“I have lived the most beautiful lives and died the most beautiful deaths” is a thought I had the other day while surfing. I had just paddled for a wave and then pulled out of it at the last second when I realized I would have to drop in at a particularly steep angle. I wasn’t in any real danger — the wave was sharp but small — and yet for the span of a heartbeat, I could picture myself pearling head-first down the face of the wave, my body thrown into the balletic arch of an angry scorpion, and my board pulled down behind me, unceremoniously yanked by my leash from its dolphin-like spirals up toward the sky, as if it were gasping for one last breath. It would all happen in a matter of seconds, but if you can imagine it in slow motion, it’s an unexpectedly exquisite dance; it is indeed a beautiful death. Instead of taking the chance, however, I shifted my weight back toward the tail of my surfboard and pulled up on the rails with my hands, removing it and myself from the momentum of the cresting wave. Every time I paddled for another wave that afternoon, the sentence replayed itself inside my head as if it were a well-worn mantra: beautiful lives … beautiful deaths … beautiful lives … beautiful deaths.

We often speak of the end of the world as if it were an event that will catch us off guard and erase our existence instantaneously, like a summer blockbuster coming to fruition. But I’ve lost count of the number of times I have lived and died.

In ‘I Just Wanna Surf,’ Gabriella Angotti-Jones dives deep into the way in which the cyclical nature of trauma and healing mirrors chasing a wave.

I’m thinking not only of every wave I’ve caught and fumbled but also of the many apartments I believed to be home, of every first and last kiss with someone I have loved. Each time I have understood my reality to be one thing, only for that thing to end or morph and render my existence brand new again, I have died a kind of death and then lived again. Like a lot of people, I remember the last time I left my office on a Tuesday evening in March 2020, unaware that I would never again see that place where I had spent most of my waking hours for years. And yet, we eventually showed up to other jobs, offices and coworkers.

What if the end of the world is a constant, rather than a finale?

To catch a wave in the first place, you have to sit close to the most powerful, and the most intimidating, section of it; you have to sit close to its heart. That peak itself is the wave’s last breath, so to speak, and when you catch it, you’re riding its final exhale to shore.

“Waves are not stationary objects in nature like roses or diamonds,” writes William Finnegan in his surfing memoir, “Barbarian Days.” “They’re quick, violent events at the end of a long chain of storm action and ocean reaction … The best days at the best breaks have a Platonic aspect — they begin to embody a model of what surfers want waves to be. But that’s the end of it, that beginning.”

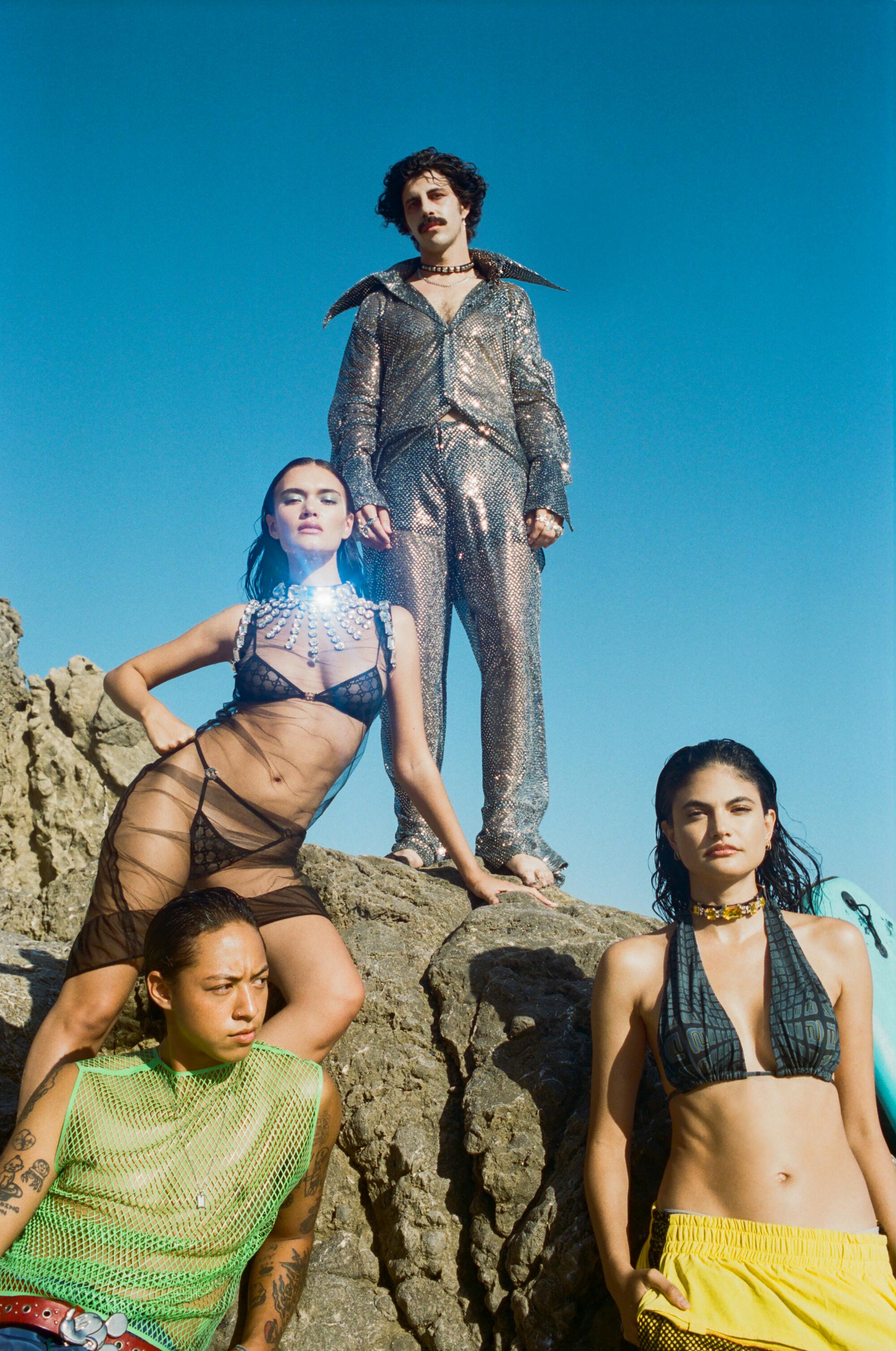

Ebony Beach Club shows why partying is a restorative practice. Whether you’re in need of healing from witnessing or experiencing pain — in the world, in yourself — celebration offers a clean slate.

In surfing, as on dry land, death begets life begets death begets life. Surfers put themselves through this life cycle over and over again in the water, learning to embody resiliency along the way. We pull out of a wave, aware of the risk and the discomfort, and then we drop into the next one knowing full well that we may not make it because, well, what if we do? To really live often demands that we place ourselves in the most vulnerable position, be it close to the heart of a wave or close to the heart of another for a first kiss.

The beauty of surfing is inextricable with the fear of it, even if, as I’ve gotten older, the fear has slowly taken over. I didn’t drop into that wave the other day because I was afraid. I didn’t used to be like this.

I broke a board once in overhead surf at El Porto when I was a junior in high school. The tail half of my board, still attached to my ankle by my leash, pulled me under the water again and again during that massive set of waves. My body tumbled helplessly like a rag in a washing machine for more than a couple of breaths. I could see the nose of my board bobbing in toward the shore, both a beacon of safety and a thing worth saving in itself, and somehow, I managed to swim toward it until I was sputtering on the sand. A younger boy from my varsity surf team was near me in the water that morning, the definition of a grom (short, sun-blond, already very good at surfing, a proclivity for the word dude). “Dude,” he said to me at lunch that day, “I thought you were going to drown out there.” I too, for the first time in my life, figured I was going to die, but when I was finally able to drag myself out of the water and onto the beach, I could only cry for the two halves of my beloved board, one tucked under each of my arms. Youth bestows a certain recklessness that comes along with believing that death is very far away, until one day you recognize how many deaths you’ve survived.

If, today in my late 30s, I am always afraid when I surf, why do I paddle back out?

Getting called a racial slur while surfing Manhattan Beach changed how Justin ‘Brick’ Howze and Gage Crismond view their role in the sport.

In his book, “The Drop: How the Most Addictive Sport Can Help Us Understand Addiction and Recovery,” Thad Ziolkowski writes about surfing as both an addiction and a palliative. To wit, he describes his decision to paddle out the day after 9/11, the very morning after the world ended.

“People find it strange or worse that I went surfing the day after 9/11, but for me it was like going to church — like psychic medicine, like sacrament,” Ziolkowski writes. “I was thinking about surfers who had called in sick to their jobs at Cantor Fitzgerald [to take advantage of a hurricane swell that morning] and lived — the mystery of who lived and who died.”

On his way to the beach that day, Ziolkowski got lost near JFK Airport and while making a sudden U-turn, he alarmed police officers in a nearby security kiosk. When they rushed out to question him, all he could say was, “I’m just trying to go surfing.”

Every time a surfer breaks a board, every time a surfer is forced to hold their breath longer than they thought possible, and yes, even every time a surfer pearls on a puny wave, they experience a kind of death. And yet, we’re all just trying to go surfing again. It’s as if the baptismal in the ocean were somehow both the original sin and its curative.

Skateboarding legends pay tribute to the iconic stairway of iconic stairways — a historic landmark where the evolution of the sport has come into view.

It’s an impulse that is even more perplexing when you consider that, in addition to being scary, surfing is absurd: It involves a ridiculous amount of effort for only an occasional, fleeting payoff. In Los Angeles, surfing is a lot of paddling through crowded lineups at point breaks or still-crowded closed-out beach breaks, and then not catching anything because of that crowd, or because the winds just shifted, or because you brought the wrong board for the conditions, or because the live video stream of the spot — which you triple-checked before you left your house — lied. And then when you do finally catch something, it’s for just a few seconds, maybe closer to half a minute if you’re having a very good day.

But during those seconds on a wave, sense and rationality cease to exist, because to hurl yourself down a small cliff of fast-moving water, your body must betray your mind: You must override your brain, which says, loudly and sternly, “No,” by moving your body toward “Go.” In other words, you are young and willful and immortal once again.

Each time I have caught a wave, I have been suspended in these liberating seconds, where there is only my body as a kind of hitchhiker upon a pulse of energy — energy that was generated from a windy storm thousands of miles away, pushing its way through quantities of water too vast to imagine, to end up here, under my feet, where it will finally exhaust itself after its long journey, as a sputter of whitewash upon the shore. It is impossible, this wave, and it is a little miraculous. When you ride it, you too are impossible and miraculous, existing in the threshold and no longer bound to the realities of the world. Surfing is scary because death is scary, but every time a surfer catches a wave, they get to live a different version of life, a beautiful one, if only for a moment or two. It’s why, when I finally manage to catch a wave only to end up face-down with water up my nose, tangled in my leash and gasping for breath, I turn around and paddle back out again.

If you ask a surfer about the end of the world, they’ll tell you it’s when there are no waves and they’re stuck on dry land, waiting for a swell. But if you watch a surfer in the water, you’ll see that they’ve got it wrong. Surfing involves a lot of waiting — that part is true — whether it’s in the water or out of it. And most of the time they’re in the lineup, surfers are just sitting, facing the horizon, because that is where the waves come from. Which means that most of the time, surfers are staring down at the edge of the world, the end of the world, in anticipation of what comes next.

When I thought, “I have lived the most beautiful lives and died the most beautiful deaths” the other day, I wasn’t thinking about the waves I have caught and all the waves I have only just survived. I was thinking about heartbreaks and COVID and about people and places I no longer know and about all the other times the world has ended in my thirtysomething years. And I was thinking about how, in between those endings, life was the most beautiful. Then, I paddled again.

Producer: Rafaela Remy Sanchez

Models: Jensen Fairchild, Momo Kun, Josh Landau, Xenia Ortiz

Makeup: Yasmin Istanbouli

Hair: Adrian Arredondo

Styling Assistant: Lizbeth Garcia

Claire Salinda is a writer and tarot reader from Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in the Missouri Review, Assay, G*Mob, Thrillist and other publications. She holds an MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars.