When we talk about suit jackets or blazers, we don’t often throw around the word “liberation.” The traditional men’s suit is designed to constrict and to conform. It might not fit the modern definition of “workwear” as a genre of men’s fashion — your double-knee pants or your chore coat — but nevertheless, the suit jacket is very much what one wears to work.

Yes, believe it or not, there was a time when people wore suits to work. Most of my first few job interviews in my career required me to troll through H&M praying I could find trousers that didn’t make me look like a burlap sack overfilled with Christmas presents. Traditional suiting can feel like an assault on the body, unless you are one of the lucky few who can afford bespoke tailoring. You are at the mercy of the rack and the need to conform to what the world considers the proper fit for a suit at that time.

Who says you don’t need outerwear in your closet in L.A.? How to find the perfect jacket in a city of microclimates and many moods.

When I first moved to L.A. from San Francisco, in 2007, suits were razor-thin and inhospitable on purpose. The sharp, clean J. Crew Ludlow suit was the pinnacle of affordable masculine style. Scott Sternberg’s Band of Outsiders was making suiting that was snug, short and made one look like a prep school kid. “Rushmore”-core, if you will. I was too tall, too wide and too poor for those. But I soon discovered that I really had no need for a suit in L.A. For many Angelenos, a suit is a luxury item — something to wear at weddings, funerals, religious gatherings and the odd court appearance.

A fully trad, normie suit pegs you as a lawyer, a finance bro or one of the morticians from the HBO show “Six Feet Under.” It’s not that work isn’t done here. It’s that work does not require peak lapels. Even agents aren’t really wearing suits anymore, since COVID-19 has moved so much of the work of Hollywood to Zoom. This is not to say that Los Angeles is a tailoring desert. It’s that people who live here think of suits with a different ideal in mind: unstructured, loose, progressive. Angelenos value things like outdoor lunches, convertibles and “when I say 8-ish, I mean 9” scheduling, so our suits must capture the spirit of Western freedom that matches our perspective. Which is why the Armani suit is the unofficial suit of Los Angeles.

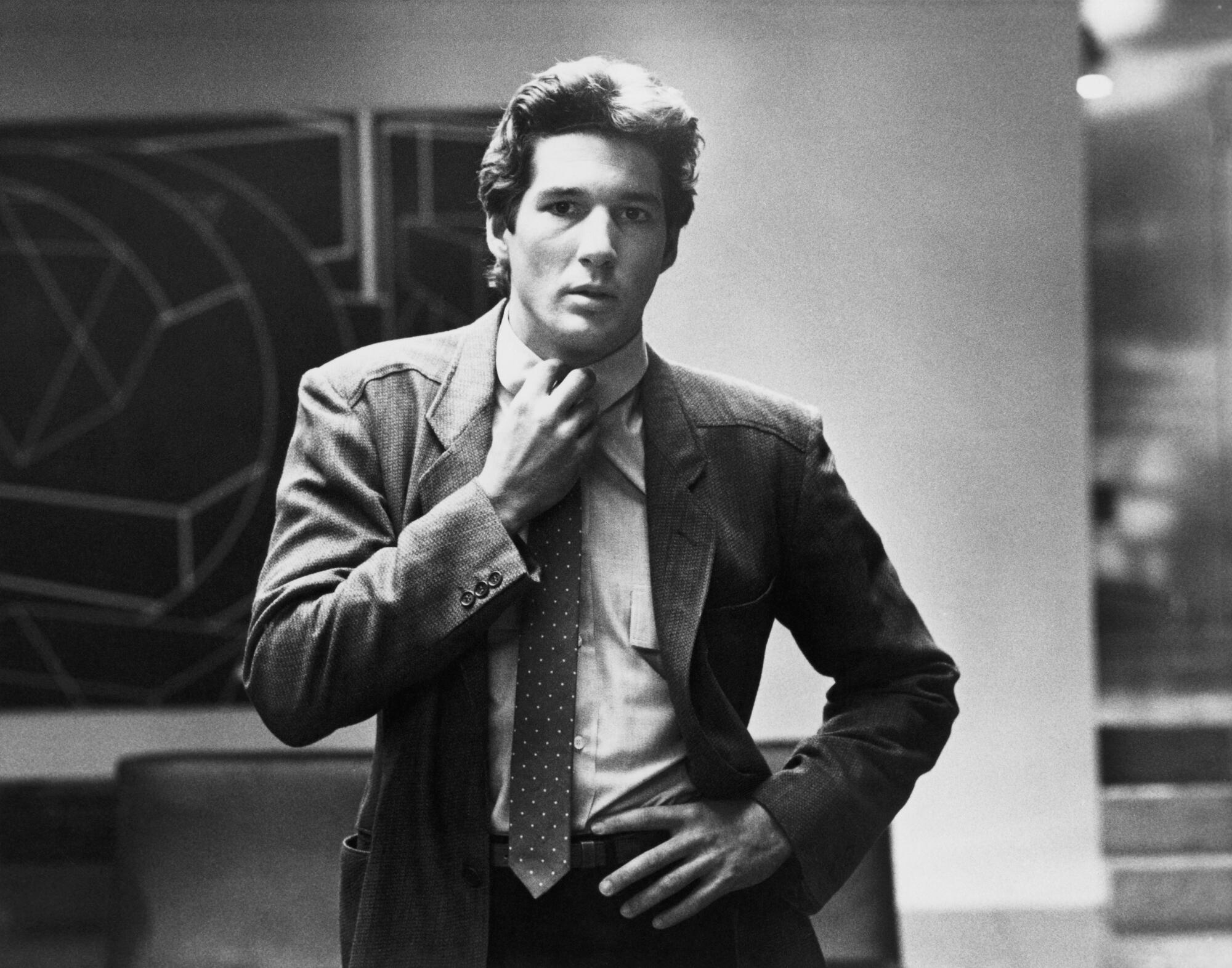

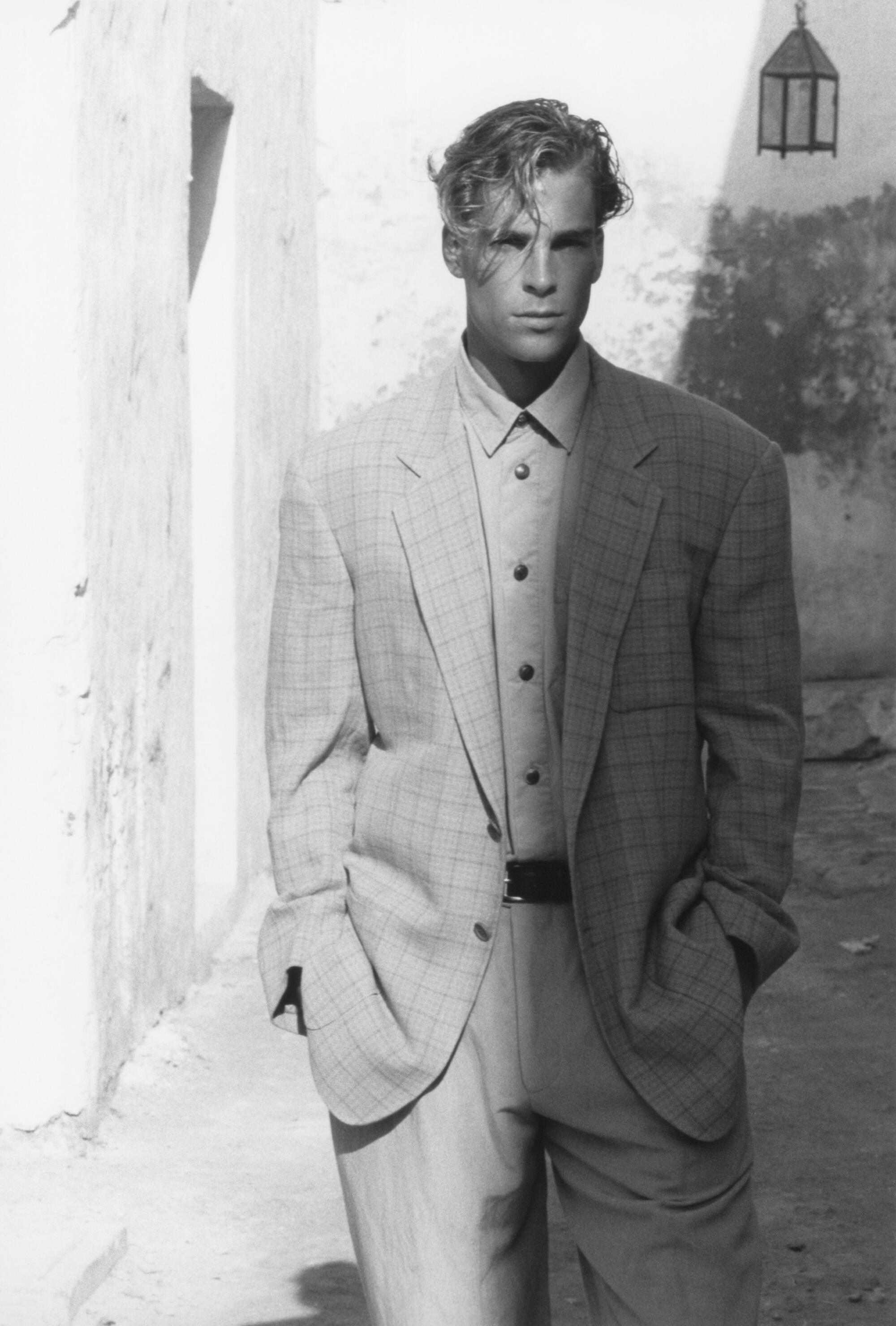

Maybe it’s the similarities between the Mediterranean climates of Italy and Los Angeles that helped foster this unique connection. It’s not that Armani, a quintessentially Italian brand, isn’t popular in places like New York or Chicago; it simply feels right here. Armani took over the cultural consciousness in 1980, thanks to the influence of the popular Richard Gere film “American Gigolo.” The muted colors, slouchy draping and effortless cool of the clothes captured the imagination of a culture that was ready to move on from the wilder aspects of ’70s disco and punk aesthetics. It was the gateway drug of choice for the yuppie generation. The suiting was more naturalistic and hung on the body in a way that wasn’t as constricting as your common American Brooks Brothers cut. The Armani jacket was an adherent of the brand’s philosophy: to wear one is akin to applying a second skin.

The glorious tailoring of Armani appealed to menswear fanatics who studied opinions on vents, darts and waist suppression. But what made Armani iconic to the average consumer was its connection to Hollywood. Armani — the brand and Giorgio Armani, the man — spent years cultivating a relationship with celebrity. (The reopening of the Beverly Hills Armani store in March spoke to this; it was as good an excuse as any to fete Nicole Kidman ahead of the Academy Awards. The store is clean, modern and classy in the way that Armani has always been, but it’s also designed to be a magnet for the rich and famous.)

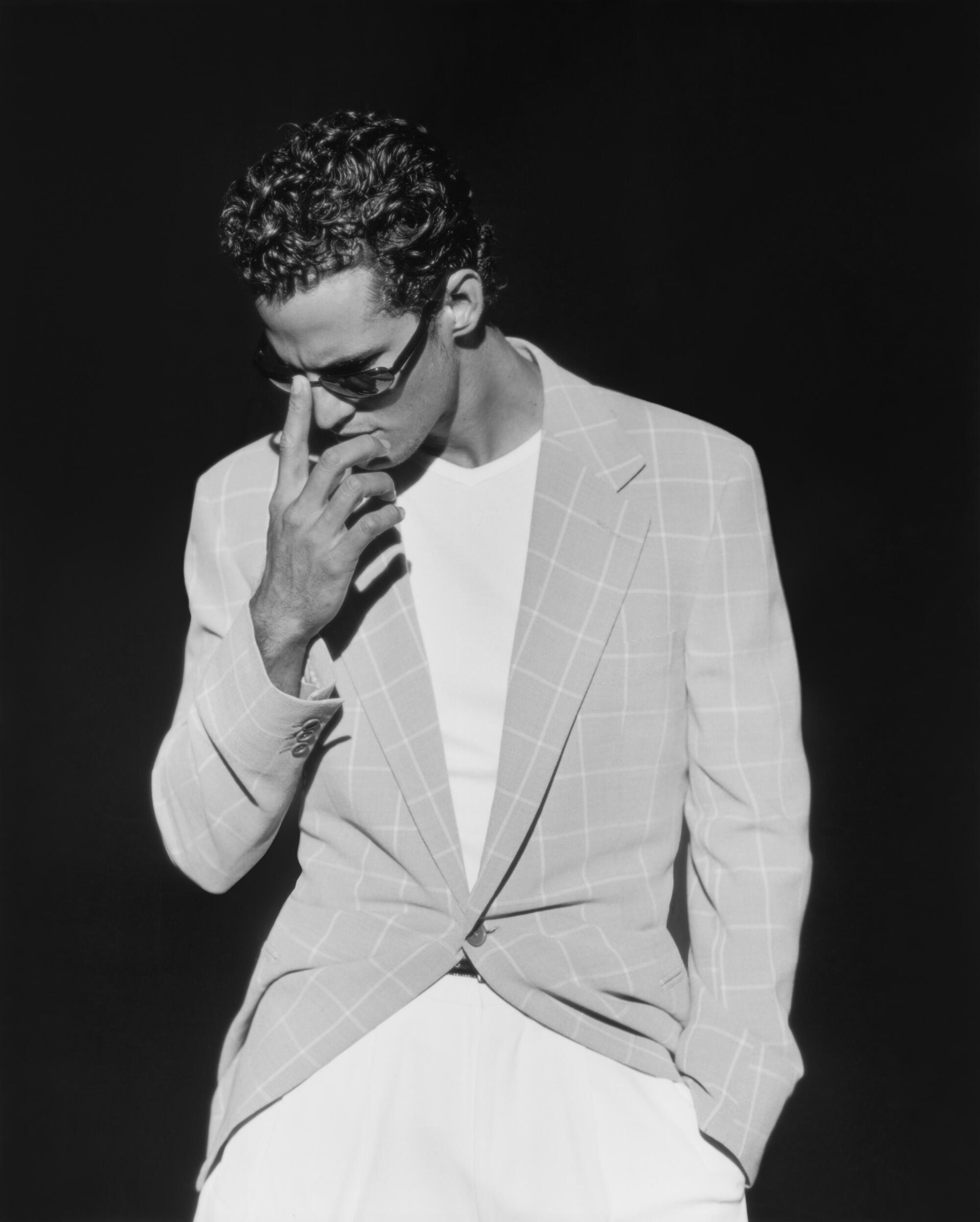

Through the ’80s and ’90s, the most common silhouette seen at film premieres in L.A. was a suit jacket or blazer, often Armani, casually paired with jeans and a button-down. That versatility lent itself to the men’s red-carpet style of the time: more concerned with comfort than the bold choices we see in celebrity styling today. Unstructured, drapey suit jackets could convey sophistication without the restrictions of the traditional suit. We see Armani’s influence all around L.A., but never more acutely than in the tailoring of Jerry Lorenzo’s Fear of God. Southern California cool is an intrinsic part of the brand, not just in the sumptuously constructed sweats, but in the loose, comfortable suits in tasteful neutrals similar to those Armani blessed the world with back in the 20th century.

To figure out what it means to be beautiful, you must banish the fear from your brain

To Armani’s credit, the brand retained its perspective through the decades. Tastes swung toward the snug suits of the 2000s, but instead of scrapping its heritage and trying to play catch-up, Armani kept refining its perfect formula through the start of the 21st century. Today, vintage Armani has become one of the most popular categories in the rapidly expanding resale market that relies on customers trying to flip their gently used grails. Armani has benefited from nostalgia, but also the pandemic-era interest in generous silhouettes that don’t require the wearer to hold their breath to fit into them.

The latest in the evolution of Armani’s iconic jacket is the Upton, a double-breasted, unlined piece with a standout topstitching design that looks a bit like herringbone from a distance. The peak lapels are high up on the jacket, and the shoulders adhere to the natural shape of your body. In many ways, it’s a classic Armani piece — sophistication in its most understated form.

Louis Vuitton bottles up the idea of L.A. and what it inspires.

It’d be a stretch to say that Los Angeles is understated in just about any way. This is a big city, a diverse city and a city that is far more unpretentious than its reputation. The working class that has no need for tailoring doesn’t see freedom when they see a suit. A suit can, understandably, represent oppression, the indifference of the privileged, or an unattainable standard. So how does a $2,400 suit jacket represent all of L.A.? Sadly, it can’t. Nothing can represent the entirety of a place this complex. Fashion designers can tell you they “captured the spirit of L.A.,” but that’s a fantasy. Maybe you can bottle up a slice of it, but never the whole thing. It simply won’t fit in the bottle.

Armani vibes with L.A. because it doesn’t try to “be L.A.” It doesn’t pander. It plays hard to get, just like the city itself. People come here and get lost in the sprawl, the never-ending concrete arteries, the loneliness. Maybe they leave for good. Or maybe they stick with it and find their own version of paradise. It’s expensive. It’s not for everyone. It’s for those that get it. Just like Armani.

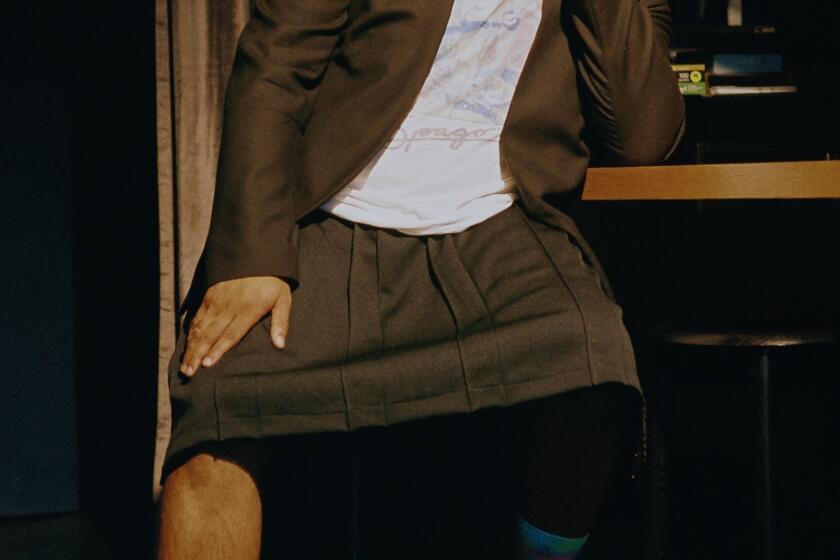

But the brand is not resting on its laurels. What’s unique about the Upton is it eschews the length that’s become so popular with vintage pieces from the ’80s and ’90s. As a tall man with a, shall we say, “substantial” rear end, I appreciate the longer cuts of the vintage jackets. The Upton also moves away from the flapless patch pockets that have been a staple of Armani tailoring for decades. The flapless pockets became a popular place for men and women to slide their hands into to add a roguish flair to their outfits. I instinctively want to put my hands in these pockets the way I do all of my vintage pieces, but the pockets simply aren’t designed for such things.

One might begrudge Armani for doing things that aren’t in line with the youth market discovering their archives for the first time on TikTok, but the brand is confident enough to play around and try new things. The old stuff will always be there, on sites like Grailed or eBay, or in your parents’ closets. Despite some of the changes to the formula, the Upton is a translation of Armani’s core aesthetic principle: that clothes should be made not for dress codes, boardrooms or corporate retreats, but for the way human beings really live. It’s the unofficial suit jacket of Los Angeles because this is a city that puts living above all else.