This story is part of “Corpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser,” a special collaboration between rafa esparza, Image magazine and Commonwealth and Council. See how the whole project came to be here.

I grew up in the San Fernando Valley. I’m first generation; both of my parents are from Atlixco, Mexico. I definitely think that my parents’ background has influenced the kind of work that I do. I didn’t necessarily have a very clear idea that I wanted to do art. I’ve always been a maker. My dad has always been a maker; he taught me and my brother from a very young age how to build around the house. We would help him literally break down this wall, put another wall up, tile the floor. It was just so common for me to know these things, like stuccoing the door, the house outside.

When I was younger, I took it a little bit for granted the kind of labor — this knowledge that I was getting from my family. As I got older, I started realizing that I had a very specific way of working with material, with matter. I started working with clay. I love the material. It’s so malleable, so intuitive. It’s so much about touch. That’s when I moved over to metal and around the time when I met rafa esparza. I was working with the artist Beatriz Cortez. I started knowing that art is beyond something physical — it’s the interactions, it’s the knowledge that we’re exchanging. Meeting people like Beatriz, and then rafa — because they were collaborating — was super important for me.

Before I had met rafa, I had seen his work at the Hammer. I loved it. He had laid adobe on the floor, and there was a little couch with a cactus growing out of it. And I just thought it was so beautiful, because it wasn’t like the other things that I was seeing within that museum. It must have been a month or weeks later that I met rafa. It’s kind of funny how it all just kind of came to be, and then also to meet these people who come from similar and different backgrounds, who also have these relationships with labor and how that kind of labor informs what they’re making. Art had been abstracted so intensely for so long that it was refreshing to finally meet people who could be talking about really real things. And, I mean, poetic things too, and getting deep with them and thinking about them extensively.

I work in a lot of different mediums — like sculpture, and within sculpture, clay and metal, and performance, and there have been moments when they intertwine. A lot of my inner issues that I’m trying to resolve come out in the work, whether it’s direct or not. I try to understand how the personal is also in relation to something that’s a lot bigger.

Right now, I’m focusing on the relationship between humans and dogs — on a personal level, just looking at my relationship with these animals and seeing how the love relationship and the care relationship come more intuitively than it would with another human being. I’m learning about this companion species and tapping into this relationship between specific animals and humans that is very, very old. I think humans are super removed from their inner being and being in tune with nature. And I think other species — it doesn’t have to be a dog, for some people, maybe it’s plants — have mythically, historically been there to guide us.

It’s been exciting to work with rafa on his work for Art Basel because even in my performances, a lot of what I do is become the dog. I’ll wear armor to be it and kind of step into it. I think his work does tap into looking back at different kinds of creatures, looking back at plants, but the cyborg is these extensions of oneself. It’s been great to be working with rafa and be thinking about what these extensions fully mean.

I think rafa brought me on to this project primarily because he does know me as a fabricator; we’ve worked closely together on different projects. Right now, we’re building the lowrider bike. We’ve had to create the piece out of fiberglass, cut it up to get it casted and molded, get it back in parts, welding the aluminum together. We both work this way where it’s very much just, ‘OK, what do we have? How do we make it work?’ Which is great, because not everyone can work like that. And not everyone wants to work like that. It’s good that we can; we’ve been figuring it out as we go.

When you’re thinking of working on cars, building something together, it’s rarely isolated. It’s rarely a one-person thing, there’s usually a whole network of people; a whole network of knowledge is being exchanged. We could exchange this lowrider bike sculpture — it could be a car that we’re talking about. Also, we started out in his studio and then moved into his garage. His neighbors come by, and they talk to us; they ask us what’s going on, people are making jokes of the pieces we have. And it’s really funny because we’re like those guys who are working in the garage on their car, except it’s me and rafa instead — we’re working on something very similar, but then it gets very queer, and I do love that.

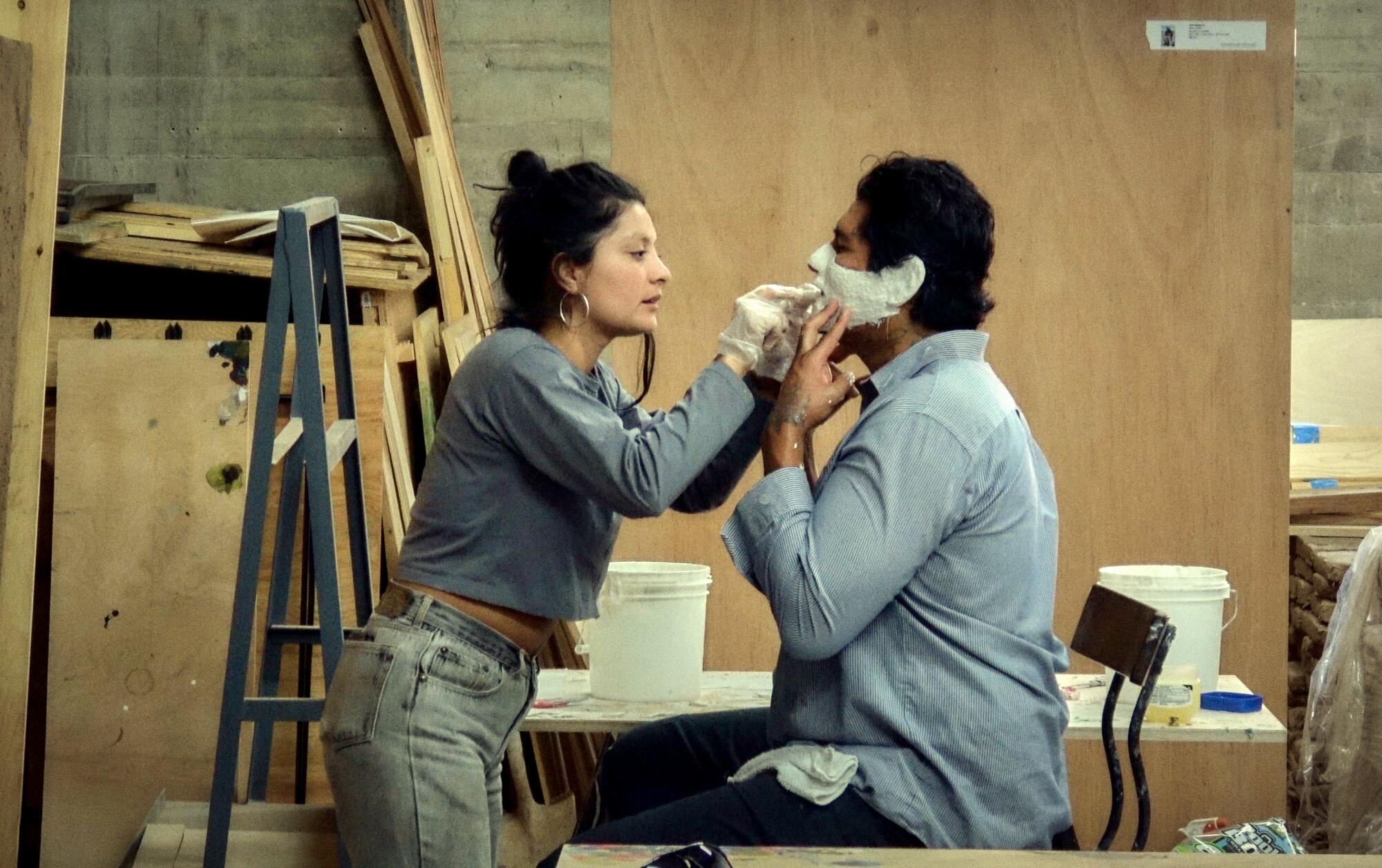

We’ve also been casting rafa’s body. It’s so personal — I’m casting rafa’s f—ing foot like 10 times. It’s super interesting, because we’re taking this marker, we’re capturing his foot, but we’re also transforming the body. We’re making this lowrider a kind of ship — this thing that’s going to be carrying a seed into the future.

If we made a myth for this sculpture — this creature that rafa is making — what has it inherited from rafa? What are the imprints that rafa left on it? What has it learned from him? And what does it know beyond him?

We’ve been looking at different images of Aztec and Mayan references, these pre-Columbian, ceramic works. The thing we’re making doesn’t look that different from those things. There’s kind of a lingering memory that’s here and that’s also beyond us, beyond time, that’s being captured in this piece.