Remember the Aliso Canyon disaster? SoCalGas just tried to delay safety tests

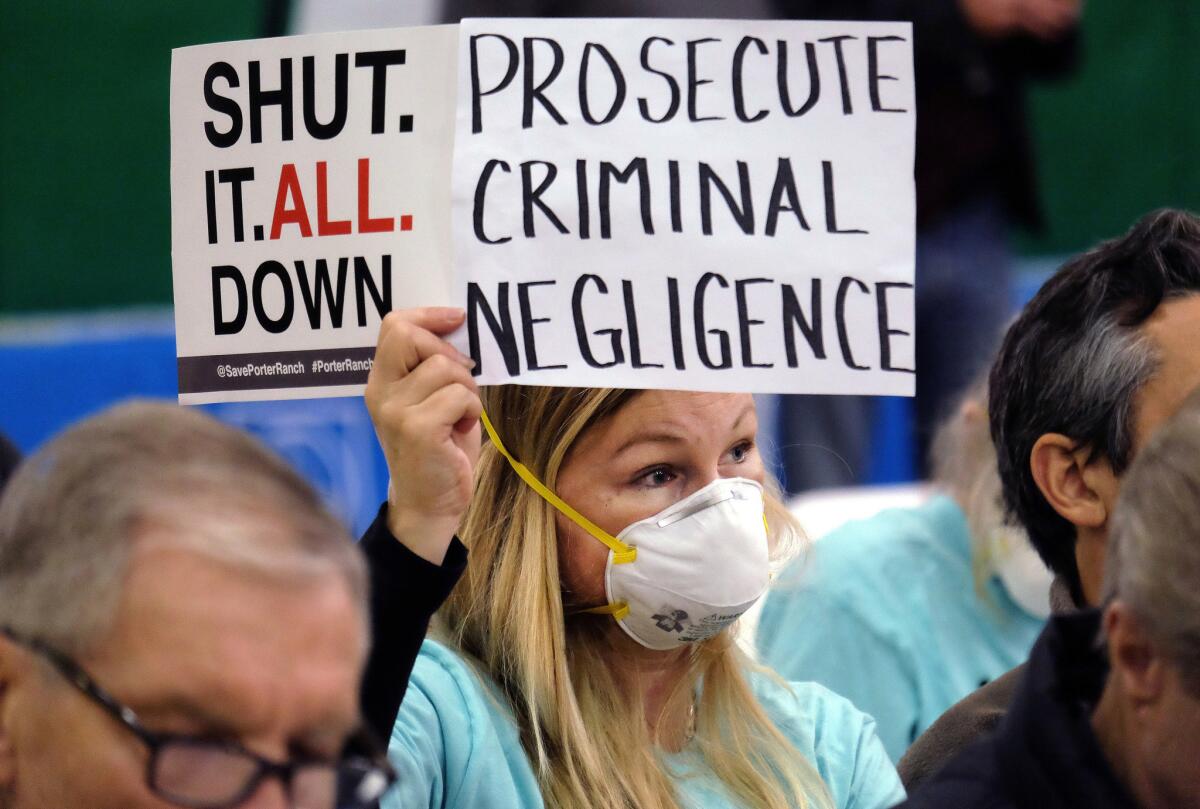

State regulators have blocked Southern California Gas Co.’s effort to delay required safety testing at the company’s Aliso Canyon storage field, the site of a record-setting gas leak that spewed more than 100,000 tons of heat-trapping methane into the atmosphere and sickened residents of the nearby Porter Ranch neighborhood.

The company asked Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration to temporarily suspend a requirement that all gas storage wells at Aliso be tested every two years, citing the COVID-19 pandemic and associated stay-at-home orders, newly released documents show.

The state’s oil and gas regulator, known as CalGEM, denied the request Monday.

State Oil and Gas Supervisor Uduak-Joe Ntuk said in a letter that the well testing requirements “are a central part of the comprehensive regulations that CalGEM adopted in response to the Aliso Canyon well blow out incident, and they are central to CalGEM’s commitment that all possible steps will be taken to ensure safe operation of underground gas storage projects.”

“CalGEM understands that compliance with the [mechanical integrity testing] requirements for gas storage wells are challenging and that COVID-19 has compounded that challenge,” Ntuk wrote. “Nonetheless, adherence to the recently adopted regulations is essential and CalGEM will only approve changes in testing frequency that are consistent with the regulatory framework.”

The request from SoCalGas for a six-month extension hasn’t previously been reported.

Your guide to our clean energy future

Get our Boiling Point newsletter for the latest on the power sector, water wars and more — and what they mean for California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

SoCalGas executive Rodger Schwecke highlighted the very safety rules the company was simultaneously working to delay in a June 4 interview with The Times — less than three weeks after the utility’s most recent request for delayed enforcement.

Schwecke said the requirement that all wells be tested every two years was part of an enhanced safety regime that had made Aliso Canyon and the gas company’s other underground storage fields “the safest in the state, if not the safest in the nation.”

“Of the 66 wells that we currently have available at Aliso Canyon, we’re going to have 30 or 40 of them reassessed this year — and they are required to be assessed every two years,” Schwecke said at the time.

Issam Najm, president of the Porter Ranch Neighborhood Council, said in an email that the gas company’s request to delay well testing is “yet another example of how SoCalGas appears to treat safety measures as mere regulatory burdens, instead of integral components of the responsible operation of a hazardous facility such as Aliso Canyon.”

In an emailed statement, SoCalGas spokeswoman Christine Detz said the company “is ahead of all other operators in the state, fully completing its baseline assessments for all its underground gas storage wells earlier than required by regulatory requirements.” The utility is already proceeding with its next round of well testing, which must be completed by Oct. 1.

“We believe a six-month extension for completing the second round of assessments does not pose a safety risk, while supporting the reliability of natural gas service to customers this coming winter,” Detz said. “However, we will meet the Oct. 1, 2020, date.”

Aliso Canyon has become a flashpoint in a debate over how quickly Califorina might phase out natural gas, a planet-warming fossil fuel used for heating, cooking and electricity generation. SoCalGas, a shareholder-owned utility that serves 22 million people, has mounted a forceful campaign to maintain its role in powering society and considers Aliso a key tool for maintaining reliability and limiting costs to consumers.

Newsom has said he’s committed to shutting down Aliso, and last year he asked the state’s Public Utilities Commsion to “expedite planning” for its closure. But in the meantime, the commission has allowed SoCalGas to ramp up use of the facility dramatically since Newsom took office in 2019, compared to the two years after the October 2015 blowout, when Aliso was hardly used at all.

Southern California Gas is engaged in a wide-ranging campaign to preserve the role of its pipelines in powering society.

In a letter to Newsom on Monday, three L.A.-area lawmakers — state Assemblywoman Christy Smith, state Sen. Henry Stern and U.S. Rep. Brad Sherman — urged the governor to direct the utilities commission “to immediately act to prevent future unnecessary withdrawals from Aliso Canyon.”

“Overreliance on the facility sets the dangerous precedent of delaying the phase-out of facility use ahead of its proposed closure dates, and needlessly delays the transition to the state’s future renewable energy supply goals,” the lawmakers wrote.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times.

An in-depth analysis commissioned by state officials determined the October 2015 blowout was caused by a faulty well casing at the former oil field, nestled in the Santa Susana Mountains just north of Los Angeles city limits. The outer casing of well SS-25 ruptured due to microbial corrosion caused by contact with groundwater, the consulting firm Blade Energy Partners found.

Blade concluded SoCalGas “did not conduct detailed follow-up inspections or analyses after previous leaks” at Aliso Canyon going back to the 1970s and “lacked any form of risk assessment focused on well integrity management,” according to a Public Utilities Commission summary of the consultant’s findings. The consultant also found that “updated well safety practices and regulations adopted by [CalGEM] address most of the root causes of the leak” identified during its investigation, the commission wrote.

One of those regulations is the requirement that all wells undergo mechanical integrity tests at least once every two years.

In a March 23 letter to CalGEM, SoCalGas executive Gina Orozco described the gas company’s concerns “over the continuation of certain activities not deemed critical or essential for safe, reliable delivery of natural gas service under these exigent circumstances,” referring to the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, Orozco wrote, “SoCalGas requests that CalGEM consider a temporary stay of enforcement for two-year well reassessments” at the utility’s underground storage facilities, including Aliso.

“This temporary suspension will enable employees, contractors, and agency personnel, who need to witness certain activities related to this work, to fully engage in federal, state, and local social distancing and ‘stay home where possible’ orders,” she wrote.

Orozco did not suggest a timeframe for lifting the requested temporary suspension. But she did urge the oil and gas regulator to approve a “risk management plan” that SoCalGas submitted in 2019, under which the company might test some wells at Aliso no more than once every 10 years, rather than every two years, based on an assessment of the risks posed by each well.

When CalGEM didn’t grant those requests, the utility tried again.

SoCalGas executive Paul Goldstein wrote to CalGEM on May 18 requesting a six-month enforcement delay, which would extend the deadline for the next round of well integrity tests from Oct. 1, 2020 to April 1, 2021. In addition to discussing the effects of the pandemic, Goldstein wrote that the extension “would protect the gas deliverability for our customers this upcoming winter.”

That claim echoes previous arguments the gas company has made for state officials to allow greater use of Aliso Canyon.

The Public Utilities Commission has partially loosened its restrictions on Aliso. But SoCalGas has argued that continued limits on gas withdrawals can create supply constraints that at times have forced consumers to pay more for energy, including during a summer 2018 heat wave when price spikes landed Southern Califonria Edison customers with an unexpected $850-million bill.

The gas company’s critics counter that there would be no supply constraints — and no price spikes — if SoCalGas could fix a key pipeline that runs through the desert toward Los Angeles. The pipeline has been out of service most of the last three years.

Critics also say SoCalGas has a financial interest in convincing regulators that Aliso is needed to provide cheap, reliable energy. The facility was worth $769 million to the gas company’s corporate parent, San Diego-based Sempra Energy, at the end of 2019. As long as it remains in use, SoCalGas customers will be on the hook to pay off the company’s investment, plus shareholder profits.

Hollin Kretzmann, an attorney at the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity, slammed SoCalGas for promoting the two-year testing requirement to the public even as it quietly asked regulators for permission to reassess storage wells at Aliso less frequently.

“That company is the last company that should get a pass on safety and environmental regulations,” he said.

The company has been charging California ratepayers for some contributions to pro-natural gas advocacy groups.

In the gas company’s May 18 letter, Goldstein said the requested enforcement delay would apply only to wells that have already passed baseline inspections. He also cited new federal guidelines that don’t require gas storage wells to be tested every two years.

“The industry and experts continue to evaluate the risk of well entry inspections. While this research is still new and ongoing, to date there has not been any fact-based or science-based research affirming that two-year well reassessment intervals requiring well entry decreases the risk of damage to life, health, property, or natural resources,” Goldstein wrote.

CalGEM posted the utility’s letters — as well as other requests from oil and gas companies seeking to extend regulatory deadlines due to COVID-19 — on its website last week. A spreadsheet shows the agency has approved six requests, rejected 18 and is still considering 13 others, including one from the oil giant Chevron to delay remediation for 19 wells in Kern County by one year.

State officials fined Chevron $2.7 million last year after a Kern County spill that saw more than 1.3 million gallons of oil and wastewater seep into a dry creek bed from one of the company’s wells at the Cymric Oil Field, about 35 miles west of Bakersfield.

If crude oil spills in California oil country, does anyone care? In the Kern County town of McKittrick, they say it’s just the price of doing business. They want everyone to stop fussing over a Chevron well that’s leaked a million gallons of oil and water in nearby Cymric oil field.

One of California’s other major gas utilities, Pacific Gas & Electric, made a request similar to the one submitted by SoCalGas, for its McDonald Island storage field in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta.

PG&E acknowledged it had already expected to have trouble completing its planned 2020 well inspections even before the pandemic. But with COVID-19, PG&E wrote, the company “anticipates the well work schedule ... to be impacted such that completion of the well work” is unlikely to be achieved by Oct. 1.

CalGEM says it’s still considering PG&E’s request.