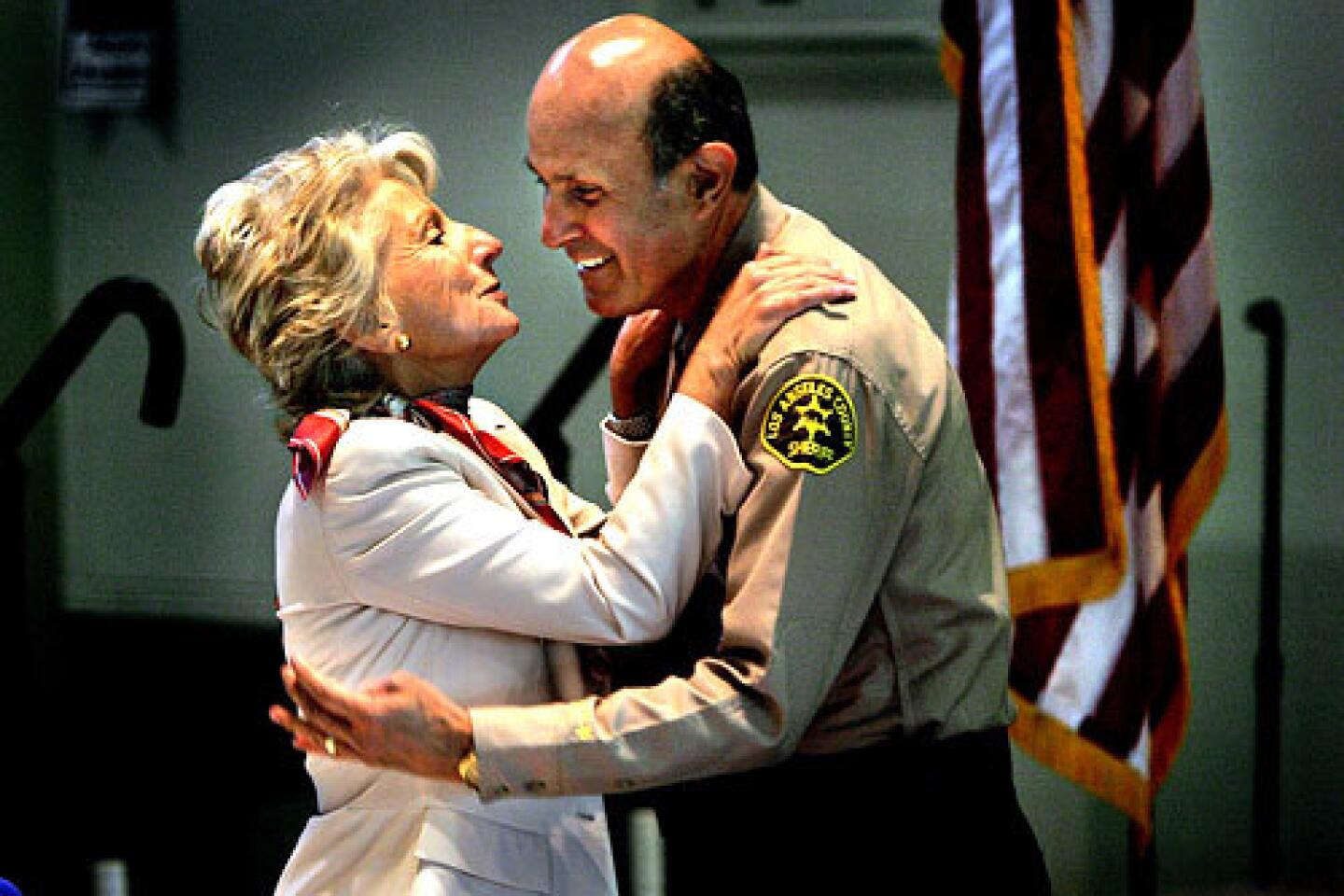

He has tirelessly wooed the ethnic and religious groups that make up his potent power base. Despite four challengers, he is expected to win a third term so easily on June 6 that he has not sought endorsements or campaigned actively.

But within law enforcement — where he is sometimes referred to derisively as “Sheriff Moonbeam” — many see him as an ineffectual manager ill-equipped to lead his vast organization out of the deep troubles it faces.

High attrition and low morale pervade his 8,000-officer force, charged with the Herculean tasks of policing 2.7 million people over an area of more than 3,000 square miles as well as guarding 18,000 increasingly violent inmates in America’s biggest jail system.

Between 2002 and 2005, as the city of Los Angeles experienced a significant drop in homicides and other major crimes, homicides rose by nearly 20% in sheriff’s territories.

The Sheriff’s Department continues to reel from painful budget cuts ordered by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors four years ago. To avoid taking deputies off patrol, Baca imposed a hiring freeze, shut his training academy and closed jails.

Baca’s options were limited. His remedies, however, have left his department short by as many as 1,000 deputies and forced the early release of a flood of offenders, back on the streets because the sheriff no longer had the capacity to house them.

As his overstretched officers have struggled to cope, Baca often has focused on the county’s social ills and being its ambassador to the world.

He has attended six international conferences in the last nine months alone. Last November, when reports surfaced that an inmate had been beaten to death at Men’s Central Jail, he was in Jordan discussing terrorism with King Abdullah.

Throughout his tenure, issues of judgment have dogged Baca, many of them involving the use of his authority to benefit friends or backers.

Though he is among the highest-paid elected officials in the country, earning more than $285,000 in 2005, Baca has accepted more than $42,000 in gifts since taking office, including some from those who do business with his department. In 2004, he took more gifts than California’s other 57 sheriffs combined, according to state financial disclosure forms.

He accepts political contributions from his employees as well, and has promoted those who have worked for or donated to his campaigns.

Despite near-constant budget pressure, Baca also has hired a cadre of civilian advisors and put one of his closest friends on the payroll as a $105,000-a-year advisor.

In recent weeks, Baca has faced criticism for allowing a group of local businessmen — many of them campaign donors — to call themselves his Homeland Security Support Unit and carry ID cards similar to those of department employees. After the matter triggered inquiries by county and state officials, the Sheriff’s Department recalled cards issued to more than 4,000 department volunteers.

During a recent interview, Baca sat at a conference table in his Monterey Park headquarters and reviewed his tenure. Over the course of a meandering eight-hour conversation, he said he was not concerned about the appearance of impropriety but with doing what was best for his department. He insisted that he has the agency on course and that no one understands its needs better than he.

“Many people in my position, they don’t operate with vision. They operate with polls,” he said. “I’m not thinking about getting elected. I’m the sheriff of Los Angeles County.”

New Age Sheriff

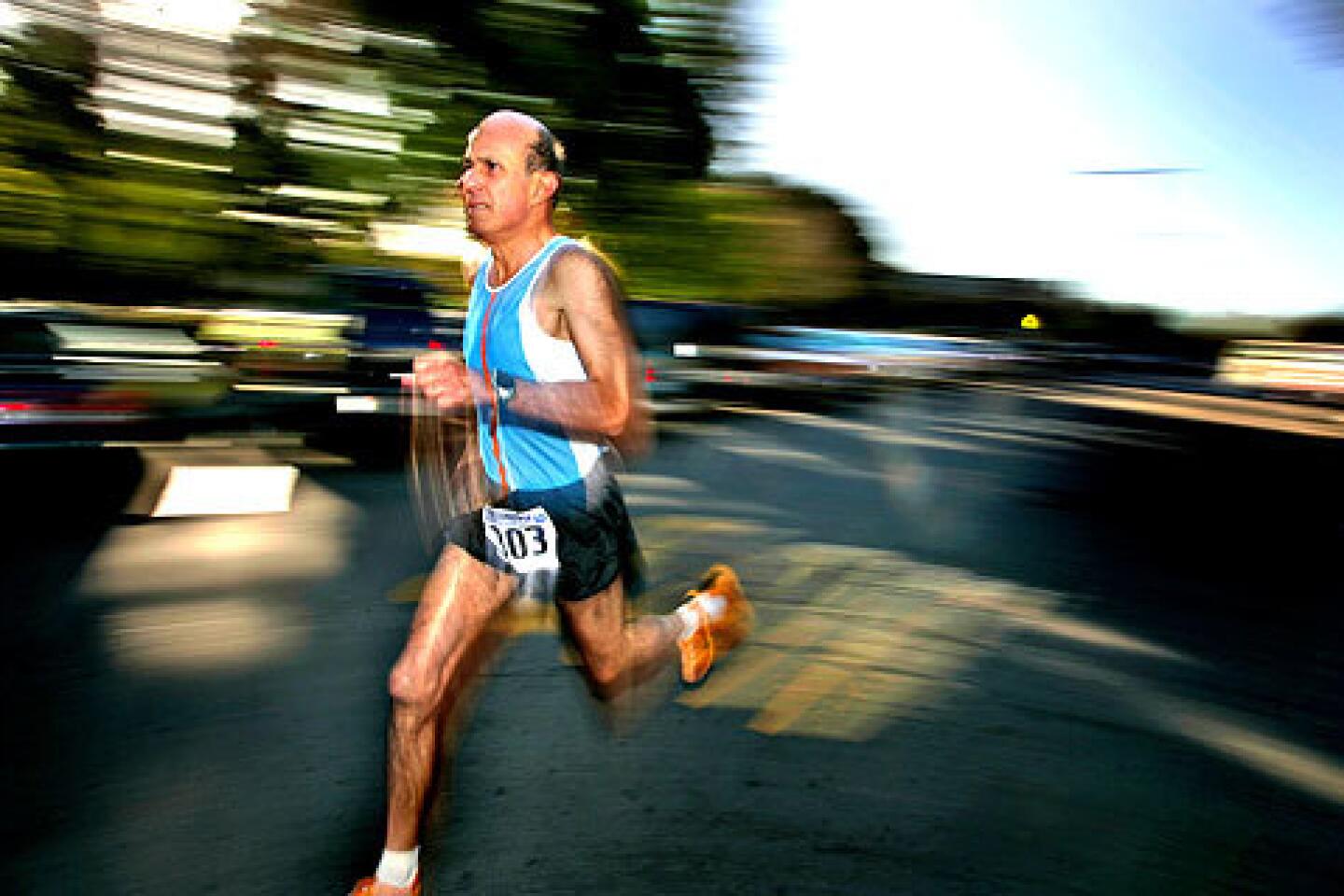

Leroy D. Baca is the least typical of lawmen.Tall, with a sinewy runner’s build, the county’s top cop rarely wears a gun on his hip and calls the National Rifle Assn. a “political bully.”

Once a community college dropout, he earned a doctorate in public administration from USC at age 51.

Baca’s musings on law enforcement frequently leave listeners befuddled. Asked about whether it made sense for the department to take on additional contracts, he quoted Sir Robert Peel, founder of London’s Metropolitan Police Force, who said, “The people are the police, and the police are the people.”

When interviewed on video recently by the Church of Scientology for the annual L. Ron Hubbard birthday celebration, he spoke of the positive influence Hubbard’s teachings have had. (Hubbard died 20 years ago.)

“It was the right thing to do,” he said. “The people that are Scientologists are trying to do good.”

Baca, 64, grew up in East Los Angeles, raised by his paternal grandparents after his parents’ divorce. He shared a bedroom with his disabled uncle Willie, whom he often helped bathe and dress.

The early lesson in compassion made a deep impression. Open in his affections, Baca often kisses male friends on the cheek and tells them he loves them. During the final illness of former Undersheriff William Stonich’s father, Baca sat at the elderly man’s bedside for hours, holding his hand.

Baca joined the Sheriff’s Department in 1965, after a stint in a Culver City oven factory. At the plant, he befriended Mel Block, whose brother, Sherman, was then a sheriff’s sergeant. Sherman Block went on to become sheriff. Baca, who revered Block as a mentor, followed him up the ranks.

His 1998 bid to take Block’s place, however, set off a bitter, divisive battle. County sheriffs typically had anointed their successors. Many assumed that Block — a four-time incumbent who was in failing health — would not run again. Once he decided to do so, he saw Baca’s candidacy as a betrayal. Tension built until Baca resigned as division chief, saying in a 2002 deposition that Block had threatened to demote him and “cut my legs off.”

Baca did well enough in the primary to force a runoff. The campaign took a strange turn when Block died of a cerebral hemorrhage days before the general election in November. Baca won comfortably, with 61% of the vote.

He inherited a sprawling, complex organization beset with problems. The department had earned a reputation for racism and sexism, as well as for being unresponsive to the public and county leaders. It had come under fire for financial mismanagement. Racial violence simmered in its jails.

Baca’s early years brought a whirlwind of new initiatives.

To the surprise of those long frustrated by the department’s secretive culture, he partnered with the county to create the Office of Independent Review, inviting half a dozen civil rights attorneys to monitor internal investigations of officer misconduct.

Intent on using county jail time to turn around inmates’ lives, Baca created programs for drug addicts, domestic abusers and the mentally ill. He set up the Deputy Leadership Institute, a corporate-style training program, to tap employees’ potential.

Baca also expanded his department’s territory, taking on contracts to police the city of Compton and to provide security for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and nine campuses in the Los Angeles Community College District.

Traditionalists called the contracts ill-conceived empire-building and argued that Baca’s programs siphoned money from core functions. They said he was turning his officers into social workers. Baca took it as a compliment.

“Whoever said that all police work was arresting people?” he said. “I’ve widened the job of what my people can do to solve human needs.”

A Turning Point

Perhaps the defining moment of Baca’s stewardship came when the Sheriff’s Department was swept up in a countywide budget crisis.Until then, the sheriff had spent freely — in 2001, he had exceeded his $1.5-billion budget by $25 million, prompting rebukes from the Board of Supervisors.

In fiscal 2003 and 2004, he was forced to reduce spending by more than $80 million a year, a devastating prospect no matter how the cuts were implemented.

Calling it a “last resort,” Baca chose to eliminate thousands of jail beds, releasing criminals who had served as little as 10% of their sentences, in order to avoid layoffs and preserve the number of deputies patrolling the streets.

“None of us thought it was the right thing to do,” he said. But, he concluded, it was the best choice available.

Others in law enforcement said Baca should have made do with fewer patrol cars or taken on the deputies union and replaced some sworn officers with cheaper civilian labor for jail duty. They said he hung on to pet programs, such as a special unit to help inmates transition into life on the outside, at the expense of more fundamental areas.

“I’d give him an ‘F’ grade,” Tom Higgins, head deputy of the district attorney’s central complaint division, said of the way Baca led his agency through tough times. “The core function of the sheriff is to protect the public from today’s crime and today’s criminal. It just seems as if he was in over his head.”

Avoidable or not, Baca’s choices have had a deep impact on his department and may continue to affect it for years to come. By the end of a three-year hiring freeze, the department had dropped from a peak of just under 9,000 sworn officers to just over 8,000.

Working conditions suffered as officers throughout the department were forced to work extensive overtime.

In another blow to morale, the freeze meant that deputies — given the unpopular assignment of guard duty in the jails at the start of their careers — were stuck there an average of five to seven years instead of two to four.

A year ago, after the Board of Supervisors allocated additional funds, the department resumed hiring but could barely outpace attrition. At least 80 deputies left for other law enforcement agencies in 2004-05, many of them lured away by police departments in places where they could afford to buy homes.

“Ten years ago, the vast majority of deputy sheriffs would say, ‘Come here. It’s a great career. You have endless opportunities,’ ” said Steve Remige, president of the union that represents more than 7,000 deputy sheriffs and district attorney investigators. “I haven’t seen that recently.”

Last month, Remige’s union endorsed retired Capt. Ken Masse, one of Baca’s opponents in the coming election. Baca won the backing of less than 10% of the 1,300 members who voted.

Baca called the endorsement “an act of mischief” by the union’s board, insisting that he had broad support among his agency’s rank and file.

“I have my hand on the pulse of this organization,” he said. “I know what deputies feel more than the union knows, more than any one of my captains or commanders know . I know when they’re hurting. I know when they’re happy . I have a tremendous amount of radar internally in the Sheriff’s Department.”

Baca said his biggest accomplishment as sheriff has been increasing public trust in his department, making it more open and more accountable for its officers’ actions.

“He’s in the avant-garde,” Undersheriff Larry Waldie said. Even the executive director of the ACLU of Southern California praises Baca as a “humanitarian.”

It’s unclear, however, how much Baca’s ideas have trickled down.

“He is a problem-solver and a civic change agent,” said civil rights attorney Constance L. Rice, who has been a campaign advisor to Baca and considers him a friend. “He’s got a very recalcitrant culture, and there’s a lot of work to be done to change it below him.”

Most who scrutinize the department say it has become more adept at managing public fallout in times of crisis, most notably last year, when Baca was credited with defusing a volatile situation in Compton.

Deputies had pursued an SUV into a residential neighborhood, then fired 120 rounds at it, hitting nearby homes, injuring the driver and wounding an officer caught in the crossfire. The sheriff swiftly issued an apology. He went to Compton to face residents’ ire and disciplined the deputies involved.

But his deft handling could not remove the sting from two independent reviews, one of which called the incident “the perfect storm of blunders, mistakes, forgotten or nonexistent training, disobedience, poor supervision, and lack of planning and foresight.”

Said Luis Carrillo, a South Pasadena attorney who handles lawsuits alleging officer misconduct: “Baca is a slick politician. He knows what buttons to push.

“But in the streets the brutality and the abuse continues.”

A Man on the Go

It was raw and dark as the sheriff set off on his predawn run through Hyde Park. He had recently arrived in London to attend a three-day anti-terrorism conference. Jet lag and the winter chill could not dampen his mood.“Good morning!” he bellowed exuberantly to startled passersby, a bright streak in his lemon-yellow parka.

Knocking off seven miles, he lay down on the floor of the hotel lobby and, oblivious to discreet stares from the staff, did several hundred abdominal crunches.

Baca is in perpetual motion, determined to be the sheriff 24-7. “No one,” he likes to boast, “works harder than me.”

Baca’s schedule more closely mirrors that of a big-city mayor than a county department head. His calendar is full of political endorsement meetings and community appearances. Even on weekends, Baca can be found posing for photos with Miss Chinatown or attending an Armenian Jewelers Assn. gala.

He travels more than any sheriff in California, although less than Los Angeles Police Chief William J. Bratton. Calling himself the county’s “voice of public safety,” Baca also sees it as part of his job to lobby for his department with state and national leaders, and to share his ideas with the world.

According to his calendar, he spent 63 days traveling last year, making almost a dozen trips to Sacramento and Washington, D.C. He also took a series of trips abroad, going to Guatemala to talk with the president and the police, meeting with officials on police accountability at The Hague and attending a conference in Moscow titled “Promoting Civil Society.”

Baca said his trips were usually brief and that, with his staff in place, there was no leadership vacuum in his absence. Still, his tendency to focus on social causes and to manage from afar prompted San Dimas Councilman Sandy McHenry to wonder if the sheriff’s attention had strayed.

“In the end, you’re a law enforcement agency, and your job is to maximize the safety of the area you serve,” said McHenry, whose city contracts with the sheriff for law enforcement services. “I just think sometimes there needs to be an attention to detail and focus.”

Most of Baca’s international trips have not been at taxpayer expense. He visited Amman, for example, as a guest of the Jordanian government.

The county paid for portions of Baca’s January trip to London. Much of the material turned out to be familiar. He spent hours, for example, at a session on the well-known “broken windows” approach to policing.

Still, Baca came away elated. The first night, he had dined on beef in mushroom sauce at a banquet hosted by Scotland Yard. The second, he had his picture taken with a guard outside Buckingham Palace. The relationships he built with the British police were invaluable, he said. “I got the maximum exposure for the least amount of time,” he said. “I leave with the phone numbers of the top law enforcement officials in the country.”

‘It’s Like Chicken Soup’

By his own account, Baca acts with little regard for potential conflicts of interest or the appearance of favoritism. He is quick to embrace ventures, sometimes before thoroughly vetting them.He recently endorsed a proposal for a Santa Clarita Valley drug treatment center even though its operators’ presentations — based on the teachings of Scientology founder Hubbard — were labeled “not based on science” by an official with the Los Angeles Unified School District. A 2005 state report concluded that the group’s drug-prevention program failed to “reflect accurate, widely accepted medical and scientific evidence.”

Baca wrote to county planning officials, urging them to approve the project. He later said he had not known about the clinic’s treatment regimen, which includes long saunas and high doses of niacin, but defended it as legitimate.

Earlier this year, Baca set aside his staff’s proposal to seek competitive bids and insisted that the department restart an inmate counseling program operated by retired football great Jim Brown’s Amer-I-Can Foundation. The group was awarded a new contract — worth as much as $300,000 a year — even though auditors concluded Amer-I-Can may not have provided all of the services for which the department had already paid $1.3 million.

“No one knows what these jails need better than I do,” Baca said, calling Amer-I-Can’s program unique.

Since taking office, Baca has accepted thousands of dollars’ worth of meals, travel and sports tickets, as well as 71 rounds of golf. Among those who have picked up his golf tab: actor Michael Douglas and Dr. Gary Alter, a sex-change specialist featured on the television show “Dr. 90210.”

Baca drew a distinction between the gifts he accepts and the gratuities that he and his officers are prohibited from taking from those they serve. People gave him gifts out of concern for his welfare, not to buy access or influence, he said.

“They think I need to gain weight with all the food,” he said, adding that he gives much of it to his staff. “They think that I’m stressed out. ‘You need to golf.’ It’s like chicken soup. I mean this sincerely.”

The sheriff accepted $14,000 in wedding gifts when he married his second wife, Carol Chiang, in 1999. Among them was $1,000 in cash from Horacio Vignali and his wife. Vignali was a wealthy entrepreneur who had made a fortune in auto body shops, real estate and other ventures.

Baca later wrote a letter vouching for Vignali to President Clinton, who was then considering a request to commute the prison sentence of Vignali’s son, Carlos, a convicted drug dealer. Clinton granted the son clemency. Baca acknowledged trying to help Vignali but said he did less than what Vignali had wanted.

“He wasn’t happy with that letter. I told him, ‘This is the best I can do. I can vouch for you. But I can’t vouch for your son,’ ” Baca said.

Baca’s benefactors include people whose companies have done business with the Sheriff’s Department, including self-help guru Lou Tice, officials with the Commerce Casino, and Chuck Reed, an executive with Aon Corp., an insurance, consulting and risk-management business. Aon has been paid more than $1 million in fees by the Sheriff’s Department.

Reed, who said he considers Baca a “dear friend,” has given the sheriff 10 rounds of golf, taken him to USC football games and bought him meals. A vice president for Aon’s insurance operation, Reed said he was not aware until told by a reporter that the Sheriff’s Department had hired Aon to develop a system for screening applicants for promotions. Baca said he didn’t know about Aon’s work for the department either.

“I’ve never done a dime’s worth of business with the sheriff,” Reed said. He praised Baca’s kindness. “You can tell a lot about a guy on the golf course. Lee Baca never loses his temper. If he has a bad shot, he doesn’t throw clubs. He’s a gentleman. And a gentle man.”

In addition to gifts, Baca has accepted support from those who work for him, taking in more than $70,000 in political contributions from department employees, records show.

“I didn’t ask for it, I don’t need it, but I sure appreciate it,” he said. “It shocks me actually. I didn’t know they felt that strong about me. I’m not an easy guy to work for.”

As sheriff, Baca has sole discretion over high-level promotions. When Baca took office, there were 90 officers in the department who held ranks of captain or above. Baca has since promoted 40 of them. Of those who gave to his campaigns for sheriff, 73% received promotions, before or after the donations. Of those who did not contribute, 26% received promotions.

At least nine Sheriff’s Department employees played central roles in Baca’s first campaign, meeting in a Pasadena real estate agent’s office to strategize and help their future boss prepare for speeches.

He has promoted eight of them. Two, Paul Tanaka and Doyle Campbell, were lieutenants in 1998. They each have been promoted four times and are now assistant sheriffs.

Baca said he did not track who had made contributions and had never promised promotions in exchange for political support.

“The public outside is not concerned about this stuff,” he said.

A Search for Tax Dollars

Since the budget crunch, Baca has invested his political capital mostly toward one goal: persuading county leaders and voters to funnel more tax dollars into his department.He campaigned hard in 2004 for Measure A, which would have raised the sales tax a half-cent to fund law enforcement. It fell short, but the sheriff has not given up. He is working to get a quarter-cent sales tax increase and a $500-million bond measure for jail improvements on future ballots.

Yet even as he seeks more money, he has found resources to hire a contingent of civilian advisors with roles that defy easy definition.

Baca employs three field deputies, each paid more than $88,000 a year, who perform such tasks as writing promotional articles to tout sheriff’s programs, organizing prayer breakfasts and helping issue credentials to visiting foreign dignitaries.

One, Jeffrey Prang, is a councilman in West Hollywood, where the sheriff holds a contract to provide police services. Another, Bishop Edward Turner, is a well-known pastor with the Power of Love Christian Fellowship in South Los Angeles. The third, Tevan Aroustamian, is an Iranian emigre well-connected in the county’s Middle Eastern community. Baca, referring to the trio as a “potpourri,” said their primary value was in bridging the gap between the department and communities reluctant to trust police.

“One’s a gay guy. One’s a black minister,” Baca said, referring to Prang and Turner, respectively. “It speaks to the people of this county.”

Last year, Baca hired a close friend, Michael Yamaki, to be his special advisor. A former criminal defense attorney who served as former Gov. Gray Davis’ appointments secretary, Yamaki has known Baca for 15 years and lent him $20,000 during his 1998 campaign.

His role at the Sheriff’s Department is still evolving. Yamaki said he had negotiated a deal for local businesses to allow sheriff’s vehicles to use their parking lots in emergencies and advised Baca and his staff on matters such as state legislation and how to handle area judges.

Baca said Yamaki’s connections and savvy would help the department bring in additional county and state money, far outweighing his $105,000 salary.

“He’s a very political guy,” said the sheriff. He dismissed concerns that Yamaki and the other aides were a luxury.

Earlier this year, Yamaki accompanied the sheriff on his trip to London, traveling at county expense. After returning, he submitted an expense claim asking the county to reimburse him $136 for four dinners, even though he had not paid for any of them. The London police paid for one. A Times reporter paid for another.

Yamaki said the clerical staffers who prepared his expense report mistakenly thought county employees traveling on business were entitled to a per diem. In fact, county policy allows employees to be reimbursed up to $10.50 for breakfast, $13.50 for lunch and $34 for dinner, but only for meals they actually pay for, Auditor-Controller J. Tyler McCauley said.

“That would mean I’m in trouble,” Yamaki said.

His gaffe revealed a long-standing practice by sheriff’s employees. Between 1999 and 2005, seven other department executives — Baca included — requested reimbursement of $11,800 for 675 meals. In nearly every case, they requested the maximum amount, sometimes expensing meals while attending conferences that included them. They are not required to submit receipts.

Yamaki said he intends to return his meal money. Baca said the county meals policy was vague.

“That seems petty to me,” he said of questions concerning the expense claims.

No Looking Back

With Latino and black inmates squaring off for a seventh day of rioting in the Los Angeles County jails earlier this year, Baca announced he would bring in Cardinal Roger Mahony and other religious leaders, hoping they could appeal to inmates’ “common good as human beings.”Much like his Compton intervention, however, the step proved ineffective. When the melee stretched across two weeks, county officials and prison advocates alike were reminded that the jails remain much as they were when Baca first became sheriff.

Baca maintains he is making incremental progress. With the county’s financial picture improving, the sheriff received a $150-million budget increase in the current fiscal year and is expected to get a $128-million boost next year. After stumbling at first, the agency’s recruitment push has finally reached full speed. Baca said the agency would add 100 deputies every five weeks until the end of the year.

Asked what he would change about his time in office, Baca responded that he was “not a retroactive thinker” and that he was confident that the public trusts him, even if it does not always agree with him.

He shrugged off the skepticism he has faced inside the department as an inevitable side effect of change.

“I work the folks in this organization really hard. That’s what leadership is about. And there will be times they’ll like me more than at other times, I’m sure,” he said. “The key is that I stay abreast of my effectiveness by saying to every member of the Sheriff’s Department that you work extremely hard and I love that fact. And you do it from your heart.

“But you won’t work harder than me. You need vacations. I don’t. You need days off. I don’t. You need to rest. I don’t. I’m 64. I’ll run faster than you.”

Staff researcher Maloy Moore contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.