Would an occasional blackout help solve climate change?

This story was originally published in Boiling Point, a newsletter about climate change and the environment. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

What’s more important: Keeping the lights on 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, or solving the climate crisis?

That is in many ways a terrible question, for reasons I’ll discuss shortly.

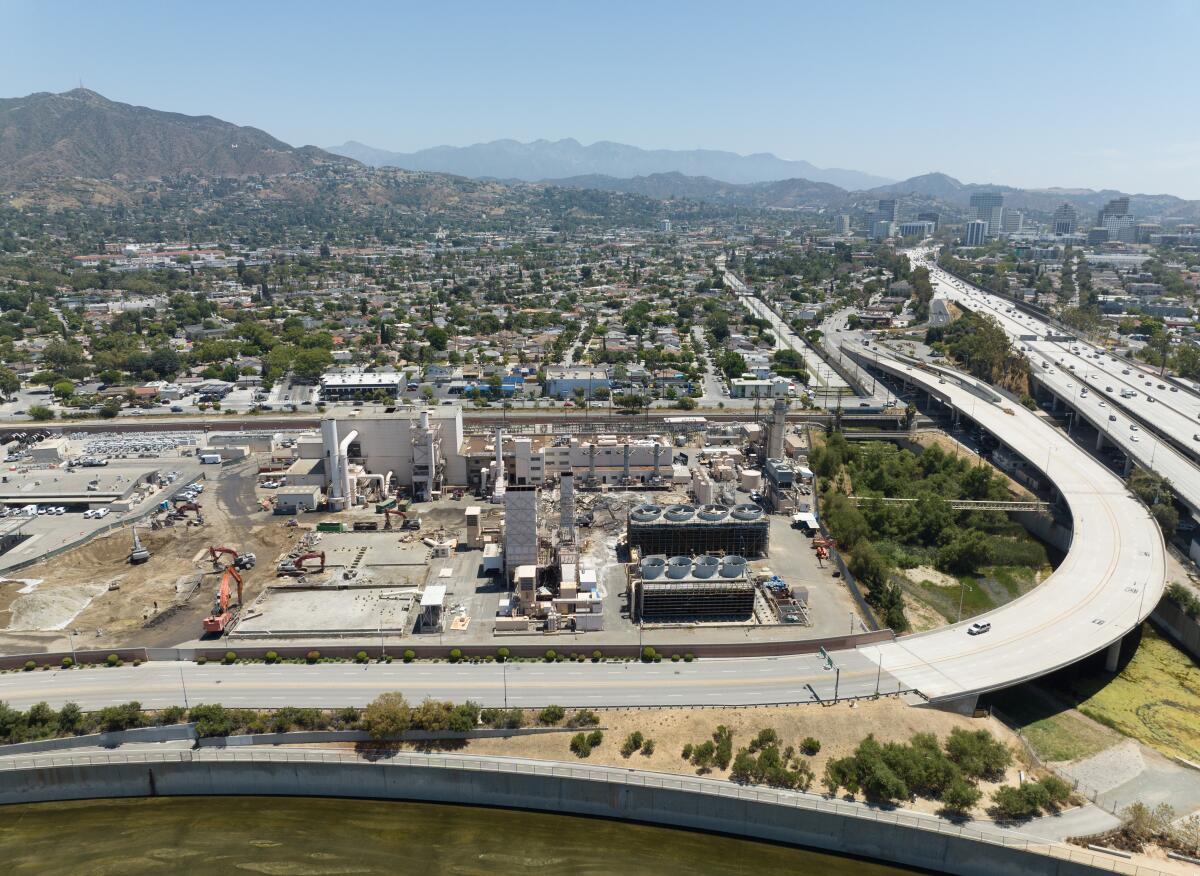

But it’s been on my mind as a ferocious heat wave roasts California and other states — and as I’ve watched Glendale respond to a Sierra Club lawsuit over the fate of the city’s gas-fired power plant, just across the L.A. River from Griffith Park.

I sat in a dimly lit courtroom in downtown Los Angeles last week as the lawyers squared off. An attorney representing the Sierra Club argued that Glendale officials had exaggerated the need for the gas plant as they urged the City Council to spend an estimated $170 million to keep burning fossil fuels. An attorney for the city countered that the investment — which the council approved in a 4-1 vote — is desperately needed to provide reliable electricity to Glendale’s roughly 190,000 residents, and avoid blackouts.

It’s a highly technical dispute. But it’s part of a larger conversation about how much blackout risk we consider acceptable in modern society — and whether our expectations should evolve in the name of preventing climate catastrophe.

That conversation kicked into high gear in August 2020, when California found itself short on electricity during a heat wave. Just under half a million homes and businesses lost power for as little as 15 minutes and as long as 2½ hours on a Friday evening, when high temperatures kept Californians blasting their air conditioners even as the sun went down and solar farms stopped producing power. The following evening, another 321,000 utility customers went dark for anywhere from eight to 90 minutes.

The rolling outages were short and contained, relatively speaking. But the political reaction was swift and dramatic.

Gov. Gavin Newsom — facing a recall effort and wanting to avoid the fate of his predecessor Gray Davis, who was voted out of office after an energy crisis — suspended air-quality rules to make it easier to run polluting backup generators. The next summer, Newsom issued a similar order preemptively allowing gas plants to exceed air-pollution limits during electric-grid emergencies.

The governor took his biggest swing at reliable electricity in June 2022, persuading state lawmakers to pass a controversial bill directing billions of dollars toward emergency energy supplies — including lots of money for planet-warming fossil fuels.

The Golden State has avoided additional power shortages — but not without some close calls.

Two years ago this month, California narrowly avoided rolling outages after wildfire smoke knocked out electric lines that carry large amounts of power from the Pacific Northwest. The state again toed the precipice during a hot spell last September, fending off blackouts only after officials sent out an emergency alert to millions of mobile phones begging people to use less power.

Again and again, I’ve found myself asking: Would it be easier and less expensive to limit climate change — and its deadly combination of worsening heat, fire and drought and flood — if we were willing to live with the occasional blackout?

I’m not talking about a long-term future of sketchy power supplies. Plenty of studies have found that keeping the lights on with 100% climate-friendly electricity is entirely possible, especially if energy storage technologies continue to improve.

But our short- and medium-term futures are more tricky.

Solar panels and wind turbines produce some of the cheapest electricity on the market, and lithium-ion batteries that can store solar power for a few hours after sundown have fallen in cost. But building out those clean-power facilities can take a long time, especially given recent supply-chain delays — even with financial support from President Biden’s climate law.

Gas plants, meanwhile, supplied 42% of California’s electricity last year, according to a federal tally. And in a great irony of the climate era, increasingly extreme weather driven by fossil fuels has made those gas plants more valuable than ever.

But absent major breakthroughs in carbon-capture technology, we’ll eventually need to shutter most if not all of those gas plants to avoid disastrous temperature jumps. Scientists say we need to cut carbon pollution nearly in half by 2030.

Could we get started ditching gas sooner — and save some money — by accepting a few more blackouts for the next few years?

It’s a heretical question in power-grid circles. When I posed it to John Moura — director of reliability assessment and performance analysis at the North American Electric Reliability Corp. — he only half-jokingly described it as “a dagger to the heart.”

I got a similar reaction on Twitter.

Of the hundreds of people who responded to my question, most rejected the idea that more power outages are even remotely acceptable — for reasons beyond mere convenience. A former member of the L.A. Department of Water and Power’s board of commissioners wrote that “someone dies every time we have a power outage.” An environment reporter in Phoenix — where temperatures have exceeded 110 degrees for a record 20 straight days — said simply, “Yikes.”

Moura expanded on his skepticism by noting that modern life is more reliant on electricity than ever before.

Those of us lucky enough to have air conditioning depend on it to stay safe during heat waves — which can already kill thousands of people and are only getting more dangerous as fossil fuels warm the planet. Elderly people and individuals with certain health conditions are more vulnerable to heat illness and sometimes need electricity to power their medical equipment, such as ventilators, dialysis machines and motorized wheelchairs. Our refrigerators, cellphones and internet service all depend on reliable electricity.

“It’s not really about keeping the lights on. It’s about keeping people alive,” Moura said.

There’s another compelling argument for taking aggressive steps to avoid even a slight uptick in outages: Americans really hate blackouts. And faced with more of them, even people concerned about climate change might turn against clean energy.

The idea that solar farms and wind turbines will never supply reliable electricity has become a popular right-wing talking point. Even when fossil-fuel infrastructure fails during extreme weather, Republican politicians typically blame solar and wind.

Those fossil fuel-funded lies shouldn’t inform our decision-making. But they contain a kernel of truth, which is that the U.S. power grid isn’t yet capable of running entirely on climate-friendly electricity 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Does that mean we should be willing to accept even a few more hours of blackouts, if it means burning less gas?

When I posed my dagger-to-the-heart question to Mark Rothleder — chief operating officer at the California Independent System Operator, which oversees the state’s main electric grid — he responded that spurring power outages by shutting down gas plants too soon “will potentially undermine the [clean energy] transformation, because the public will no longer be on board.”

“They didn’t sign up for a clean, affordable, less reliable grid,” he said. “They signed up for a clean, reliable and affordable grid.”

On balance, I think Rothleder and Moura are right. We should do everything we can as a society to add solar panels, wind turbines and all kinds of energy storage to the grid as fast as possible. To the extent those additions allow the closure of fossil-fueled power plants, awesome — the sooner the better. But closing them too soon could bring its own kind of disaster.

After reporting on clean energy for most of the last decade, I’ve increasingly come to the conclusion that solving climate change will require sacrifices — even if only small ones — for the sake of the greater good. Those might include lifestyle changes such as driving less or eating less meat. They might also include accepting that large-scale solar farms will destroy some wildlife habitat, and that rooftop solar panels — despite their higher costs — have an important role to play in cleaning up the grid.

Maybe learning to live with more power outages shouldn’t be one of those sacrifices.

But at the same time, we might not have a choice.

The power grid is already prone to blackouts caused by events as small and difficult to avoid as a squirrel chewing on an electric line, said Emily Grubert, a civil engineer and environmental sociologist at the University of Notre Dame. And as we enter “a pretty long period of climate dynamism,” she told me, guaranteeing reliable electricity supplies will only get harder.

Already, the grid has been battered by more powerful storms, more intense wildfires and more extreme heat.

The idea of accepting a less dependable electric grid “is uncomfortable for a lot of people, because they correctly point out you may end up in situations where the wealthier you are, the more you’re able to buy your way out of that reliability problem,” Grubert said. Think rooftop solar panels paired with a battery in the garage, or a backup diesel generator.

That’s why it’s crucial, Grubert said, for government to be ready to protect society’s most vulnerable when it’s hot and the power goes out. That could include investing in a wider network of cooling centers, with transportation to help people get there.

“There are conversations to be had about how you fail gracefully,” Grubert said.

The less we fail, the better. But Grubert thinks there could be additional benefits from planning for failure. The better we are at keeping people safe during blackouts, for instance, the easier it would be to figure out if there are cheaper, faster paths to 100% climate-friendly energy — even if those paths involve a slightly higher tolerance for blackout risk than we have today.

Is it realistic to think that shifting our expectations for “reliability” could help us tackle the climate crisis?

“It’s worth checking,” Grubert said. “We haven’t really gone through that exercise yet.”

All of which brings us back to Glendale, with its gas plant along the banks of the L.A. River.

Even before last week’s court hearing, the judge in the Sierra Club’s lawsuit had issued a tentative ruling — yet to be finalized — in the city’s favor. The Sierra Club, the judge tentatively concluded, had failed to prove its case that Glendale officials issued an incomplete environmental analysis before City Council voted to spend hundreds of millions of dollars “repowering” the Grayson gas plant with a combination of new, less-polluting gas engines and lithium-ion batteries.

After spending a few minutes at last week’s hearing questioning the attorneys about the need for the gas plant, the judge spent a lot more time considering the merits of a separate lawsuit filed by a group of locals who say Glendale officials failed to consult with the city’s Historic Preservation Commission before approving the destruction of the Grayson plant’s boiler building — which a lawyer for the group described as “magnificent” and “historic.”

Setting aside the question of whether we should preserve old energy infrastructure because some people appreciate the architecture, I’m sympathetic to both sides of the debate. That includes Byron Chan, an attorney with the nonprofit law firm Earthjustice, who responded to Glendale’s case for less-polluting gas engines by telling the judge that “just because it makes the air cleaner, it doesn’t mean the air is clean” for communities surrounding the Grayson plant.

It also includes Mark Young, general manager of Glendale Water & Power, who told me in an interview that avoiding outages is wildly complicated — and that the city has committed to running the new gas engines at just 14% of their annual capacity.

“It’s not that Mark Young wants to screw over the environment,” Young said. “There’s rational thought behind it.”

There’s also room for common ground as we navigate these thorny debates.

Nearly everyone I interviewed for this story, for instance, highlighted the value of “flexible demand” programs that shift electricity use away from the highest demand times. Families comfortable with 81-degree indoor temperatures, for instance, could get paid to turn up the thermostat a few degrees on the hottest evenings. People with electric cars could be incentivized to charge at a lower cost overnight. Big factories could be required to cut back during stressful moments on the grid.

Eric Hittinger, a public policy professor at Rochester Institute of Technology, said those types of programs could allow gas plants to fire up a lot less — even if we keep some of them around a few more decades to help during the hottest heat spells.

“I would love to be in a place where our main concern was that 5% or 10% of our electricity comes from natural gas, and how would we phase that out?” he said. “If we get to that point, we’re really close to winning the whole energy transition.”

Indeed, solving climate change isn’t as simple as replacing gas and coal plants with solar and wind farms. We need to get tens of millions of electric vehicles on the road, and tens of millions of electric heat pumps in people’s homes. We also need to build a lot more long-distance power lines to move renewable electricity from where it’s generated to where it’s needed.

The more we electrify society, the fiercer the debates will become over whether to shut down our remaining gas plants. And the debates are already pretty fierce — not just in Glendale, but also in Huntington Beach, Los Angeles and elsewhere.

Fortunately, California doesn’t appear to be at much risk of power shortages during this week’s heat wave. It helps that the state now has 5,600 megawatts of battery storage on its main power grid, up from 500 megawatts three years ago.

But the story of climate change is just getting started — as is, hopefully, the story of clean energy.

ONE MORE THING

One way California and other Western states could do a better job keeping the lights on — while continuing to cut down on fossil fuel combustion, and potentially saving billions of dollars — would be to share more electricity across state lines.

At least, there are many clean energy advocates who think so. And their push for a coordinated Western electric grid — in which California could more easily tap into low-cost wind power from Wyoming, for instance — got a boost late last week, when state officials from Arizona, California, New Mexico, Oregon and Washington announced a new effort to create an independent agency to govern electricity markets across the region. The nine signatories included two appointees of Gov. Gavin Newsom.

“We are committed to the vision of maximizing the benefits of organized wholesale electricity markets,” they wrote.

The regional market concept has its skeptics, including some consumer advocates, environmentalists and labor unions, as I’ve written previously. Critics within California have said the state shouldn’t cede control of its energy system to a regional body that might be more likely to favor fossil fuels — or pursue policies that would result in solar and wind construction jobs going out of state. There’s also lingering distrust of electricity markets following the Enron-led market-manipulation fiasco of the early 2000s.

But the idea hasn’t gone away, and neither have its supporters. I’ll keep following this one.

We’ll be back in your inbox Tuesday. To view this newsletter in your Web browser, click here. And for more climate and environment news, follow @Sammy_Roth on Twitter.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.