This story is part of Image’s May issue, Homemaking, about home and the many ways we choose to make it.

The laundromat is the perfect place to cry in public.

I’m here now, crying as I type this. I don’t care who sees me. I’m tucked away into one of the two-person benches between the silver three-load washers, tears welling up in my eyes near their tipping point. I make eye contact with a man who passes me by on his way to the sink. He looks slightly concerned. But even if I wasn’t partially hidden it wouldn’t matter. I feel safe here. It’s a place that puts intimacy on a rush order, past the point of faux social etiquette. I’m surrounded by people who see the color of my underwear as I pull it out of the dryer. What are a few tears at this point? We’re already well acquainted.

I’ve always been too internal for my own good. I cry in public often because of what’s happening in my imagination. And the laundromat — its familiar, sterile smell of cleaning products and metal, the constant chugging sound of water and hot air — is a place that feels particularly primed for me to slip into my subconscious mind, like sliding into a comfortable pool of Jell-O. I remember things I forgot. I romanticize the Krypto Villain stickers in the quarter vending machines. I sit and stare at people until it hurts. I fantasize about what their lives are like, or all the times they wore those nice faded jeans that they’re pulling out of the dryer while the static shocks their skin. I see a couple sitting under the food tent outside. Their knees point into each other’s while they’re eating, and by their body language alone I conclude that they are, of course, in love. I see a teenage boy shadow-boxing the washing machine in what I decide by a demeanor that I find all too familiar, is a bid for attention. I’m reminded of when I was 14 and needed attention.

The dryer whirs soft, the fluffy smell of chemical flora rises, the badass little kids with silver teeth run circles around their mom while she folds their Spiderman T-shirts. An image flashes in my mind of myself when I was small — curly hair, dirty Osirises and the fake tattoos I got from the quarter machine fading on my forearm, using the laundry cart like a bumper car or laying my head on a freshly baked mountain of clothes that was just piled into it from the dryer.

From Vivienne Westwood “SEX” chokers to John Galliano-era Dior logo rings, the list in this vintage archive goes on, and it goes deep.

I love the laundromat. I’ll tell anyone who will listen. You will catch me at a party giving what might as well be a PowerPoint presentation about the joys of the laundromat. What most people see as an undesirable chore I see as a comfort zone. My own private version of the club, where fluorescent light floods from the ceiling and there’s always Amy Winehouse or Salt-N-Pepa playing over the loudspeaker. My local laundromat is open 24 hours — as all the good ones are — and any time of day or night, for the rest of my life, I know there is a place that is open and waiting for me (as long as I have a hoodie to wash). I’ve never had an in-unit washer and dryer in my many years of living on my own. And it never mattered. Because I have something rarer, more special: a home away from home.

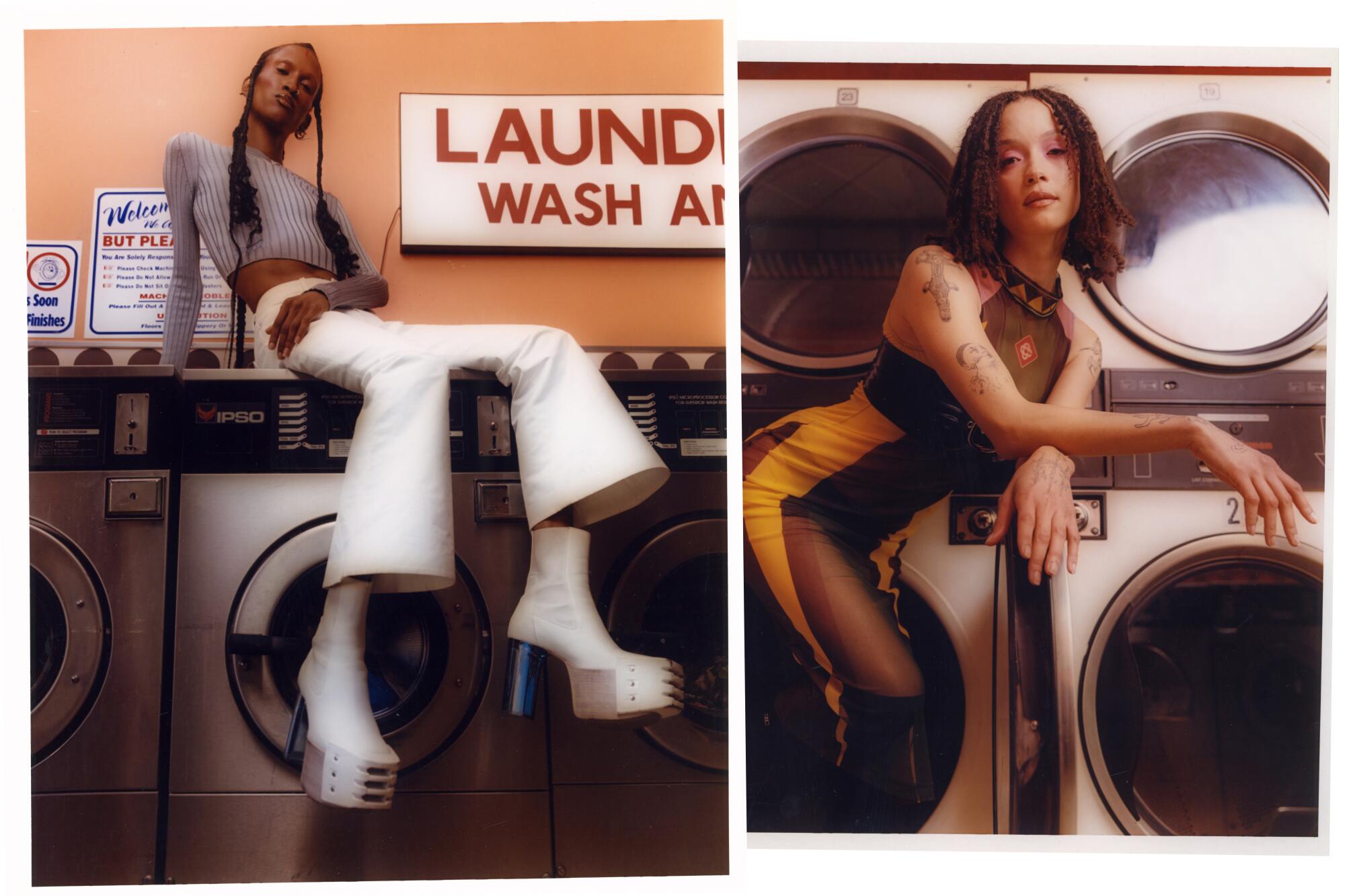

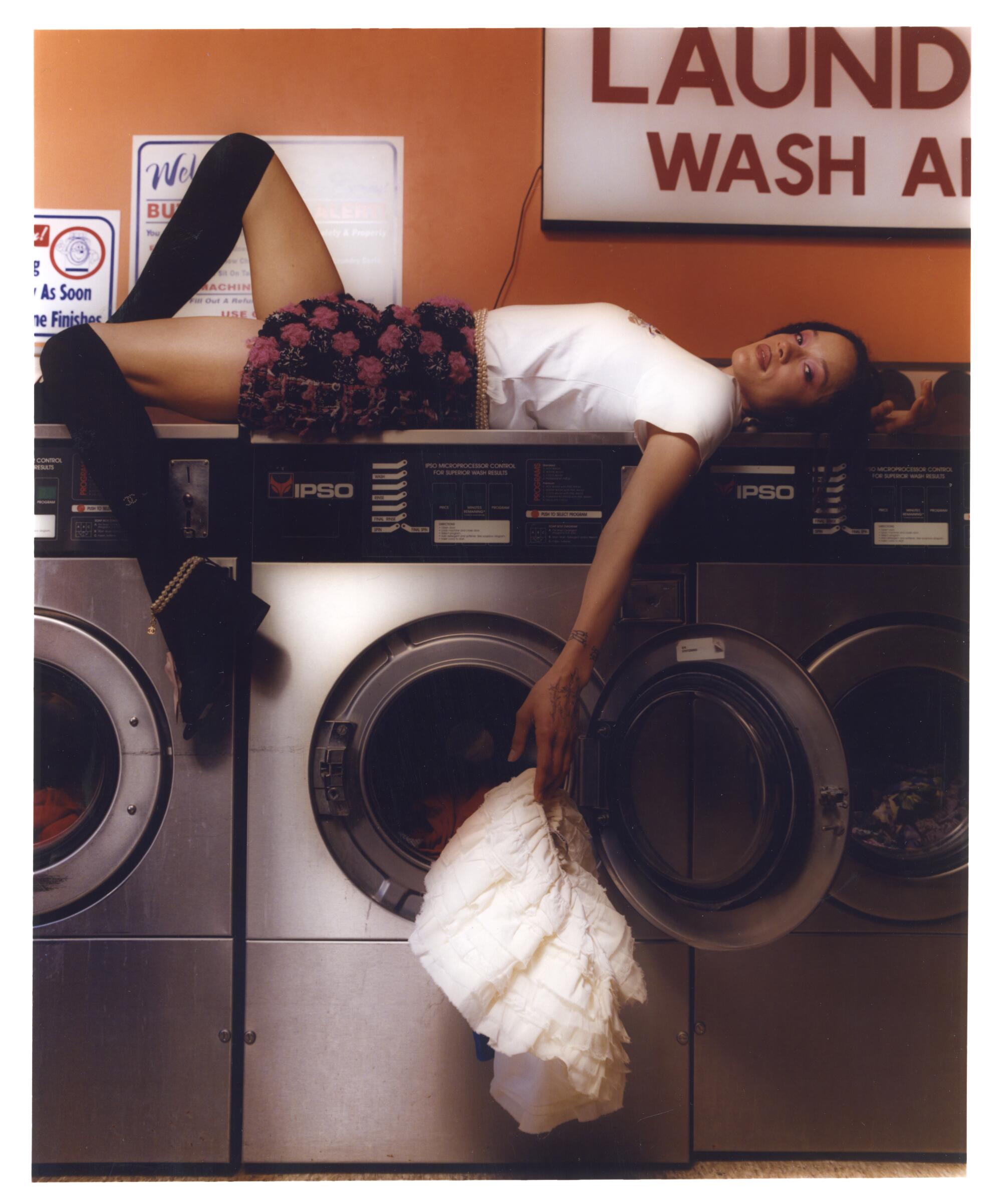

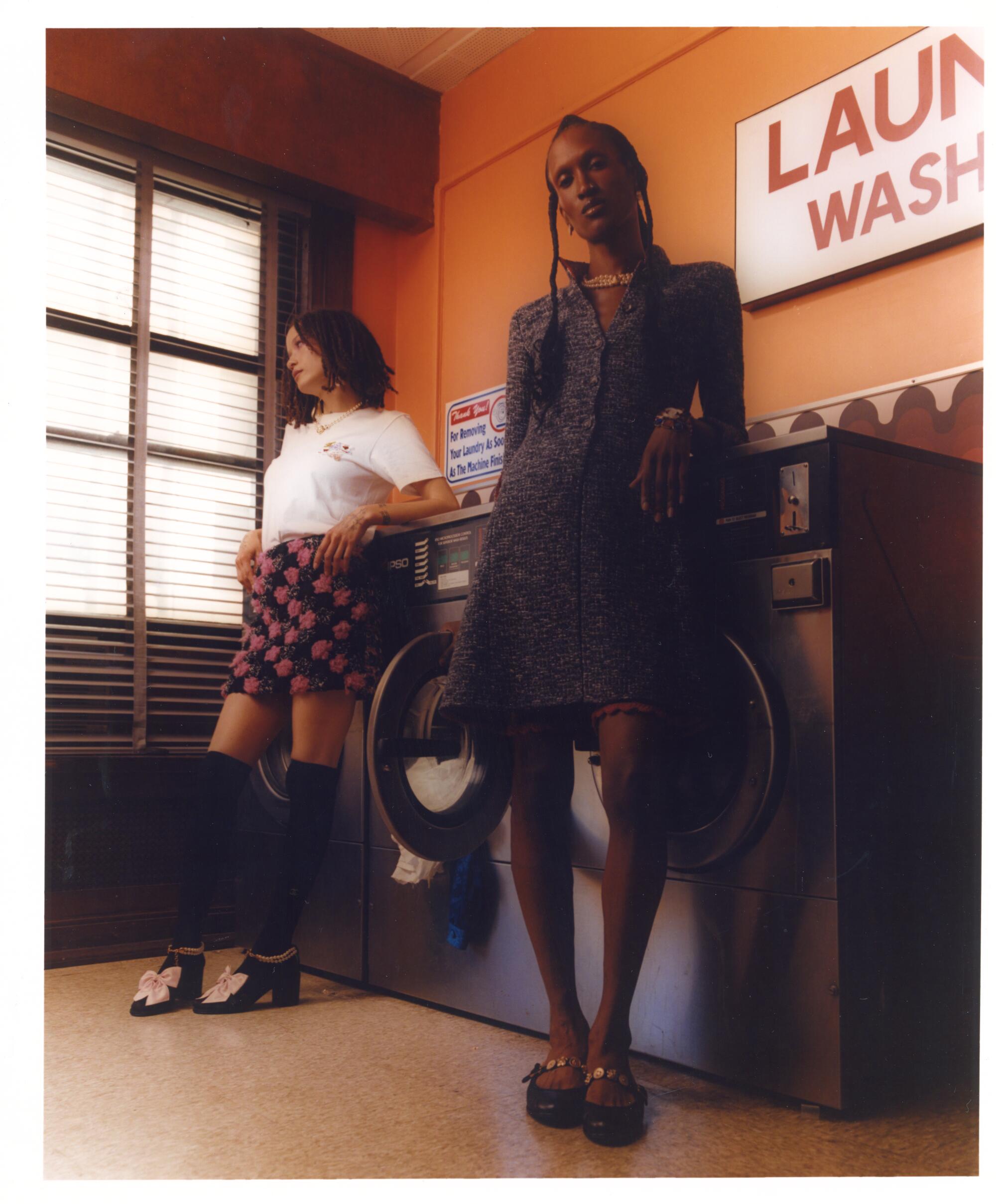

May wears Marni dress, Fendi pink boots.

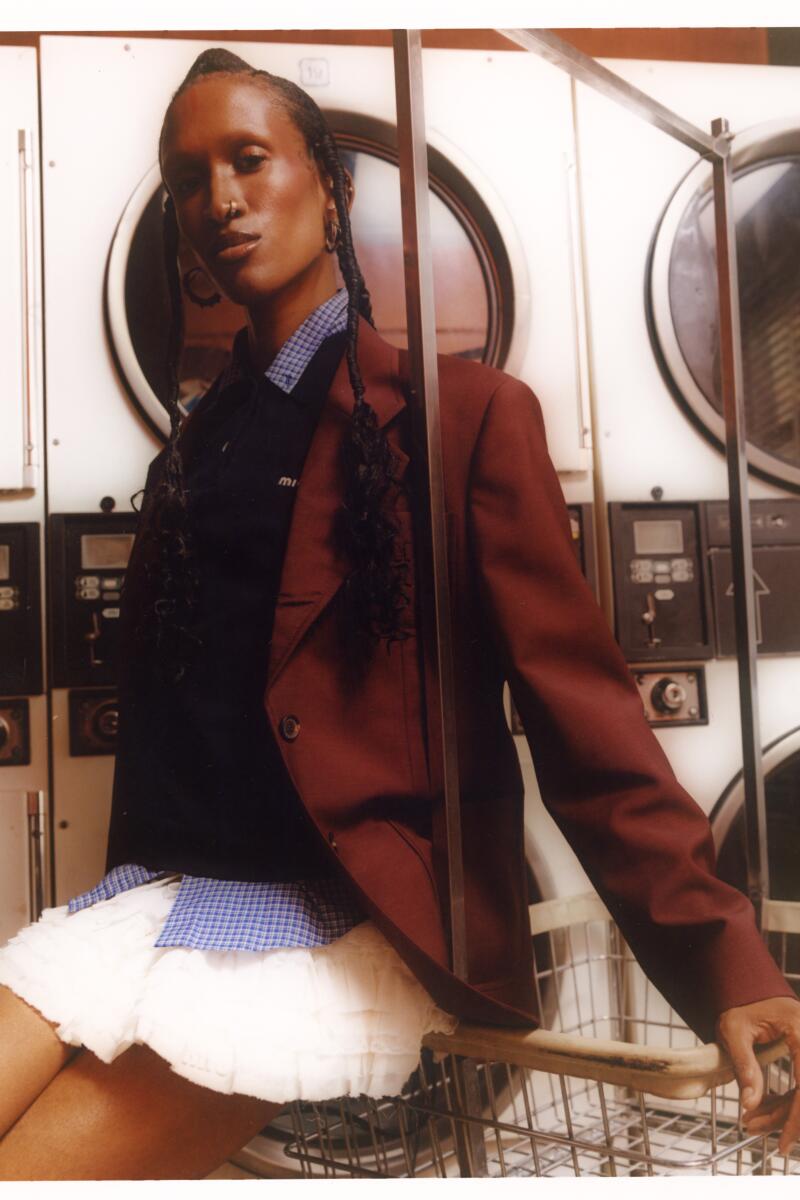

Maahleek wears Miu Miu, model’s own jewelry.

There’ve been rumblings on the internet lately about “third places” — spots people go to that are not their house, not their office, but a secret third thing. “These places are vanishing!” the TikTok feed will warn. Sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the term “third place” in his 1989 book “The Great Good Place” and expanded on it in his 2001 book, “Celebrating the Third Place.” Oldenburg’s life’s work has been dedicated to explaining why informal gathering spaces matter, and in his writing he defined some characteristics of a true third place, including low barrier to entry, being a status leveler, somewhere that conversations happen and arguably most importantly, being a home away from home. This, Oldenburg writes, is the antidote to isolation, the lubricant of a healthy social balance. “Y’all got nowhere to hangout and it shows,” stated one TikTok creator, who made a series out of suggesting third places.

The experience of the laundromat spills beyond the confines of its walls into its surrounding areas. If you’re doing laundry in a neighborhood like mine, then you’re very lucky, and every single day there is someone selling food on the sidewalk out front. Last time I was there, it was the new-to-me Colombian spot, a Mexican empanada spot and a birria spot that sells it on top of pizza. The smell of soupy, red meat mixing with the unmistakable perfume of Suavitel and Zote shavings. On the weekends in winter, you’ll find the champurrado lady selling Styrofoam cups of the viscous, steaming drink out of the trunk of her minivan.

The multidisciplinary artist recognizes something in a bag that’s always been present in his personal style: utility.

The parking lot is where all the good things happen. When I was in my early 20s, I used to put my load in and s**** a b**** with my bestie as I waited for the cycle to finish. It’s where I bought someone’s physical mixtape a couple months ago because I’m a recovering people-pleaser, and was in partial system shock from even seeing a physical mixtape. It’s where I can never find parking — even on a weekday evening — because as long as there are days to live there will be laundry to do.

The number of activities done there that have nothing to do with washing your clothes feels specific, in a lot of ways, to L.A. We do all of our photo shoots for our merch brands at laundromats (who among us?), throw experimental punk shows, come up with our best ideas. In my Notes app earlier this year I wrote: “Laundromat culture — places of business and life and love and food.”

I saw a post about a guy who lived in a renovated laundromat in Queens, which felt right to me — something to aspire to. In “The Great Good Place,” Oldenburg writes that third places should inspire the same fuzzy, warm glow of belonging as its inhabitants might find in their own homes. There should be a sense of ownership, of taking up space. I remember this when I Zelle the guy with the Colombian hat $6 for two potato and cheese empanadas. As I sit outside to eat them I notice a parked car with the driver and passenger seats reclined all the way back, two people with their feet up on the dash hold hands as they engage in a romantic, mutual endless scroll on their phones. “That’s beautiful,” I think. We make ourselves at home in places where we need to pass time. We find ways to be comfortable, to turn it into our living room.

When my mom comes to visit me she always takes a load of my laundry to wash at the laundromat I’m at now. (Yes, I’m 29, but her love language is “acts of service,” so sue me.) Every time, she comes back upstairs to my apartment with freshly folded T-shirts (and a blouse she shouldn’t have put in the dryer but did anyway) and regales me with a new story of an hourlong conversation she had with a stranger — the latest in her laundromat saga. I’m more the observant type. The interactions I usually have here are swift, but I still find them deeply meaningful. I notice a lady selling intricate gold-plated rings on one of the tables by the window, the natural light bouncing off the metal tray as the afternoon sun makes its descent. I ask her about them. All of these little moments fill me with the feeling of being human. There is so much talk about a need for connection, a need for community, but no one wants to spend an hour of their week philosophizing intense beauty in the mundane at their local laundromat, do they? That’s what I thought.

An important part of the laundromat experience is the massage chair. It’s the only spot that offers a soft surface to sit inside the actual building, and treating oneself feels right in a place like this. I sit in it long enough before it yells at me to put money in — I never get the actual massage, of course. I get up and relocate to a spot where I can watch the meticulous dance of a big family folding their clothes. They always have, like, 15 kids and 10 loads of laundry — an assembly line that communicates: We ain’t new to this. They quickly take up an entire counter and move with accuracy. I see one family bring a mega Tupperware container filled with hangers, attaching each of their nice button-up shirts like clockwork. It’s hypnotizing. I spot a long chartreuse dress with a flower detail that I would never wear but am deeply intrigued by. In the background, there are moments of intensity that bubble up and dissipate — a rush will be interspersed with serene moments — mimicking the flow of anything else in life.

And as soon as I slipped too deep, I’m jolted back to reality by two women arguing over a dryer, which is a normal interaction here. It went on for 15 minutes, each one of them throwing strays long after the initial confrontation was finished. Draaaaama, I thought. And I laugh to myself. Because that’s what happens when you’re comfortable, when you’re at home, when you’re with your family.

Production: Mere Studios

Models: Maahleek, May Daniels

Makeup: Selena Ruiz

Hair: Adrian Arredondo

Photo Assistant: Dillon Padgett

Styling Assistant: Deirdre Marcial