1

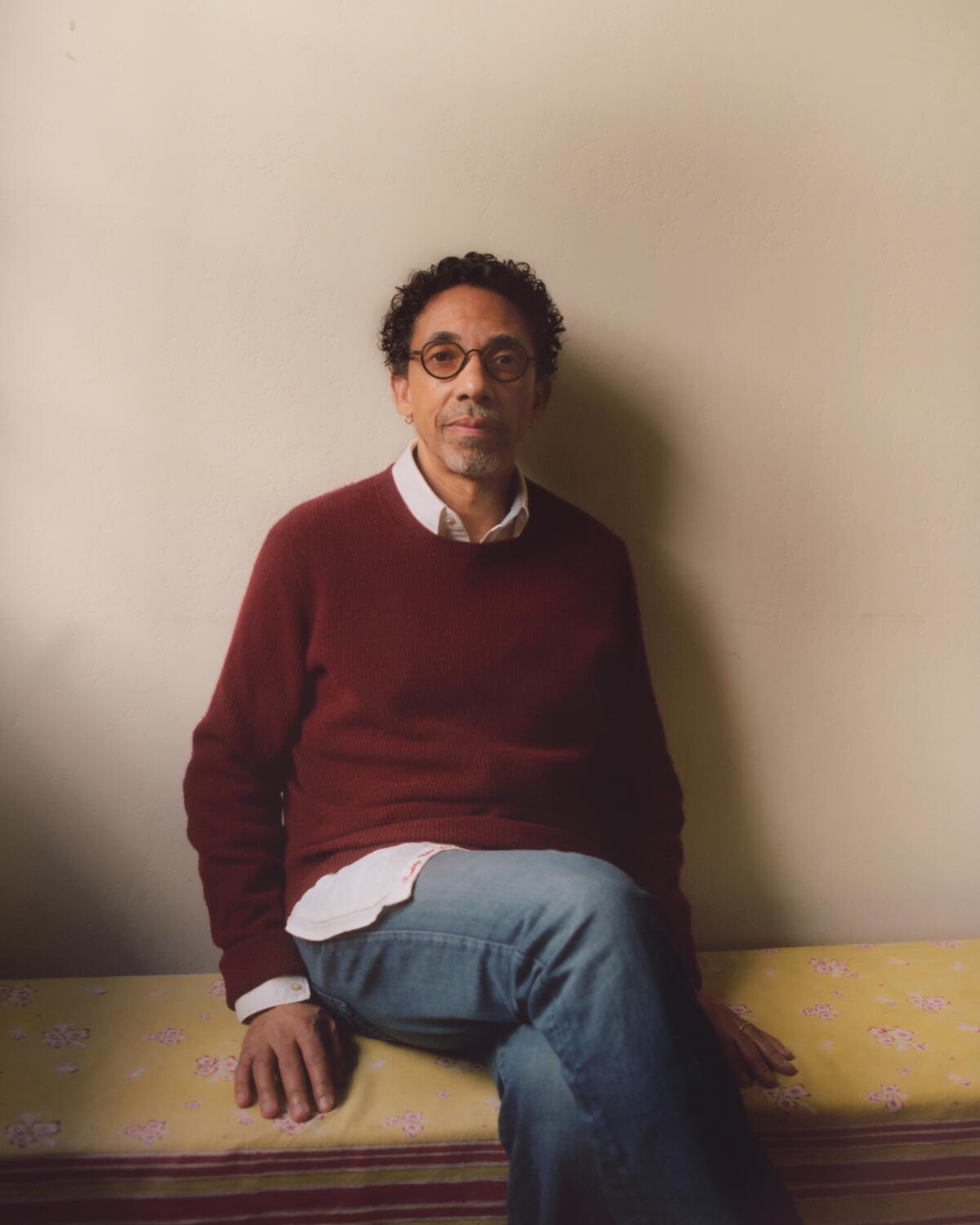

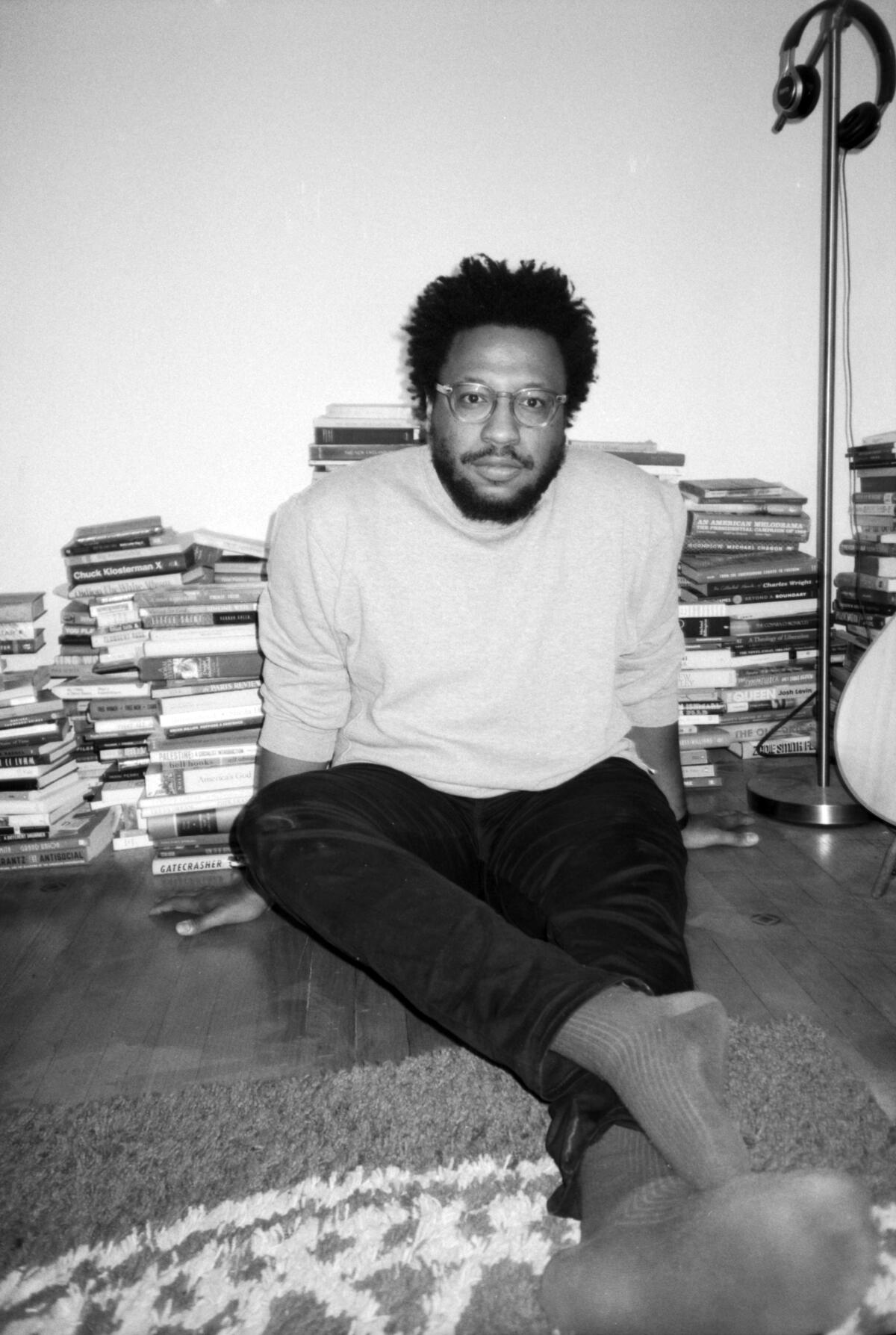

Historian/writer Robin D.G. Kelley

(Keith Oshiro / For The Times)

This story is part of our issue on Remembrance, a time-traveling journey through the L.A. experience — past, present and future. See the full package here.

Robin D.G. Kelley is, for my money, the great historian of our era. He has written groundbreaking works about, among other things, Alabama’s Communist Party during the Great Depression; the life of Thelonious Monk; and the visions of activists and thinkers from the African diaspora. On top of his work at UCLA — where he is a distinguished professor and holds the Gary B. Nash Endowed Chair in U.S. history — he issues a steady stream of limpid, persuasive, almost casually brilliant essays on politics, current affairs and cultural matters for Boston Review and other outlets. He keeps an eye on grassroots movements and on how maintaining a fertile, humane vision for the future creates new opportunities for radical action in the present.

In the year 2000, Kelley led the charge to reissue “Black Marxism,” a great, globe-spanning work of political history by one of his mentors, Cedric Robinson — successfully rescuing the book, then out of print, from near-obscurity. Since then, he has quite accidentally become the foremost authority on the late Robinson’s work and ideas. (“I did not want that,” he told me, sounding good-naturedly harried by the distinction.) Last year, after the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, among others, at the hand of police officers, and the global protest uprising that followed, UNC Press decided to reissue “Black Marxism,” which — as Kelley had predicted two decades earlier — had become more relevant than ever.

Kelley wrote a rousing foreword for the new edition of “Black Marxism” and is working on a book called “Black Bodies Swinging: An American Postmortem,” about how the protests of 2020 are connected to a long history of resistance.

———

Vinson Cunningham: I’ve been thinking about you and Cedric Robinson. I love how, in your foreword to “Black Marxism,” this new foreword, you always call him by his first name. It’s like: Marx and Engels and Cedric. That’s moving to me. It reminds me of one of my favorite essays, “Looking for Zora,” where Alice Walker goes to find Zora Neale Hurston’s grave. There’s a kind of artistic and intellectual lineage that’s not only about reading — there’s an affective aspect, something to do with feeling and familiarity. What is it about Cedric for you?

Robin D.G. Kelley: I was a student of Cedric’s. He was on my dissertation committee. I was in awe of him. Reading “Black Marxism” that first time in 1984, it just blew my mind and changed my whole orientation. Everything I do as a scholar can be traced back to that book — everything.

He passed in 2016, and with his passing, that’s the first time I ever really dug into his biography. His widow, Elizabeth Robinson, knew that I was close to Cedric intellectually and in other ways. She said, “Look, no one’s writing an obit. We can’t get an obit anywhere.” And I said, “I’ll write one.” I interviewed her, talked to her, and learned all these details that I was kicking myself. I was like, “If I had asked the question ... .” I didn’t ask the question because I’m a very shy person. I know that I’m in the public and stuff, but it’s a different thing.

Robin D.G. Kelley

(Keith Oshiro / For The Times)

VC: Why did you think the time was right for this third edition?

RDGK: I confess, I’m not the one who came up with the idea of putting it out again. It was UNC Press: Brandon Proia. In the midst of the protests — you had 26 million people on the street. He emailed me and Elizabeth and said, “Look, now’s the time to put out a third edition.” With the new foreword I wanted, one, to really tell Cedric’s story, to situate his intellectual biography to understand where this book came from. Two, to situate the book in relationship to the rebellion of 2020 and talk about it as a manifestation of a black radical tradition. So much of the conversation in political circles, coming out of or preceding the 2020 rebellion, all use terms like “racial capitalism” more than anything else. So I wanted to try to understand this movement, while also trying to clarify what Cedric meant by (a) Black radical tradition and (b) racial capitalism.

Justin Torres reflects on what happens when the one thing you’ve never lost finally disappears

VC: What are the difficulties in defining what racial capitalism means?

RDGK: The slightly more traditional Marxist scholars reject the idea that capitalism can actually be racial. They say, “Race is real. It’s a phenomenon. But it’s not really the fundamental one. It sort of gets in the way of what’s really the root of oppression: the reproduction of a capitalized class.” That’s class reduction. And then meanwhile, the so-called race reductionist position — you could call it Afro-pessimism lite — is that we’re just for Black people. They say, “The whole structure of Western civilization is based on anti-Blackness and anti-Blackness alone. And therefore, there can be no allyship, there can be no solidarity.” This kind of standoffishness, saying Black people need to just be for Black people, is not Cedric’s position at all.

The class reductionist versus race reductionist debate doesn’t really advance us. Cedric advances us by helping us understand how capitalism is based on racial regimes. So, for example, property may be capital, in the Marxist sense, but property values are dependent on things that are nonmaterial — that are ideological, or superstructural — like race. Capitalism is rooted in a civilization that is based on difference. This doesn’t at all mean that white people are the enemy, or that Black people are all victims, which I totally reject. It doesn’t mean that all white people benefit. It just simply means that capitalism is structured through difference.

I have made a point of the fact that Cedric was writing a critique of Marxism — but not a hostile critique. He wasn’t rejecting all of Marx and Engels’ ideas, but he felt like Marxism was a window to understanding forms of radicalism that neither Marx nor Engels, nor Lenin, and others, could really grasp. Ironically, some people have gone to a kind of extreme, saying, “There’s nothing in Marxism that’s useful. It’s just a white man making up some stuff, and Cedric is right.” And I’m like, “No.” I find myself actually becoming more of a Marxist in my defense of Cedric.

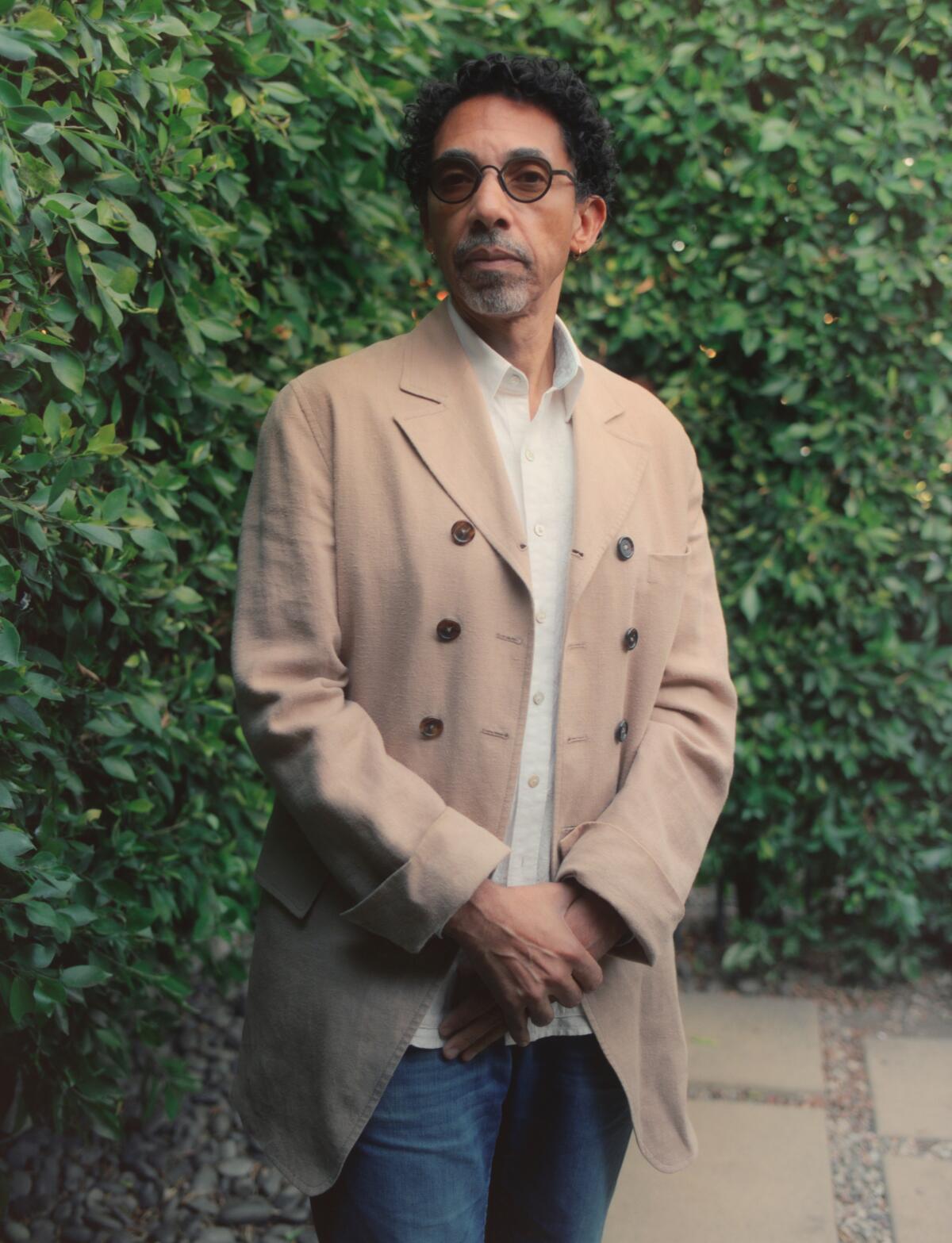

Writer Vinson Cunningham, in Brooklyn, will publish his debut novel, “The Party Year,” later this year via Hogarth/Random House.

(Alex Phillipe Cohen / For The Times)

VC: What do you view as your role as an intellectual? As you write “Black Bodies Swinging,” how do you make sure that what you’re describing is not only scrupulously true but also feeds into a politics that helps us both survive in the present and get somewhere more free in the future?

RDGK: That’s a great question. I feel like it’s not mandatory but it’s really important for me to be engaged in these movements, to make no pretense about some kind of dispassionate, detached objectivity. I think that we need to practice something that’s even better than objectivity. And that is, as you know, critique. Critique, to me, is better than objectivity. Objectivity is a false stance. I’m not neutral. I’ve never been neutral. I write about struggles and social movements because I actually don’t think the world is right and something needs to change.

As a historian, as a writer, I’ve got to try to be as critical as possible. I’m always trying to be truthful. As I write and produce this work, I learn things that we didn’t see before, but then, the work also reveals things that I failed to understand. And so to me, it’s always a process.

VC: Speaking of that kind of deep involvement, I would love to hear you talk about what California — and maybe Los Angeles, specifically — has meant for you in terms of your life but also in terms of your imagination of struggle.

RDGK: I came to California by way of Seattle in high school at the age of 15. It was in Pasadena. I was able to go to a state university where the tuition or the fees were $90 a semester. Cal State Long Beach. This was a time when we had a lot more Black students and brown students in college. I was involved with the Black student union. I had a part-time study group that was organized by the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party in Long Beach. That’s where I read Walter Rodney and Samir Amin and C.L.R. James — not so much in classrooms but in study groups.

Robin D.G. Kelley

(Keith Oshiro / For The Times)

A lot of the young people at the university and older people were working-class people — these were not the elites. In the ’80s we had the invasion of Grenada, we had the sanctuary movement, and the wars in Central America that were just driving Central Americans into Southern California; there was the anti-apartheid movement.

I ended up joining the Communist Workers Party at some point around 1983 or ‘84. I can’t remember when. [Jesse] Jackson’s 1984 campaign was really, really important. We had the Olympics come to Los Angeles in ’84. We organized a whole protest around the Olympics called Survival Fest. And we had a march down Wilshire Boulevard, MacArthur Park. There were like 10,000 people. Got no press, but 10,000 people marching down Wilshire Boulevard. Demanding what? Our demands were jobs, peace and freedom. It was a very exciting time.

VC: I’m glad you mentioned Jesse Jackson, because I have often lamented our resistance to his idea of a Rainbow Coalition. He was explicitly tying rural whites to Latino immigrants to Black working-class people, and putting forward the idea that we can only do this together. Solidarity was in the air.

RDGK: And, of course, where does Jesse Jackson get the idea of the Rainbow Coalition? It comes from Fred Hampton. He coined the term. The Black Panther Party, Illinois chapter, coined the term. And it’s through, specifically, a man named Jack O’Dell. I knew him. Jack was a former Black Communist, a close associate of Dr. King’s and then of Jesse’s, who bridged the generations and brought a left orientation to the civil rights movement. He was the one who introduced the Rainbow Coalition to Jackson. In our current moment, it’s hard to talk about things like a Rainbow Coalition politically. It goes against the white-ally idea, which I’m not really big into, where the ally is perceived to stand aside, standing there ready to be ...

VC: ... happy to help.

RDGK: Yeah, “happy to help.” The Rainbow Coalition’s more like, “We need to build a movement and we’re all in it.”

VC: And my freedom is a part of yours. I can’t get mine without you getting swept up too.

RDGK: Absolutely. The Rainbow Coalition notion really happened at the grass roots. It had less to do with Jackson and more to do with all the organizing on the ground. When Jackson ran for office, there was a vacuum because the Democratic Party establishment did not like him. The Black Democratic Party establishment did not like him. So that vacuum meant that all of these left-wing organizations basically swept in and became his advisors, Line of March, Communist Workers Party, the Communist Labor Party. I can name them because I was part of it. I was a member of the Communist Workers Party working on the Jackson campaign, all part of this underground of left-wing forces.

VC: You’ve said that in some ways the Black radical tradition comes together at “the crossroads where Black revolt and fascism meet.” What does fascism have to do with our moment, and what resources do we have to fight it?

Writer Vinson Cunningham.

(Alex Phillipe Cohen / For The Times)

RDGK: I would say — following the argument that Aimé Césaire made in 1950, and that Hannah Arendt made after that — that the roots of fascism are in colonial domination. Fascism is the power of the state, through coercion and through nationalism, to mark certain people through brutal suppression of rights, especially using emergency powers. It’s the idea that we’re in a state of war and that state of war is justification for abrogating any kind of civil liberties. In some ways, that’s what colonialism is.

VC: The constant state of war.

RDGK: For certain people, America has been fascist all along, and it just depends on what side you’re on. The vast majority of people can’t see fascism in a democracy where they can vote, and where they can walk freely. But for some of us, for undocumented people, for Black people, brown people, for Indigenous peoples especially, who’ve been put in concentration camps — all these fascist practices have existed in the United States from the get-go, from the beginning. What we see is fascism ebbing and flowing.

The abolitionist movements that erupted in 2020 are the movements that are dead set on ending fascism once and for all. “Fascism” is a word that we can’t be afraid of. I can’t say everything is fascist, but we can’t be afraid of recognizing the fascist elements that have been foundational to this country. Then we also can’t make the mistake of thinking of fascism as a particular, peculiar European thing, because part of Cedric’s point was that African American activist intellectuals were premature anti-fascists. They recognized fascism before a lot of white America did because they knew it. They knew it in the colonies, they knew it in the South, they knew it in their lives, they’ve seen it.

VC: In some ways, inviting the term “fascism,” and watching its ebbs and flows, necessitates internationalism and international thinking, right?

RDGK: Yes.

VC: In order to fight it, you have to fight it everywhere it exists and be in solidarity with — show love for — everybody who lives under it.

RK: Internationalism is the Raid for the cockroach of fascism. Because fascism, it’s always about using nationalism, and the nation, as a bludgeon to generate support for death policies, on behalf of death governments. For violence and repression and exploitation, internationalism is the antidote, always.

Vinson Cunningham, a staff writer and theater critic for the New Yorker, is the author of the forthcoming novel “The Party Year.”