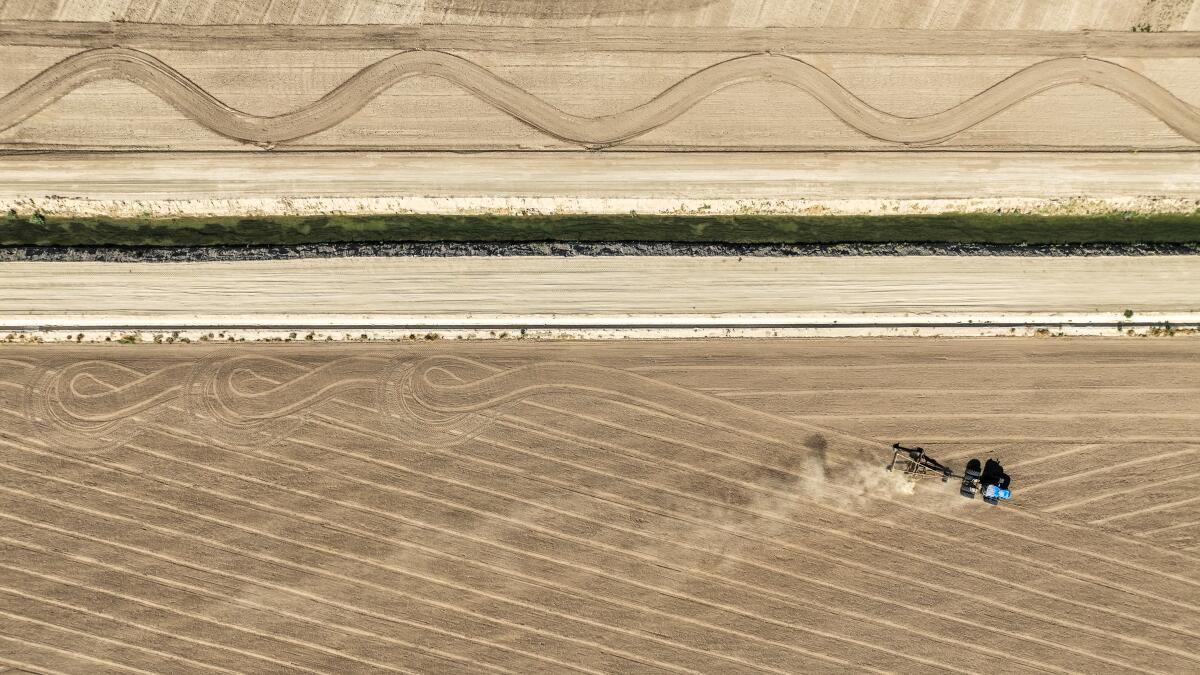

California farmers set to cut use of Colorado River water, temporarily leaving fields dry

Welcome to Boiling Point. I’m Ian James, a reporter on The Times’ climate team, writing the newsletter this week to fill in for my colleague Sammy Roth.

Farmers who grow hay in the Imperial Valley will soon be eligible to receive cash payments in exchange for temporarily shutting off water to their fields for up to two months this year.

Under a program approved by the board of the Imperial Irrigation District, farmers can now apply for federal funds to compensate them for harvesting less hay as part of an effort to ease strains on the Colorado River.

Paying growers to leave fields dry and fallow for part of the year represents a major new step by the district to help boost the levels of the river’s reservoirs, which have been depleted by chronic overuse, years of drought and higher temperatures caused by climate change.

The Imperial Irrigation District delivers the single largest share of the Colorado River’s water to farmlands that produce hay for cattle as well as many of the country’s vegetables. District officials developed the so-called deficit irrigation program based on input from growers. They say the approach is aimed at avoiding longer-term fallowing of crops that would take farmland out of production and bring a heavier blow to food production and the area’s economy.

Tina Shields, the district’s water manager, called it a “mini-fallowing program.”

“The goal is to strengthen the Colorado River and ensure long-term viability and reliability,” Shields said. “It’s our only water supply. And we also want to keep ag in production, because that’s the bread and butter of our local economy. And we think that there’s ways to do both.”

The district’s board last week approved the plan to pay farmers $300 per acre-foot of water they forgo during a 45-day or 60-day period starting in August.

Those growing alfalfa or two other types of hay — Bermuda grass or klein grass — are eligible. Those three crops, as of mid-June, were being grown on 234,000 acres in the valley, according to district data, and accounted for nearly three-fourths of the area’s 320,000 acres of cultivated farmland.

The district is still awaiting environmental approvals to begin the program. Once it starts, officials plan to lock canal gates and shut off water to the fields of participating farmers.

Shields estimates that the district, which last year delivered about 2.4 million acre-feet of water, might be able to conserve roughly 200,000 acre-feet this year. (As part of a deal to reduce water use in California, Arizona and Nevada, the Imperial Irrigation District has pledged to conserve a total of 700,000 acre-feet through 2026.)

The new conservation program focuses largely on alfalfa because it can be harvested eight or nine times a year, and even after a month or two without water, the plants can recover when irrigation is restored. Growers who volunteer to participate will give up one or two cuttings, but can then resume farming.

Federal money for the program is set to come from funds that Congress approved as part of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022.

The Imperial board also voted last week to increase the amount that farmers can receive through the district’s existing “on-farm” conservation program, which pays those who invest in converting flood-irrigated fields to water-saving systems such as sprinklers or drip irrigation. Through that program, growers will now be able to receive $430 per acre-foot of water conserved.

The district’s goal is to help address the Colorado River’s shortage while avoiding long-term fallowing, “the evil F-word here in our community,” Shields said.

Farmers in the Imperial Valley enjoy water rights that date to the early 1900s, when settlers diverted water from the Colorado River to make the desert bloom. Many farmers say they understand the water shortfall will require significant cutbacks throughout the Southwest, but hope to avoid measures that would harm the economy or shrink food production.

The seasonal fallowing program is designed, Shields said, to keep fields in production, “target specific crops where we think we can get some significant water savings, and minimize the impacts on the local community.”

The Colorado River provides water to seven states from Wyoming to Southern California, as well as 30 tribes and northern Mexico. The river has long been overallocated, and reservoir levels have dropped dramatically as hotter, drier conditions have reduced flows over the last 25 years.

The river’s condition has improved somewhat with wetter winters since 2023. But Lake Mead, the country’s largest reservoir, remains just 33% full, while the second-largest reservoir, Lake Powell, is now at 42% of capacity.

Throughout the Colorado River Basin, water management officials have been looking to the Imperial Irrigation District to play a pivotal role in efforts to adapt because the Imperial Valley uses more water than Arizona and Nevada combined. Last year, the district accounted for 65% of the total usage of Colorado River water in Southern California.

The district has significantly scaled back water use over the last two decades. Under a 2003 water transfer deal, it has been selling a portion of its water to Southern California cities.

Throughout the Southwest, conservation efforts have significantly reduced demands on the Colorado River in California, Arizona and Nevada in recent years. According to a recent federal report, the three states’ combined Colorado River water usage last year was the lowest since 1983.

Still, the low water levels of Lake Mead and the projections of continuing declines driven by global warming have led to widespread agreement that additional cutbacks will be needed to prevent the river’s reservoirs from reaching critically low levels.

“As we’re looking forward to a drier future, it’s going to take everyone to contribute,” said JB Hamby, the Imperial Irrigation District’s vice chair and California’s Colorado River commissioner.

“I think what is notable about what IID has been doing through this effort has been clearing all kinds of hurdles to be able to make that conservation happen,” Hamby said. “I think if everyone took that same sort of mind-set, that will certainly position us well throughout the basin to confront the river’s future challenges.”

To start the new conservation program, the district will first need to approve a funding agreement with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

Shields said the district is also awaiting environmental reviews and will need approval from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. She said wildlife officials want to make sure that reductions in water use wouldn’t shrink the flows of irrigation runoff in drains near the Salton Sea to a point that would affect endangered desert pupfish or a bird species, the Yuma Ridgway’s rail.

As the region’s water managers have discussed solutions for the Colorado River’s water deficit, many have looked to the large amount of water dedicated to growing water-intensive hay crops. In one recent study, researchers found that alfalfa and other hay crops consume 46% of the water that is diverted from the river. Much of the hay goes to feed cattle for beef and dairies, while some types are grown for horses.

Increasing amounts of hay have also been exported in recent years to countries such as China and Saudi Arabia.

In other agricultural areas of Southern California, such as the Palo Verde Irrigation District in Blythe, farmers have already been participating in programs that pay them to leave some fields dry. But growers in the Imperial Valley haven’t followed suit until now.

“We want to do our part to ensure that our resource is maintained in future years,” said Scott Emanuelli, who represents more than 500 farmers as president of the Imperial County Farm Bureau.

He said the goal is to rebuild reservoir levels and have a sustainable river system “so that we can have a future in farming, so we continue to feed the world.”

Growers in the valley want to continue investing in more efficient water use and would prefer to avoid any fallowing of land, Emanuelli said. The temporary seasonal fallowing program, he said, is “a compromise we’ve had to meet in order to help prop up the river.”

Farmers have until Tuesday to apply to take part in the program. Emanuelli said he and his family, like many other growers, are weighing pros and cons to decide whether the program will work for their businesses.

He said factors that will probably lead more growers to sign up include relatively low hay prices as well as high operating costs. Emanuelli said he and others still expect that the downturn in farm output means the valley’s businesses will “take a hit.”

This is the latest edition of Boiling Point, an email newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. You can sign up for Boiling Point here. And for more climate and environment news, follow @Sammy_Roth and @ByIanJames on X.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.