Ian James is a reporter who focuses on water in California and the West. Before joining the Los Angeles Times in 2021, he was an environment reporter at the Arizona Republic and the Desert Sun. He previously worked for the Associated Press as a correspondent in the Caribbean and as bureau chief in Venezuela. He is originally from California.

1

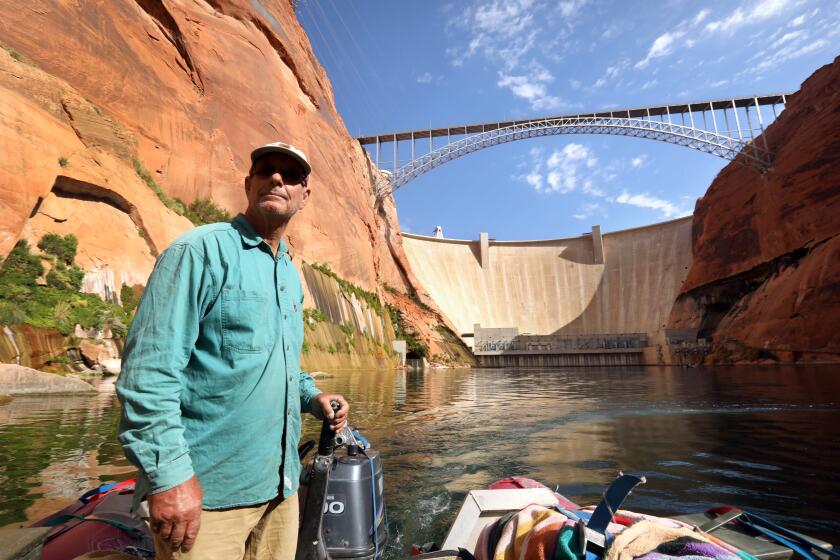

Federal officials have discovered damage inside Glen Canyon Dam that could force limits on how much Colorado River water is released at low reservoir levels, raising risks the Southwest could face shortages that were previously unforeseen.

The damage was recently detected in four 8-foot-wide steel tubes — called the river outlet works — that allow water to pass through the dam in northern Arizona when Lake Powell reaches low levels. Dam managers spotted deterioration in the tubes after conducting an exercise last year that sent large flows from the dam into the Grand Canyon.

To reduce risks of additional damage, federal Bureau of Reclamation officials have determined that flows should be reduced in the event of low reservoir levels. The infrastructure problems in one of the country’s largest dams have created new complications as water managers representing seven Western states negotiate long-term plans for reducing water use to address the river’s chronic supply-demand gap and adapt to the effects of climate change.

“Because of the dam’s design, there are real structural risks under low elevations that could potentially leave stranded as much water in Lake Powell as California’s largest reservoir, Lake Shasta,” said JB Hamby, California’s Colorado River commissioner.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

Such a scenario could lead to significant unexpected cuts in water deliveries to California, Nevada, Arizona and Mexico.

“There are a couple of ways to deal with this, absent an infrastructure fix,” Hamby said in an email. “One, reduce releases to Arizona, California, Nevada, and Mexico.”

But he said that could be a violation of the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which guarantees that the states in the river’s lower basin receive a certain quantity of water.

A second option, Hamby said, would affect the four states in the river’s upper basin: Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico. He said that could include reducing water use in the upper basin states or releasing water from upstream reservoirs.

“An engineering solution is preferable to both of those options,” Hamby said.

Efforts to analyze potential fixes appear to be in the early stages.

The problems came to light at a meeting in Arizona last month. Brenda Burman, general manager of the Central Arizona Project, presented a diagram showing the dam’s eight large tubes, called penstocks, that water normally passes through, as well as the smaller outlet pipes that enable water releases at low reservoir levels.

“They have some unknown issues about how these river outlet works would perform. That’s very difficult new information to hear,” Burman said.

She said officials found sediment, “thinning in the pipes” and “cavitation.” Cavitation refers to the formation and collapse of air bubbles in flowing water and is known to damage propellers, pumps and other structures. Under certain flow conditions, cavitation can pit and tear into metal, damaging the infrastructure.

The Colorado River’s decline threatens hydropower at Glen Canyon Dam. Now, officials are looking at retooling the dam to deal with low water levels.

Federal officials are analyzing how to address the problems, Burman said, adding that the Bureau of Reclamation is “known for being able to come up with engineering solutions to engineering problems.”

“We very much expect to be working with Reclamation in the coming months to investigate exactly what can be done,” she said.

The problems with a crucial part of the dam’s water-delivery system, which were first reported by the Arizona Daily Star, have raised new questions about what sort of fix would be most effective, how much it would cost, and how long repairs could take.

The Colorado River supplies water used by cities, farms and tribal nations across seven states and northern Mexico. The river has long been overallocated, and its average flow has declined dramatically since 2000. Research has shown that global warming is intensifying drought years and contributing significantly to the reduced flows.

The water level in Lake Powell, the nation’s second-largest reservoir, now sits at 33% of capacity — its surface about 68 feet above the lowest level at which the dam can continue generating electricity. The snowpack in the upper Colorado River Basin this year has been above average, and the snowmelt will give reservoir levels a boost for now.

But long-term projections show that substantial reductions in water use will be necessary in the coming years to reduce risks of reservoirs reaching critically low levels.

The infrastructure problems at Glen Canyon Dam add another layer of complications and uncertainty.

Colorado River in Crisis is a series of stories, videos and podcasts in which Los Angeles Times journalists travel throughout the river’s watershed, from the headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to the river’s dry delta in Mexico.

The Bureau of Reclamation detailed some of the agency’s initial steps in a March 26 memo. Richard LaFond, director of the agency’s Technical Service Center, wrote that if the reservoir were to decline below the minimum level for generating electricity, “there are concerns with relying on the river outlet works.”

The latest federal projections show the reservoir is expected to remain above that level for the next two years.

LaFond said his team is using scale models in a laboratory to study how the issues could be addressed.

The Bureau of Reclamation responded to questions from The Times by email, saying the outlet tubes “were not designed to be used indefinitely to deliver water at low elevations.”

“It is important to note that our knowledge will increase as time goes on and that we may need to adjust our actions, as appropriate, consistent with best emerging information, engineering standards, and current science,” the Bureau of Reclamation said.

Some California farmers are urging the federal government to consider draining Lake Powell, supporting environmentalists’ push for a ‘one-dam solution.’

The agency’s officials said while they study the issues, they plan to do maintenance that will include “pipe recoating.” They said they don’t yet have cost estimates for fixes.

Lake Powell has shimmered between red canyon walls along the Arizona-Utah border since Glen Canyon Dam was completed in the 1960s.

Environmental activists, who have long urged federal officials to consider draining the reservoir, said the dam’s internal problems create serious risks of unanticipated water shortages in Southern California, Arizona, Nevada and Mexico.

“We need to have a discussion about how the dam’s antique plumbing could affect 25 million people downstream in low water conditions — especially persistent low water conditions, as we are expecting,” said Kyle Roerink, executive director of the Great Basin Water Network. “We need the bureau to step up and help us all have a better idea of how to fix it.”

Drought and global warming have transformed the Colorado River, making some sections unrecognizable to those who have spent decades on the river.

Roerink’s organization, together with the Utah Rivers Council and Glen Canyon Institute, had warned in a 2022 report that the “antiquated plumbing system inside Glen Canyon Dam represents a liability,” with risks of precisely the type of problems that have come to light.

Roerink called for the Biden administration to bring its analysis of Glen Canyon Dam’s vulnerabilities into its ongoing process of considering long-term plans for reducing water use.

The Bureau of Reclamation plans to analyze alternatives for new rules to govern river management starting after 2026, when the current rules expire.

The federal government has received separate proposals from the upper and lower basin states, tribes, environmental groups and water researchers.

The risk of a choke point at Glen Canyon Dam not only increases uncertainty, Roerink said, but also “sets up potential for more acrimony.”

He said there should be an open discussion, as part of the federal review, to analyze the problem and what can be done about it.

That would “create an opportunity for the public to vet, scrutinize and understand everything that the bureau knows, and also consider the known unknowns as well,” Roerink said. “Let’s talk about uncertainty, and what that could mean.”

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.