Newsletter

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The sun started to rise, bathing the Sierra Nevada in a red glow that I had seen only in postcards until then. I leaned in silence against Mt. Whitney’s granite rock face, taking in the view soon after finishing a series of 99 grueling switchbacks.

During that roughly two-mile stretch, I was giddy. Maybe I was light-headed from the altitude like my hiking partner, but I like to think it was euphoria. I was so focused on what I was doing as I made my way up the tallest peak in the Lower 48 for the first time, I hadn’t allowed myself much time to think or feel.

The significance that my first summit was taking place where my older brother completed his last really hit me at that point. I started to feel. Intensely.

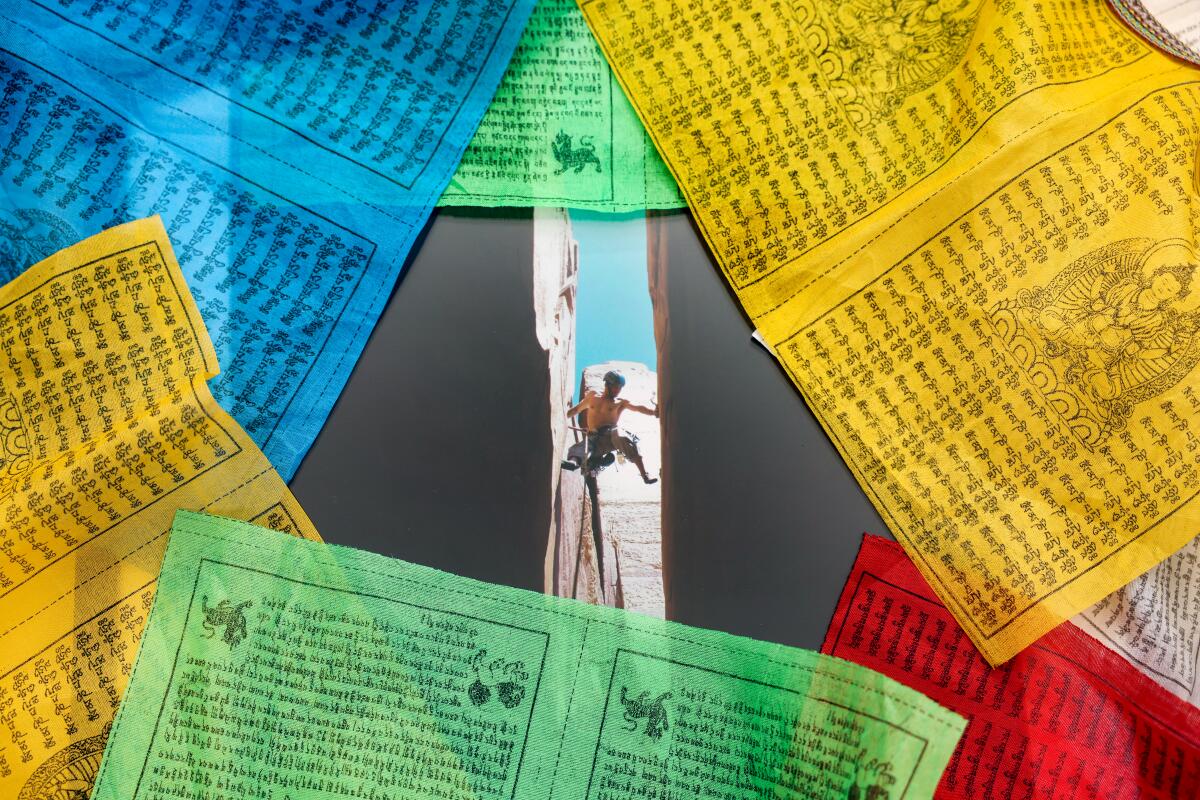

On June 30, 2012, my brother, Michael Ybarra, died in a climbing accident at the northern edge of Yosemite National Park. Mike was the extreme sports correspondent for the Wall Street Journal and previously worked for the Los Angeles Times. Mike started climbing in his mid-30s. He threw himself into his newfound passion with a dedication and discipline that was typical Mike.

My desire to hike Mt. Whitney on what would have been his 55th birthday, Sept. 28, 2021, lived vaguely in the back of my mind for a while. I had no idea how to accomplish this task. I’d never done a big hike, certainly not anything that required the type of endurance Mt. Whitney demands. But I was determined.

Our parents divorced when we were young, so my siblings and I formed a deep bond. Older by a few years, Mike was an inspiration to me — intellectually gifted and intrepid. His unexpected death left me without an anchor that once steadied me. I coped by immersing myself in the outdoors, a place Mike had loved. It made me feel closer to him and brought solace. As did hiking Mt. Whitney, despite the challenges.

The final 1.9 miles was hellish terrain. I was so tired by this point that I kept twisting my ankles on uneven rocks. It had been windy and sunless, the trail very narrow. Along this particularly perilous section, I wondered if anyone had ever slipped and fallen to their death. One to two people die on Mt. Whitney on average every year, after all.

After a spinal cord injury left him paralyzed, Jack Ryan Greener centered his life on a quest to hike Mt. Whitney. When the time came to try, the quest proved perilous.

I knew my brother also had faced fear during his climbing career. From “Climbing Alone, Risking It All,” a Wall Street Journal article he wrote about free soloing because he couldn’t find a partner: “I started climbing down, gripping the crack like it was the only thing standing between me and eternity — which it was. My eyes scoured the blank rock for the tiniest rugosity onto which I could plant a foot. I was acutely aware that each move could be my last.”

Gathering my fledgling mountaineering skills, I scrambled up to the summit. It took 11 hours and as many months of training to reach 14,505 feet.

Before the hike, I expected that once at the summit, thoughts of Mike and his time here would wash over me. But the hike had been so strenuous that, if anything, it taught me the meaning of being in the moment. Once at the top, I wasn’t ruminating on Mike’s absence but on how relieved I was that I had finally made it.

I also understood the sense of accomplishment Mike felt from climbing. The summit was smaller than I had imagined, almost like a little island perched atop valleys dotted with lakes and mountains washed in shades of beige and gray. Clouds that looked as if they had been painted in broad white brushstrokes marked the soft blue sky. I was gazing over the American West, in all its stark and vast beauty.

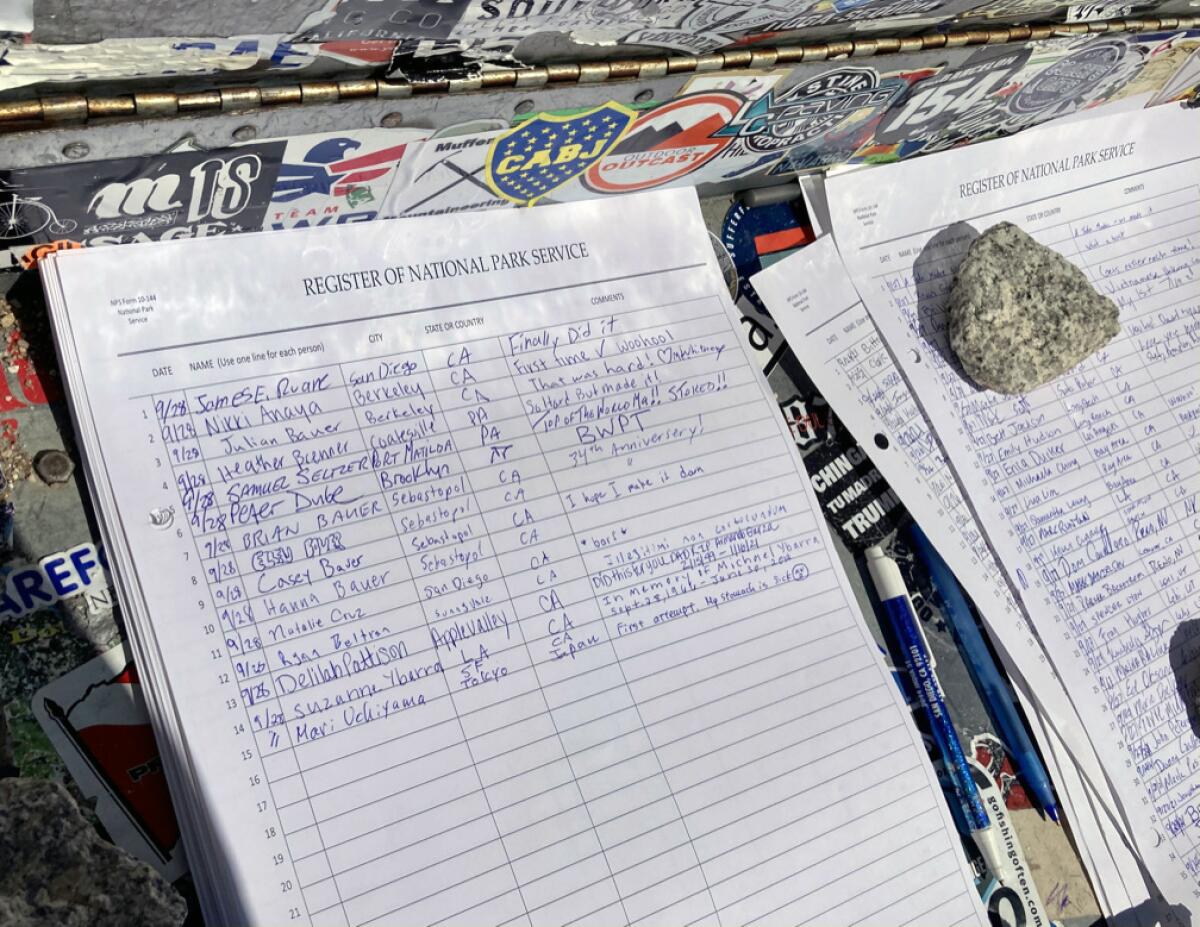

In the summit registry at the top, tucked away in a metal box that was leaning against a stone hut built over 110 years ago by astronomers, I wrote, “In Memory of Michael Ybarra Sept. 28, 1966-June 30, 2012.” After I finished my inscription, I photographed it from numerous angles, trying to get the clearest image. I wanted to show it to my 88-year-old dad who had accompanied me to Lone Pine, the town nearest the trailhead for Mt. Whitney.

Feeling guilty for taking so long, I apologized to the group behind me. I explained that I did the hike in memory of my brother who died and that it was his birthday. A woman in the group, her face obscured by sunglasses and winter gear, said she understood because she had ascended Mt. Whitney in memory of her father, who had died in January. She mentioned that her brothers had also previously passed. “I’m happy to be here,” she said. I felt an instant connection to this faceless woman. Her entry also marked her loss: “Delilah Patterson, Apple Valley, CA. Did this for you Dad RIP. Armando Garza 2/15/49-1/16/21.”

If you’re applying for a permit to hike Mt. Whitney and wonder how to prepare, here are training peaks you need to know.

Delilah was hiking with her friend, Paula. Surprisingly, she had a day permit to hike Mt. Whitney the previous fall, as had my hiking partner, Mari Uchiyama, who is married to Mike’s first climbing partner and close friend, Eric Gafner. Both trips had been canceled due to a fire in the area.

“We cried a couple of times today — it was emotional,” Paula said. It felt serendipitous that we were all there that day.

Mike and his friend Marissa Christman had spent what would be his last week alive climbing in the Eastern Sierra. They climbed the east face of Mt. Whitney mere days before he died.

“We actually went there to climb a route on [nearby] Mt. Russell. Whitney was a snap decision before we left the same day,” Marissa told me in an email.

I realized my dream to hike Mt. Whitney could become real once another one of Mike’s former climbing partners, Misha Logvinov, told me there were numerous routes up, including one that doesn’t require mountaineering skills. After that, the pieces started falling into place.

One day, Mari messaged me on Instagram about how she wanted to hike Mt. Whitney. I couldn’t believe my luck. Even better, my brother’s first Mt. Whitney attempt had been with Eric in January 2006, so it seemed right that I would team up with his wife. Eric and Mike had to snowshoe for part of their unsuccessful ascent.

“The trail was buried so we were sort of figuring out the route as we went using a map. Mike fell through the snow once and got caught in a tree. You could see the ground around 15 feet below,” Eric texted me. “We knew we were the only fools on the mountain because the snowshoe and ski tracks all stopped after the first half-mile. We never made it [to the summit], but had a blast.”

With the right conditioning plan, trekking to tallest mountain peak in the Lower 48 is more attainable than you think.

Mari and I started the hike up Mt. Whitney with the glimpse of a shooting star. Then, as I ascended, I understood, bit by bit, what Mike had seen and felt in the mountains. I experienced a part of his life I hadn’t before, saw what he saw, walked where he walked.

I felt happy at the summit, something I hadn’t expected. On my brother’s birthday, I am usually consumed by sadness, wishing I could see him one more time to say goodbye. Atop Mt. Whitney, maybe I did get to say goodbye after all.

Mt. Whitney Trail Info

Trail length: 22 miles

Trailhead elevation: 8,330 feet

Summit elevation: 14,505 feet

Elevation gain: About 6,175 feet

Hiking permits per day: Roughly 195 from May 1 to Nov. 1

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.