After Aliso Canyon, a gas pipeline exploded — costing Californians $1 billion

Two years after methane gas began leaking from Southern California Gas Co.’s Aliso Canyon storage field, one of the company’s key pipelines exploded, starting a fire in the desert and leaving a smoking crater in the ground.

Nobody was hurt, and the October 2017 explosion went largely unnoticed outside the energy industry.

But the damaged pipeline was taken out of service — severely constraining gas supplies in Southern California, especially with storage at Aliso Canyon restricted. Together, those infrastructure failures would fuel higher energy prices across the state, ultimately costing California ratepayers at least $1 billion.

The 30-inch pipeline is still out of service, and Aliso Canyon remains restricted. Some experts are worried a heat wave could send prices soaring once again this summer.

“It’s been a mini energy crisis,” said Samuel Golding, a consultant who helps local governments launch their own power agencies.

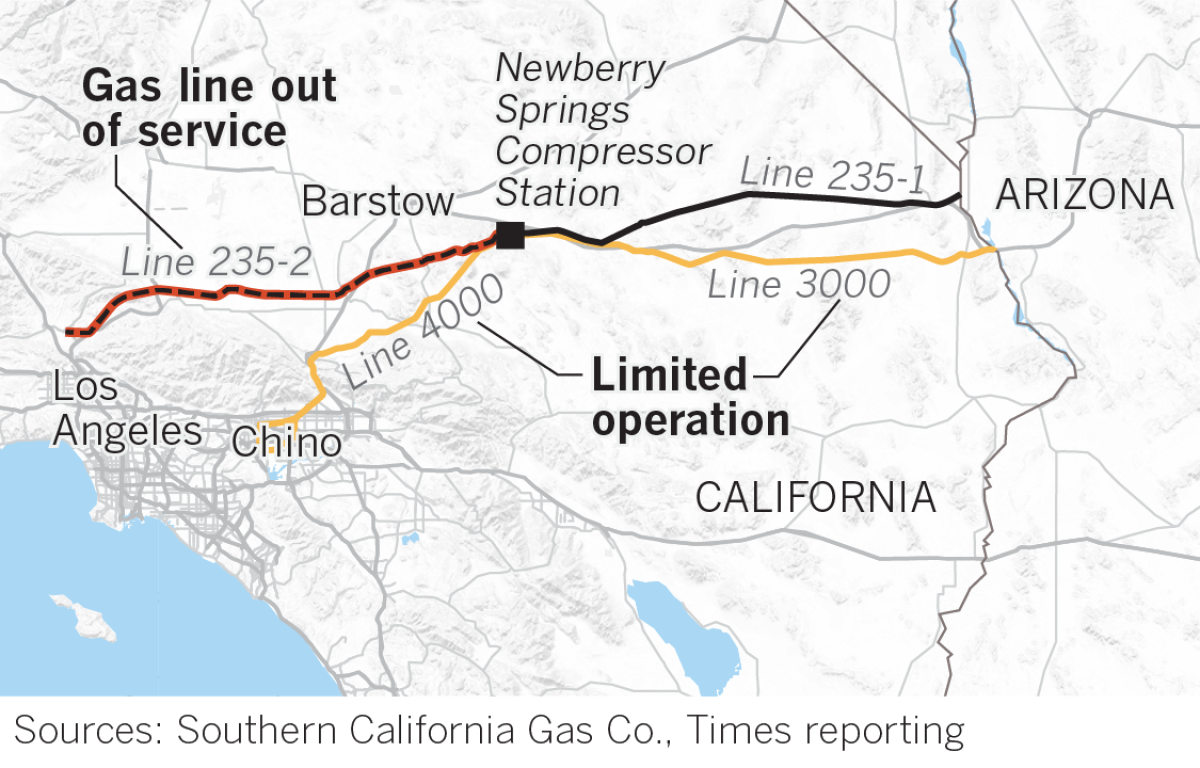

Southern California Gas originally estimated that Line 235, which was built in 1957 and carries natural gas through the desert toward the Los Angeles Basin, would return to service in April 2019. That 18-month turnaround would have been lengthy compared with recent pipeline outages in other parts of the country, which have been repaired in weeks or months.

But April came and went with no resolution.

“People have gotten married, conceived, had babies, baptized them since that pipeline has been out,” said Issam Najm, president of the Porter Ranch Neighborhood Council, at a public workshop in January.

Najm became one of the gas company’s loudest critics after the months-long Aliso Canyon blowout, which led thousands of residents of L.A.’s Porter Ranch neighborhood to flee their homes after experiencing nosebleeds, nausea and headaches, and prompted firefighters to sue SoCalGas over exposure to carcinogens. The record-setting leak followed another high-profile failure on California’s gas grid, the 2010 explosion of a Pacific Gas & Electric pipeline that killed eight people and destroyed 38 homes in San Bruno.

Clean energy advocates say those gas grid disasters — and now the extended pipeline outage — are ominous reminders that natural gas isn’t necessarily the safe, reliable and affordable fuel its promoters make it out to be. Although those advocates want to see the pipelines fixed for safety and reliability, they say California should begin phasing out natural gas by retrofitting homes and businesses with electric heat pumps and replacing gas-fired power plants with solar panels, wind turbines and batteries.

“The last thing we should be doing is throwing more and more money at the gas system that we don’t need to,” said Matt Vespa, an attorney with the environmental group Earthjustice.

The California Public Utilities Commission is concerned, too. The agency opened an investigation last month into the safety culture of SoCalGas and its parent company, San Diego-based Sempra Energy, which also owns San Diego Gas & Electric. Utilities Commission staff cited the Aliso Canyon blowout and the explosion on Line 235, writing that these incidents raise a “very serious question about whether the leadership, organizational culture and governance” at SoCalGas and Sempra prioritize safety.

What’s taking so long?

SoCalGas officials say they’ve been working diligently to restore Line 235.

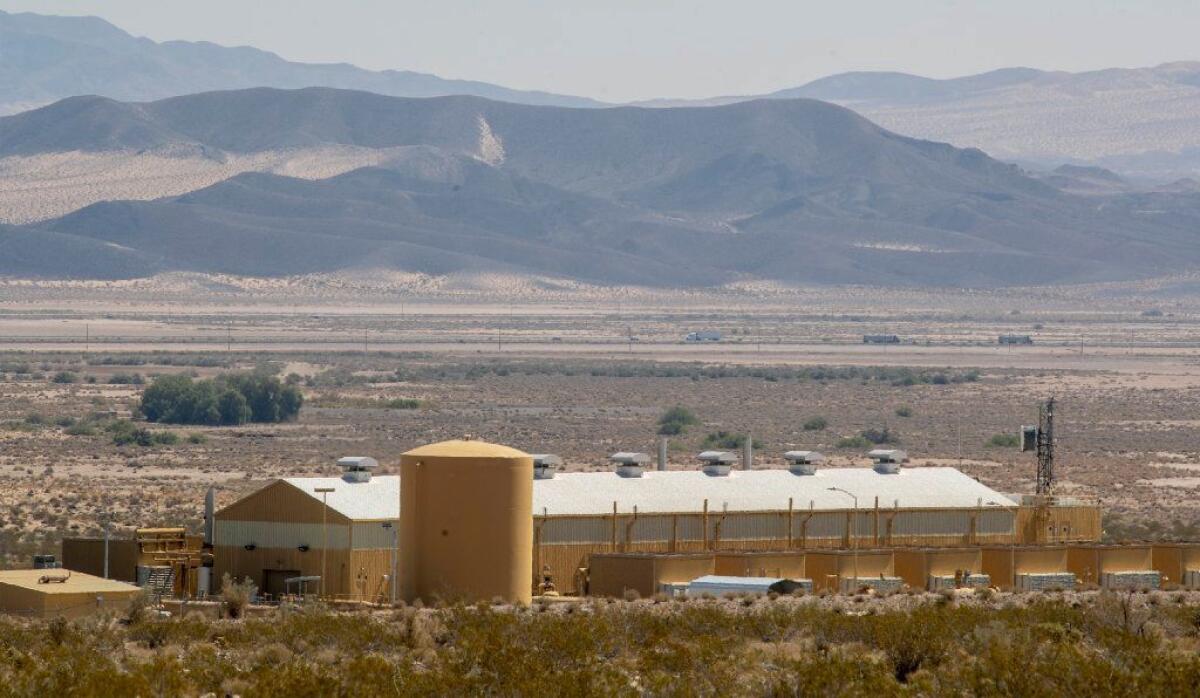

Rodger Schwecke, the company’s senior vice president for gas operations and construction, attributed the lengthy repair process to the remote desert terrain, and to environmental rules imposed by state regulators.

It’s not easy replacing several miles of buried pipe far from major population centers, where summer can bring punishing heat and winter can bring freezing temperatures and even snow. Gas company employees and contractors must drive no faster than 10 miles per hour down rough, narrow dirt roads to avoid harming desert tortoises and other at-risk species, and they must be led at all times by a biologist on the lookout for wildlife. Workers have been pulling 12-hour days, with crews on site six to seven days a week, Schwecke said.

The initial work on Line 235 was completed months ago. But SoCalGas workers have found new leaks in the pipeline every time they’ve flowed gas through it, prompting new inspections and repairs. The problems stem from corrosive desert soil, Schwecke said.

“We’re doing everything we can to make sure those pipelines come back as safe as possible,” he said.

The gas company estimates the pipeline will return to service by July 21 — assuming no more leaks are found.

But critics say SoCalGas could have moved faster.

The gas company applied for a key environmental permit from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife in July 2018 — three months after a “root cause analysis” of the pipeline’s failure was completed, and 10 months after the explosion. Then the company and state wildlife officials spent more than a month discussing the permit fee, which the state agency characterized as SoCalGas “disputing CDFW request for appropriate fees.” The parties spent another six weeks debating proposed environmental measures.

The permit was finalized in January 2019, allowing SoCalGas to work in desert streambeds.

State Sen. Henry Stern (D-Canoga Park) questioned the gas company’s actions at a hearing in March, saying the streambed permit “sat on SoCalGas’ desk signed, ready to be inked for months, and wasn’t.”

“I have significant concerns about whether or not the delays in that project repair were willful or not, and the cost to Southern California ratepayers from that delay,” Stern said.

Stern and other skeptics have wondered whether SoCalGas is purposefully slow-walking the pipeline repairs, possibly to create pressure on state officials to fully reopen Aliso Canyon. Natural gas storage at the facility has been restricted by the Public Utilities Commission since the 2015 blowout, and the commission is studying whether the facility can be shut down entirely.

The gas company has pushed back against the restrictions, saying officials could help stabilize energy prices by allowing more gas to be stored at Aliso. Oil and gas regulators at the state’s Department of Conservation have determined that Aliso could safely hold twice as much gas as is currently allowed by the Public Utilities Commission.

“Our system was built around storage assets. And when you have these pipeline outages, that just highlights the importance of storage,” Schwecke said.

Critics say SoCalGas has a financial interest in getting the storage facility up and running again.

Aliso Canyon had a net book value of $724 million at the end of 2018, according to financial filings by Sempra Energy. As long as the facility remains in operation, SoCalGas customers will ultimately be on the hook to pay off the company’s investment, plus annual profits for shareholders. Before the methane leak, SoCalGas also sold storage space to large gas users, a program that earned shareholders up to $20 million annually.

Schwecke said he’s “personally offended” by the suggestion the gas company may be slow-walking the pipeline repairs, calling the speculation “irresponsible” and “absolutely not true.” He described the environmental permitting process as relatively quick, blaming the delays in part on state wildlife officials who “wanted to expand their authority into non-streambed areas.”

He also pointed out that the gas company has proposed to permanently stop selling storage space at Aliso and other facilities to large gas users.

“We get tired of people saying we’re doing this for the money, because we’re not,” Schwecke said.

Asked about the Public Utilities Commission’s investigation into the safety culture of SoCalGas and Sempra, gas company spokeswoman Christine Detz said in an email that safety is “not just part of our culture, it is the foundation that has helped our business thrive for more than 150 years.”

Detz also rejected environmentalists’ suggestion that the gas grid is unsafe, saying that natural gas “is among the safest, most reliable and affordable forms of energy available,” and that gas infrastructure is “among the most resilient forms of energy during emergencies, including recent wildfires and earthquakes.”

Counting the costs

Line 235 exploded on Oct. 1, 2017, igniting a five-acre fire near Newberry Springs, destroying heavy equipment and damaging a nearby pipe, Line 4000. A crew of gas company employees and contractors working on Line 4000 fled before the explosion.

“If it had happened in the L.A. Basin, that would have been a San Bruno,” said Jim Caldwell, a former assistant general manager at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, referring to the deadly explosion of a PG&E gas pipeline in 2010.

SoCalGas reduced the gas flow on Line 4000 as a safety precaution, because it runs through the same corrosive desert soil as Line 235 and was built just a few years later. The company had previously stopped flowing gas through another 1950s-era desert pipeline, Line 3000, after finding external corrosion and several non-hazardous leaks. The company eventually brought Line 3000 back into service with a reduced flow.

The loss of capacity on those pipelines, layered on top of the Aliso Canyon restrictions, has rippled across the state over the last two years.

The effects were most dramatic during a heat wave last July and August, which caused homes and businesses to crank up their air conditioning. Gas prices surged to $40 per million BTU, after never exceeding $4 in 2016.

The price increases quickly spread to the electricity market, as gas-fired power plants paid more for their fuel. Those gas plants charged more for electricity, forcing electric utilities statewide to pay prices that at one point exceeded $250 per megawatt-hour, more than double the previous year’s high.

The money probably ended up in the hands of gas-fired electric generators with low operating costs, as well as gas traders who held rights to the limited capacity on the SoCalGas pipeline system, experts say.

Southern California Edison took the biggest hit, telling state regulators it spent $850 million more than expected on electricity in 2018. The company attributed a “substantial majority” of the unexpected costs to higher-than-expected natural gas prices.

Edison customers are now paying those costs through higher electric bills, as are former Edison customers who departed the utility earlier this year for Clean Power Alliance, a government-run energy provider formed by 31 city and county governments.

The Public Utilities Commission estimated that the combined effects of the Aliso Canyon restrictions and the pipeline outages cost Southern California ratepayers nearly $600 million in 2018, and Northern California ratepayers more than $300 million.

Those numbers are probably an underestimate, the commission said. And they cover only the costs to homes and businesses on the state’s main power grid, which doesn’t include Los Angeles and other cities that operate their own electrical systems.

Higher electricity prices haven’t been limited to California, said Fred Heutte, a senior policy associate at the Northwest Energy Coalition. That’s because California trades power with other Western states.

“As soon as the price spike hits on the power side, everybody across the entire West will see it. Maybe not as much, but they’ll see some effect,” Heutte said.

In the Coachella Valley, the price increases caused Palm Springs and two other cities to delay the launch of a government-run power provider called Desert Community Energy, out of concern the new agency would fall into a deep financial hole before it could build up cash reserves.

In Long Beach, which runs its own gas utility but depends on SoCalGas for delivery and storage, gas prices more than doubled during a cold snap in December. Some residents were stunned when they saw their bills.

The effects continued into February 2019, when unseasonably cold weather brought snow to Malibu and West Hollywood.

The overall cost of providing electricity on the state’s main power grid was $2.7 billion in the first quarter of 2019, according to the California Independent System Operator, up from $1.9 billion during the same period last year — a 42% increase. The grid operator said increased natural gas prices were mostly to blame, with supply restrictions in Southern California one of several factors.

‘We really have to shore up these pipelines’

Some critics say the Public Utilities Commission has moved too slowly to solve the problems on the gas grid.

Golding, who runs the consultancy Community Choice Partners, said the regulatory agency should have intervened last August, when Edison reported that its electricity costs were rising dramatically.

The commission could have limited the penalties that gas-fired power plants are charged by SoCalGas when they use more fuel than expected, which probably played a significant role in driving up gas and electricity prices, Golding said. Or the commission could have eased the restrictions on Aliso Canyon.

“Their inaction cost California billions, probably raised carbon emissions and plunged the entire Western grid into a protracted reliability emergency,” Golding said.

Ed Randolph, who leads the Public Utilities Commission’s energy division, said the agency’s staff has pushed SoCalGas to speed up work on Line 235. Earlier this month, agency staff also proposed allowing SoCalGas to withdraw fuel from Aliso Canyon more frequently, citing the pipeline outages and last year’s high energy costs. While the commission has yet to rule on that proposal, last summer it increased the amount of gas that can be stored at Aliso by nearly 40%, mentioning the continued outage on Line 235 as one of the reasons.

“We do have a huge sense of urgency around this,” Randolph said.

While greater use of Aliso Canyon could limit future price increases, some experts see the gas company’s pipelines as the underlying problem.

The huge amount of storage at Aliso “has masked infrastructure issues in the past,” said Rod Walker, a Georgia-based consultant who is studying the reliability of California’s gas grid for the state’s Energy Commission. If state officials ultimately decide to shut down the storage field — an outcome that Gov. Gavin Newsom said he was “fully committed” to during last year’s campaign for governor — it will become even more important for SoCalGas to operate the rest of its system safely and reliably, Walker said.

“We really have to shore up these pipelines,” Walker said.

SoCalGas will bring Line 235 back into service with reduced gas flow while the company develops long-term plans for its ailing desert pipes. And once Line 235 is back, the company plans to shut down and run tests on Line 4000, which has also experienced leaks related to external corrosion. That means gas supply constraints similar to last summer’s could continue for months.

Even with pipeline capacity still limited, experts say it’s hard to predict if electricity prices will skyrocket again this summer. There are too many variables, including weather and energy demand, not just in California but in other Western states.

One factor that might help: Above-average snowpack across much of the West means there should be plenty of cheap hydropower available as temperatures rise. The Public Utilities Commission also recently approved a proposal from Edison to cap the penalties that gas-fired power plants pay to SoCalGas when they use more fuel than expected.

Although SoCalGas is skeptical the penalty cap will help, Edison estimates the change would save ratepayers at least $200 million under conditions similar to last summer.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.