This story is part of L.A. — We. See. You!, the second issue of Image, which explores various ways of seeing the city for what it is. See the full package here.

“Junk art, assemblage art … it’s as close to human existence because it’s all castoffs we are utilizing here,” Noah Purifoy once said in an interview with fellow artist Joan Robey. “Because it’s your shit that we’re remodeling … and you got rid of it. And I come along and pick it up. And you say, ‘Oh, that’s junk.’ Well fine, that’s junk, yes.”

Fine, that’s junk. I love this posture — the way Purifoy is ascribing a Black dimension to the practice of assemblage art. You don’t know shit about junk, he seems to be saying. To whom he is directing his scorn is unclear, but he’s practically snarling at them, whomever they are. His quip imbues junk with a secret life, sitting just out of the view of those who have discarded items that lack any obvious use value. What his quip points to is a complete lack of interest in the society that has rendered certain people and things disposable. I have this feeling that what Purifoy was searching for with his assemblages was the social life of junk — not only inanimate objects but also all of us castoff people who were formerly things and must continue to function as things for the world to continue on as it does.

Black Los Angeles’ politically engaged culture of assemblage art percolated up out of South Central’s living rooms in the 1960s and ’70s, building on the legacies of Modernist art, folk practices and various non-Western traditions. In the context of Los Angeles, it was an explicit attempt to transform lack into bounty. Along with practitioners like John Outterbridge and Betye Saar, Purifoy was a key figure in the cultivation of assemblage, or “junk art,” as he called it.

A peripatetic figure, Purifoy was born in rural Alabama in 1917 into a poor family for whom, like many Black people, the ingenuity of invention was a fact of everyday life. He arrived in Los Angeles with a master’s degree in social work in hand and worked at Los Angeles County Hospital before eventually toggling to art. In 1953, he became the first Black student to enroll full-time at the Chouinard Art Institute.

It is impossible to consider the history of Black arts culture in Los Angeles without acknowledging its debt to Purifoy as both artist and thinker. As he cobbled together a living as a furniture maker and interior designer, he theorized an approach to art that emphasized aesthetics as a social tool. From his apartment, he proselytized to guests like Outterbridge, David Hammons and Judson Powell.

More from issue 2 of Image

Darian Symoné Harvin talks to Lauren London about Nipsey Hussle, acting, and how seeking truth is an act of love

We wanted to know about the real L.A. So we asked our favorite Angelenos to show us

Ismail Muhummad meditates on how Noah Purifoy imagined a future where people aren’t discarded

E. Tammy Kim talks to the activists who have the antidote for the erasure of East L.A.

Julissa James profiles the L.A. designer who remade the cobija into luxury fashion

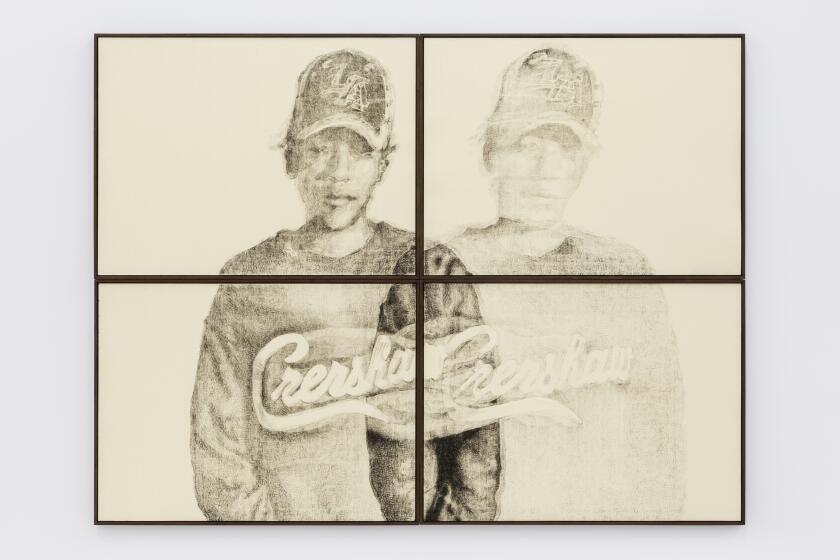

Ian F. Blair talks to Kenturah Davis about language and the tradition of Black art from the foothills to South L.A.

Along with Powell and Sue Welsh, Purifoy co-founded the Watts Towers Arts Center in 1961, turning Simon Rodia’s monumental Watts Towers into a site for arts education and community engagement. As Kellie Jones tells us in her history of Black art in Los Angeles, “South of Pico,” “Its mission would be to address ‘problem’ youth by using arts as a tool of cultural uplift, which at once demonstrated art’s value and the good works that the Watts Towers could perform.”

Convinced that Black creative culture could be harnessed for social uplift, Purifoy used the center as a forward base from which to spread his ideas via theater, painting classes and other forms of community engagement. He hoped that art making would be an avenue for the development of self, healing and even connection among disparate elements of society.

It took the historic frisson of the 1965 Watts Rebellion, though, to crystallize his ideas into an aesthetic. In the uprising’s aftermath, Purifoy and Outterbridge began to collect the signs of its wreckage, hoping to turn them into sculpture that could express the interior life of the Watts ghetto. The results of their exploration became the seminal assemblage art show “66 Signs of Neon.” Hinting at the lively artistic and political imagination that undergirded the uprising, “Neon” asked viewers to think of “junk” as a sign of art’s transformative potential and the power of the creative act to reshape the context in which it took place. An attempt to highlight the artistic energies that Black people held in abeyance, the show asked what we might discover when we refuse to segregate the reality of oppression from the pleasures of life lived amid that oppression. It makes us wonder: In the districts that have been relegated to those our society deems disposable, what can we discover about the lives of the disposable?

But the resulting works were only glancingly interested in representing the eruption that sparked them to life. Purifoy’s own “Sir Watts” was a suit of armor whose transparent front revealed an interior filled with utensils and other metal objects; safety pins spilled from a gash in the armor like a wounded warrior’s innards. Such abstraction demands that we think of the sculpture as more than an expression of a communal trauma. It’s possible to read the sculpture as gesturing toward the wounds for which the rebellion demanded redress; but reading it this way would dismiss the peculiarly inward-looking quality suggested by the knight’s lowered head. I’d rather read the sculpture as the sign of a mind investigating itself, a member of a discarded class discovering its own beauty and feeling a little sad that others cannot discover it as well.

When I first encountered Purifoy’s art as a high school student in an art history class, I felt called by its disjointed and insistent abstraction. The mischievous, jagged and melancholic introspection of “Sir Knight” moved me to think about the place I was from — South Central, Baldwin Hills to be specific — in a way that representational art had never instigated. It taught me to be interested in what the streets I called home had to teach me about the life I was living and my own potential for artistic creation. I could no longer ride down streets like Crenshaw or Florence — boulevards whose storefronts still sported the “Black Owned” signs that went up before the 1992 uprising — without imagining them as versions of Purifoy’s Watts. I began to wonder whether I, like him, could think of these streets and the detritus that lined them as the raw materials of an art that might express the beauty of my life amid the wreckage. He taught me to pay attention to detritus. If I did, I could see how wreckage was also a sign of life: What had been classified as “junk” was just art waiting to be shaped by the force of the imaginative act, waiting to be connected with other elements that would illuminate junk’s latent worth.

I have been thinking about this lesson a lot since 2018, when the city fenced in Leimert Plaza Park, separating it from its namesake neighborhood. Eventually, a tall wrought iron “decorative fence,” painted a garish blue with golden highlights, enclosed the park. As far as I can tell, the fence’s gates have never opened to welcome anyone past the new perimeter. Made to reflect the Art Deco influence of the nearby Vision Theater and the fountain that sits at the park’s center, this border was and is grotesque to me, a carnival-esque taunt to the neighborhood’s residents.

The fence’s purpose was to prepare the park for its future. North and south of the neighborhood, city workers were digging the tunnels and laying the tracks that would connect Leimert Park — a Black middle-class corner of the city that was until recently ignored by all but the Black folk who made their lives there, sitting as it does so far south of the 10 — to the rest of the city. But the notion that South Los Angeles will be integrated into the rest of the city via public transit induces a bit of incredulity; my experience of transit in L.A. has always been one of a system designed to make travel along the city’s north-south axis as difficult as possible. The streets of the vast basin lying between the 10, the 405 and the 110 freeways are home to buses that are seldom on time, always overcrowded and never pleasant to ride. Dropped into the city with no prior knowledge of its workings, a newcomer might assume that Los Angeles public transit has been organized to dissuade rather than facilitate movement, particularly the movement of undesirable populations. They’d be right.

Photo essay: L.A. artists show us their Star Shots

I thought about this as the train’s construction began to converge on the neighborhood. If Leimert Park is a metonym for Black L.A., it’s because it tethers seemingly contradictory aspects of the city’s Black culture. Though the corridor that spills out from the plaza along Degnan Boulevard plays host to cultural institutions both old and new — places like Eso Won Books, artist Mark Bradford’s gallery/public art initiative Art + Practice and the legendary World Stage, where Horace Tapscott’s Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra got its start — the park also was host to a long-standing population of unhoused and drug-addicted people. These people were residents with as much claim to the neighborhood as the owners of the stately homes that line Degnan north of the plaza. This is not to say that their presence didn’t elicit anger or discomfort or annoyance among homeowners or that class prejudice was nonexistent; but the question of removing them from sight never felt like an option. But as the train approached, the neighborhood began squinting into the blinding lights of partition. Capital was bereft of an imagination that could make place for our unhoused neighbors, that could see the connection between them and the housed or illuminate their worth.

These days in South Los Angeles, it can feel as if there is no refuge for the kind of imaginative act that Purifoy envisioned via his junk art. Maybe he sensed the same. Maybe that’s why after decades of working to bridge the gap between social uplift and art, Purifoy retreated to Joshua Tree in 1989 and lived there until his death in 2004.

The activists undoing the racist gentrification of East L.A.

Out in Joshua Tree, you’ll see low-slung homes pockmarking the Mojave Desert valley and sometimes dotting the sides of the region’s craggy mountains. At night, cars speed along the desert roads, their headlights casting meager light against the dark or illuminating the tops of the chollas. The landscape feels both impossibly vast and enclosed, as if you’re wandering a globe whose top has suddenly been ripped off. In Joshua Tree, you feel that your life is minuscule, one part of an ecosystem that would not miss you if you were gone.

Around the time the decorative fence went up, I drove out to the open-air museum that Purifoy constructed during his 15 years in Joshua Tree. It was late May, and the scorch of the desert sun was beginning to chase away tourists like me. But I was determined to complete what by then had become an annual journey to the museum. I’d first come to Joshua Tree three years before on a writing retreat, and I’d found my subjectivity emptied by my encounter with the landscape. A week into what I intended to be a two-week stay, I wasn’t sure that I’d be able to remain another day by myself. Eventually, I stopped writing and spent my days driving up and down the Twentynine Palms Highway, dropping in at bars and clothing shops, more concerned with finding conversation than with purchasing anything. At a wine shop along the highway, the cashier — a Black woman who’d been working in South Los Angeles as an artist but found herself refugeed by increasingly onerous rents — suggested I drive to the museum.

What I found stunned me: a home surrounded by the accumulated results of Purifoy’s explorations into assemblage’s possibilities. There were massive structures like “Shelter,” a sunken building constructed from wood he salvaged from a friend’s destroyed house, the interior of which was lined with tattered rags. A walkway had been dug into the earth, inviting me to navigate the structure. It suggests something like a haven for the lost and discarded. The museum is filled with such structures — homes, classrooms, offices, an ersatz White House, all built from detritus Purifoy found and repurposed in the desert.

I am still not sure how a man can spend 15 years of his life surrounded by nothing but the artifacts of his mind’s own production. But I am compelled by the repetition of a motif: “home,” the arrival of spaces that might provide sustenance for whoever drives out into the Mojave. And I am drawn by the fact that every time I drive out, these homes are changed in some way, riven by the wind, warped by the heat, broken apart by some animal, human or otherwise. I am enchanted by the way these objects do not exist outside an ecology, by the way Purifoy’s art might inhere in how these discarded objects make music, say, when the wind rattles the metal roof of a ramshackle theater. One year, I went to find three crosses looming over me in the dusk. This year, I returned to find one of them damaged, missing its crossbar. Several times I found bird nests nestled in the crevices of a hubcap or bees pouring out of the hole in a propeller Purifoy made to stand upright. On my last visit, I watched a dog trot through the museum, sniffing and peeing on sculptures.

I’m entranced by how, out in the desert, Purifoy found a new life and meaning for that which is discarded. For me, what impresses more than the art objects themselves is that Purifoy concocted a space in which their violability demonstrates assemblage’s values. Walking its lonely expanse, you are witness to a perpetual rejection of exclusion.

Ismail Muhammad is a story editor at the New York Times Magazine. His work has appeared in the Atlantic, Paris Review, the Nation and other venues.