Tribes seek greater involvement in talks on Colorado River water crisis

As the federal government starts negotiations on long-term plans for the overtapped Colorado River, leaders of tribes are pushing for more involvement in the talks, saying they want to be at the table in high-level discussions among the seven states that rely on the river.

The 30 tribes in the Colorado River Basin have rights to use roughly one-fourth of the river’s average supply. But over the past century, leaders of tribal nations were largely excluded from regional talks about river management, and only in recent years have they begun to play a larger role.

Leaders of several tribes say they continue to be left out of key talks between state and federal officials, and they are demanding inclusion as the Biden administration begins the process of developing new rules for dealing with shortages after 2026, when the current rules are set to expire.

“They’ve met, they’ve discussed, they’ve made decisions that we only find out afterwards,” said Gov. Stephen Roe Lewis, leader of the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona. “And the 30 tribes — and I’ve heard this from my fellow tribal leaders — they are very frustrated by that, especially as we look at a post-2026 process moving forward.”

The Interior Department on June 15 initiated the process of developing new long-term rules for operating reservoirs and apportioning water cuts during shortages. New rules will need to be in place by the end of 2026, when the current 2007 guidelines expire.

The federal government’s action sets the stage for difficult negotiations over how cities, farming regions and tribes across seven states can address chronic overuse and adapt as global warming continues to diminish the river’s flows.

The pivot to negotiating the post-2026 rules was announced three weeks after representatives of the states agreed on a proposal to cut water use over the next three years, a stopgap measure intended to temporarily prevent reservoirs from dropping to critically low levels.

During the upcoming talks, Lewis said he and other Native leaders want to see the federal government include representatives of the 30 tribes whenever they convene a meeting with all seven states. He said this approach wouldn’t stop state representatives from meeting among themselves.

Lewis raised the concern at a conference in Boulder, Colo., this month, saying that as work begins on a post-2026 plan, “it’s no longer acceptable for the U.S. to meet with seven basin states separately, and then come to basin tribes, after the fact.”

He said when leaders of the tribes met with Interior Secretary Deb Haaland last year, she made a commitment “that we would be at the table when these highest-level decisions were being made.”

As climate change and overuse threaten the Colorado River, Native American tribes seek a larger role in the river’s stewardship.

The Gila River Indian Community holds a large water entitlement in Arizona and has agreed to leave a portion of its water in Lake Mead over the next three years while receiving $150 million from the federal government. The community, which uses Colorado River water to irrigate farmland on their reservation, will also receive $83 million to expand water reuse with a reclaimed water pipeline project, and is working with the federal government on a project to cover some of its canals with solar panels.

“When tribes are at the table, tribes can bring solutions, can bring innovation. And it benefits the whole region,” Lewis said in an interview with The Times.

The Interior Department said the process of developing new rules to replace the 2007 guidelines will involve “robust collaboration” between the seven states, tribes, other stakeholders and Mexico.

The department formally initiated the process by publishing a notice in the Federal Register laying out its plan to conduct a review and release a document called an environmental impact statement. The notice says the aim is to develop new guidelines and strategies that are “robust and adaptive and can withstand a broad range of future conditions,” including preparing for continued drought, reduced runoff and low reservoir conditions.

For the next two months, until Aug. 15, the Interior Department and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation will accept comments from the public on how the existing rules should be changed to “provide greater stability to water users and the public throughout the Colorado River Basin.”

Deputy Interior Secretary Tommy Beaudreau said the Biden administration has “held strong to its commitment to work with states, Tribes and communities throughout the West to find consensus solutions in the face of climate change and sustained drought.”

The effort needs to start now “to allow for a thorough, inclusive and science-based decision-making process,” said Reclamation Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton.

As states agree to leave more water in the Colorado River reservoir, Native tribes get more involved after a history of being left on the water management sidelines.

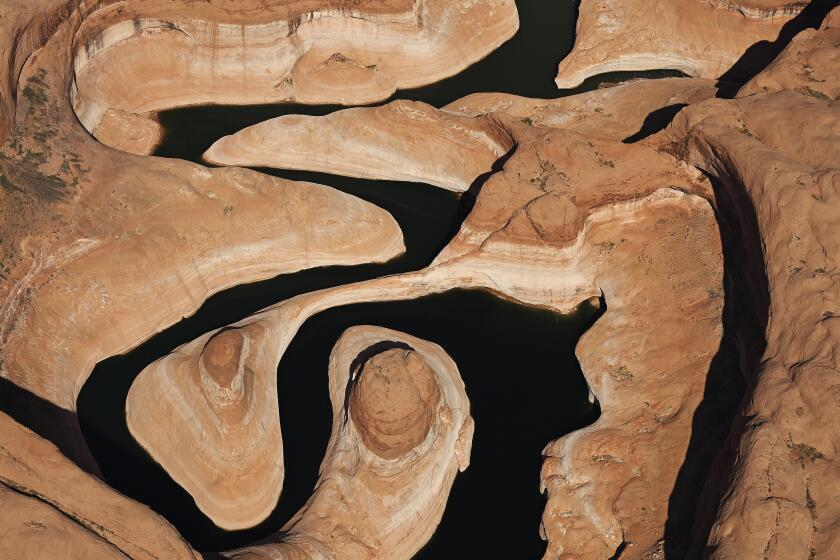

The river’s largest reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, have declined to their lowest recorded levels during 23 years of drought worsened by climate change. As rising temperatures have intensified the drying of the watershed, the river’s flow has declined about 20% below the average prior to 2000.

Storms this winter left the Rocky Mountains with one of the largest snowpacks in years, and the runoff is starting to boost reservoir levels.

Speaking this month at the conference at the University of Colorado School of Law, Touton said the runoff this year is projected to be more than the flows in the last three years combined. However, she said, “there are no guarantees that this is more than a one-off amidst a larger context of continuing drought and aridification.”

The river’s depleted reservoirs are now at 42% capacity. Touton said addressing the water deficit and coming up with long-term solutions will present difficult challenges.

“The next step will be the hardest thing in the history of our organization, and that the basin has experienced,” Touton said. “We must continue to work together through these difficult decisions.”

Colorado River in Crisis is a series of stories, videos and podcasts in which Los Angeles Times journalists travel throughout the river’s watershed, from the headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to the river’s dry delta in Mexico.

The history of Indigenous peoples’ exclusion from decisions about the river goes back to the signing of a 1922 compact that divided the water among the states.

A century ago, “we weren’t at the table. We weren’t even U.S. citizens at the time. But now we are,” said Jordan Joaquin, president of Quechan Tribe of the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation.

“Tribes should be at the table,” Joaquin said. “We will be at the table for post-2026. It’s meaningful to us. It’s the right thing to do.”

Joaquin was recently appointed as a member of California’s Colorado River Board by Gov. Gavin Newsom, becoming the first representative of a Native tribe to serve in the role.

The Quechan Tribe, whose reservation lies along the river in California’s southeast corner, has been participating in a program in which some farmlands are left dry and unplanted for part of the year in exchange for payments, helping to boost the levels of Lake Mead.

Many Indigenous leaders have stressed that their perspectives can play a vital role in rethinking the region’s relationship to the river.

Nora McDowell, a leader of the Fort Mojave Indian Tribe, made an impassioned plea for the involvement of tribes and protecting the river during a speech at the conference.

“We continue to not have a voice and not have a seat, and not have a chance to help think about these things, and to take into consideration the cultural, the spiritual, and the health and the environment of that river,” said McDowell, a former tribal chairperson.

The Mojave people, whose lands straddle the river in Nevada, Arizona and California, feel a deep spiritual connection to the Colorado River and the ecosystem that depends on it, but that the dams and heavy water diversions have exacted a major toll, she said.

“If that river could speak today, what would it say? ‘You guys pretty much screwed up,’” McDowell said.

“We have to be here to speak for it. And I know it would say, ‘Respect me. Take care of me. Let me heal,’” she said. “‘Don’t let me die.’”

Seven states have agreed to cut water use to boost the Colorado River’s depleted reservoirs, reaching a consensus after months of negotiations.

McDowell said protecting the river will require changing how it’s managed. “We have to think about sustainability in different ways,” she said. “We all have a place and a voice that needs to be heard, that needs to be taken into consideration, that needs to be a part of the solution.”

Even as tribes seek greater involvement, many are struggling to secure water rights and basic infrastructure to supply their citizens. Of the 30 federally recognized tribes in the Colorado River Basin, 11 tribes still have unresolved water rights claims.

In the Navajo Nation, an estimated 30% or more of people live in homes without running water. In Hopi communities, many people have tap water contaminated with toxic arsenic.

Environmental advocates have also emphasized that tribes must have seats at the table.

Jon Goldin-Dubois, president of Western Resource Advocates, said many of the tribes’ water rights, infrastructure and values have long been denied and now “must be included in the decision-making process and have equitable access to clean drinking water.”

The water savings that will be needed to address the long-term gap between supply and demand on the river are expected to require substantial reductions in water use in agriculture, which consumes the largest share of the water, as well as new measures to boost conservation and efficiency in cities from Phoenix to Los Angeles.

Goldin-Dubois said cities, farms and other businesses throughout the region should take steps to cut water use by at least 25% immediately, and with the exception of tribes, new development that would require more water from the river should be taken “off the table until a sustainable path has been identified.”

The upcoming negotiations will also involve questions about how the current system of managing dams and apportioning water can be revamped to adapt to climate change. Scientists have projected the river’s average flow could decrease as much as 30% to 40% by mid-century as temperatures continue to rise.

Brad Udall, a water and climate scientist at Colorado State University, said he hopes the upcoming process will clearly lay out the flow declines the region must prepare for. Udall said the crisis also underlines the urgent need to eliminate carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels.

“We’ve got to get these emissions down as fast as we humanly can,” Udall said.

Kathryn Sorenson, director of research at Arizona State University’s Kyl Center for Water Policy, said tribes have shown great willingness to work on solutions, and she expects they will play a positive role.

“We know the flows of the river are going to diminish. And we know the river is overallocated, and all those issues come due post-2026,” Sorenson said.

As tribes have a stronger voice in the discussions, that will benefit the process by bringing diverse perspectives, Sorenson said.

“Old ways of thinking are not going to solve new problems,” she said.