Mike had me cornered. He’d graduated ages ago, but his tastes hadn’t. He still went to high school house parties to drool over girls who read Sassy and got their braces tightened every four weeks.

“Hey,” he said to my padded bra.

“Hey,” I grumbled back.

Adulthood had given Mike a power he was eager to exploit; he could buy alcohol legally. Since my underage friends and I relied on people like Mike to supply us with Boone’s Strawberry Hill, we used caution around them. Mocking these losers could endanger our access to saccharine wines. It also could endanger us.

Mike gestured at my face with his half-empty bottle of Zima and asked, “Anyone ever told you you look like Buh-Jork?”

“You mean … Björk?”

Mike ignored my correction, instead asking, “What are you? You’re so … exotic.” He rambled on about Buh-jork’s “kind-of-Asian-hotness” until friends came to my rescue.

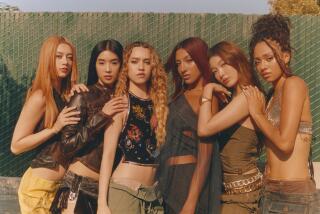

I confess this embarrassing Gen X memory as a gesture of solidarity. Many multiracial ladies of a certain age were similarly fetishized by their local Mikes, and for those of us perceived as embodying a certain type of racial ambiguity, being flirtatiously likened to Buh-jork was a collective rite of passage in the 1990s. Gross guys stereotyped us, casting us as orientalized, manic pixie dream girls.

When One Little Indian and Elektra Entertainment released Björk Guðmundsdóttir’s international debut solo album in July 1993, the world went bonkers for the record. “Debut” introduced the 28-year-old Icelandic musician to millions of fans, but some of us already admired her; that’s why we knew how not to butcher her name. We were kids who listened to the Sugarcubes, the alternative rock band for which Björk sung and pounded the keyboard. Released in 1992, “Stick Around for Joy” became the Sugarcubes’ third and final album, and it had given me “Hit,” a melodramatic song perfect for channeling my sophomoric woes. I was in awe of the way Björk growled the exasperated lyric, “This wasn’t supposed to happen,” and I adopted those five words as my own, growling the verse when I got Fs on French quizzes or popped ripe zits too close to the bathroom mirror.

Among those smitten with “Debut” was Spike Jonze, an instrumental figure in the history of California skateboard culture. Jonze’s passion for documenting street skating led him to filmmaking, and he became a leading music video director whose easily identifiable style, one that married the indie with the chic, shaped the visual aesthetics of the ’90s and early aughts. In 1995, Detour Magazine sent Jonze to the Chateau Marmont to photograph Björk. Five years prior, the storied French Gothic castle perched high on Sunset Boulevard had changed hands, coming under new ownership. Hotelier André Balazs subjected his acquisition to a facelift that erased much of its gritty and dilapidated charm. Tattered curtains, matted carpets and missing shower heads were replaced. A gym was installed in the attic. After witnessing its restoration, former It girl Eve Babitz, a Chateau regular, lamented, “I couldn’t imagine wanting to commit suicide here anymore.”

The two-hour Detour shoot happened the day before Jonze and Björk would begin working on the iconic video for the single “It’s Oh So Quiet,” and the mountain of photographs that they created together revives some of the Chateau’s former mystique. Björk and Jonze made use of the hotel’s interiors and pool, and the results are imbued with a sense of otherworldly glee that tells me the pair probably had a damn good time making art together. The results also present Björk’s beauty and intelligence as hers, not ours to devour. This self-possession is apparent in one of the six photographs published as part of Detour’s 1995 music issue. In it, the singer aggressively winks at the camera, reminiscent of a pirate. She withholds much of her body, especially skin, from the lens. Her pose forces the viewer’s eyes to her face, drawing attention to her eye. We peek at Björk, but the voyeurism is mutual.

Decades after the Chateau shoot, the fashion designer and creative director Humberto Leon discovered a trove of outtakes while helping Jonze to organize his archive. The two had met in 2004, when Jason Schwartzman introduced Jonze to Leon at a Christmas party, and the pair quickly developed a close bond, becoming one another’s artistic sounding boards. The pictures struck a nostalgic chord in Leon, a longing for the subcultural days of yore, and after proposing to Jonze that he exhibit at Arroz and Fun, Leon’s restaurant and gallery space in Lincoln Heights, the two decided to display 25 of Jonze’s never-before-seen photographs at the space (the show opens Feb. 15 and will remain on view through May). For die-hard fans unable to make it to Lincoln Heights, Jonze also is releasing “The Day I Met Björk,” a free downloadable zine through WeTransfer. A limited supply of physical copies will be sold at the gallery.

Often, when a male photographer shoots an ingenue in a hotel room, she winds up on the bed in a come-hither pose not found in the wild. Think Britney Spears’ first Rolling Stone cover shot by David LaChapelle, the one where the teen is wearing lingerie, holding a phone to her ear and cradling a Teletubby. It is pure Lolita. Instead of invoking such motifs, Jonze’s bedroom shots of Björk are goofy girl slumber party, the kind my friends and I had. Wrapped in white sheets, the singer transforms into a joyful poltergeist hopping on the bed, reminding me of the time that I jumped so hard on my bed, it broke. This incurred my father’s wrath but here’s the thing: Sometimes pissing off your dad is worth it. Björk’s other bedroom photo, the one where she wears an orange button-down blouse and sits at the foot of the bed, holding a white coffee cup to her lips, reminds me of the morning after our teen slumber parties. Recovery from our revelry required that we sip Alka-Seltzer and wolf down menudo.

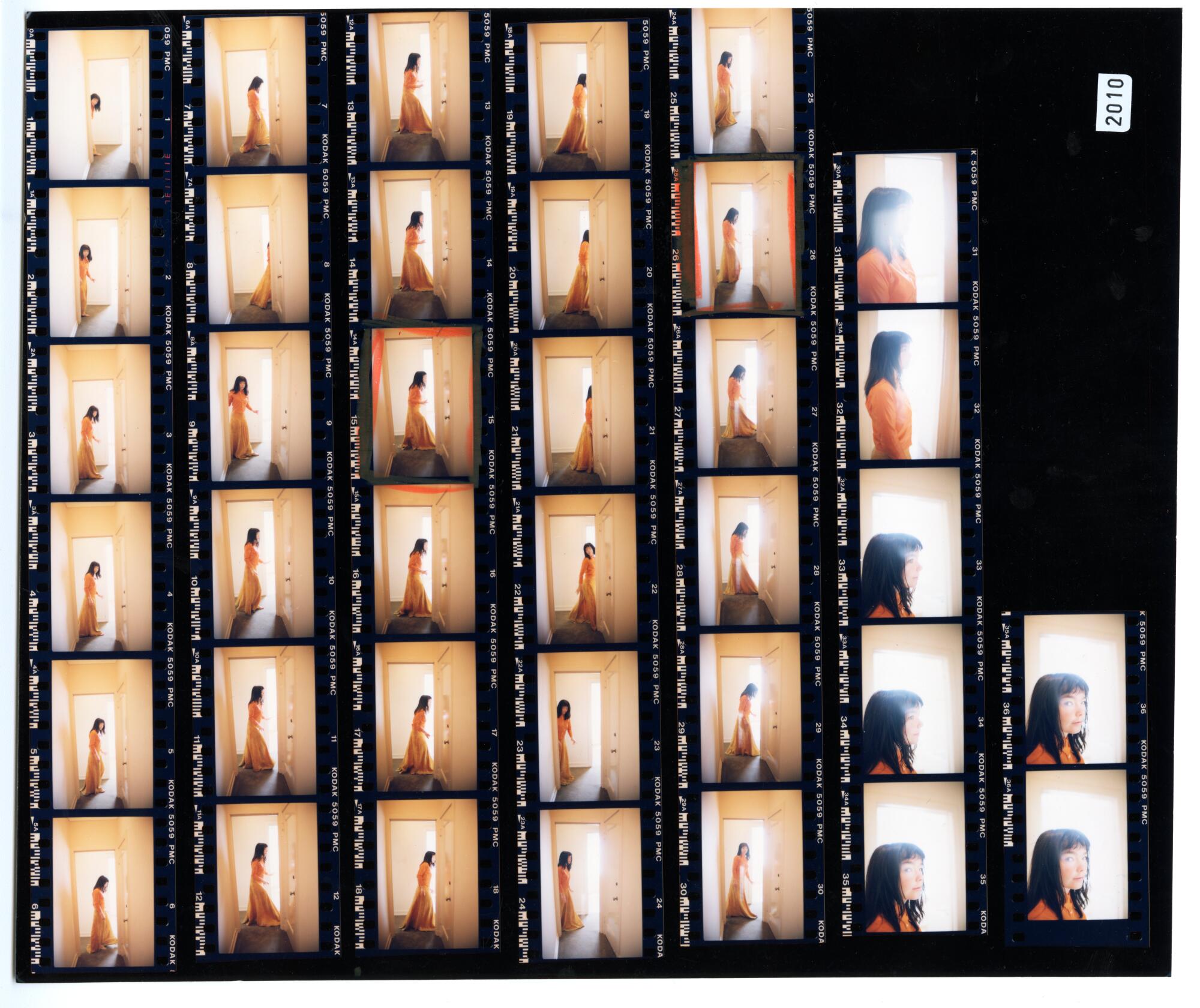

If we run our eyes up and down the contact sheets from the shoot, our minds can construct a moving picture of Björk as artist and muse. She steps through doorways, down hallways and toward the light. Engulfing her face, the brightness creates a white eclipse. While this series of photographs taken of Björk in orange relies on preternatural tropes, those made in the bathroom take it further, pushing into the realm of the supernatural, of time travel. In a pose reminiscent of the fight scenes from “The Matrix” franchise, Björk appears in suspended animation, her back arched, head frozen above the faucet, arms dangling at her sides. She stares up, at no one. The pose is vulnerable and just ethereal enough. It raises the question that we may, or may not be, living in the same dimension as Björk.

My favorite portrait created at the Chateau was shot underwater. Once again, Björk appears suspended, this time in rich blue. Her brown mane swirls and snakes, reaching for the surface. She is backlit by the L.A. sun, whose rays create an aura above her head. Her green dress summons the illusion that Björk is a scaly creature, one who breathes through gills and uses a tail to propel herself through lakes, rivers and oceans. She might also use that tail in self-defense. The photo recalls another classic ’90s image, Nirvana’s “Nevermind” album cover with the aquatic baby. While Nirvana’s baby spreads both arms wide, Björk uses her right arm to wave at the camera.

(Spike Jonze)

She seems happiest as a mermaid, and I can’t help but hope that her joy comes from her affinity for the sirens, those ancient Greek tritonesses who lured sailors with their magical voices, only to inspire these mesmerized seamen to sacrifice themselves against seaside cliffs. Björk is no Disney mermaid. Instead, I imagine that as a mercreature, she has more in common with Michi-Cihualli, the fish woman who dwells in Chapala, the Mexican freshwater lake where I spent some of my childhood. According to the Coca people, Michi-Cihualli is the daughter of Tlaloc, the rain god. When winds blow hard across the lake and storms brew over its waters, it is said that Michi-Cihualli is angry and must be pacified. Soothing her requires blood, and my imagination can easily conjure Björk accepting blood sacrifice, gnawing on the rib of an annoying sailor who dared to tell her that she looked exotic.

In 1996, a video of Björk attacking reporter Julie Kaufman at the Bangkok airport surfaced. The scene dispelled the popular image of the singer as a mindless, erotic elf and cemented her status as someone not to mess with, someone willing to draw a little blood. An artist in blissful control of her trademark strangeness, Björk’s way of being a weird woman in the music world meant a lot to aspiring weirdos like me. Instead of the typical hypersexualized vamp, Björk offered girls like me a different template, and the more bizarre she revealed herself to be, the more our loyalty to her deepened. Images of the singer were part of the collage that covered my bedroom walls when I was a teen, and I hope that the newly published pictures of Björk find their way into the right kid’s hands. There are so many girls who need a ferocious mermaid with a beautiful voice to sing them into adulthood.

Myriam Gurba is the author of “Mean,” a ghostly memoir about survivorship that was selected as a New York Times Editors’ Choice. Her latest book, “Creep: Accusations and Confessions,” was published by Avid Reader Press.