When Reparations Club opened its doors in 2019, it was clear: This was more than a bookstore or retail shop. There was something sacred about the space itself — what having a Black woman-owned slice of real estate in L.A. meant. After relocating during the pandemic, that energy remains. Books by Black authors line the shelves, serving as a gateway to an open-format space where in-person karaoke sessions, intimate artist conversations and queer game nights happen on the regular. The setting itself feels like the cool living room we all want: stylish, but hugs you in comfortability and warmth.

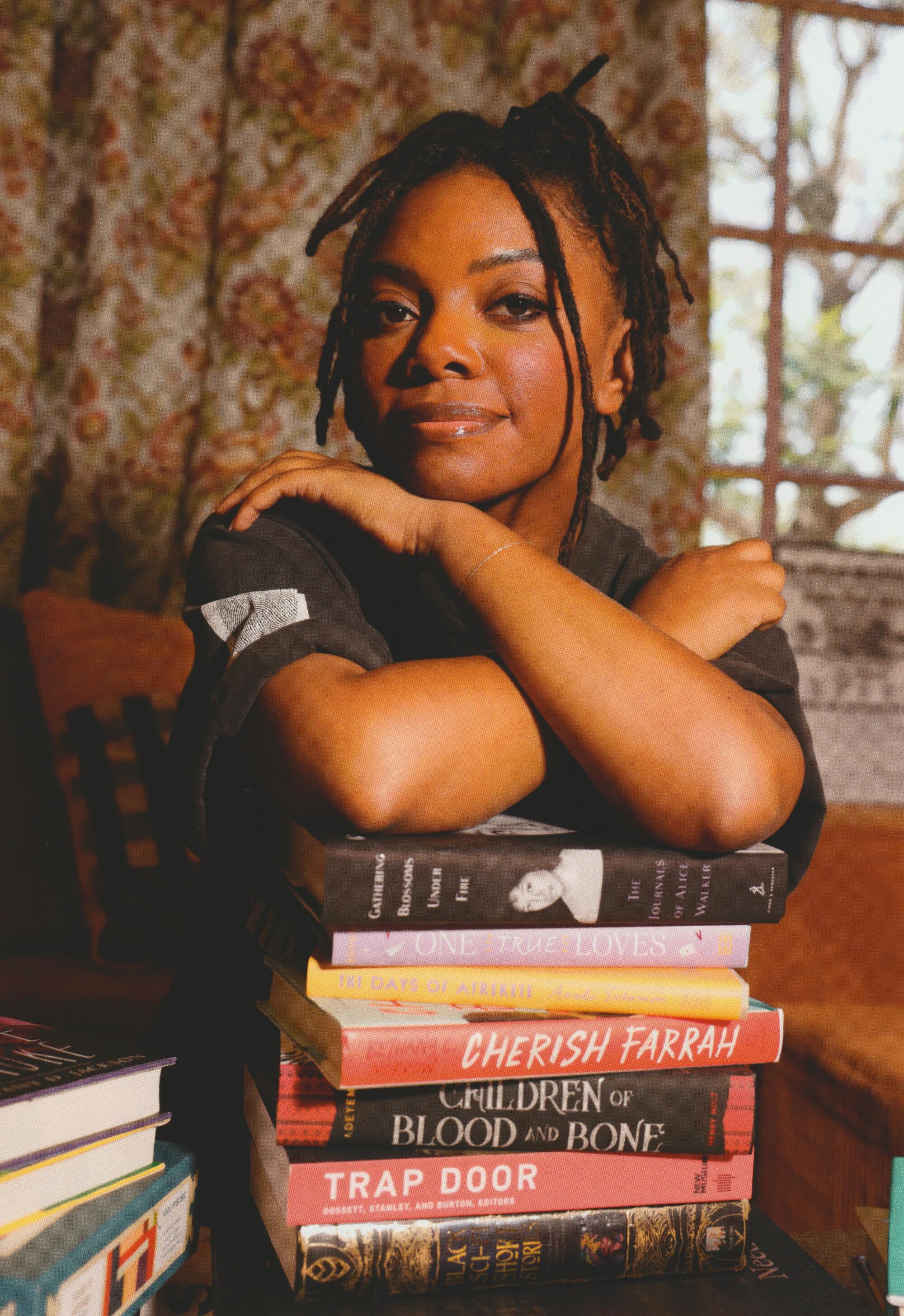

For founder and owner Jazzi McGilbert, Reparations Club is a physical offering for Black people in L.A.: It’s somewhere, ultimately, made for them to be themselves. Ahead of Juneteenth, McGilbert spoke to Image about the importance of physical space and the ways it can liberate us.

I try not to define it as much as possible. But when I have to, I say that it’s a concept bookshop and creative space — because that leaves the door open for absolutely anything to happen here, which it does.

I wanted somewhere that prioritized Black people and, by extension, other people of color, but wasn’t like everything else that felt pandering to the Black community, that didn’t feel like it was actually for us. I wanted to make a space where we can hang out, where we feel centered, at home — like kick your shoes off. Where we have the same points of reference.

The only space where I had felt that at all was the Underground Museum, where I had my mom’s funeral. That was a space my mom and I had gone to before, and I remember being like, “Oh my God. Look: Black art being given the reverence that it deserves.” I wanted to replicate that feeling, for there to be more than one space that could do that — and make it a retail space, not necessarily an art space.

If you were to tell Jazzi five years ago what I’m doing now, she would be surprised. Most surprising thing is that I’m the boss. I didn’t think that was possible. It would have shocked me to find out that I call the shots somewhere and that people resonate with it. I naturally gravitated toward all the things where I felt there might be a sense of creative freedom — and really, those creative freedoms didn’t necessarily apply to me. I ended up in fashion and styling, but then you get into the industry and you realize it’s very commercial. As a Black girl in the fashion industry, I had this intersection of not being the physical body type, and then all the class issues as well. (I don’t come from a family with a ton of money.) It always felt like this huge uphill battle that I was losing. Eventually, I just decided to go with the flow, which was not toward the fashion industry. It was toward something very, very different. Reparations Club felt like this big hypothesis that I had. A huge experiment that’s working so far.

And then the books part feels ironic. I was a very bookish kid. Introvert. I loved reading, but I had fallen out of love with it. When I opened the bookstore, I didn’t even know the last time I had really picked up a book. I’m still discovering this stuff. But I know it’s amazing and it’s getting back to this childlike energy that I had for reading.

Liberation here shows up in a lot of ways that I’m really proud of. It’s every day — whether that’s someone walking in and pausing, hands out, like, “Wait, whoa. This is in this neighborhood? Why didn’t I notice?” The reactions of people really feeling seen and understanding immediately that this is a thing for them. Or our staff: Our general manager was working at another bookstore where she was not centered, didn’t feel represented and was fighting all the time to see herself reflected on that shelf. There are so many little things that you wouldn’t get in another work environment. It’s liberating for me, and I know it is for them. Like, being able to borrow your boss’ car if you need to get somewhere — I’ve been in a work environment where my boss never would have loaned me their car — or being able to ask for a favor. It’s just not a toxic work environment. A little unorganized, maybe, but it’s not toxic. Just being able to find other people who didn’t feel heard and give them a platform has been awesome. And then also all the authors we’ve connected with.

Every day here is pretty special.

I think that’s why the physical space is so important — because we’re all out here kind of aimless and we’re looking for community and connection. The internet is what opened up my world, but you can’t hug someone through a computer. Feeling safe and being able to just hold conversations … I think it’s about what the space can hold.

These spaces are disappearing, especially in this city. Our rent is insane, and it’s only going up. We’ll be here as long as we can be, but I wish there were more spaces like this. For me, it was Barnes & Noble at the Westside Pavilion. It was the ArcLight. The first place I felt myself reflected back at me was the Slauson Swap Meet. That’s such a landmark, I hope it’s there forever. That was the space that I was like, “Oh, this was made for me.” These are the price points that are accessible to me. Everything that I need is here — all of my hair stuff, if I need a cute outfit — it’s all right here in one place. That was really important to me. A lot of my family is buried at the Inglewood Cemetery. I learned how to drive there.

I want Black people in L.A., and even outside of L.A., as we get pushed out farther and farther, to take up space very loudly. There’s something about being able to be your authentic self. There’s a lot working against us, but wherever you can do that without the pretenses, without filters, I think that’s incredibly liberating.