MAMMOTH MOUNTAIN — For much of the last 18 years, Vincent Valencia has lived alone at the summit of Mammoth Mountain — a frozen world that is lashed regularly by the ugliest weather California has to offer.

At 61, he is one of the few people with the obscure skill set needed to supervise Mammoth Mountain Ski Area’s gondola operation, which often endures whiteout conditions, 184-mph winds and temperatures that drop to minus 30 degrees.

“I may not see another living soul for five days or more,” Valencia said recently. “I’m by myself and not doing anything stupid.”

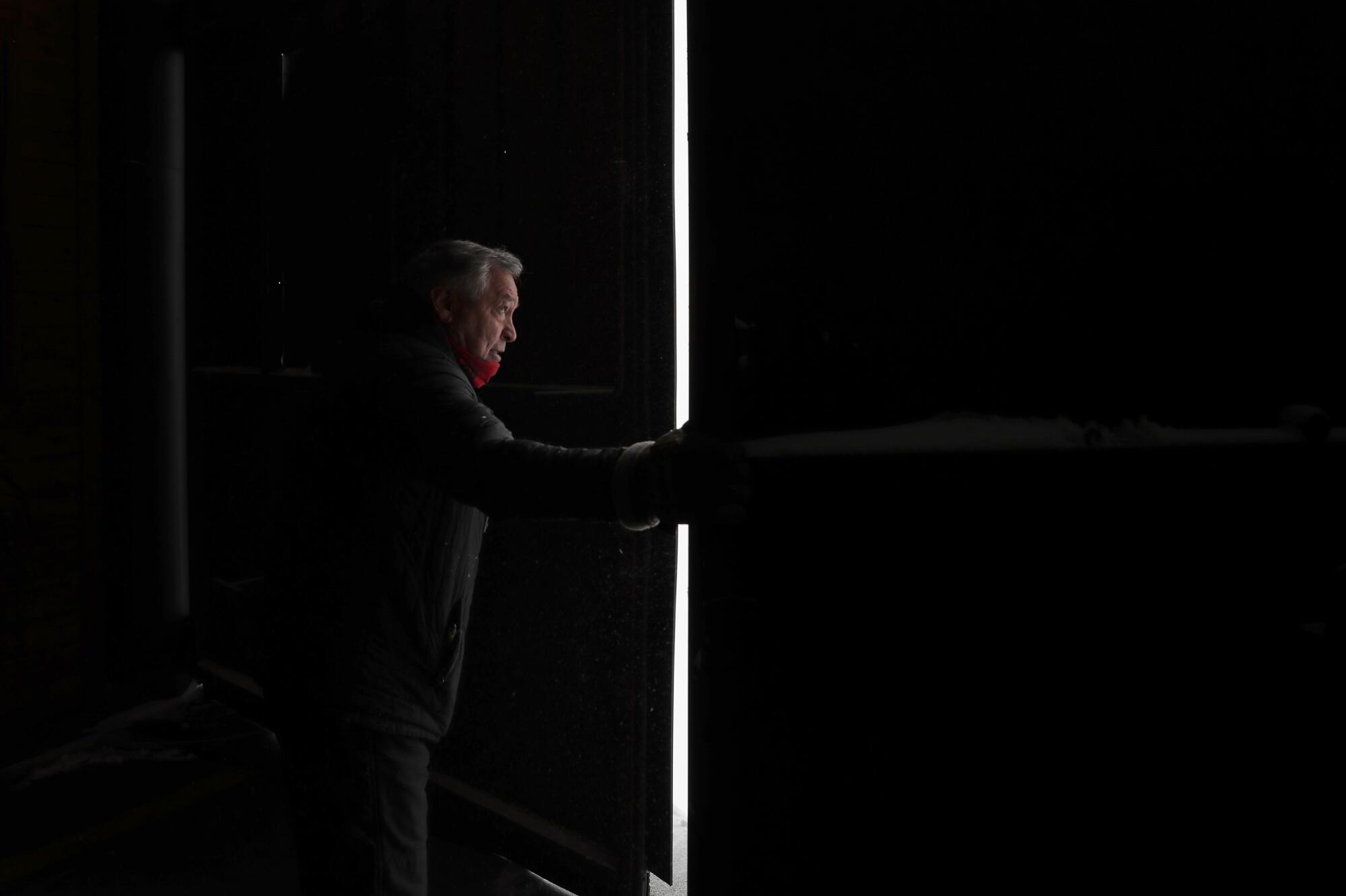

A confident man with tousled gray hair and an easy smile, Valencia was busy preparing for a major snowstorm — the second to bite the eastern Sierra Nevada in less than a month.

Plans for a $650-million makeover of the Los Angeles Zoo have angered environmentalists, who say it would destroy native woodlands.

“A social butterfly isn’t going to like this job,” he said. “But that’s not me.”

At the mountain’s summit, heightened awareness and obsessive preparedness fill the void of conversation on the massive extinct volcano with steep chutes on all sides that catch storms like a sail.

A simple accident such as a slip on the ice is not a mere inconvenience. But like all living things in frigid climes he has adapted to the cold and snow that drape the gondola’s final stop on a mountain that annually attracts more than 1 million skiers, most of them from Southern California.

When a major storm clamps down, gondola operations are halted and Valencia retreats to his lair tucked beneath the facility’s massive pulleys, gears, steel girders and 2-inch-thick cables to stay warm by a heater while the sounds of the Talking Heads issue from a boom box.

He taps his boot to it, scans digital displays of the windspeed, wind direction and temperature outside, and wonders whether to microwave some of his mother’s frozen homemade tamales again for dinner.

Given Valencia’s mountainous responsibilities and decades of experience, his recent decision to retire in two years — as he put it, “while I’m still healthy and strong” — chilled Ski Area officials to the bone.

“The big question now is this: What are we going to do when Vinnie leaves?” said Chris Bulkley, vice president of mountain operations for the Ski Area. “The answer is we don’t know. He’s going to be a tough person to replace.

“Vinnie is dedicated, responsible and almost superhuman during colossal storms,” he said. “I’ve never heard him say, ‘I can’t do it.’

“We may have to replace him with a team effort,” he added.

Conservationists worry that a proposed high-speed, electric rail line connecting Southern California and Las Vegas will harm bighorn sheep.

In the meantime, the hub of Valencia’s life during the ski season is his rent-free, 700-square-foot apartment.

“I’ve got all the conveniences, including a generator when the power is out,” he said.

Inside, there are no photos or posters on the walls. No guitar in the corner. Just an old telescope he uses when the weather allows him to admire the planets and stars glinting diamond, ruby and sapphire.

There is no mailbox outside. Just a sign designating what Valencia describes as “my world”: Mammoth Mountain: 11,053 feet above sea level.

Once, he said, the aurora borealis danced across the night sky, and it shimmered off a vast blanket of snow and ice.

Of course, Valencia has a UFO story to tell. In the dark before sunrise one day in 2009, he said he watched in amazement as “a bright white orb flew in low from the northeast at treetop level, maneuvering along valleys and gorges before disappearing behind a ridgeline.”

“It was one of those things you can’t explain,” he said, shaking his head, “and something I will never forget.”

When windblown snow hits its peak, as it did early one day recently, Valencia is in his element, and as alert and keenly aware as possible.

With energy and concentration that seem inexhaustible, he inspects machinery; confers with ski patrol members; listens to dispatches crackling over a two-way radio attached to a belt loop; helps load and unload skis; and sweeps snow off stairwells and away from emergency exits.

At a time when post-pandemic adventure travel beckons, Valencia knows that passengers boarding gondola cars — which costs $39 round trip — are seeking exhilaration as they soar over icy forests, granite chasms and escarpments.

Depending on the weather, that can either be a breeze or a frightful ordeal.

“Lots of people literally weep with joy, overwhelmed by the mountain beauty they see in every direction,” he said. “But some others discover they are terrified of heights and have to be transported down the mountain on a snowmobile because they are too nauseated or scared to get back on the gondola.”

Through it all, “Vincent runs a tight ship,” said Ralph Byrne, 53, a longtime ski patrol member. “He’s a risk manager on top of the world.”

When powerful winds become unsafe for the gondola to operate, Valencia has the authority to close it down and send staffers home until conditions improve.

Such was the case one winter day under clear blue skies, Valencia recalled, “when gale-force crosswinds were so strong I had to crawl on my hands and knees from a snowmobile to my apartment to keep from being blown off the mountain.”

Then there is the Ski Area’s time-tested approach for dealing with unstable avalanche hazards: It blasts them with a World War II-era 105-millimeter howitzer leased from the U.S. Army.

Before the fearsome gun fires on carefully calibrated targets including popular ski runs in a potential avalanche path, Valencia said, “I get a call reminding me to get inside because of the shrapnel.”

A short while later, the “whump” of an impacting shell drifts over the face of the mountain.

Valencia grew up in Redondo Beach and surfed up and down the coast. As a young man he roamed the eastern Sierra Nevada and skied Mammoth Mountain with friends.

In the early 1990s, an ad in a weekly newspaper caught his attention: “Mammoth Mountain hiring in all positions. Live the lifestyle!”

He was hired by Dave McCoy, the now-deceased pioneer of the California ski industry, who — with vision, hard work and a knack for the mechanical — transformed the remote Sierra peak into a storied destination.

“I started work as a salesman in a sports shop,” Valencia said, “then worked my way up to gondola operator and eventually supervisor.”

His wife and daughter lived with him on the mountain until 2011, when, he said, they moved in with her parents in West Los Angeles. “My wife didn’t like the winters,” he said.

Now, Valencia is making plans to move down the mountain and resume full-time life with his wife and daughter in his hometown.

“This is a young man’s job,” he said, with a kinetic spirit shining in his eyes. “If one of these days I’m alone up here with a bum knee, well, that may not be a good deal.”

But after nearly two decades of making a living by keeping people safe and satisfied in an alpine wilderness raked by wildly unpredictable winds and whiteout conditions, can Valencia adapt to a new life in the laid-back palm latitudes of Redondo Beach?

Gazing out at the snowfields and glaciers covering the raggedy High Sierra wilderness, Valencia acknowledged that is a tough question to answer.

“Maybe so, maybe not,” he said. “We’ll see.”