Newsletter: Climate change will get worse in 2022. But it won’t be the end

This is the Dec. 30, 2021, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

What is there to say about 2021 that hasn’t already been said?

Heat-trapping carbon dioxide kept piling up in the atmosphere, peaking at 419 parts per million, up from 280 parts per million before the Industrial Revolution. Hundreds of people died from extreme heat in the Pacific Northwest as several states suffered their hottest summers on record; infernos burned 2.6 million acres in yet another unprecedented wildfire season for California; drought emptied reservoirs and prompted a first-ever shortage declaration on the Colorado River. An oil spill marred the Pacific coast.

And the pandemic continued to rage, despite the existence of highly effective vaccines that might have stopped COVID-19 in its tracks, or at least made the virus easier to manage. Misinformation and fear-mongering kept far too many people from protecting themselves and their loved ones, in much the same way that climate denial and delay slowed the transition to cleaner energy.

I wish I could tell you that 2022 will bring anything much different, but I doubt it. Even with record-breaking snowfall this month in parts of California — which may not bring the drought to an end but should at least alleviate it — I’m expecting next year’s top stories to look a lot like this year’s. Prepare for deadly heat waves, brutal wildfires and occasional COVID-19 surges, accompanied by a surge of lies that will make your blood boil with disbelief but will nonetheless be believed by a great many Americans.

Here’s the thing, though — about climate and coronavirus both.

In April 2020, when the L.A. Times launched this newsletter, stay-at-home orders were still in effect, and vaccines were a distant dream. The federal government vacillated between treating climate change as a minor inconvenience and as a hoax. Clean energy technologies such as solar panels and batteries were more expensive than they are now, and toilet paper was in short supply.

If I had my choice between living in April 2020 and January 2022, it wouldn’t be a difficult decision.

Yes, Congress hasn’t been able to pass President Biden’s climate bill — and there’s plenty to criticize in the Biden administration’s climate performance thus far. Meanwhile, vaccines appear to be less effective against Omicron than against earlier variants.

But as easy as it is to live and die with each day’s news — with every disappointing headline, frustrating tweet and panicked proclamation by the talking head on your TV screen — the story of climate change is long, as is the story of the pandemic. Both crises were decades in the making. Neither will be resolved anytime soon, certainly not by the end of 2022.

The best we can hope for is incremental progress — two steps forward, one step back, a string of little victories that slowly add up to something more. As the climate journalist David Roberts wrote recently, global warming “remains stubbornly uncathartic.”

“There will be no final moment of recognition and no clear line between success and failure,” he wrote. “The result will be an unsatisfying muddle at every stage, with more suffering than there should have been but less than there could have been.”

So yes, the world is in bad shape right now, and it will be in bad shape next year. But it was in bad shape before 2021, too. And here we are still forging ahead, celebrating good news when it comes and hopefully remembering to find joy in the people and experiences that make life worth living. Whatever happens next — scary as it may be in the moment — it won’t be the end.

So good riddance to the unsatisfying muddle that was 2021, and a toast to the muddle that will be 2022.

For the last time this year, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

A newly protected “home on the eco-range” for wildlife in the Tehachapi Mountains north of L.A. helps link together the Sierra Nevada, San Joaquin Valley grasslands, the Mojave Desert and the Baja Peninsula. If you want some hope heading into the New Year, read this story by my colleague Louis Sahagún about the Nature Conservancy’s Randall Nature Preserve, which protects creatures such as mountain lions and bobcats from pressures including urban sprawl, climate change and wind farms.

In the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers — where agriculture is thought to have begun — climate-fueled drought and upstream diversions by Iran and Turkey are drying up some of the world’s most fertile farmland in modern-day Iraq. Here’s the fascinating story by our Middle East bureau chief, Nabih Bulos, with photos by our globe-trotting photographer Marcus Yam. It’s a reminder that the human tragedies wrought by climate change also have the potential to fuel geopolitical conflict.

There’s a crazy amount of snow in the Sierra Nevada right now. Donner Pass has seen more than 250% (!) of its average snowfall since the start of the water year, with 210 inches (!!) making December the area’s third-snowiest month on record, as my colleagues Hayley Smith and Melody Gutierrez report. One Sierra resident described it as “snowmaggedon.” Many highways were shut down, with Lake Tahoe cut off from the rest of California, Hayley reports. Check out these wild images compiled by our photo department, as well as Francine Orr’s gorgeous pictures of Yosemite National Park blanketed in snow. Here in the Southland, meanwhile, intense rain has been wreaking havoc, with evacuation warnings in wildfire burn zones and cars getting swept up in swelling rivers. This is all good for water supply, but the drought is far from over. And as the Sacramento Bee’s Ryan Sabalow and Phillip Reese note, one upstate reservoir is actually releasing water to protect against downstream flooding in Sacramento.

WATER IN THE WEST

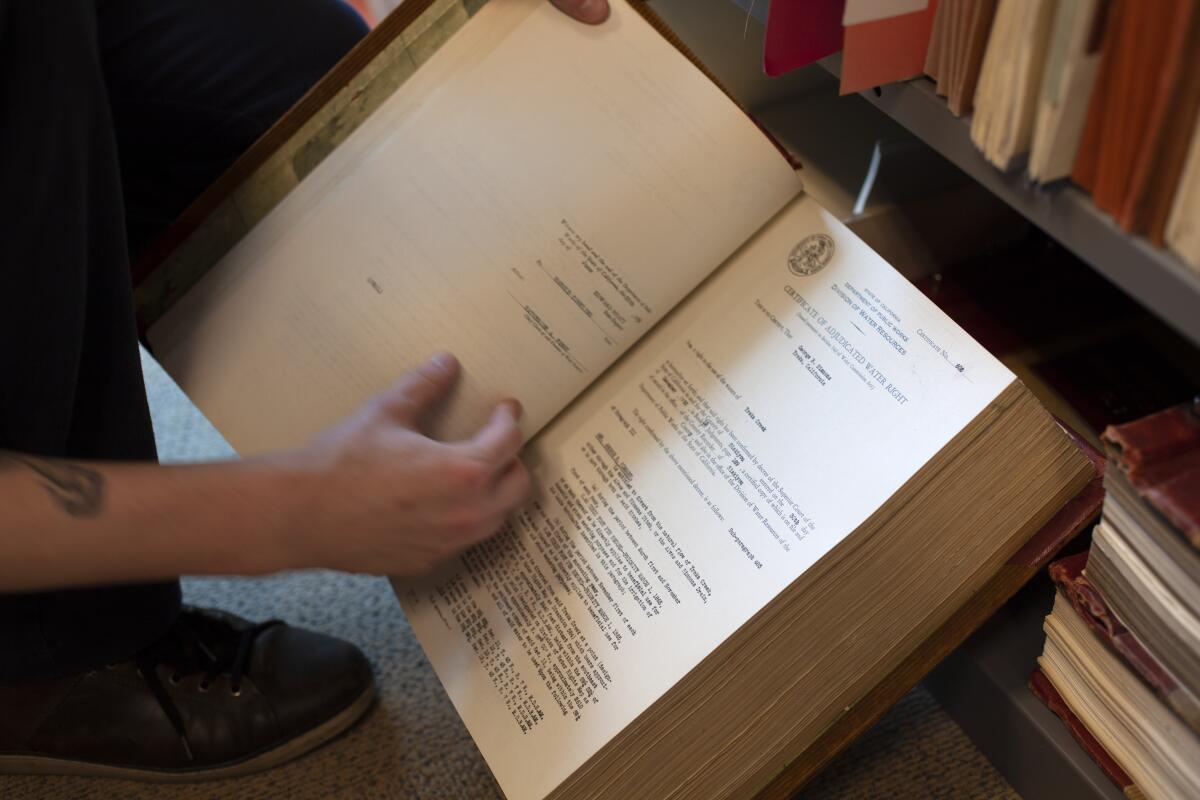

There’s a room with millions of pieces of paper documenting more than a century of California water rights, and it’s so heavy that the floor had to be reinforced. Yes, that’s right, the birthplace of the computer age keeps track of its most precious resource using filing cabinets crammed with pages that can be as delicate as tissue paper. The state has finally commissioned a digital records system, Ari Plachta reports for The Times, which should allow for more reliable enforcement of water limitations.

“Without the tribes, there’s no deal.” My colleagues Ian James and Jaweed Kaleem wrote about the key role played by Native American nations in the latest Colorado River negotiation, which ended with California, Arizona and Nevada agreeing to leave more water in Lake Mead. Looking ahead, tribes might help end a history of “exploitation, extraction and development at all costs” on the Colorado, to quote one Indigenous elder. Meanwhile, the recent federal infrastructure bill includes $2.5 billion to help bring long-promised water to tribal nations, including from the Colorado, the AP’s Suman Naishadham and Felicia Fonseca report.

The Associated Press asked sports teams in the Colorado River Basin with grass or ice playing surfaces what they’re doing to conserve water. The Arizona Diamondbacks ripped out grass at Chase Field and replaced it with artificial turf, but overall, reporter Erica Hunzinger found that most teams aren’t doing anything transformative. Professional sports are a drop in the bucket of overall water use and climate pollution, but they have an opportunity to set a strong example for society, as I wrote last month.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

Santa Monica will offer affordable housing to Black families displaced by construction of the 10 Freeway. The city has fewer Black residents today than it did in 1960, in part due to the decision to bulldoze the Pico neighborhood, my colleague Liam Dillon reports; it’s one of many examples of low-income communities and people of color being shoved aside for highways, as Liam and Ben Posted recently chronicled in a powerful investigation. In related news, a judge ruled against a Westside group that was trying to stop L.A. from building 6,000 apartments and condos within half a mile of Expo Line transit stations, per City News Service.

In a 3-2 vote, the West Basin Municipal Water District killed a desalination plant in El Segundo it had been considering building for 20 years, after deciding it doesn’t actually need the water. Environmentalists concerned about harm to marine life celebrated the decision, Kristy Hutchings reports for the Daily Breeze; a separate desalination plant that Poseidon Water hopes to build in Huntington Beach is still alive. In other coastal news, there was yet another oil sheen in the water off Orange County, The Times’ Priscella Vega reports. Unlike October’s major oil spill, this one was caused by the small Oxnard-based company DCOR.

What do you need to know about California’s new law requiring everyone to compost their food waste? My colleague James Rainey has a comprehensive explainer that spells out what’s expected of you, whether you live in a house or an apartment. The law takes effect Jan. 1 but will be phased in over the next few years, so cities and counties don’t have to worry about fines just yet.

AROUND THE WEST

Photojournalist Jay Calderon started taking pictures of the Salton Sea in 1999, giving him a front-row seat as the desert lake became an ecological disaster. “The changes are happening so quickly now, it’s a shock.... But as my photos show, the sea isn’t dead,” Jay writes for the Desert Sun, introducing an online exhibit showcasing his photography. Check out Jay’s photos of fish die-offs and migratory birds, captured by wading through mud or floating down the Whitewater River; of geothermal power plants and lithium extraction; of dust-control efforts that create “ugly and dead-looking landscapes”; and of decaying structures along the former shoreline. See also these mind-bending before-and-after photos, showing how some spots have changed dramatically.

“In a sense, the Forest Service is the nation’s largest water company.” Most of Utah’s water comes from forest snowpack, but state and federal officials aren’t tracking how much water is diverted from forests or even reviewing expired permits, Joan Meiners reports in a thorough investigation for the St. George Spectrum & Daily News. This story is the latest entry in a USA Today Network series on the Forest Service’s failure to protect Western water supplies, even though that’s supposed to be part of its mission.

Global warming and coastal development threaten the sunflower sea star, which lives in tidal and sub-tidal areas along the West Coast. The Biden administration is considering protecting the sea star under the Endangered Species Act — and if it does, California might have to modify its plans for sea walls and other barriers against sea level rise, Bobby Magill reports for Bloomberg Law. Elsewhere in the West, federal officials say the 6-inch cactus ferruginous pygmy owl — which nests in saguaro cacti in Mexico, Arizona and Texas — should be protected under the Endangered Species Act, Michael Doyle reports for E&E news.

ONE MORE THING

I wrote this summer about a surprising obstacle to America’s biggest wind farm: the Biden administration. A federal agency was helping to block construction of a 730-mile transmission line designed to carry power from a 3,000-megawatt Wyoming wind farm toward the West Coast, in a fascinating example of the growing tension between conservation and fighting climate change.

Now the conflict has been resolved. An energy company owned by the billionaire Phil Anschutz — who is developing both the wind farm and the TransWest Express power line — sent me a settlement signed last week, in which Colorado’s Cross Mountain Ranch and federal officials agreed to allow construction. The U.S. Department of Agriculture had previously funded a “conservation easement” on the Colorado property, which supporters said would protect sage grouse habitat and a wildlife migration corridor.

The settlement will also allow construction of a power line developed by PacifiCorp, an arm of Warren Buffett’s energy empire.

ACTUALLY, JUST ONE MORE THING

Harry Reid died this week. The longtime Nevada politician not only got President Obama’s Affordable Care Act passed as Senate Majority Leader but also played an influential role in Western environmental issues, helping to establish Great Basin National Park and protect millions of acres of wilderness, killing coal plants and the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste facility, and brokering deals to settle water disputes while allowing the Las Vegas Valley to keep growing — a controversial tradeoff in the nation’s driest state.

Reid grew up in a hardscrabble mining town called Searchlight, a few miles from the Colorado River but a world away from the lights of the Strip. I passed through a few years ago and was so enchanted by the local history museum that I bought a copy of Reid’s book, “Searchlight: The Camp That Didn’t Fail.” I finally started reading it this week, because it’s never too late.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.