There he was, angel of mine.

It was the spring of 2023 and I was turning to walk back to my car. All four of the Baldwin Hills tennis courts were full, quickly ending my dreams of hitting some serves.

The lean against the fence is what first stopped me. That slight lunge with your arms both up, like you’re standing in the archway of your own kitchen, watching someone make grits. But it was also the fact that he was a Black man in his 40s (or maybe 50s? or maybe even 60s?) who felt familiar: He was dressed both as if he were someone leaving work and someone who valued keeping loose evening plans. (He was surely a regular, somewhere.) And yet, here he was looking on, intently, at the tennis being played on the other side of the partition. No athletic shoes and not a racket in sight.

His play-by-play commentary was impeccable — the digs were the kind you only give to someone you know, like a friend you’ve been verbally torturing for years. This banter volleyed across the court quickly between the man on the fence and his target, who returned serves and hit forehands and walked to retrieve tennis balls only feet away from the color commentary. Before long, the talk crescendoed: “Let me go get my shoes and my stick, I’ll be back, don’t you dare leave.”

Did he just call his racket his stick? Immediately, I knew I was home.

Every summer, from age 6 through age 17, I attended an all-Black tennis camp — the Southwest Atlanta sun blackening the berry that was my face and arms and legs. My childhood tennis coach was a man named William “Coach Wink” Fulton, who had made his way to Georgia by way of Winston-Salem, N.C., to attend Morehouse College. Tennis lessons from Wink were the thing of legend, he could carry on a full conversation with one person, comment on the strokes of a player on an adjacent court, and the second you — his primary focus — started to slack off because you were tired and you thought Wink seemed distracted, he’d stop feeding you balls and tell you about yourself. He was both a wizard and a man of the people, your coach and the whole community’s coach. The tennis center was, essentially, the barbershop meets the blacktop.

Over that decade, I went from the little kid who was fast to the quiet, slightly older kid who could really play, to a teen who possibly had all the tools to go far, to a camp counselor who liked the social element as much as winning matches.

My Black tennis community was, for me, akin to finding my church home. I grew up there. When I was 8, I lost my wallet; and when I was 16, I found it. When I began preparing to leave home at 18 for New Hampshire, I knew my future New England state could not fill the void of not having the camaraderie at the tennis center near. I didn’t expect to replace it — how could I? — though when I left for college I brought my rackets anyway. I gave a halfhearted attempt to make my school’s tennis team, but learned quickly that playing a Division 1 sport was like having a full-time job, which meant you couldn’t party and be a normal student. So, at age 18, I retired from my amateur tennis career. Through one lens, I was a man of unfulfilled potential; but through another, I was a guy who actually had a skill — a real foundation — that could let me play this sport for the rest of my life.

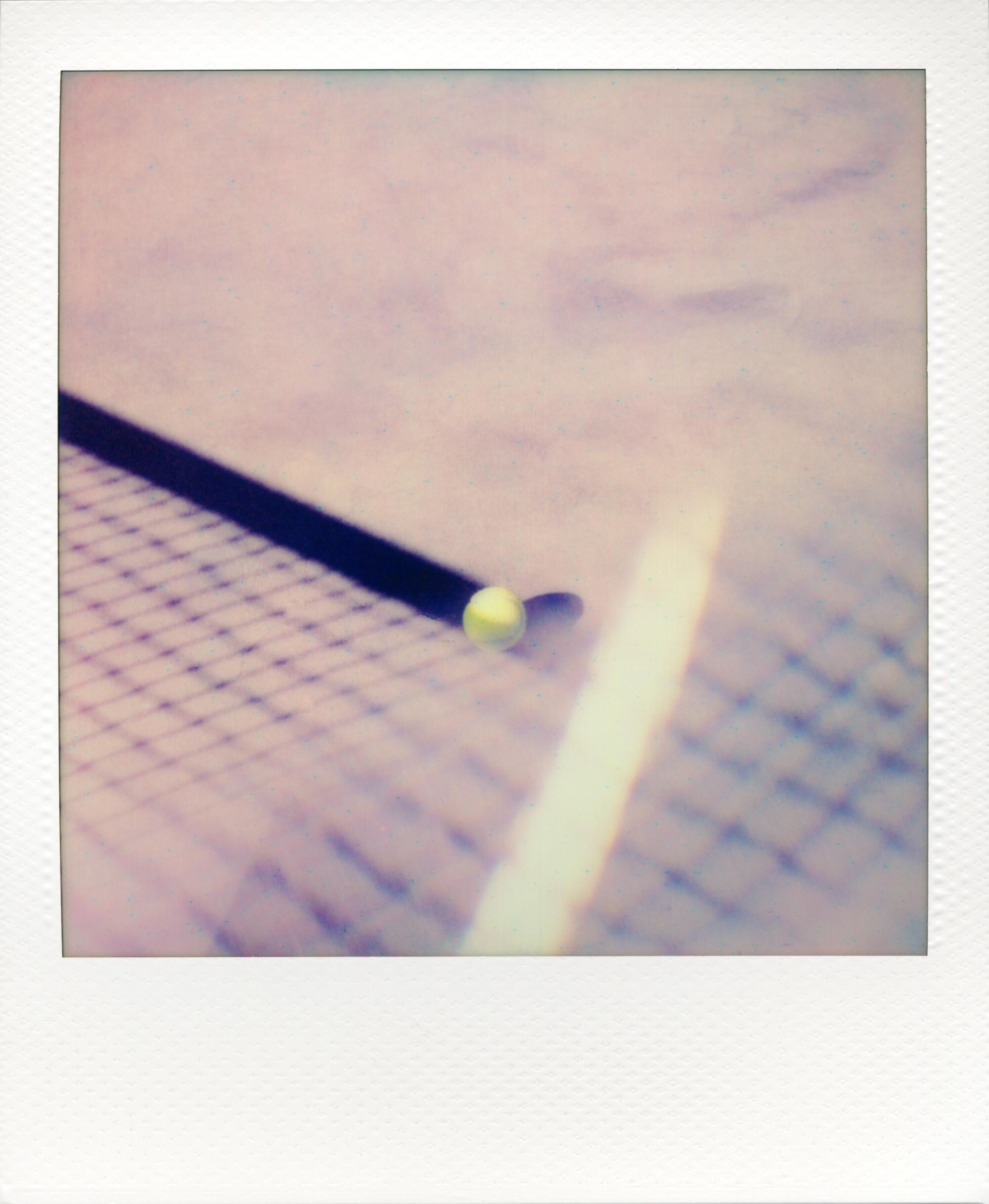

The court does something to me.

The stresses and obligations of the day and life temporarily halt.

When I moved to New York City in 2009, I again brought my tennis rackets. And over the 10 years that I moved neighborhoods — from Greenwich Village to Harlem to Hell’s Kitchen to Williamsburg to Bushwick — I could count the number of times I stepped on a tennis court with two hands. Yes, that math means more years than tennis outings. New York was the opposite of Atlanta — the former a city with fewer courts and 16 times the people. To play required waiting in long lines, waking up when the sun rose, and for certain months buying a permit. Many courts were gated off by pricey memberships. Yes, it was about the money — I graduated in the recession, there was no disposable income — but it was also the principle. I didn’t grow up paying to play tennis, I’d just wave at someone and walk onto a court. As for the adults, I used to see them pull out a $10 bill and get change back. Tennis was a public good, not a luxury.

In 2019, I moved to Los Angeles. Again, I brought my racquets, the same way one brings that old waffle iron from home that they never use but feels nice to keep close. Living less than two miles above that psychological railroad track that is the 10, most of my early adventures in the city involved looking north — it was no more than a 20-minute drive to Sunset Boulevard and all the things that existed between. But the void of existing in a Black neighborhood eventually kicked in, so I looked south.

That’s when I found them. Tennis courts everywhere, and all of them filled with Black people. I didn’t know any of these Blacks, but I was familiar with every character. A coach with a belly who moves quicker than you’d think. Friends taking long breaks to catch up before switching sides. The one kid who everyone has their eye on — and gives feedback to — because they might be the future. Loud talking, in a sport marketed as quiet. And laughter. So much laughter. After years of trying to figure out who I was going to be in Los Angeles, these courts reminded me who I actually was.

The court does something to me: Standing between those lines, my brain slows to a creep. I don’t think and then move — my body takes over and once a point is over, I walk to the nearest fence and think about what I just did. Or sometimes I don’t — I just keep moving. The stresses and obligations of the day and life temporarily halt. And once a good day on the court concludes, the various anxieties don’t rush back in, they saunter.

Life still goes on. Coach Wink died in 2022, a week before Thanksgiving. Losing him made the motions of tennis — and even getting on the court — difficult. But I wanted to honor him. And the best way I could think of was remembering the many lessons he taught me on the court : to keep my shoulders turned and not open them up on my groundstrokes (a thing he preached was the most important move in tennis). To keep my feet moving in the middle of a point (a must if you came up w/ Coach Wink). And, every now and then, to go for that big, sexy, flashy, near impossible shot to end a point (he never said this outright, but it was implied).

When I’d properly follow his teachings in Los Angeles — 80 percent substance, 20 percent style — I’d get the chance to answer the question of “where’d you grow up playing?” with “Southwest Atlanta.” I had returned to the court.

Stepping inside those fences in Los Angeles was spiritual, an opportunity to reclaim an energy that was lost. My competitive fire was no longer there, but playing wasn’t really about that anymore. The tennis court was now my spa, where I could relax, and my therapy session, where I could work things out. It was also a physical reminder of the community that I hold dear — the people who surrounded the sport I had to remain connected to, even if on the opposite coast from my home. The courts were a restorative space. There, I could restore that old feeling and embrace a journey toward being an old head — the guy who cares about the kids, the guy who can crank out a big shot, and the guy who always has something to say.

Rembert Browne is a writer from Atlanta. He lives in Los Angeles and is at work on his first book forthcoming from FSG/MCD.