With climate change compounding the strains on the Colorado River, seven Western states are starting to consider long-term plans for reducing water use to prevent the river’s reservoirs from reaching critically low levels in the years to come.

But negotiations among representatives of the states have so far failed to resolve disagreements. And now, two groups of states are proposing competing plans for addressing the river’s chronic gap between supply and demand.

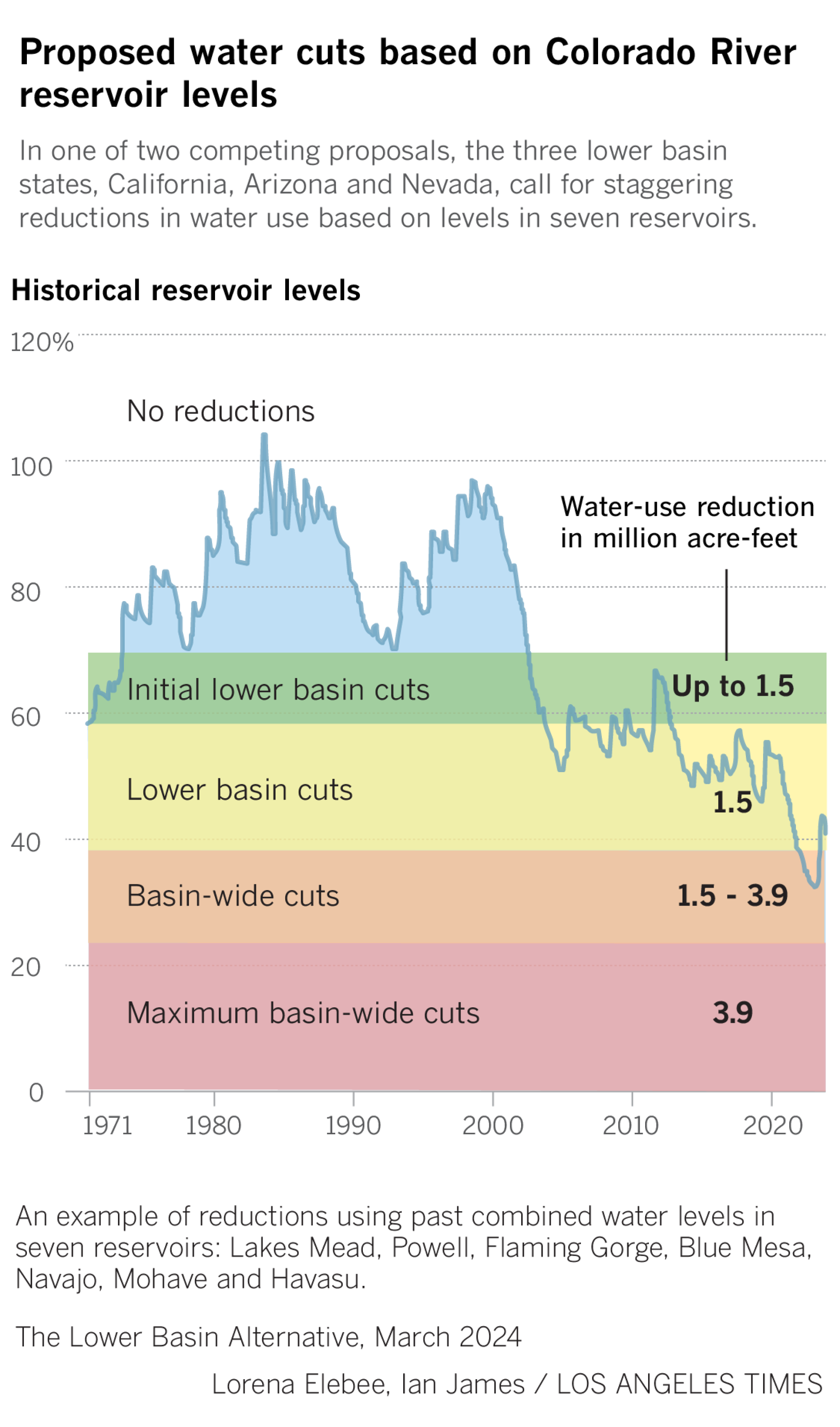

In one camp, the three states in the river’s lower basin — California, Arizona and Nevada — say their approach would share the largest-ever water reductions throughout the Colorado River Basin to ensure long-term sustainability.

In the other camp, the four upper basin states — Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico — argue their proposal would help rebuild reservoir levels and enable the West to adapt to the limits of diminished river flows.

The two sides disagree on how triggers for mandatory cutbacks should be determined, and how the reductions should be apportioned between the lower basin and the upper basin.

Representatives of California, Arizona and Nevada say the upper states’ proposal is unworkable because it would require the lower states to shoulder the burden of the cuts, while the lower basin’s proposal would spread the cuts throughout the region when reservoirs reach low levels.

“Our proposal requires adaptation and sacrifice by water users across the region,” said J.B. Hamby, California’s Colorado River commissioner. “It is all of our collective responsibility. Putting the entire burden of climate change on one basin or another will result in conflict. And we can do better than that.”

The states submitted their proposals on Wednesday to the federal Bureau of Reclamation, which plans to analyze alternatives for new rules to govern river management starting after 2026, when the current rules expire.

Hamby, who spoke at a briefing with counterparts from Arizona and Nevada, says the three states’ proposal would respond to the effects of climate change, resolve the “structural deficit” in water supplies, and manage the entire river system as a whole. He said California and Arizona, which have been at odds in the past, have agreed to “cooperatively manage massive reductions, and share in the pain, because it’s necessary.”

“Implementing our alternative will be extraordinarily difficult. It will represent billions of dollars in investments to manage the reductions,” Hamby said. “We’re proposing it anyway. Because that’s what we must do if we want a sustainable Colorado River Basin for future generations.”

Under their proposal, California, Arizona and Nevada would agree to mandatory reductions in water use of up to 1.5 million acre-feet per year in response to a broad range of reservoir levels. The plan is for Mexico to share in these reductions — a proposal that would need to be negotiated separately — but the initial phases of cuts would not apply to the upper basin states.

If the levels of seven reservoirs were to fall below a critical threshold of 38% full, the cuts would increase to as much as 3.9 million acre-feet per year, with the upper basin states sharing in the reductions.

The proposed framework for scaling back water usage would add to ongoing cuts under existing agreements, and would translate into forgoing a large share of the 15 million acre-feet that was originally divided among the states under the 1922 Colorado River Compact. (For comparison, U.S. states used more than 11 million acre-feet of Colorado River water in 2020, while Mexico used about 1.5 million acre-feet.)

Leaders of the four upper states are calling for a different approach, saying their proposal would address imbalances in the water supply and boost water levels in Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the river’s largest reservoirs, to ensure sustainable supplies.

“We can no longer accept the status quo of Colorado River operations,” said Becky Mitchell, who represents the state of Colorado on the Upper Colorado River Commission. “If we want to protect the system and ensure certainty for the 40 million people who rely on this water source, then we need to address the existing imbalance between supply and demand.”

The upper states’ proposal would base water usage reductions on the levels of Lake Powell and Lake Mead, without factoring in the levels of five smaller reservoirs, as the lower states are proposing.

Under the upper basin proposal, California, Arizona and Nevada, the lower basin states, would face mandatory annual cuts of 1.5 million acre-feet under most scenarios, or about 20% of their full allotment.

If the two largest reservoirs were to drop below a critical threshold, the lower states would face gradually increasing cuts of as much as 3.9 million acre-feet per year.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

The upper states say in their proposal that because water users in their region largely depend on snowmelt rather than water releases from reservoirs, they already regularly face serious shortages.

“We are on the front lines of climate change without the protection of massive reservoirs,” Mitchell said in an email. “This means that when water is not available, we cannot use it, so a cut has already occurred.”

“This is a much different reality than that of Lower Basin water users, who have been provided a level of certainty in water deliveries by drawing down Lake Mead,” she said.

She added that the lower states have been “shielded from the impacts of climate change” as they’ve relied on large releases of water and drawing down Lake Mead for years.

She pointed out that in 2000, the reservoirs were nearly full.

“We must account for the fact that our country’s two largest reservoirs are now depleted to critically low levels,” Mitchell said. “The focus must be on living within the means of the river.”

The water level behind Hoover Dam in Lake Mead, the country’s largest reservoir, is now at 37% of capacity. Upstream on the Utah-Arizona border, Lake Powell stands at 34% full.

The river’s average flow has declined dramatically since 2000, and research has shown that global warming is intensifying drought years and contributing to reduced flows.

The Colorado River is approaching a breaking point, its over-tapped reservoirs dropping. Years of drying have taken a toll at the river’s source in the Rockies.

Scientists have found that roughly half of the decline in the river’s flow this century has been caused by rising temperatures, and that for each additional 1.8 degrees of warming, the river’s average flow is likely to decrease by about 9%.

The four upper states’ proposal is designed to substantially boost reservoir levels, avoid large variations in water releases, and “provide greater certainty to the system,” Mitchell said.

Those representing California, Arizona and Nevada say they’re concerned that the upper states’ proposal would make them shoulder the entire burden of water cuts.

“What I need to see out of the upper basin is a proposal in which they help contribute to the protection of the river system, and in a way that has certainty,” said Tom Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources. “I think that’s the first step: ... a recognition that we share the burden of protecting this system, and that there is some equity in the upper basin coming together with us and contributing.”

Water managers representing Arizona, California and Nevada say their proposed framework aims to address the loss of water caused by evaporation from reservoirs and seepage from the river in the lower basin, which a federal report recently estimated amounted to 1.3 million acre-feet annually.

Federal officials say short-term risks have eased on the Colorado River, providing ‘breathing room’ for talks on long-term plans to adapt to climate change.

John Entsminger, general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, says the three states did modeling of their proposal based on projections into the 2060s.

“We want a long-term, durable operating regime that addresses the impacts of drought and climate change, but also provides certainty and predictability for all of the water users on the Colorado River,” Entsminger said. “It is a basin-wide problem and it requires a basin-wide solution.”

Not represented in the states’ proposals were the 30 tribes of the Colorado River Basin, who have rights to use nearly one-fourth of the river’s average supply, and who have sought greater involvement in talks on future water management. Representatives of tribes said they were reviewing the states’ proposals.

Buschatke says he and other state officials consider the tribes crucial partners in developing plans for reductions in water use.

Jordan Joaquin, president of the Quechan Tribal Council, praised the lower basin states’ proposal, calling it a “thoughtful plan for addressing the structural deficit.” He said it’s essential that the post-2026 management framework provides for the needs of people and ecosystems, protects tribal water rights and preserves the river.

The states released their plans a day after the Biden administration announced that ongoing conservation efforts supported by federal funding, together with ample snow and rain over the last year, have substantially reduced the risks of reservoirs declining to critically low levels between now and 2026.

Some environmentalists say that while a wet year and short-term conservation efforts have temporarily eased risks of a damaging crash on the river, long-term concerns remain.

Journalists from the Los Angeles Times travel along the Colorado River to examine how the Southwest is grappling with the water crisis.

Kyle Roerink, executive director of the Great Basin Water Network, said last year’s above-average snowpack in the Rocky Mountains “was a blessing and a curse.”

“It undoubtedly gave negotiators breathing room, which deflated some of the urgency,” he said. “But the saving grace is the 2026 deadline. No one can outrun that.”

The Bureau of Reclamation plans to complete a draft environmental review of alternatives to the long-term rules by the end of this year. And federal officials have said they will continue to participate in talks through the spring and summer to try to achieve as much consensus as possible.

The states’ proposals represent a “start towards meaningful negotiations to get the basin to long-term sustainable management,” said Mark Gold, director of water scarcity solutions for the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council.

Gold said the cutbacks ultimately will need to be much larger than 1.5 million acre-feet per year, “but to actually put that out there is positive.” He said while the lower states use the most water and will need to shoulder much of the cuts, the upper states’ participation is also vital.

“The solution for the Colorado River Basin needs to include everyone within the basin,” Gold said. “We’re talking about long-term sustainable management. That can only happen if everybody does their part. And there’s a lot more that needs to be done — on everything from water reuse to conservation to eliminating wasteful uses within the Colorado River Basin — that everybody could do better.”

Democratic Sen. Alex Padilla of California said the lower basin states’ proposal provides for sustainable management of the river “that meets the scale and urgency that the climate crisis demands.” He urged the upper and lower basin states to “work together to reach consensus.”

Officials on both sides of the debate say they plan to continue talks to try to reach a seven-state consensus.

Mitchell, of Colorado, said that in the past, the seven states “have always been most successful through collaboration.”

Hamby, California’s commissioner, said the states will continue working toward a consensus, though for now a “chasm” remains to be bridged.

“Arguing legal interpretations until we’re all blue in the face doesn’t do anything to proactively respond to climate change,” he said. “Protecting the basin is a joint responsibility.”