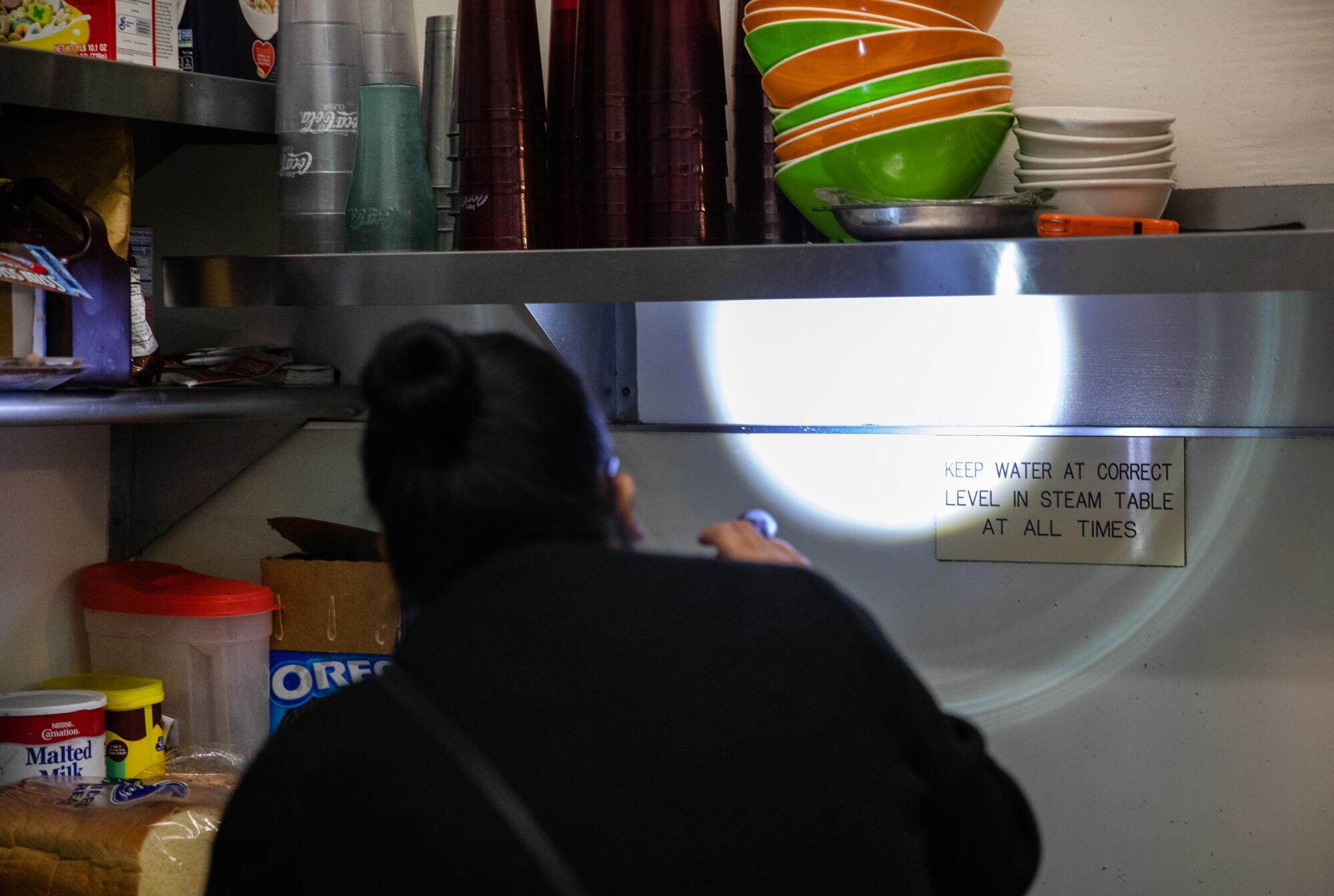

Ngoc McShane moved swiftly, armed with a flashlight, thermometer and pen. She crawled through dark storage areas, aiming her light into corners and peeked into cupboards and stoves.

She resembled a detective looking for clues. But instead of fingerprints she was on the trail for signs of unsanitary conditions: food debris, vermin droppings, rogue employee coffee cups.

McShane is a public health inspector for the Los Angeles County Department of Health, one of 159 environmental health specialists tasked with protecting the public from food-borne illnesses.

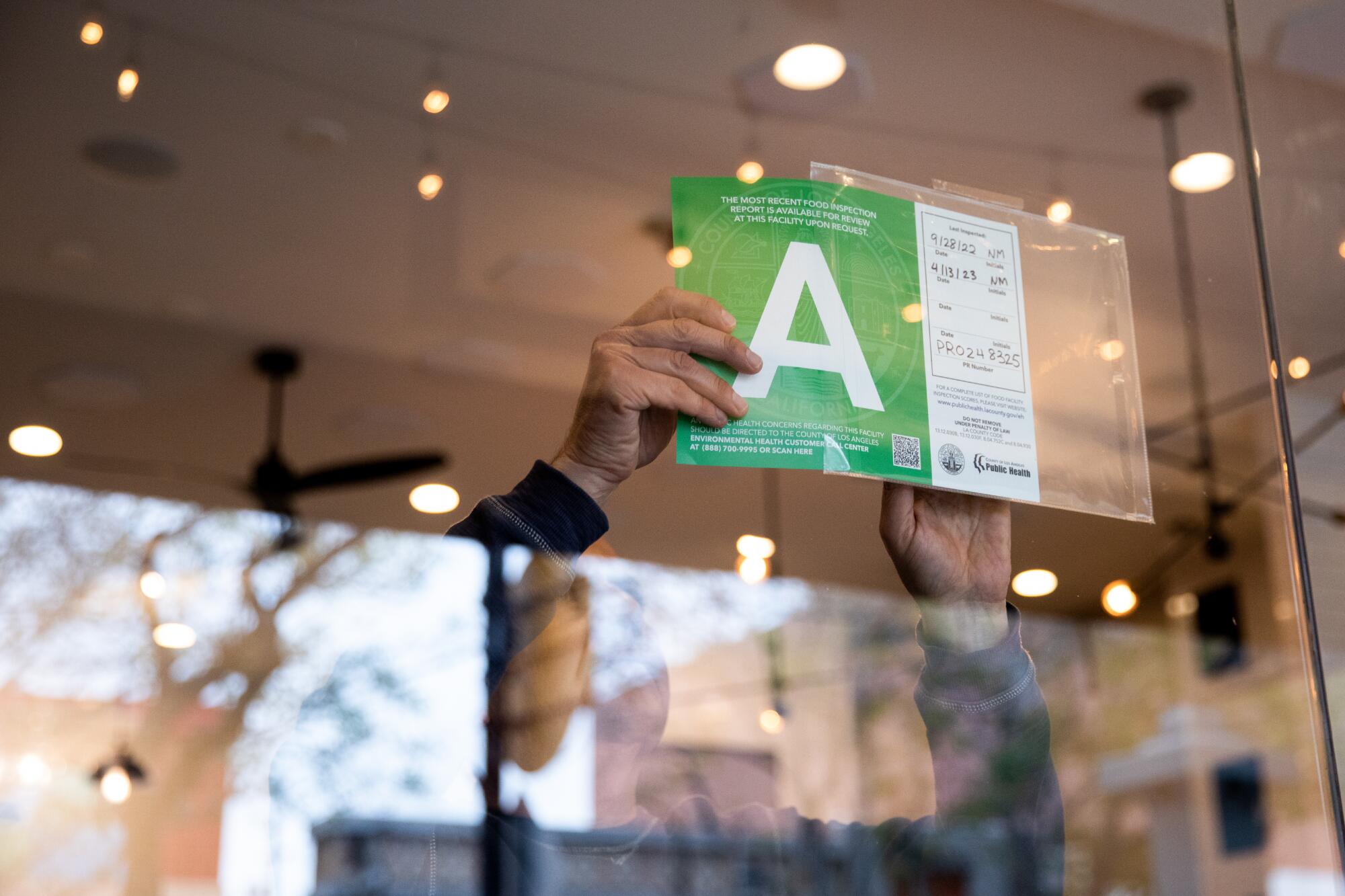

Her mere presence sometimes sparks fear and commotion in a kitchen, sending workers scrambling to pick up a dustpan and broom to sweep up debris. She shows up at food establishments unannounced, documents any violations she observes and then assigns letter grades that must be displayed on the front windows of the businesses.

If the violations are too numerous, McShane has the power to shut down a restaurant immediately.

L.A. health inspectors are represented by the Teamsters Local 991. Nearly every day, the specialists posted at 29 offices — north from Lancaster, south to the Long Beach city limits and east to Claremont — fan out across Los Angeles County. And nearly every day, the inspectors shut down a few food-serving establishments, from restaurants and bars to fast food joints and convenience stores.

Most places pass inspection and simply receive a letter grade.

The public can follow the inspectors’ work on L.A. County’s Public Health website, and from 1989 until 2004, this newspaper published a listing of restaurant closures.

In January 1998, Los Angeles County began assigning public letter grades to restaurants and other businesses that sell food, after KCBS reporter Joel Grover (now with KNBC) and the station’s investigative team used hidden camera footage to show vermin and food-handling violations in popular Los Angeles restaurants.

Letter grades have been posted at restaurants in San Diego County since 1947. After Los Angeles launched its letter grade program, municipalities and counties throughout the country implemented similar systems.

The L.A. city attorney is looking into a hospitality group that runs some of the trendiest restaurants in Hollywood over healthcare service fees tacked on to diners’ bills.

Initially, some argued that the letter grade system unfairly penalized certain restaurants without taking into account traditional food practices. Jonathan Gold, at the time a Pulitzer Prize-winning restaurant critic for LA Weekly, argued against the letter grades, stating that it would hurt operators making food using age-old methods without refrigeration, such as salami or Peking duck.

Years later, Gold, who later became restaurant critic for the Los Angeles Times until his death five years ago, told the Wall Street Journal he’d changed his stance. “I’ve had some splendid meals at restaurants with Cs,” he said, but conceded that “his gastronomical well-being [had] been enhanced by the system.”

McShane looks like most moms in Los Angeles. Hair tied back, she wore black slacks and comfy flats. A car seat was positioned in the back of her Prius. She parked, grabbed her laptop bag from the trunk and slung it over her shoulder. She wore a mask at all times.

McShane’s unassuming appearance belies the power she wields in a culinary city like Los Angeles, where diners at some places tend to revere chefs as demigods. In the last decade, as the dining scene has exploded in Southern California, the work of a health inspector is arguably even more consequential.

At the same time, the department is operating short-staffed — down 81 health inspectors. The vacancy count is the highest it has been in the last five years. This can affect the number of routine restaurant inspections being performed. Agency officials blame a combination of retirements and lack of qualified applicants as some of the reasons for their dwindled ranks, a spokesperson said.

At one point, inspections of high-risk establishments — that is, full-service restaurants — were happening at least once a year due to the pandemic and staffing shortages, the spokesperson said. Currently, the agency is in the process of returning to their pre-pandemic goal of inspecting high-risk restaurants three times a year.

Agency officials insist that the public is still safe regardless of inspector vacancies. To make up for the shortage, agency officials said, they are using overtime and temporarily reassigning inspectors to different areas of L.A. County to make sure each office has minimum staffing levels.

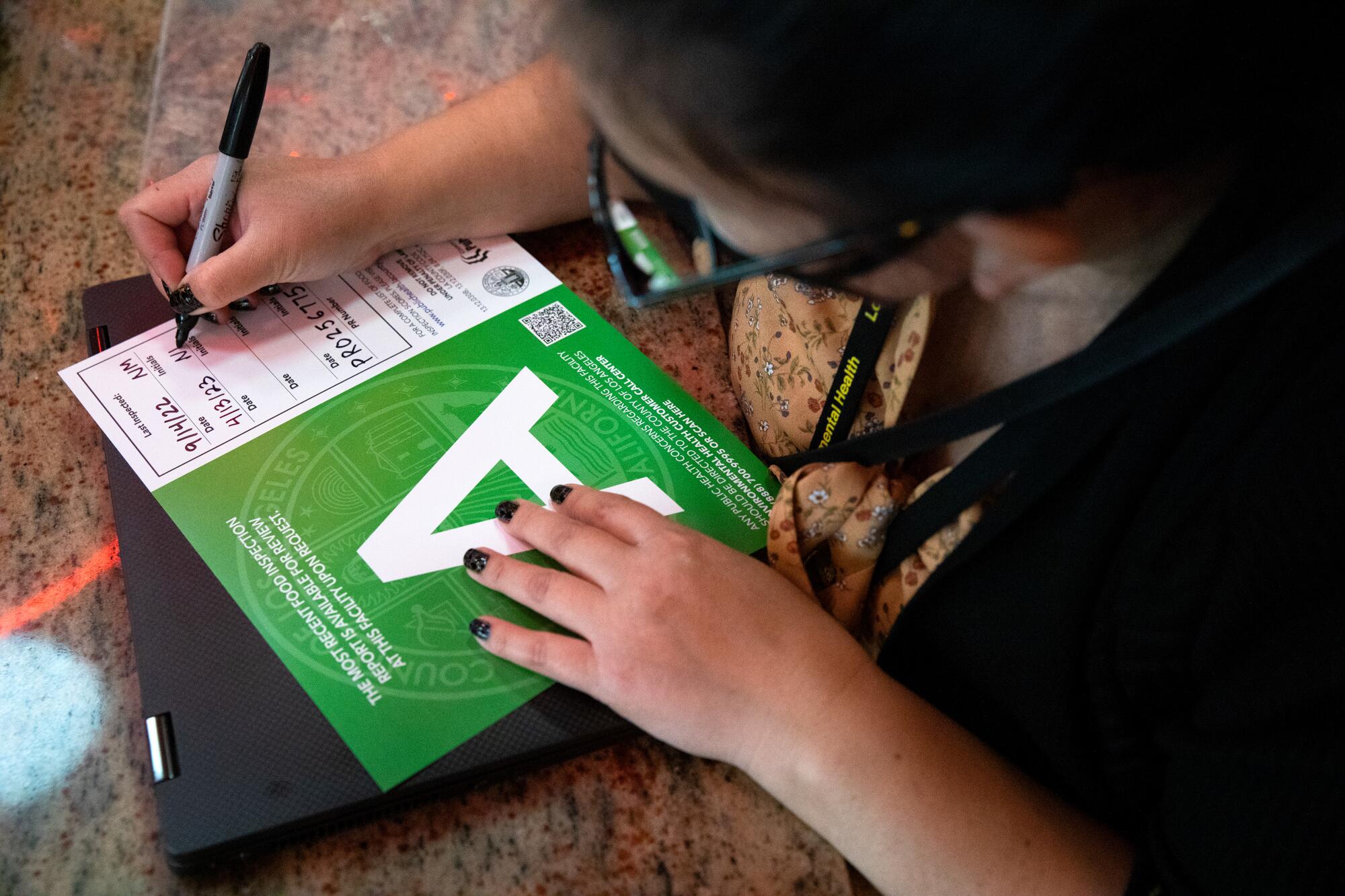

How inspectors arrive at the letter grades can be a bit complex. Scores are determined by three types of violations: major, minor and good retail practices.

Major violations mean a deduction of four or 11 points. For instance, food not kept at the right temperature costs four points. A minor violation, such as old food debris on a meat slicer costs two points. Good retail practices violations, such as a missing lightbulb or an employee’s coffee cup near a food station cost restaurants one point each.

First stop in Burbank

On a recent spring morning, McShane walked into the Great Grill, a 1950s-inspired diner on San Fernando Boulevard in Burbank. The aroma of hash browns and bacon welcomed patrons into the restaurant decked out with checkered floors and kitschy post World War II memorabilia.

McShane introduced herself to Victor Safar, who’d just served platters of eggs and toast to a couple seated at a booth upholstered in red vinyl. She flashed her badge and asked Safar for the person in charge.

George Martin, a jovial 60-year-old chef who has worked in this kitchen for more than a decade, walked in from the back.

“I’m Ngoc from the health department,” McShane told him.

He’d remembered her from previous inspections and greeted her with a smile. He escorted her into the cozy kitchen. Like most restaurant workers, Martin knew the drill. He let McShane do her thing.

Los Angeles and Orange County restaurants are struggling to find staff, resulting in shortened hours, smaller menus, longer wait times, angry customers.

Probe in hand, she stuck food containers with a thermometer. She made sure the cold items were cold enough — at least 41 degrees Fahrenheit or below — and the hot stuff, hot enough — at least 135 Fahrenheit or above.

“All our temperatures are good so far,” she told Martin.

He nodded and tried to stay out of McShane’s way. He sprinkled cheddar cheese and bacon bits on a salad for one of his regulars. The family-operated restaurant serves breakfast all day: waffles, pancakes, eggs, omelets. The diner wasn’t all that full and food prices were soaring, a fact Martin lamented.

McShane entered the walk-in refrigerator where she found a container of raw steak stored directly on an opened package of hot dogs, a minor violation of the California Health and Safety Code, which requires food to be separated and protected.

There wasn’t any cross-contamination, but it cost the the Great Grill a point.

A little more than halfway through the inspection, restaurant owner Sam Yerkanyan showed up. McShane greeted him before inspecting the restaurant’s bathroom. Yerkanyan, who has operated the diner for more than 20 years, said the inspections normally don’t worry him.

He has bigger concerns, he said. He worried about breaking even, especially after taking such a big hit during the restaurant closures that followed COVID-19. Customers — a good portion of them elderly diners — weren’t coming in like they used to.

Before the start of the pandemic, the average Los Angeles resident spent more than 50% on food away from home, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported. From 2020 to 2021, that percentage declined to 36.5%, according to the most recent data available.

McShane’s inspection took about half an hour. At the end of it, she typed up her report and sat down with Yerkanyan to explain why his restaurant scored an A, though it scored 91 points, lower than in previous inspections.

There wasn’t enough separation or a splash-guard between the hand-washing and dish-washing sinks, she told him. And one of the workers didn’t know what the required chlorine concentration was supposed to be in a sanitation bucket. She knocked down four points for those two critical violations. The other five violations — stuff like the accumulation of grease on the hood and hood filters of a stove — were minor.

Yerkanyan nodded his head, promising to fix the issues, before he posted the “A” grade on the diner’s front window.

“It’s fair,” he said about McShane’s assessment.

When to shut down

A health inspector will immediately close a restaurant if there is no water, a sewage backup or a vermin infestation. Vermin closures result in a minimum 48-hour permit suspension. Operators who fail to fix violations can have their permit revoked or suspended.

Restaurant operators are usually pretty understanding, McShane said. She’s only had one instance when a restaurant operator didn’t let her into the kitchen, she said. In that case, the restaurant patrons persuaded the worker to eventually let her in.

Usually, workers are cordial and spirit her away to the kitchen so she can begin her inspection. Sometimes, McShane said, workers get nervous. They talk really fast and stumble over their words. In those situations, she tries to put them at ease by exchanging pleasantries or pointing out what they’ve done right.

She knows that these restaurant managers and owners may perceive her inspection as the ultimate test. Anything lower than an A can be akin to a scarlet letter for a restaurant.

McShane knows because she’s been on the other side. Nearly eight years ago, she worked as a pastry chef in a bakery in Atwater Village. One day a health inspector arrived at the bakery.

“I remember being kind of nervous,” she recalled.

Eventually, that went away and she struck up a conversation with the inspector. Could this be a career change for her? The bakery was going to close and McShane was growing tired of her job. Baking had always been her passion but making it her job had taken all the joy out of it, she said.

The inspector convinced her to join the health department.

Perfect scores

McShane’s past experience helps inform how she approaches restaurant workers, she said.

”I like to let the operator know that I’m not here to mark down violations,” she said. “My job is to educate and monitor. There is enforcement, if it calls for it.”

Health inspectors try to visit full-service restaurants at least three times a year. Fast-food establishments get visits twice a year and retail stores selling prepackaged food get a yearly visit.

Whenever the health department gets word of a water shutoff — either intentional or accidental — in their jurisdiction, they dispatch inspectors to the affected area to make sure all food-serving establishments have closed. Most voluntarily shutter until the water is back on. But, officials said, there are always a few restaurants that venture to stay open during a water shut-off.

That’s a big no-no, food safety-wise. Health inspectors make sure to shut them down.

“If you have no water, how do you clean your hands after you go to the bathroom?” said Mabel Cedeno-Gale, an Environmental Health Services manager at the Los Angeles Department of Public Health. “How do you sanitize a cutting board ... a knife?”

The restaurant says the 18% service fee attached to checks is part of a vision to make pay more equitable among all workers. The suit filed Tuesday in L.A. seeks damages for what servers claim are tips.

One of the most common health inspection violations are for improper cleaning of equipment, such as food prep areas, Cedeno-Gale said. After the Great Grill, McShane went on to inspect three more restaurants in the same area. All restaurants she visited scored an A.

About a block away at Wild Carvery, McShane chatted it up with Vahe Aiwazian, owner of a fast-casual joint that serves organic sandwiches, burgers and salads. The kitchen looked new and nearly spotless.

At one point, McShane popped out her thermometer and poked it into various cold and hot food containers.

“Your temperatures are beautiful,” McShane told him. Aiwazian lit up with glee.

A year ago, he was one point shy from scoring a perfect 100. On this occasion, the restaurant scored 97 points after a few minor violations. Grease and food debris had accumulated on the floor underneath the fryer, the fryer cabinets weren’t clean and had accumulated grease, and the ware-washing machine wasn’t dispensing enough sanitizing solution.

When asked whether he was happy with the score, Aiwazian shook his head.

“No,” he said.

“He wants 100,” McShane quipped.

“99 I could live with,” he said, laughing.

“I don’t do it for the health department standards. I base it on my standards. It has to be done perfectly,” he said. “It’s good that she comes.”

By 3:27 p.m., McShane was done walking. She drove back to the office to write up her reports, which would later be added to a database of inspection reports the public can easily peruse.

Whenever McShane is out with her two children and they walk past a restaurant she’s inspected, she’ll point it out. “Mom looks for cockroaches all day,” McShane’s 7-year-old daughter likes to tell people.

“That’s not the only thing I do in my job,” the mom reminds her daughter.

An inside look at how LAUSD develops and prepares new menu items — and what the kids really think about them.

McShane says she’s thankful for her career switch. She enjoys baking again. She’ll bake for her family and regularly brings her carrot cake and brownies into the office. When she doesn’t bake or cook at home, she’ll take her family to their favorite restaurant: an Ikea near their home.

The furniture store with Swedish-inspired sofas and a menu of Swedish meatballs, macaroni and cheese and chicken wraps checks off all the right boxes. It’s a reasonably priced hot meal for her family. Her kids approve — especially of the fries.

And she’s personally inspected it. It scored an A.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.