The 10,000-year history of our favorite Super Bowl dip

Humans have been eating avocados on this continent for some 10,000 years or possibly longer, according to the archeological record. And we’ve been doing it more or less the same way the whole time, by mashing the tree’s fruit into a pulpy paste known as guacamole.

It’s that green, chunky mass, unusual for a fruit: somewhat savory, buttery in texture and high in monounsaturated fats. On occasion, you might find slices draped over a tostada or enchilada or omelet, but when mashed, it’s all “guac.” That includes iterations like being spread on artisanal toast with seeds and wispy greens (still weird but OK), lathered into the build of a turkey burger with Swiss cheese or served alongside chips and other salsas at watch parties for all-American sporting events like the Super Bowl.

The history of the annual NFL championship game as a cultural event is firmly entwined with the rise of guacamole in mainstream U.S. culture, according to Times columnist Gustavo Arellano, whose encyclopedic knowledge on all things American Mexican food is evident in his 2012 book, “Taco U.S.A.”

“Guacamole doesn’t take off until chips take off, and chips don’t take off until Doritos take off, and that’s the late 1960s,” Arellano says. “Guess what’s starting to blow up at that time as well? The Super Bowl.”

The Hass Avocado Board, which represents growers of the best-known variety in the country, says U.S. consumers ate more than 2.8 billion pounds of Hass avocados in 2021, and consumption has been on the upswing for the past two decades.

Vickie Fite, a spokesperson for the board, said we’ll probably eat about 124 million pounds of Hass avocados this week during Super Bowl LVI festivities. It’s hard to imagine another time during the year in which avocados are consumed in such an intensely concentrated fashion by so many people (coming in close second probably would be Cinco de Mayo, when tacky bar specials promote guac and margaritas).

Now that we’ve reached what we might call peak avocado, it’s remarkable how far the fruit has truly come.

Deep roots

Guacamole is an old word, with roots in the Nahuatl word ahuacamolli, a mashup of the word for the fruit ahuacatl (associated with the Nahuatl word for “testicle,” due to the fruit’s shape and texture) and molli. In modern Spanish, avocado is aguacate.

The colonizing Spaniards didn’t care much for it when they first reached these shores, focusing instead on taking back to Europe such wondrous new items in Mesoamerica as tomatoes, chocolate and vanilla. The colonizers worried, Arellano writes, that the ahuacatl made Indigenous Mesoamericans prone to “lust.”

Native Mexicans never stopped eating them, of course, and avocados remain a star in the firmament of Mexican foods, said Carol Hernández, an associate researcher in the Bioethics Program at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). “It’s a part of the Mexican diet in an ancestral form.”

Even so, the fruit never could have reached its current status without its arrival and flourishing in California, Hernández added.

It wasn’t until around the turn of the last century that people started planting avocado trees in California, where the rich soil of our state fostered the Mexican transplant. Interest in the fruit began churning upward following the accidental creation of the Hass variety. The “mother tree” was planted by Rudolph Hass in La Habra Heights in 1926, and patented in 1935.

That original Hass, which died in 2002, spawned millions upon millions of trees, and groves soon were blanketing Southern California, largely in areas that would later be parceled out for homes. A California industry was taking shape, and as early as 1937, the New Yorker declared the avocado to be the “future of eating.”

In the postwar era, as interest in Mexican or “Spanish” foods began to grow, prepared guacamole — made with varying recipes involving (more or less) avocado, chile, onions, tomato, cilantro and lime — began surfacing in restaurants.

The guacamole at historic El Cholo is a low-wattage L.A. perennial favorite. But it’s El Torito, founded in 1954 when Larry Cano took a tiki bar in Encino and turned it into a “festive” American-Mexican restaurant, that claims to be the first establishment to popularize the practice of preparing guacamole tableside. (In his book, Arellano notes: “The history of Mexican food is peppered with such fantastic, impossible-to-prove claims regarding the genesis of any number of foodstuffs.”)

Kraft, which is not alone in putting little avocado in its product, is accused of duping consumers.

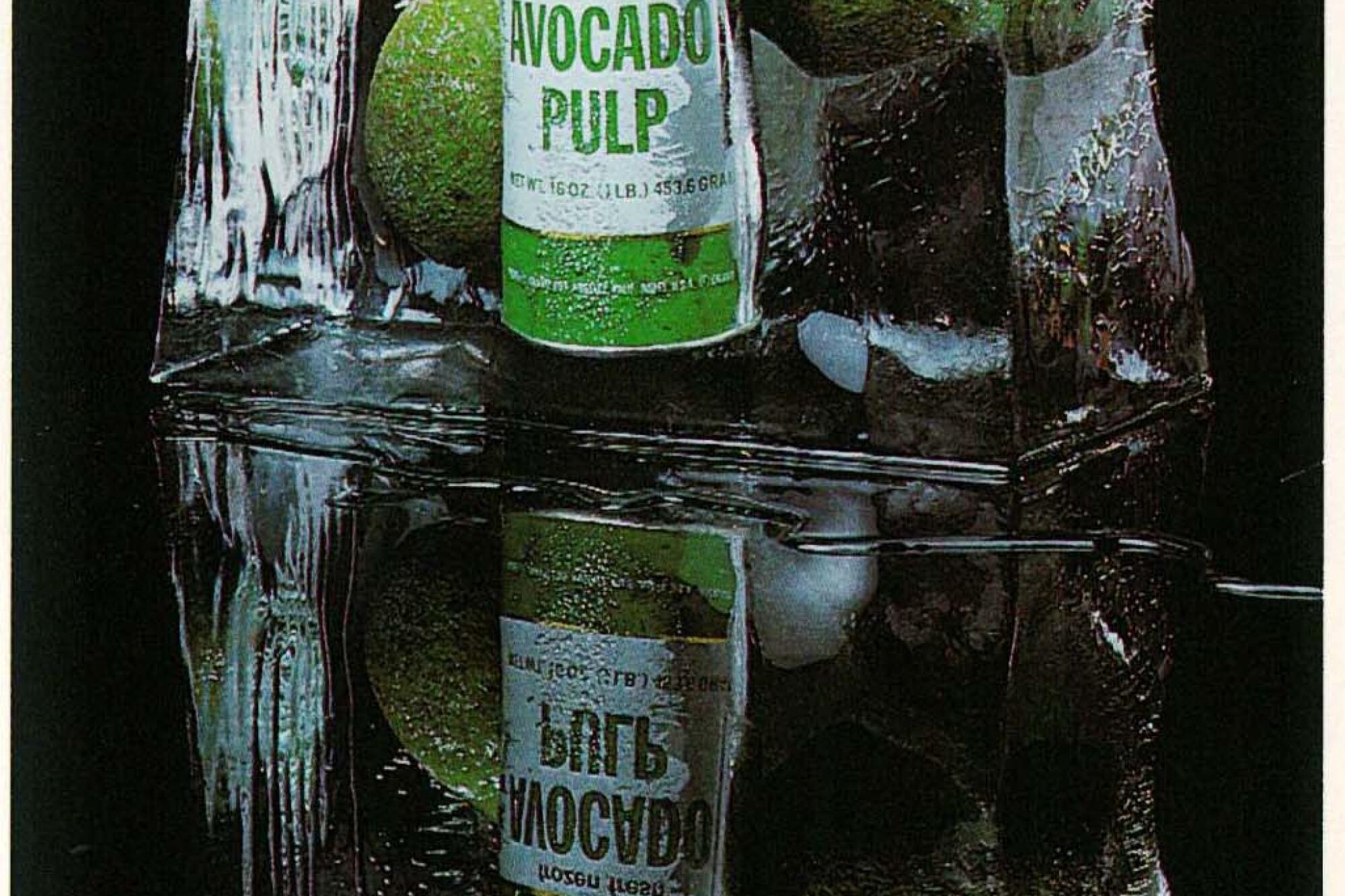

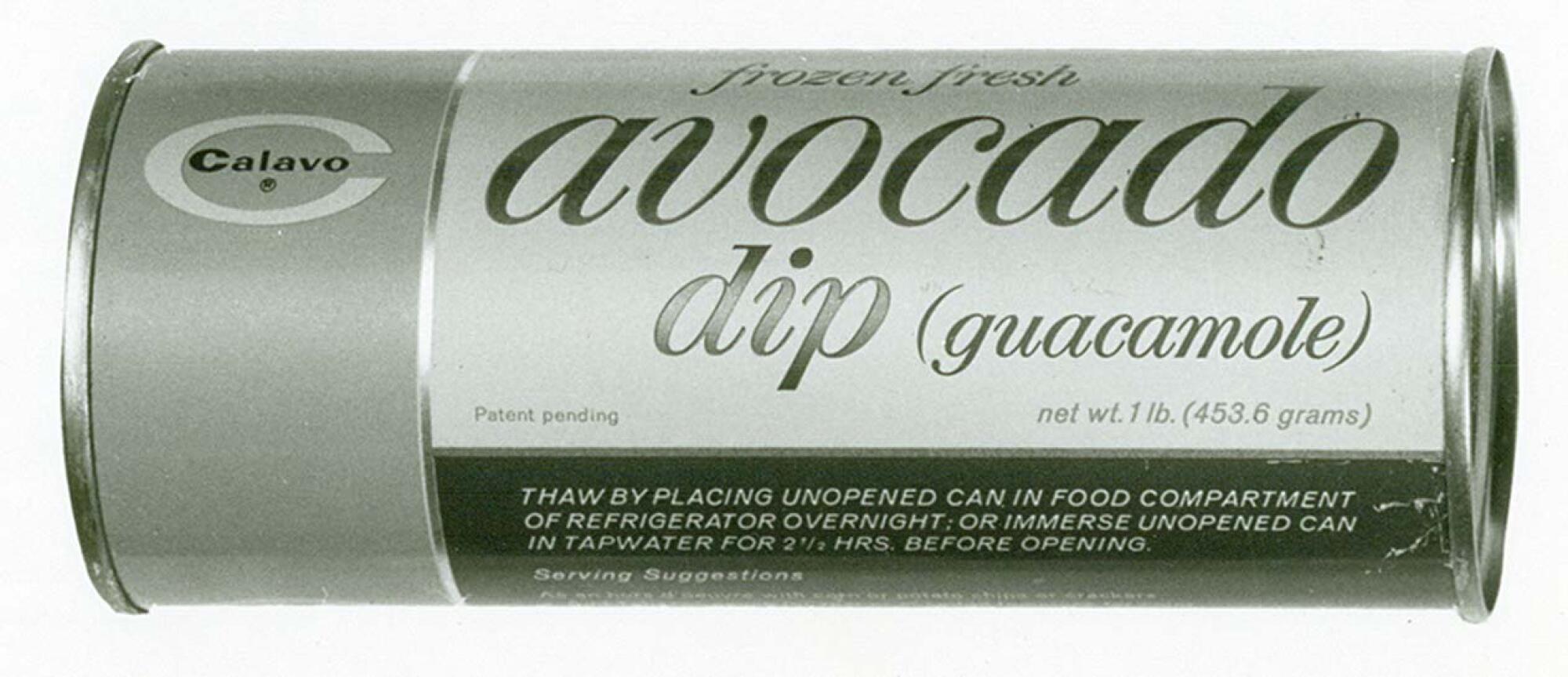

At the same time, California growers sought ways to expand their market and make avocados more accessible to new consumers in other parts of the country. In the mid-1960s, California company Calavo Growers introduced what it called the first processed consumer avocado product to be sold in stores.

It was basically one pound of frozen avocado pulp pressed into a cylinder can, the kind still used to sell frozen juice concentrate.

“You’d push it out of the container and mix it with your recipes,” said Ron Araiza, an executive vice president of Calavo. “We started producing that in 1964, and we were the first to do that.”

Over time, the health-food craze of the 1980s placed avocados in the cultural landscape as a kind of California avatar — think of the “California roll” in sushi. And, as it turns out, researchers are finding that avocados are actually healthy (monounsaturated fats are “good” fats). UCLA is currently involved in a study in which subjects eat one avocado a day for six months to test the hypothesis that avocados could help people lose weight. This trial is building on previous studies that have involved Zhaoping Li, a UCLA professor of medicine.

“We were trying to answer a fundamental question and that is, ‘Are all fats the same? Are all calories the same?’” Li said.

“It is definitely showing that calories [are] not representative of everything. Managing obesity thinking ‘calorie in and calorie out’ is very limited. We have to look at dietary quality,” Li said. Her prior research suggests avocados are beneficial in fighting heart disease and are good for the skin, among other health benefits.

“For the Super Bowl, have avocado as a natural food,” she said. “Give your body excitement with watching the game and excitement with natural foods.”

The move north

People move with foods, broadly speaking. The influx of immigrants from Mexico in a string of northward surges beginning in the late 1970s forever altered major cities in the Southwest. As people moved north, Mexico wanted to send avocados as well, but rules protected California’s produce from Mexican competition — until one key year that might be called guacamole’s inflection point.

In 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement was signed among Canada, Mexico and the United States. This new trade pact had a host of head-spinning impacts on agriculture and food, opening up Mexico to U.S. corn and, crucially, the U.S. to Mexican-grown avocados.

Mexican growers eagerly answered the demand from U.S. kitchens for Hass avocados. Production shifted south of the border, with the California-created avocado variety, and the rest became history.

Today, Michoacán, a diverse and verdant western region, is the state at the center of avocado production in Mexico and the world, and that happened almost entirely in response to U.S. demand.

But that growth has come at a cost. Avocados are becoming one of Mexico’s chief agricultural exports, but the industry is being blamed for a host of societal and ecological ills, primarily because armed and violent drug cartels have staked a claim in it. The industry in Mexico is tied to rampant deforestation in Michoacán.

In the township of Cherán, which formed an autonomous Indigenous government in response to exasperation with local-level corruption, a local leader recently told the Associated Press that commercial avocado farming only brings “violence, bloodshed.”

It’s not just drugs. Mexico’s cartels are fighting over avocados.

Araiza, the Calavo executive, said his industry is aware of the security and deforestation concerns that come with the avocado business in Mexico. He adds that Calavo — which, like most California-based companies, sources most of its avocados from Mexico — works with local governments to ensure worker safety and practice sustainable agriculture among its suppliers in Michoacán.

Despite this “sad reality,” Arellano said, most people won’t put much thought into how Mexican drug cartels are inextricably linked to the avocado trade in Michoacán. “The reason why there’s so much production of avocados in Mexico is because Americans eat it, and wherever there’s money, bad actors are going to be going in, and try to get that money,” he said.

A California staple

This year, the California Avocado Commission forecasts a 306-million-pound crop, or a 15% increase over fiscal year 2021.

“California avocado growers welcomed rains in December and January because they moved the region from severe drought to moderate drought conditions, and rain usually has a positive impact on tree health and avocado sizing,” Jan DeLyser, vice president for marketing at the California Avocado Commission, said in a statement.

The state, of course, will never again see the kind of large-scale commercial avocado growing that defined the landscape for much of the last century. California’s output now is dwarfed by growers in Mexico.

Nonetheless, generations of Californians, including this writer, have grown up with avocado trees in their backyards at one point or another, and that means the base ingredient of your favorite Super Bowl dip is forever linked to our food culture.

“In California, the only places where they really grow aguacates these days is Fallbrook and Carpinteria, and those fields get smaller and smaller,” Arellano says. “Frankly we need to start growing more of our own food here. Avocados grow humungous. They don’t need as much water as people make them out to be, and they are hardy, magnificent trees.”

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.