A Times investigation has found that many of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation’s more than 1,300 residents live in squalid conditions, with dozens under the threat of eviction.

After her eviction, Alisha Lucero returned to her apartment to find her belongings thrown away.

Gone were Lucero’s passport and her recently deceased brother’s high school letter jacket. Lucero said she couldn’t get into her car because her landlord, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, had trashed her keys. She was wearing the only clothes she had left.

For the next two years, Lucero lived on the streets where she said she was raped and beaten while her mental health spiraled. At times, Lucero slept in a tent steps from her former residence, the Madison in Skid Row.

“What they did to me was unjust, was brutal, was inhumane,” said Lucero, 44, speaking about her eviction. “They literally ruined my life.”

The foundation evicted Lucero and scores of other tenants in disputes over unpaid rent. At the same time, it was making public statements about the dangers of forcing people from their homes. On social media during the COVID-19 pandemic’s darkest days, the foundation put the stakes bluntly.

“Evictions kill,” the foundation said.

Such contradictions between the AIDS Healthcare Foundation’s vocal pro-tenant advocacy and the harsh conditions depicted by its residents have characterized the charity’s six-year foray into providing housing. With $2.2 billion in annual revenue drawn largely from its pharmaceutical business, the Los Angeles-based global AIDS nonprofit has transformed itself into one of the nation’s most prolific funders of tenants’ rights campaigns and one of Skid Row’s biggest landlords.

Recently, The Times has been investigating Skid Row’s troubled housing providers, digging into the failures of nonprofits such as AIDS Healthcare Foundation.

Under the direction of co-founder and President Michael Weinstein, the foundation has spent more than $300 million sponsoring rent control ballot initiatives in California and buying apartment complexes across the country, including more than a dozen in Los Angeles, mostly old single-room occupancy hotels.

At rallies, protests and news conferences, in newspaper advertisements and on social media, the foundation has billed itself as a white knight in the battle against homelessness. It pledged to manage its portfolio of properties at a fraction of the cost of government-subsidized projects.

“Elected officials would be wise to replicate AIDS Healthcare Foundation’s urgent, cost-effective model to build more low-income and homeless housing,” the foundation said on social media last year. “Lives hang in the balance.”

But a Times investigation has found that many of the foundation’s more than 1,300 residents live in squalid conditions with dozens under the threat of eviction. Roaches and bedbugs infest rooms. Electricity, heating and plumbing systems fail. Elevators malfunction. Code enforcement and public health complaints at foundation buildings are more than three times higher than those owned by other Skid Row nonprofits. Meanwhile, the foundation has evicted tenants over debts of just a few hundred dollars, eviction records show, while suing nearly 70 others for back rent in small claims court.

In a statement to The Times, foundation General Counsel Tom Myers said the organization has spent tens of millions of dollars renovating and repairing its properties. Myers said the foundation has increased occupancy by nearly 200%, meaning almost 1,000 people are off the streets who otherwise wouldn’t have been. The foundation’s problems, he said, are similar to those faced by other Skid Row landlords: operating old buildings while serving a troubled tenant population without sufficient support from the city. The foundation did not provide answers to a detailed list of questions from The Times.

“The perfect cannot be the enemy of the good,” Myers said. “Six people die on the streets of Los Angeles every day.”

The Times reporting is based on interviews with nearly 30 current and former AIDS Healthcare Foundation residents, more than a half-dozen visits inside foundation properties, accounts from former employees and thousands of local housing department, code enforcement, public health, public safety, coroner and court records. The Times also reviewed more than a year of foundation emails, incident reports and other internal records detailing its housing programs.

1

2

3

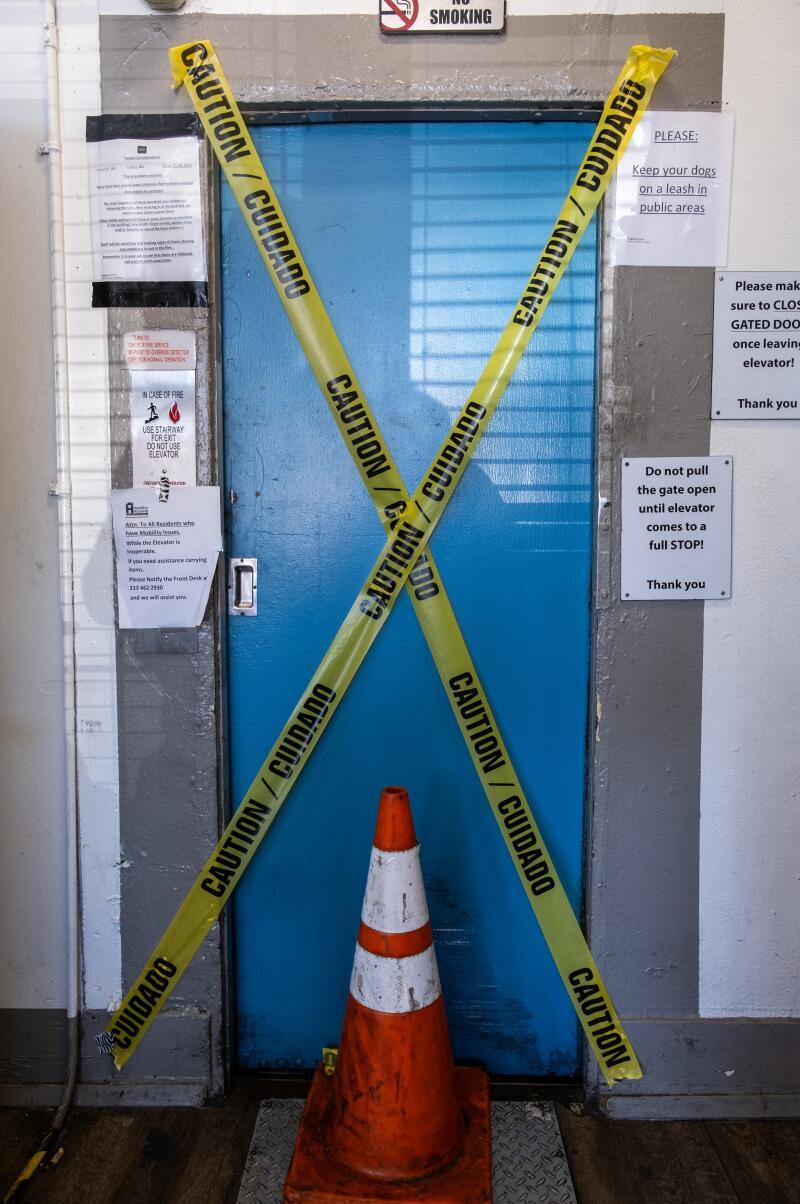

1. Caution tape covers the elevator inside the Madison in August when it was out of service for three weeks.

2. and 3. Markings that appear to be cockroach droppings on a tenant’s closet door in the Baltimore Hotel. (Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

The picture that emerges is of a well-funded organization struggling with the contradictions and burdens of simultaneously trying to serve as tenant advocates and provide non-subsidized housing in Skid Row without prior experience in the field.

Within foundation buildings, this has led to disregard and disorder. One tenant’s dog was scalded to death after a radiator exploded. A legally blind tenant fell more than 12 feet down an open elevator shaft. A third resident nearly died after he was shot in his doorway, an incident that led to an attempted murder charge against a fellow tenant whose documented history of violence had earned him the nickname “Killa.”

Last month, a Times reporter observed eviction notices posted on 14 residents’ doors on just one of the six floors in the foundation’s Baltimore Hotel. And while the foundation has praised a new city law that requires landlords to disclose such notices publicly, saying it helps “spot disturbing eviction trends,” the charity hasn’t reported any from the Baltimore, city Housing Department records show.

‘Like inhumane conditions. People’s units were falling apart.’

— Julia Coy, a former employee who worked daily in the King Edward, Baltimore and Madison

Many residents, especially in the Baltimore and other Skid Row properties, have severe disabilities, drug addiction and mental health problems. Fifty people have died in foundation buildings, according to coroner reports, with drug use the most frequent cause.

Unlike other nonprofit landlords who rely primarily on government subsidies, the foundation doesn’t provide its tenants with counseling or other supportive services, citing the cost. Instead, with the exception of two smaller buildings outside Skid Row leased to service providers, the foundation encourages residents to seek outside help.

This approach has left gaps in care. Two years ago, when foundation employees raised alarms about tenants’ suffering, executives declined their requests to offer more assistance.

Carlos Brum, who had been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress and anxiety before moving into the Baltimore in 2019, said his mental health has deteriorated amid violence, outbursts from neighbors, vermin and plumbing failures.

“Living here, I have never felt so subhuman in my life,” said Brum, 44. “It never gets better. It only gets worse. I’m sick of it.”

Weinstein, a 71-year-old New York City transplant, started the foundation in 1987. Now headquartered on the 21st floor of a Hollywood high-rise, it’s become the world’s largest AIDS nonprofit, with clinics and advocacy programs in 45 countries and 1.9 million patients under its care. Angelenos drive by the charity’s billboards promoting testing for sexually transmitted infections and condom distribution that have warned “Gonorrhea Alert!” “Syphilis Explosion” and, most recently, “Just Use It” above a condom unfurled on a banana.

Using a special federal program for healthcare organizations that serve indigent populations, the foundation is able to buy HIV/AIDS drugs at a steep discount and charge insurance companies the full price when dispensing them to patients. Financial statements show the foundation’s network of 62 pharmacies earned $1.9 billion of the charity’s $2.2 billion in total revenue last year, making it larger than health nonprofits such as Planned Parenthood and the American Heart Assn.

These bountiful coffers allowed Weinstein to expand the foundation’s mission.

Weinstein has long argued that real estate capital and luxury developments were destroying Los Angeles neighborhoods by displacing residents.

Six years ago, the foundation started a tenant advocacy group called Housing Is a Human Right and launched statewide political campaigns.

In 2018 and 2020, the foundation poured a combined $64 million into ballot measures to expand rent control across California, campaign finance records show. Opponents, largely corporate landlords, dropped $160 million to defeat the efforts, winning each time by 20 percentage points. The foundation is now sponsoring a third initiative for the 2024 ballot.

In 2017, the foundation began buying single-room occupancy hotels, motels and small apartment complexes. Weinstein, often critical of the city’s slow, bureaucratic response to homelessness, said he would house people faster and more cheaply.

‘Living here, I have never felt so subhuman in my life.’

— Carlos Brum, tenant of the Baltimore

The foundation charged some of the lowest unsubsidized rents in Los Angeles: around $400 a month for its century-old, single-room occupancy hotels in Skid Row. Part of its pitch was that, unlike government agencies and other nonprofits housing low-income tenants, the foundation would focus on renovating properties rather than building new ones, which can take years and exceed $1 million per unit to construct.

“Our idea at the AIDS Healthcare Foundation has always been not just to tell them but to show them,” Weinstein said at a 2018 panel hosted by U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), a longtime ally.

Under the banner of the Healthy Housing Foundation, the nonprofit has spent $178 million snapping up 15 properties in Los Angeles, now managing nearly 1,500 units with an additional 467 under development. The foundation’s footprint extends outside L.A., with an additional $66 million spent on buildings in Georgia, Florida, New York and Texas.

The charity’s tenant rights arm touts the renovation model, calling it a “massive success” in a December 2022 post on its website.

When the foundation opens its properties, it publicizes the installation of laminate flooring, fresh coats of paint and other upgrades.

It does not mention what city, county and internal records show: broken plumbing, faulty electrical systems and elevators and pest and mold infestations.

Circumstances are the worst in the Baltimore, King Edward and Madison, three single-room occupancy hotels in Skid Row that were among the foundation’s first purchases.

All are about 100 years old — the King Edward has 150 rooms, the Baltimore and Madison each have around 200 — with most residents sharing common bathrooms on each floor.

“The buildings were terrible, absolutely terrible,” said Julia Coy, a former employee who worked daily in the three properties. “Like inhumane conditions. People’s units were falling apart.”

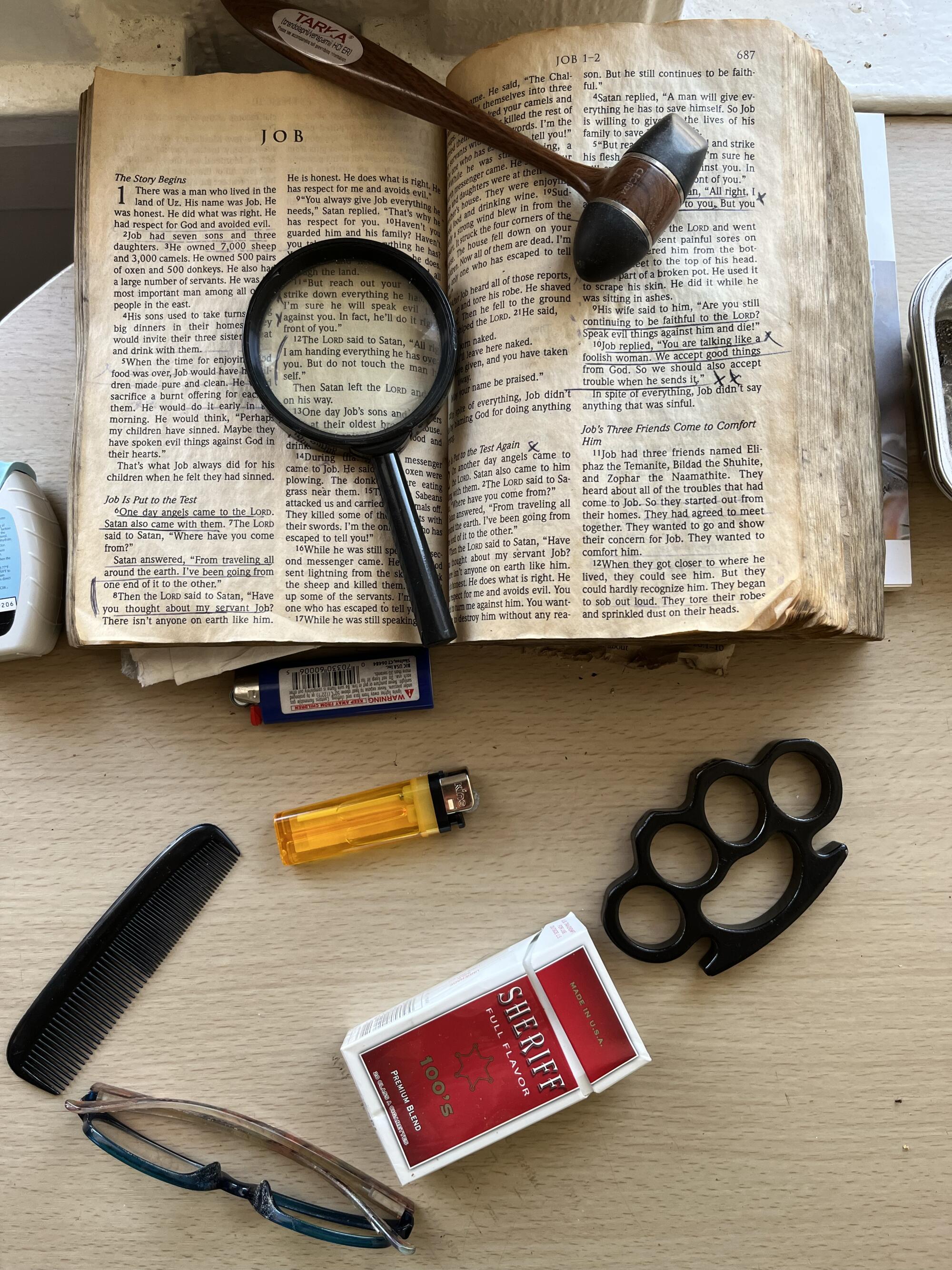

In late December 2021, the heat had been out all week in the King Edward when Blaine Heffron got ready to drive overnight for Lyft. He poured bottled water into a bowl for his 2-year-old pit bull, Caya — the building’s chalky tap water wasn’t good enough for his beloved rescue dog — and settled her in her crate.

The foundation had been working on repairs to the building’s boiler. While Heffron was gone, the radiator in his room exploded, filling the room with blistering steam and killing Caya in her crate, according to Heffron and a Fire Department incident report.

Upon returning, Heffron couldn’t face the scene and was temporarily relocated elsewhere in the King Edward. It took four days for Caya to be removed, text messages between Heffron and a property manager show.

In the interim, Heffron reluctantly went into his room to see whether any possessions were salvageable. Sitting on his still-sopping mattress with tears streaming down his face, Heffron said he stared at Caya’s body and apologized over and over again.

“I felt like I was robbed of time with my best friend,” said Heffron, 36. “It just sickens me.”

Heffron hasn’t received compensation for what happened. He’s considered taking the foundation to court but felt intimidated. When Heffron fell behind on rent earlier this year, the foundation taped a notice to his door threatening to evict him.

“I don’t know what I’m doing, and I know I’m going up against a multibillion-dollar organization,” he said.

Blaine Heffron, 36, holds the leash of his former dog, Caya, who he said was killed when the radiator in his room at the King Edward exploded in 2021. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times; photo of Caya from Blaine Heffron)

‘I felt like I was robbed of time with my best friend. It just sickens me.’

— Blaine Heffron, on his dog, Caya

The foundation did not respond to questions about Caya’s death or other specific habitability issues in its buildings. According to Myers and court filings, it’s poured nearly $30 million into renovations and repairs. Some, the foundation said in court filings, have taken time to complete because of difficulties finding replacements for century-old parts and delays caused by permitting and the COVID-19 pandemic.

In several buildings, the rate of city code complaints increased after the foundation bought them, a Times data analysis shows. The most extreme of those, the King Edward, had only six complaints in the five years before the foundation purchased it in 2018, but drew 32 in the five years after.

Complaints, which typically come from aggrieved tenants, don’t always result in violations. But at the King Edward inspectors have found exposed electrical wiring, painted-over fire sprinklers, missing smoke detectors and inoperable doors and windows. Internal foundation photos from 2020 show a private bathroom covered in what appears to be black mold.

Sworn declarations in a class-action lawsuit over conditions at the Madison describe nests of cockroaches filling rooms, hallways and communal bathrooms and feral cats roaming the property. One tenant said that after his neighbor died in 2019, maggots came through a hole in the wall.

Plumbing is among the buildings’ biggest problems. The Madison has had at least five failures so severe that water cascaded down the hallways and stairwells, said Mark Dyer, the foundation’s top real estate executive, in a recent deposition from the class-action case. Dyer blamed residents for the flooding, saying in one instance an angry tenant poured powdered concrete down their sink and then turned on the faucet, filling the pipes with cement.

A video taken by a resident shows a similar internal flood at the Baltimore last summer.

A video by tenant George Handy shows flooding at the Baltimore in summer 2022.

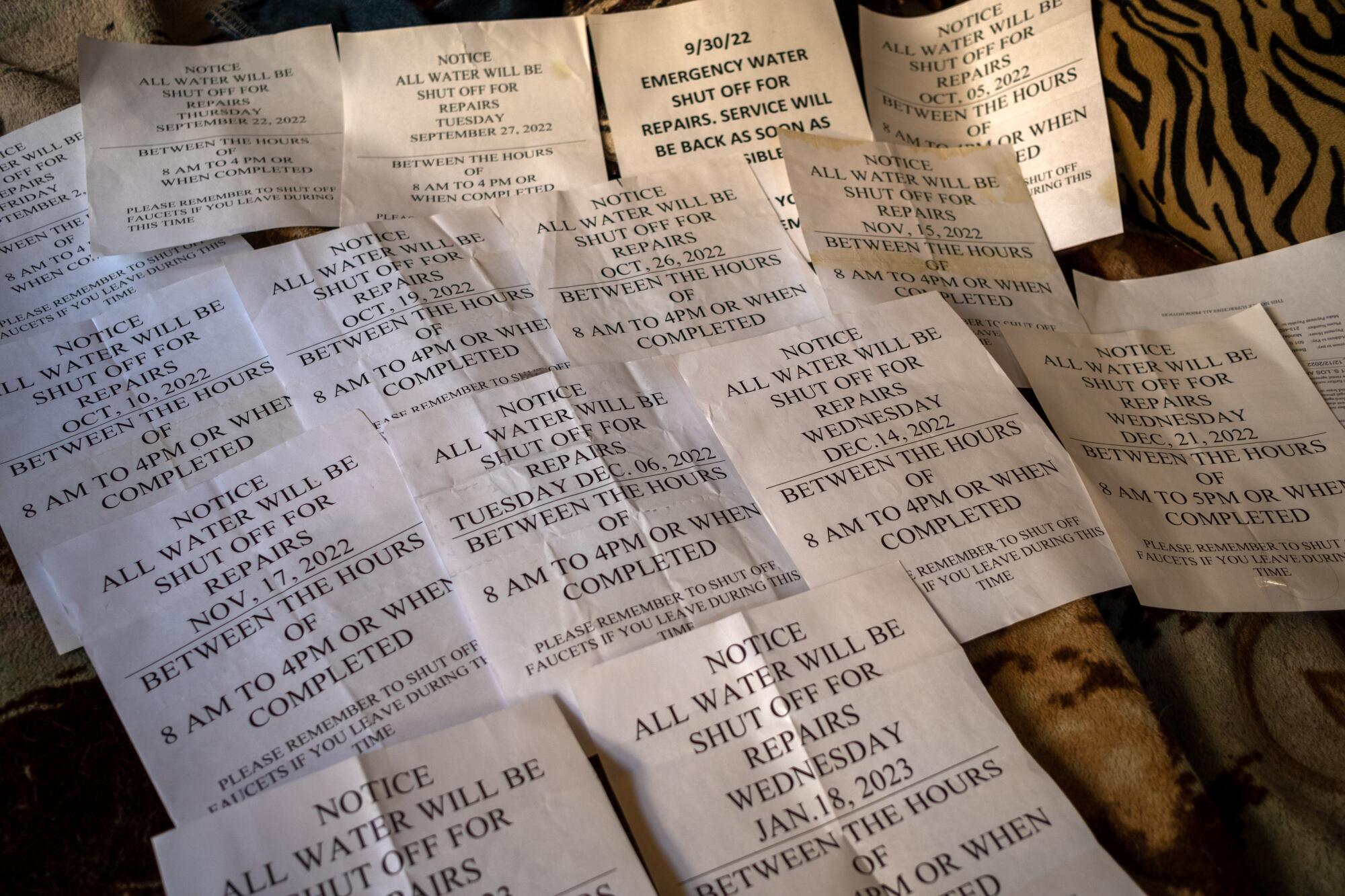

Brum said the water in the Baltimore has been shut off at least 30 times since September 2022 when he began collecting notices management posts. When that happens, residents are forced to defecate in wastebaskets in their rooms and then, he said, take “the walk of shame” to deposit their feces in hallway trash rooms.

Brum has worked as a Crypto.com Arena vendor and said co-workers complained about how he smelled.

“Do you know how belittling that was?” said Brum, who is lead plaintiff in a pending class-action lawsuit over conditions at the Baltimore. “I am doing the best with what I have to work with. How are we supposed to improve our circumstances when they’re cutting off some of the most basic tools: running water?”

Myers, the foundation’s general counsel, did not answer questions about conditions at the Baltimore, but in court filings the foundation has asked a judge to throw out Brum’s suit.

At the Madison, the foundation says it’s invested more than $7 million into upgrading the electrical and plumbing systems, replacing the boiler, installing security cameras and adding dumpsters.

“The Madison does not claim to be immune to issues that are to be expected in a 100-year-old building,” a foundation attorney said in a September filing in the Madison class action.

Myers cited depositions where city inspectors say the foundation responds to tenant complaints and refer to the Madison as “decent” and “safe.”

Robert Galardi, the head of the city’s code enforcement division, said in a deposition that he believed the foundation had improved conditions within the Madison. But he said the foundation’s inexperience shows, with repeated stumbles complying with permitting rules and managing newly housed tenants because it doesn’t provide social services.

“I don’t believe that they were prepared to deal with those extra attentions that these folks needed for moving off the street and into the buildings,” Galardi said.

Crime statistics show serious incidents becoming more frequent at the Baltimore, King Edward and Madison after the foundation bought them, far exceeding a general rise in crime reported in Skid Row at the same time, a Times analysis of Los Angeles Police Department data found.

More than 100 assaults, batteries and robberies were reported at the building addresses, the data showed, an average of more than seven per year at the sites. That was more than twice the rate in the years before the foundation’s ownership.

This year, journalism students at Cal State Los Angeles also reported on problems with crime within foundation buildings — as well as habitability and accessibility issues — for nonprofit news website Knock L.A.

Dyer said in a deposition from the Madison class action that any crime issues reflect broader problems in Skid Row and that he believed police were called to the building far less than surrounding properties.

Several tenants interviewed by The Times said the foundation has ignored havoc caused by violent residents, leading, at least once, to tragic consequences.

After moving into the Madison in fall 2020, Omar Deayon gained a reputation for selling drugs and intimidating others, according to internal records made available through a lawsuit against the foundation. Security footage shows Deayon, 51, brandishing a gun in a hallway. He also threatened a fellow tenant with a butcher knife in the lobby, according to an incident report. Another incident report describes Deayon tossing a chair and threatening to shoot a foundation employee. In spring 2021, property managers listed him as one of their most aggressive and violent residents, internal foundation records show.

For all this, according to the lawsuit and tenant interviews, Deayon was nicknamed “Killa.”

Throughout summer 2022, Deayon’s across-the-hall neighbor James Ellis told property managers that he couldn’t sleep because of Deayon’s loud music and guests, according to internal incident reports. Just before midnight on July 26, Ellis again asked Deayon to quiet down.

Security footage shows what happened next. A hand with a gun extended from Deayon’s door, shooting Ellis, who fell into his room. Deayon immediately entered the hallway, gun in hand, while a woman, obviously shaken, ran from his room.

Ellis, 62, survived but still can’t work. He now spends much of his days sitting in his same room, stressed.

“I ain’t got nowhere else to go,” Ellis said.

The bullet remains lodged in his back.

Deayon has pleaded not guilty to attempted murder charges and is being held in Men’s Central Jail on $1.2-million bail. In a jailhouse interview, Deayon denied shooting Ellis and cited his own mental illness and the building’s conditions for his problems while living there.

Ellis sued the foundation for negligence. Foundation attorneys say in court papers they intend to file cross-complaints against Deayon and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. They contend that they secured an eviction judgment against Deayon a month before the shooting but deputies did not lock him out because the paperwork “supposedly contained a clerical error” that was later fixed. In a subsequent filing, the foundation clarified that the “clerical error” involved an outside attorney filing Deayon’s eviction lawsuit on the wrong unit.

To be sure, other Skid Row landlords have had severe and, in some cases, worse conditions in their buildings. The neighborhood’s largest landlord, the nonprofit Skid Row Housing Trust, financially imploded earlier this year, leaving nonexistent security, smashed doors and windows, squatters and filthy bathrooms across its 29 properties. A quarter of its 2,000 units became uninhabitable, and the city pursued a receivership to take over the trust’s assets. Residents of the Cecil Hotel, a 600-unit single-room occupancy building in Skid Row owned by a for-profit developer, live with mold, vermin and regular acts of violence.

But the foundation stands out among L.A.’s homeless housing providers in the frequency of complaints, even compared with the collapsed trust.

On average, foundation buildings in Skid Row, Westlake and Hollywood each have faced nearly eight code or public health complaints or emergency responses annually, according to a Times data analysis. Similar properties operated by the trust had just over two complaints per year, while those owned by other nonprofit landlords Abode, A Community of Friends and SRO Housing Corp. all had annual rates less than two.

Some complaints include multiple potential problems. Residents have described 171 instances of safety and sanitation, plumbing, electrical, construction, heating and pest issues within 118 code complaints at the Baltimore, King Edward and Madison.

Troubles extend beyond those buildings. At the Olympic, a 172-unit complex in Westlake, code complaints have more than doubled since it was acquired last year. In September, hot water was out in the building for more than two weeks, according to the city housing department.

There’s a pending habitability lawsuit over conditions at the Sinclair, a 190-room building also in Westlake, while internal foundation records consistently show electrical failures at the Whitley, a 61-unit property in Hollywood, in 2021.

Residents told foundation staff that the Whitley was losing power 10 to 20 times daily, sometimes lasting almost the entire day. One said the building would lose power whenever he turned on his microwave.

Tenants complained that their groceries were spoiling. Dyer said in an internal email that he sympathized with the residents but nixed an employee’s suggestion to hand out supermarket gift cards as compensation. “Food can last up to 24 hours in a fridge with no power,” Dyer wrote.

Foundation officials knew the Whitley needed electricity upgrades before occupying the building, according to emails between a construction manager and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. But the manager blamed the public utility for delaying repairs.

It’s one of many times that foundation executives have pointed at others for problems. Besides the Ellis case, the foundation has filed cross-complaints in different lawsuits, including two against the Madison’s prior owner, Kameron Segal, alleging he failed to disclose the building’s true conditions. Segal could not be reached for comment.

George Handy, a 43-year-old resident of the Baltimore, said he has regular colds and stomach pains living without heat and amid roach infestations. ‘I wouldn’t even wish this on my worst enemy.’

Myers accused Annette Harings, an attorney representing foundation tenants in the Madison class action and six other cases filed since 2019, of exaggerating the building’s problems. Harings referred comment to Jennifer Kramer, her co-counsel in the class action, who said the lawsuit aims to ensure the Madison is safe and accessible.

Foundation executives also blamed the city and public utility in cross-complaints over conditions at the Madison, notably issues with its elevator.

In all six years the foundation has owned the Madison, the elevator has been out of service frequently, sometimes going offline for months at a time.

Residents, many of whom are elderly and disabled, have slept in the lobby, paid others as much as $40 a trip to carry them to their rooms or remained trapped upstairs in the five-story building, according to interviews and court declarations. A 66-year-old legally blind tenant was hospitalized in 2018 after plummeting more than a dozen feet down an open shaft when the elevator door opened without the cab present.

A 2018 video from a deposition exhibit in the Madison class-action lawsuit shows a resident, who is legally blind, fall down an open shaft when the elevator door opens without the cab present.

Weinstein acknowledged in an early 2020 interview that tenants had reason to be upset. But he said that the city and utility had “100% of the responsibility” for the elevator failures, alleging they were dragging their feet on permitting. Last December, the foundation received $100,000 in a settlement with the public agencies.

Two months later, the foundation settled the elevator lawsuit, paying 13 tenants $832,000 and additional undisclosed amounts to four others. At the time, the foundation had just agreed to more repairs, part of $600,000 Weinstein said the foundation had committed to elevator upgrades.

But the elevator is still out of service once a week for a day at a time or longer, tenants said. In August, they said the elevator was inoperable for three weeks and cordoned off with yellow caution tape only to be restored to its similar cadence of outages.

One morning in October 2019, three AIDS Healthcare Foundation activists marched into Los Angeles City Hall demanding the City Council curb evictions.

“We have enough homelessness,” one said.

That same day, a foundation attorney filed an eviction lawsuit against a Madison tenant for overdue rent.

The episode provides a stark example of the foundation fulminating against forcing people from their homes while pursuing evictions against its own residents.

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The foundation has picketed the offices of a high-profile L.A. eviction attorney and paid legal costs for hundreds of tenants at a West L.A. apartment complex fighting against a mass eviction.

“Eviction makes it hard for families to find decent housing in safe neighborhoods & has negative impacts on health, employment, education,” the foundation’s tenant activist group said on social media in 2021.

In June 2018, less than a year after buying properties in Skid Row, the foundation secured its first eviction judgment against a King Edward tenant who owed $461. From then until the pandemic began in early 2020, 51 other residents at foundation buildings lost eviction cases, according to court records.

Of those evictions, 45 were for overdue rent, court records show, including one over a $200 debt. Three of the other judgments were against resident managers who lost their homes when they lost their foundation jobs. Three others were against tenants who the foundation said had acted violently, and the remainder for a tenant who had unauthorized occupants.

The foundation has pursued far more evictions than these. California law typically shields eviction lawsuits from public view unless a landlord wins a judgment. But records made available as part of the Madison class action reveal the foundation filed 73 eviction cases against the building’s tenants between mid-2018 and early 2020 — nearly double the number of judgments from the Madison that appear on the public docket.

Lucero, the Madison tenant who was evicted in fall 2018, said she had an agreement with the prior owner to serve as a building manager in exchange for living in two adjacent units rent-free. The foundation won an eviction judgment against her for nonpayment for one of the units. Months later, it had her arrested for trespassing when she was continuing to reside in the other, after which her belongings were thrown away. Lucero sued the charity. In court filings, the foundation maintains she had sufficient time to collect her possessions and it did not discard them unlawfully. Lucero settled the case earlier this year, receiving an undisclosed amount higher than $10,000, court records show.

The foundation says it offers assistance to those who are behind on rent before filing eviction lawsuits, but ultimately needs its tenants to pay.

Edwin Linwood, a 72-year-old resident of the Madison with lung disease, struggles up the stairs when the elevator is out of service.

He says vermin are a constant presence: ‘There are roaches, bedbugs, spiders, various other critters all over the building. They seem to be inside the walls.’

“In order to make the project financially viable and build self-sufficiency, we exercise tough love on paying the rent,” Weinstein told The Times in 2020 when asked about evictions at the Madison.

Because rent revenues are so low, the foundation has had to spend $15.4 million subsidizing building operations across its portfolio, Myers said.

Myers said that most evictions “were of tenants who paid little to no rent despite having the ability to do so.”

“Tenants who pay nothing are taking away the opportunity to have stable housing from those who pay rent,” he said. “AHF’s model of housing thousands of low-income tenants is only sustainable if AHF’s extremely low rents are paid.”

Nevertheless, Shamine Robinson, who was evicted with her three children in a dispute over rent in early 2020, says her situation reveals the foundation’s hypocrisy.

“You can’t talk about how bad evictions are, but then be handing people out one,” said Robinson, who was living at Sunrise on Sunset, a 37-room converted motel in Hollywood.

Robinson said she wasn’t aware she had formally been evicted until informed by a Times reporter. She said her family had left the property voluntarily after receiving an initial notice. Robinson struggled to find a new apartment, and after learning of the eviction on her record believed that was the cause.

“Having the eviction notice,” she said, “that’s not a short-term thing, that’s long-term.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck in spring 2020, local, state and federal authorities prohibited evictions for tenants who were behind on rent for pandemic-related reasons.

Rent collection slowed, and the foundation used its retail and tenant organizing operations to recoup some of the losses.

The foundation runs a chain of thrift stores called Out of the Closet, and it set up a program for its tenants to sort and hang merchandise. Beforehand, residents agreed to forego a paycheck, and instead, every hour of work they put in would knock $15 off their rent debt, according to a copy of the contract they signed.

Much of the foundation’s tenant advocacy through the pandemic centered on its support for rental assistance. It published a full-page advertisement in The Times warning of mass evictions statewide should that money not come. And it held news conferences calling for public dollars alongside elected officials, including Los Angeles City Councilmember Kevin de León, who represents Skid Row and whom the foundation previously employed as a housing consultant.

Ultimately, the foundation received more than $1.5 million from pandemic rental debt programs through February, a property manager said in a court hearing that month.

While landlords weren’t allowed to evict for overdue rent accrued during the pandemic, they could sue tenants in small claims court.

The foundation has filed 69 such cases since last December, court records show. Among those targeted for back rent was Ellis, the Madison tenant who was shot and separately sued the foundation over the incident.

While Ellis’ lawsuit remains pending, the foundation won a small claims judgment against him in July for $2,490.

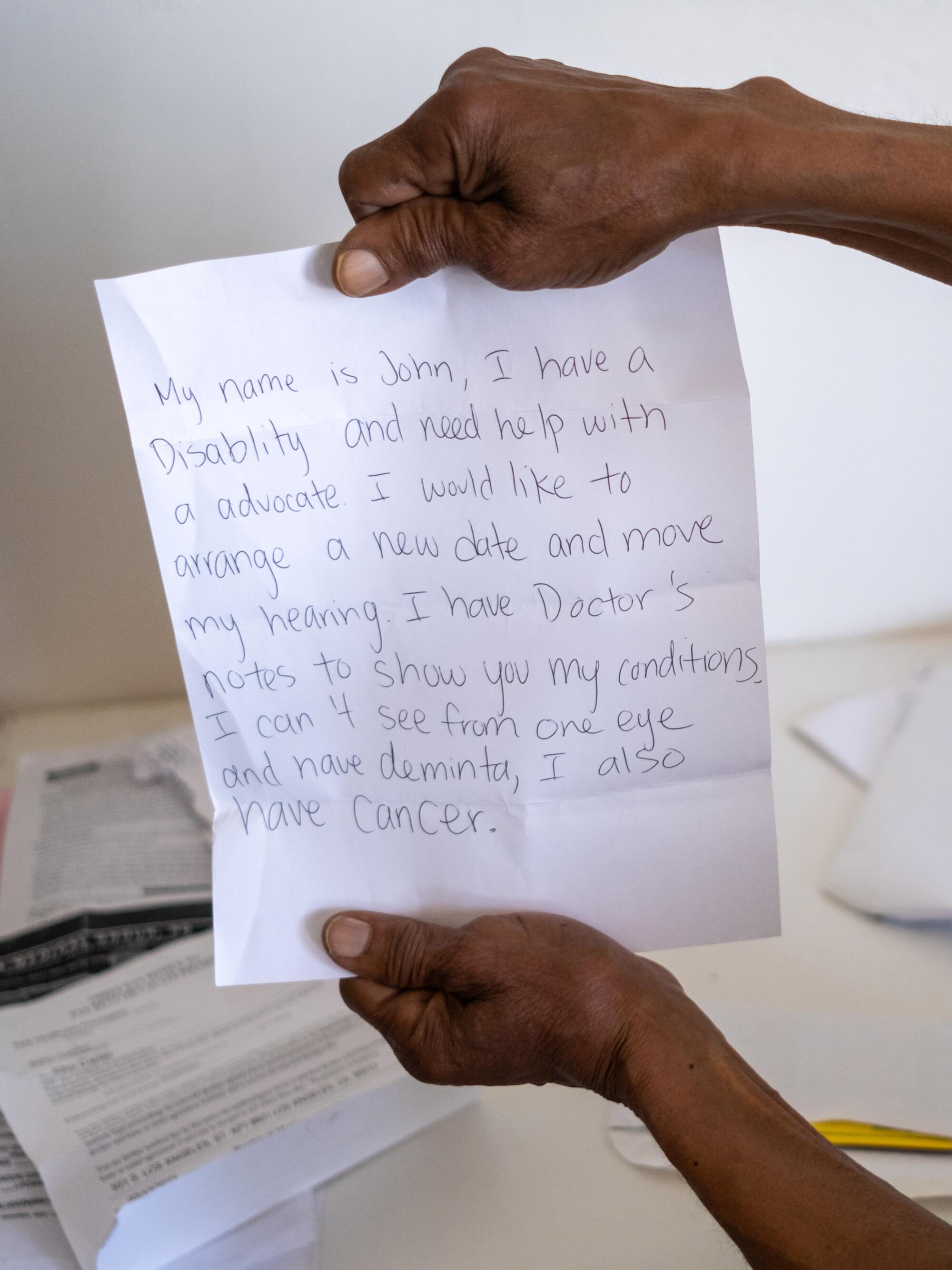

Living on the sixth floor of the Baltimore, John Carter, 72, says he suffers from memory loss, dementia, depression, bipolar disorder and mania. He’s addicted to crack cocaine. He’s incontinent and blind in one eye. Arthritis afflicts his knees and ankles.

Even when the hot water is working, Carter said, it leaves a milky residue, and he struggles up the stairs when the elevator is out. Because of the conditions in the Baltimore, Carter said he doesn’t believe he should have to pay rent. But if he must, he’s told the foundation it can take money directly from his Social Security check.

“I told them to put me into money management,” Carter said. “I told them I was into drugs. It’s not that I’m trying to deceive anyone.”

Instead, last December the foundation served him with a small claims lawsuit.

In February, Carter ventured to a downtown courthouse in an electric wheelchair and explained his predicament to a judge. The judge said it was obvious Carter was indigent and infirm, but ultimately ordered him to pay $8,873 in back rent. She also told the foundation property manager that its social workers should schedule a doctor’s appointment for a hernia Carter complained about during the hearing.

The foundation didn’t help Carter find a doctor, he said. It doesn’t employ social workers or offer social services for its tenants, including those, like Carter, with mental health and addiction problems.

Not providing these services, the foundation has said, was a financial choice that allows the charity to purchase more properties than it otherwise could. This strategy, it argues, best responds to the need for housing in Skid Row and other neighborhoods with high rates of homelessness.

“Costs would spiral out of control if AHF also provided services, such as mental health services,” the foundation wrote in an unsigned defense of its approach in 2022 published on its website.

In general, this leaves foundation tenants responsible for finding their own supportive services.

The foundation calls what it does “housing first,” referring to efforts that give homeless residents a permanent home without requiring sobriety or other preconditions. Myers said housing first “is a tried-and-true housing policy that has been successful across the country and around the world.”

But the foundation isn’t practicing “housing first” under federal and state guidelines, because the definition includes access to services.

Decades of research show that housing-first programs pairing permanent housing with robust social services keep chronically homeless residents with serious mental health and drug problems housed. Models that serve the same population without services tend to fail, said Margot Kushel, a doctor and professor of medicine at UC San Francisco and director of the school’s Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative.

“Plenty of folks who’ve been homeless a long time just need an apartment,” said Kushel, who published a study on California’s homeless population this year. “But when you’re putting people who have severe mental health and substance-use disorders into apartments, somebody needs to provide these services.”

Without them, buildings could devolve into disorder with high rates of eviction, property damage and death, she said.

Over the last six years, 20 people have died at the Madison, including three over three days last fall, according to coroner records. The records show 50 deaths in all foundation buildings, nearly half listing drug toxicity as the primary cause, with an additional third caused by heart-related illness.

The lack of services has degraded quality of life for those without mental health or drug problems as well.

“The people who have themselves together in these buildings feel like baby-sitters,” said Mariah Darling, 37, who lived for six months in 2021 in the Pride Hotel in East L.A.

The strain of helping distressed tenants and calling 911 on those who were violent or acting out took its toll, she said. Another resident, she said, groped her and exposed himself while she showered in a communal bathroom. Darling eventually left and moved back in with family.

The foundation has leased two of its smaller properties, one in Van Nuys and one in East L.A., to nonprofits that provide interim housing with social services. Last year, the foundation attempted to lease an additional 235 units in four other buildings to tenants who had case managers through a program arranged by People Assisting the Homeless, or PATH, one of the region’s largest service providers. Over the summer, however, PATH terminated the contract and the foundation has since sued PATH, claiming a breach. PATH officials declined to comment, citing the litigation.

The foundation also employs workers to connect tenants with outside services. But when those workers pushed to provide residents with more assistance two years ago, executives rebuffed their attempts.

‘The people who have themselves together in these buildings feel like baby-sitters.’

— Mariah Darling, who lived in the Pride Hotel for part of 2021

Coy, the former employee, started in late 2020 as part of a three-person team that helped residents secure identification cards, apply for government benefits and find therapists and drug rehab programs.

Sometimes, she faced emergencies. Once, in spring 2021, Coy said, she intervened in a tenant’s attempt to strangle himself, her fingers turning purple as she prevented him from tightening an extension cord around his neck. Over the next two weeks, Coy said, she and her boss, Karla Leiva, cared for the tenant’s dog in their homes until he returned from the hospital.

“I’m not going to put his dog in a shelter when he just tried to commit suicide,” Coy said.

By the time of that incident, Leiva had been arguing for months that arranging more services for residents was the only humane way to address the suffering within the foundation’s buildings, according to records from subsequent litigation between Leiva and the foundation.

“If we do not want to go this route then we need to rethink who we want to serve because we are setting people up to fail,” she wrote in a June 2021 email to Weinstein and other foundation executives.

But foundation leaders said they believed Leiva’s attempts to offer greater care were too time-consuming and distracting to property managers and security guards, none of whom were trained to handle tenants’ social service needs, according to a court declaration from Liliana Zoldi, the foundation’s director of human resources.

“Those efforts took a lot of time, sometimes hours per day for just one tenant,” Zoldi said. “The efforts mostly failed, in my opinion.”

Also that June, according to Coy and internal emails, the foundation’s top property manager instructed her to pull back on connecting tenants with healthcare. Instead, he wanted her to focus on the foundation’s bottom line: getting residents to apply for rental assistance or work off their debts at its thrift stores.

Soon after, the foundation fired Leiva and put the top property manager in charge of Coy and her colleague. Coy quit, convinced that Weinstein and other executives were ignoring residents’ needs

“They envisioned this idea of just handing someone a pamphlet and telling them to go off and go access the resource,” Coy said. “That’s really not possible. It just showed a lack of awareness of what tenants were dealing with.”

In the summer, with pandemic protections expiring, the foundation again began evicting residents who were behind on rent. The first successful case, court records show, was against a Baltimore tenant who owed more than $17,000.

Vance Pitts, a 76-year-old resident of the Madison, suffers from poor circulation and swelling in his legs. He said he’s paid other tenants to carry his groceries when the building’s elevator is broken.

‘I’m afraid I’m getting to the point where, boy, if my legs give out that’s it,’ Pitts said.

But the resident, who has been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, didn’t know he was being evicted, according to court documents filed by the tenant’s mother. She said she found the paperwork months after it had been filed while cleaning his room.

In September, the mother pleaded for mercy, telling a judge her son would be forced to the streets. She said his mental health would worsen and offered to begin making payments on his debt. But the judge said she wasn’t party to the case and declined her request.

During the hearing, a foundation attorney emphasized that the charity did not provide residents with mental health services, adding that the tenant owed too much to let him remain housed.

“Perhaps the defendant needs to find a better place,” the attorney said.

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.