Thirty years ago, when the Produce Hotel fell into disrepair, a newly formed nonprofit, the Skid Row Housing Trust, acquired and rehabilitated the turn-of-the-century building, restoring the brick facade and preserving 100 rooms for formerly homeless residents.

This story was repeated hotel after run-down hotel in the 1980s and ‘90s as homelessness advocates and civic leaders poured money and energy into saving the old single-room occupancy hotels in Skid Row — first built for itinerant railroad and agricultural workers — fearing that their collapse would force thousands onto the streets.

Now two generations later, livability and financial problems once again have thrown the SROs, which have tiny individual rooms and shared bathrooms, into disarray. Housing and health code inspectors have found clogged toilets, cockroaches, filthy hallways and broken windows in the Produce and similar, if not worse, conditions at dozens of other properties.

But this time, Mayor Karen Bass’ administration, nonprofit owners and service providers don’t want to save the SROs. Instead, they’d like to see them gone — demolished or gutted in favor of new buildings with private facilities for every tenant.

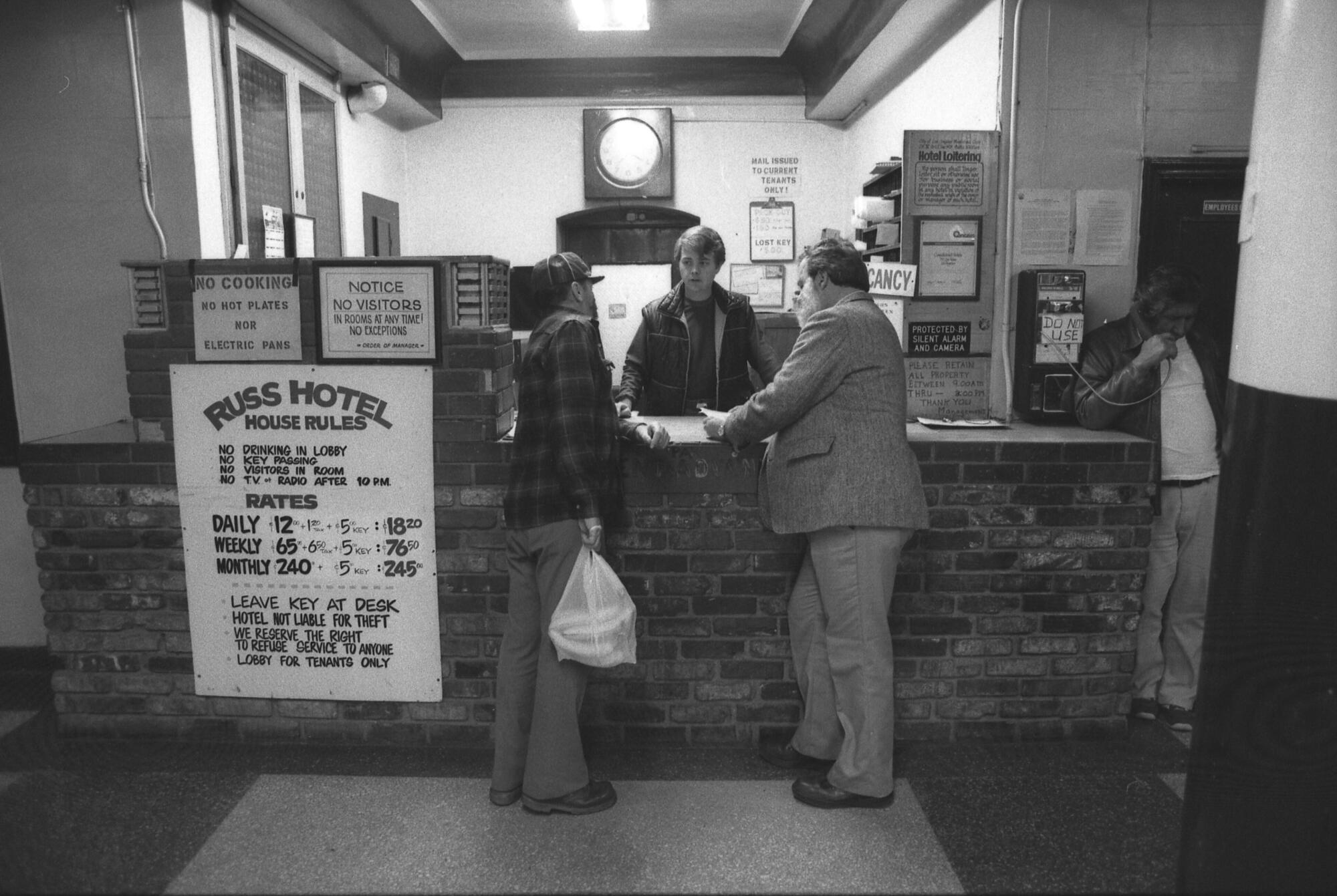

“Ideally, they need to be replaced,” said Carlos VanNatter, an executive with the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles. “These are old, turn-of-the-century buildings. They used to be flophouses. It’s not an ideal living situation for a chronically homeless person to be in.”

The demise of Skid Row’s SROs would mark a dramatic turning point in L.A.’s long battle with homelessness, ending an era of last-resort housing that began with the neighborhood’s creation in the late 19th century. A combination of dismal trends has led to a renewed crisis for SROs, which, along with other cheap hotels that have been converted to permanent housing, number about 7,000 units in Skid Row.

Housing subsidies have fallen far below the costs of operations. Changes in leasing that prioritize housing residents with severe mental health and drug addiction challenges have overwhelmed providers. And aging plumbing, heating, electrical and elevator systems have failed.

Given all that, vacancies have soared — despite the tens of thousands of people living on the street.

These problems exploded into view last year when Skid Row Housing Trust, the once heralded nonprofit founded in 1989 to preserve the Produce and other SROs, financially collapsed and fell into receivership. Of the 13 SROs owned by the trust, 10, including the Produce, already are being targeted for demolition or conversion into studio or efficiency apartments, with plans for the remaining three uncertain.

But despite the SROs’ deficiencies, the efforts to replace them are fraught with risk. Rebuilding the trust’s portfolio alone could cost nearly a half-billion dollars, displace, at least temporarily, hundreds of tenants and result only in a slight addition to the apartments available for homeless residents, according to city estimates.

Should redevelopment extend to SRO Housing Corp., a nonprofit that operates more than a dozen other Skid Row SROs and is facing its own struggles, the price tag and disruption could at least double.

Recently, The Times has been investigating Skid Row’s troubled housing providers, digging into the failures of nonprofits such as AIDS Healthcare Foundation.

The push away from SROs disturbs some advocates who see the move as expensive and counterproductive.

Ever since SROs were first built, there have been efforts to eliminate them by powerful interests who saw the buildings as promoting vice or occupying land too valuable to be used for the poor, said Pete White, executive director of the Los Angeles Community Action Network, a Skid Row-based nonprofit.

“You’ve seen this conversation before,” White said. “The solution can’t always be we’re going to knock it down and start over again. Because we don’t have the luxury to just knock it down and start over again.”

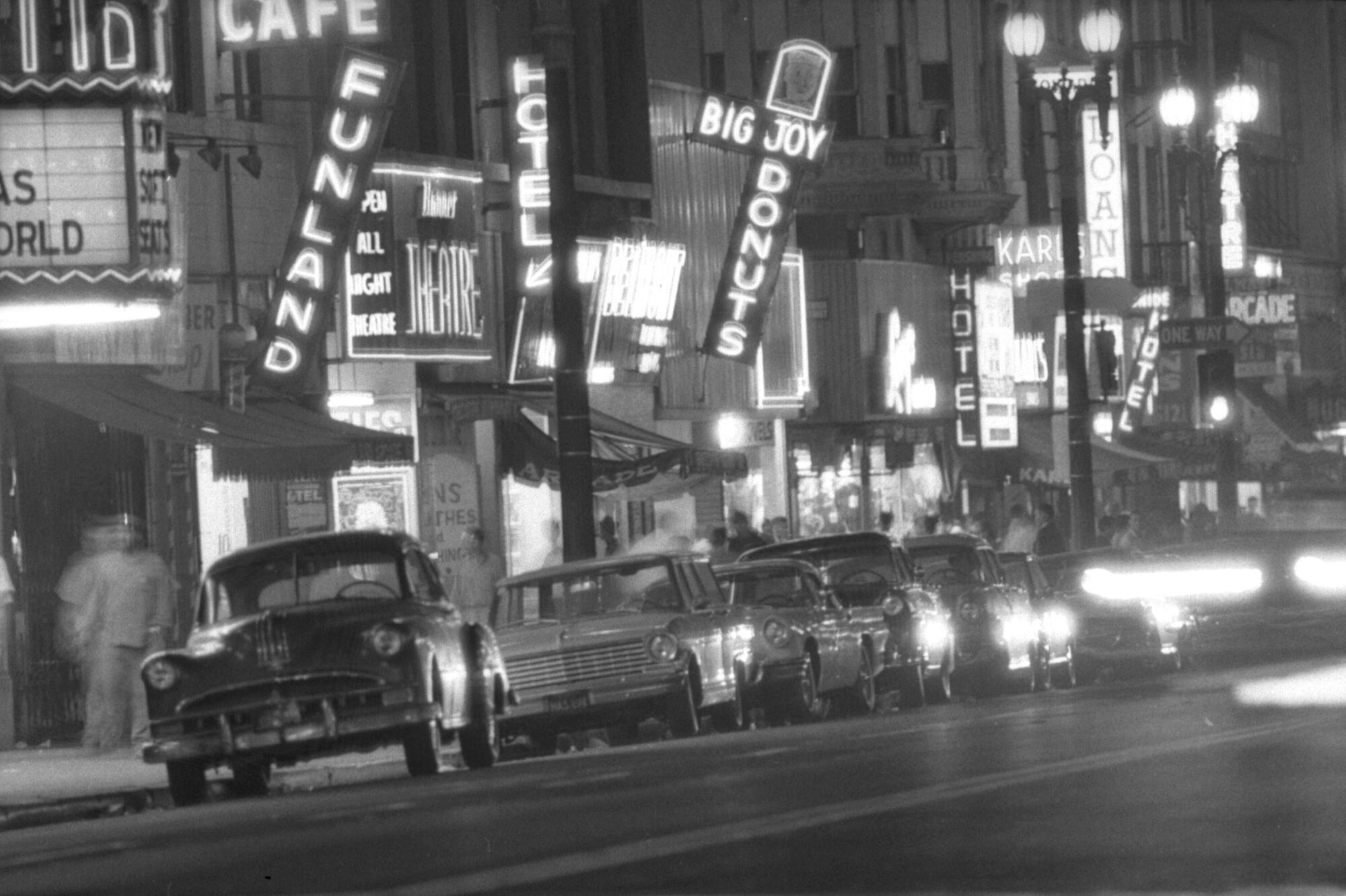

There’s no Skid Row without SROs. L.A.’s Skid Row emerged in the late 1800s just east of downtown at the ends of the cross-country railroads. Railroad workers, transient farmworkers and men just drifting west landed there. SROs, where rooms could be had by the hour, day or week, filled Skid Row’s 50-block boundaries with their legendary seediness depicted by writers Charles Bukowski and John Fante. Bars, brothels, warehouses and religious missions grew around the buildings.

By the late 1960s, Skid Row had 15,000 largely SRO housing units. Less than a decade later, half had been demolished and the neighborhood seemed destined to disappear, according to a Skid Row history produced by UCLA’s Department of Social Welfare.

But city officials soon changed course. They began what became known as a “containment policy” for Skid Row. Leaders believed they needed to have low-cost housing and social services centered somewhere in the city, and started taking steps to keep the SROs alive. In doing so, they also sought to keep impoverished, drug-addicted and mentally ill people inside the neighborhood.

“Maintaining and preserving those SROs in Skid Row was about maintaining and preserving other parts of the city — keeping SROs and the people who lived in them away,” said Deshonay Dozier, an assistant professor of cultural studies at Claremont Graduate University who specializes in the history of Skid Row.

City leaders provided the initial funding for SRO Housing Corp., which was founded in 1984. Skid Row Housing Trust started five years later.

Both nonprofits received widespread praise for their rehabilitation work.

“It is clean, safe and honest,” Bernard E. Harcourt, then a University of Chicago law professor, wrote of the Produce in 2004, a decade after it reopened. “There are no bad smells — so common in homeless missions and housing. No trash or litter. It is inviting.”

Still, redevelopment pressures, driven by manufacturing and wholesaling interests and ultimately high-end development on the outskirts of the area, never went away. In the mid-2000s, the city doubled down on preservation, passing a new law to maintain as permanent housing SROs and other cheap hotels that had turned into full-time residences. A legal settlement provided even more protections for buildings in Skid Row, requiring replacement of SROs torn down or converted.

While they continued their acquisitions, SRO Housing Corp. and Skid Row Housing Trust began turning some into efficiency apartments, a process that often resulted in the demolition of units or whole buildings to make space for those with private bathrooms.

The nonprofits also moved beyond preservation to become developers of homeless housing. These new buildings not only offered residents more privacy but also gave the organizations a financial boost they needed to paper over mounting losses at their SROs. But it hasn’t been enough.

After the trust’s longtime leader left in 2018, the organization cycled through chief executives who put forward increasingly desperate moneymaking schemes. As the trust announced its collapse last February, one building had been shut down due to arson, another had been empty for years after a failed redevelopment and the remaining 27 were largely abandoned with sporadic security, cleaning crews and case workers for 1,500 tenants. A quarter of the trust’s units were deemed uninhabitable.

The Skid Row Housing Trust was a model for nonprofits housing homeless people in Los Angeles. Behind the scenes, it was imploding — leaving tenants in squalor.

Unlike the trust, SRO Housing Corp. has had stable leadership, with its CEO Anita Nelson in charge for two decades. Yet the nonprofit’s financial picture also has been dire. In 2019, according to an internal report, 10 of its 15 SROs were operating at a loss. Money woes only worsened through the COVID-19 pandemic as rent collection slowed and property insurance costs skyrocketed, Nelson said.

“We were just struggling keeping our doors open,” Nelson said.

Building conditions have deteriorated. Five SRO Housing Corp. properties are so damaged that city housing officials put them in a program reserved for problem landlords. Tenants receive rent reductions and can pay their monthly rent to the city, which holds the money in escrow until the landlord makes repairs.

In a tidy 11-by-15 room on the second floor of the 38-unit Haskell hotel, one of four SRO Housing Corp. buildings on the 500 block of Wall Street in Skid Row, Micah Ray can’t ignore what’s around him.

No one leaves any food in the shared kitchen because it would be stolen, Ray said. During the day, he burns incense and keeps his window open to dispel the smell of urine and feces from the hallway. Drug dealers and sex workers squat in vacant units. Ray uses a mobile shower set up in the street for unsheltered residents rather than the shared facility on the floor above him.

“These showers, you can’t imagine coming out of one clean,” Ray said.

A photographer and artist, Ray, 55, became homeless in 2020 after a cancer diagnosis, living in a tent in Koreatown, a hotel-turned-shelter and a tiny home village, both in Westlake, before moving into the Haskell in June 2022.

In the building he wears what he calls “a uniform” of old sweats so he doesn’t stand out.

“I don’t want to compare it to prison, but there you want to keep yourself clean and out of trouble,” Ray said. “The exact same thing is happening here in this building.”

Twenty-two Skid Row Housing Trust tenants lost their homes in a fire in February. Residents remain scattered and scarred, unable even to recover most of their possessions.

Of all the challenges facing SROs, the most immediate one, public officials and providers say, is the mismatch between federal housing vouchers and the cost of operations. Ann Sewill, the head of the city housing department, told council members last fall that in the former trust properties, the subsidies, which mostly come from old programs that are being phased out, pay about $700 per unit per month while the price tag to run them was $1,000.

The negative cash flow makes it harder to finance repairs, resulting in a financial death spiral as rooms go offline. As of last month, 30% of the units in the 21 trust buildings still under receivership were empty, according to a recent report from the receiver.

Deepening the crisis, providers said, is a decade-old change to leasing practices. The region’s homelessness authority implemented a coordinated entry system for subsidized SROs and other permanent housing that prioritizes chronically homeless residents, often those with significant addiction and mental health challenges. The trust and SRO Housing Corp. have complained that bureaucratic delays left rooms vacant for too long and, once rooms became filled, the system concentrated too many disorderly people in their buildings.

Some public agencies already have turned away from SROs. In 2014, L.A. County’s Department of Health Services began placing its homeless clients in the buildings through a rent subsidy program, but reversed course four years later. Leepi Shimkhada, the department’s deputy director in charge of housing, said clients needed private bathrooms and kitchens to be housed successfully.

“We found early on that people were not thriving in those locations,” Shimkhada said.

Last year, the city asked the California Housing Partnership, a nonprofit affordable housing consultant, to develop a plan for a dozen of Skid Row Housing Trust’s oldest properties that, due to their age and conditions, were unlikely to find other nonprofit landlords willing to take them over.

At first, the consultants expected to recommend maintaining the buildings. But as they dug into conditions and spoke with service providers, they determined that doing so would be throwing money at an unworkable housing model, said Paul Beesemyer, the partnership’s managing director. They proposed demolishing the SROs and building efficiency apartments instead.

“The starting assumption was not to do the thing that seemed on its surface like it would cost the most money,” Beesemyer said. “But once you go into a circa-1915 building, rip out virtually every wall to reconfigure and create a new building within the shell of an old, you’re getting into a price point that looks very much like building new.”

It’s not just Skid Row Housing Trust and SRO Housing Corp. that have had problems operating SROs.

In December 2021, for-profit developer Baron Property Group reopened the 600-unit Cecil Hotel, notoriously the former home of several serial killers on the boundaries of Skid Row, as the city’s largest SRO. The developer has struggled to fill the rooms, and its formerly homeless tenants say they’ve felt abandoned as mold grows, violence persists and elevator service in the 15-story building remains spotty. Baron put the Cecil up for sale this month.

Starting in 2017, AIDS Healthcare Foundation, the world’s largest AIDS charity, began buying up SROs with the same stated mission as the trust and SRO Housing Corp. decades ago: rehab and operate them at a cost even the most impoverished could afford. The L.A.-based foundation, which makes more than $2 billion in revenue annually, has spent nearly $200 million on 16 properties in and around Skid Row and poured an additional $30 million into renovations and repairs. It charges rents as low as $400 a month and largely avoids public subsidies.

Foundation leaders tout they’ve increased occupancy by almost 200%, meaning almost 1,000 more people are off the streets. But a Times investigation last year found deplorable conditions in their buildings, with, in some cases, tenant complaints and crime surging after the nonprofit took over.

A Times investigation has found that many of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation’s more than 1,300 residents live in squalid conditions, with dozens under the threat of eviction.

At the same time, the foundation has said it’s lost more than $15 million over six years on operations across its portfolio. And that’s without providing social services, which researchers believe is essential when serving a chronically homeless population, but executives have rejected as too costly.

“To get this many people housed is viable and is beneficial,” foundation President Michael Weinstein said last fall in a deposition from a class-action habitability lawsuit filed by foundation tenants. “I’m saying that the amounts of money that we have lost and had to continue to invest, you know, if you look — if you’re talking about economics from the point of view of attracting other people to do it, then it would not be attractive.”

Two miles from Skid Row in Westlake, Holly Benson, the president and CEO of nonprofit developer Abode Communities, has spent years trying to figure out what to do with the Clark Residence, a 152-unit SRO it has owned since the early 1990s.

On the surface, the Clark should be able to avoid some of the problems faced by Skid Row SROs. Built in 1914 as a YWCA, the stately brick building is on the National Register of Historic Places. Rooms average $400 a month, but because they’re not directly subsidized with homeless housing vouchers, Abode chooses its own tenants and there are fewer with severe addiction and mental illness.

Still, around 20% of the Clark’s rooms are vacant and the nonprofit has had to spend nearly $2 million to cover budget shortfalls in recent years, Benson said.

She now is struggling to cobble together public funding programs to convert the property to efficiency apartments.

“There’s not a ready solution to get from here to where we repurpose these buildings,” Benson said.

The city’s redevelopment plan for the dozen Skid Row Housing Trust properties reveals these challenges. At an average of $500,000 per unit, the proposal would cost $428 million and result in a net increase of just 47 apartments over the current 809 rooms. Price tag aside, existing tenants would have to vacate while the properties were torn down or gutted.

Sewill, the city housing director, defended the plan as no different from what the trust already was doing in converting its SROs to efficiencies. She noted that the proposal calls for rebuilding the portfolio over the next seven years to spread out costs and avoid disruption.

“We’re trying to make sure that we’re not back here in receivership again,” Sewill said. “Doing the whole redevelopment is one way of making sure that you have a building that meets the needs of the tenants, but it’s also going to be the least expensive to operate and maintain for a very long time.”

But some point to city failures as reason to doubt that the redevelopment plans will benefit residents. The city has long been aware of the financial challenges faced by the two nonprofits and is responsible for ensuring habitable conditions. It never should have allowed circumstances to deteriorate to such an extent, said White of the Los Angeles Community Action Network.

Combined with the history of efforts to demolish Skid Row SROs for private gain, White lacks trust that the city can manage a massive redevelopment plan.

“I am 100% skeptical that without strong tools, strong controls, that this could become an opportunity to eliminate the community of Skid Row as we know it,” he said.

The city expects to acquire the dozen trust properties this spring, boost their federal rental subsidies and then spin the buildings off to developers who would receive fast-track approval for the local portion of the redevelopment cost. City officials, Sewill said, have strong interest in ensuring success, not only to support chronically homeless residents but also to protect the tens of millions of dollars it’s investing into the trust portfolio.

“We’ve got a whole unit of people that are working on it,” she said. “We’ve put the capacity into it. We certainly have the incentive. This is our largest single concentration of supportive housing in the city.”

After Skid Row Housing Trust financially imploded earlier this year, the L.A. City Council is close to approving $40 million to stabilize 1,500 formerly homeless tenants.

White and others say they believe that money should instead go into fixing up the SROs, which they argue is cheaper and faster.

Last year, SRO Housing Corp. received $45 million from a state housing preservation program to upgrade plumbing, structural and electrical issues at three SROs for $222,000 per unit, with the work expected to extend the buildings’ lives for decades.

Nelson, its CEO, said she pursued the funding to rehabilitate, rather than redevelop, her properties because that’s what was available.

“If you said, ‘Anita, the money’s out there, rental subsidies are out there, do you want to keep these 13 properties as SROs or convert them to efficiency units?’ Of course, I’m gonna say convert them to efficiency units,” Nelson said. “But that’s not reality. What we have at hand is a housing crisis that is growing. People need housing. We have housing stock, which is better than being in a tent.”

Ray, the tenant at the Haskell, said he’d rather be in his SRO than homeless. He’s still trying to do everything he can to leave.

Residents who’ve lived in SROs for two years can apply for a Section 8 voucher that would allow them to find an apartment on the private market. Ray was a few months short of qualifying but successfully pushed for special consideration.

The mother of Ray’s teenage son died from cancer last month and Ray wants to take custody. Ray couldn’t imagine living with his son at the Haskell. In the few times his son visited, Ray stood guard when the boy needed to use the bathroom because he was worried about his safety.

Ray feared that he would have become depressed or turned to substance abuse if he hadn’t gotten the voucher.

“Things were really starting to feel desperate,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.