How a federal agency is blocking America’s largest wind farm

This is the Aug. 5, 2021, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Way back in 2019, I asked an energy company owned by one of America’s richest individuals to alert me when they were down to one final landowner standing in the way of their plan to send massive amounts of wind power from Wyoming to California.

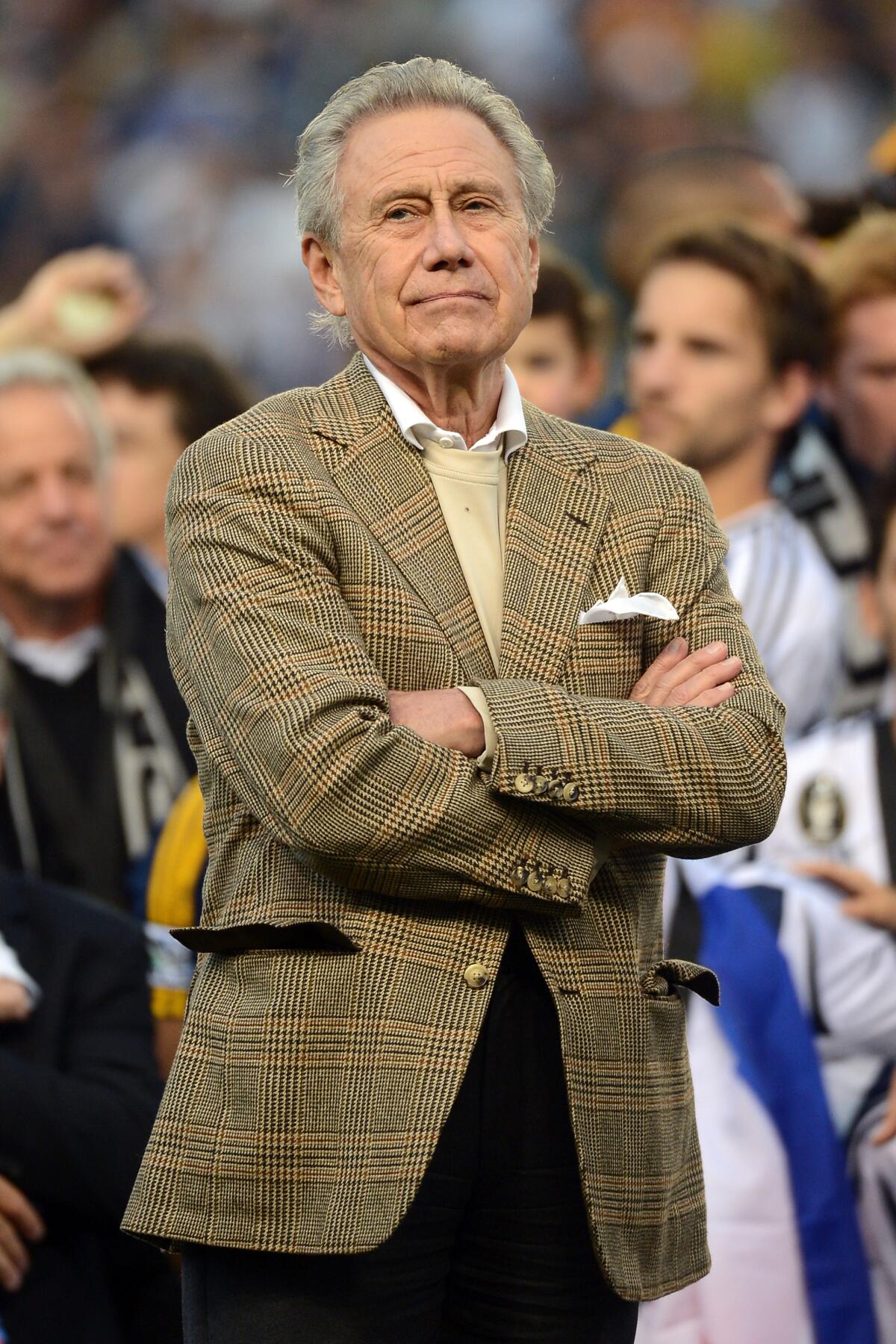

It had been a dozen years since Phil Anschutz first proposed to build the country’s largest wind farm, as well as a 730-mile transmission line to ferry the clean electricity toward the West Coast. Federal officials had signed off on the power-line route, but Anschutz Corp. still needed to work out financial arrangements with hundreds of private landowners whose properties the towers and wires would cross. I was interested in writing about the final holdout along the route, if the project got that far.

This week, company officials finally had an answer for me. They said the last landowner standing between California and an infusion of climate-friendly power will be a family of Colorado ranchers — working closely with a federal agency.

That’s right: Even as President Biden urges Congress to fund a rapid buildout of clean energy infrastructure to fight climate change, an arm of his administration is helping to block the country’s largest renewable power project.

It’s a conflict that illustrates the difficulty of quickly transitioning away from fossil fuels, especially given the opposition to solar farms, wind turbines and transmission lines that has bubbled up in communities across the West. That opposition is motivated at times by aesthetic concerns and at times by a desire to protect animals and ecosystems from industrial energy development.

Let’s back up a minute.

Anschutz got rich drilling for oil in the Intermountain West decades ago. Today he owns or holds major stakes in the Los Angeles Lakers, L.A.’s Staples Center and the Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival. Forbes estimates his net worth at $10.1 billion.

Since 2008, Anschutz Corp. has spent more than $400 million permitting and preparing to build 1,000 wind turbines on a giant ranch in south-central Wyoming, as well as hundreds of miles of electric wires that would cross through Colorado, Utah and Nevada, ending near Las Vegas. As I’ve written previously, the wind in Wyoming peaks in the afternoon and stays strong into the evening, meaning it could help California keep the lights on after sundown — a challenge recently, as you may have heard.

It sounds like an easy win for California, Wyoming and our planet’s climate. But here’s where things get complicated.

A small handful of landowners are still haggling with Anschutz Corp. over how much they ought to be paid to allow TransWest Express to cross their properties. The company tells me it expects to be able to resolve its issues with every landowner except one: Cross Mountain Ranch, an enormous sheep and cattle operation in northwest Colorado.

Under normal circumstances, Anschutz Corp. might try to invoke eminent domain. But several years ago, the Natural Resources Conservation Service — an agency within the federal Department of Agriculture — spent $3.3 million to help fund a “conservation easement” across 16,000 acres of Cross Mountain Ranch. In exchange for that money, the landowning Boeddeker family agreed not to sell any of the ranch to a developer who might build homes (or anything else). Power lines wouldn’t be allowed.

Conservation easements are meant to preserve rural economies dependent on agriculture, while also protecting farm and ranch lands that provide wildlife habitat. At Cross Mountain Ranch, federal officials said an easement would support the greater sage grouse, an iconic Western bird whose sagebrush habitat has been decimated by residential and industrial development.

“This became quickly one of the highest-priority sage grouse initiative projects in the country, because of the size, the connectivity to the public lands,” said Erik Glenn, executive director of the Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust, which helped broker the Cross Mountain Ranch easement. “It’s a pretty pivotal migration corridor for mule deer, for elk... You’re frequently going to see sandhill cranes along the Yampa and Little Snake rivers in their migration periods.”

Anschutz’s TransWest subsidiary sued the Department of Agriculture in 2019, arguing that the Natural Resources Conservation Service violated federal law and its own policies when it approved and funded an easement that would block the planned power line. The company wants a judge to throw out the easement. Department of Agriculture officials have countered that they followed the law and were totally in the right to prioritize conservation, regardless of how it might affect the energy project.

Here’s the key point: Regardless of who wins in court, this battle illustrates a tension that is only getting more pressing as America hurries to confront the fires and floods of the climate crisis.

I’m referring to the tension between building renewable energy infrastructure and protecting ecosystems, which I’ve written about extensively. President Biden wants the United States to get 100% of its electricity from climate-friendly power sources by 2035. He’s also endorsed a campaign by scientists and advocates to protect 30% of America’s lands and waters by 2030.

There are ways to meet both of those goals, and they most likely involve carefully studying which landscapes ought to be fully protected and which can be set aside for development. But those strategies won’t resolve every conflict. There will always be difficult value judgments about the appropriate balance between conservation and fighting climate change.

For Anschutz Corp., the facts on the ground at Cross Mountain Ranch clearly weigh in favor of climate. The company points out that its transmission-line corridor would take up just 30 acres of the 16,000-acre conservation easement, and would allow for the delivery of enough wind energy — 3,000 megawatts — to power nearly two million homes.

U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack — who served in that role under President Obama, and now again under Biden — has actually praised TransWest Express, along with six other power lines selected by the Obama administration for accelerated permitting a decade ago. Vilsack said the projects would “help to meet our country’s electric needs in the 21st century.”

“These infrastructure projects will also create jobs and opportunities that will strengthen our economy to benefit households and businesses throughout the country,” Vilsack said in a written statement in 2011.

I asked TransWest’s general counsel, Lisa Christian, about one arm of the Biden administration blocking a power line meant to help Western states ditch fossil fuels while most of the rest of the federal government pushes aggressive climate action. She was perplexed, to say the least, telling me the company has “tried repeatedly” to get Biden administration higher-ups to step in.

I also asked Glenn, from the Colorado land trust, whether sacrificing 30 acres out of 16,000 for a power line would really be that big a deal. He pointed me to research suggesting transmission infrastructure can harm sage grouse.

“We’ve got a policy priority of increased renewable energy, and we have a policy priority of increased conservation. Those two are going to continue to butt heads,” he said. “We have to find ways to resolve those conflicts.”

I also reached out to the owners of Cross Mountain Ranch. A 2017 Denver Post story described the property — which had been put on the market at the time, although it hasn’t sold — as “the rural family compound of the late Ronald Boeddeker, the Southern California real estate tycoon renowned for luxury developments like Lake Las Vegas and Waikoloa Beach Resort in Hawaii.”

Boeddeker’s son Matt didn’t respond to my interview requests. But he definitely opposes a transmission line. In a 2019 email cited by TransWest’s lawsuit, he wrote to a Natural Resources Conservation Service official that his family “agreed to permanently restrict (from development and for the protection of important wildlife) a very large part of one of the largest private ranches in Colorado in exchange for the govts part in full protection against power lines and other damaging items of development.”

“It’s impossible for this power line to happen if you take actions,” he wrote.

It’s hard for me to say if TransWest Express and the accompanying wind farm would really be canceled if the company’s lawsuit fails. Anschutz has spent hundreds of millions of dollars and a dozen years on these projects, and construction is still at a very early stage. I wouldn’t be surprised if he were willing to throw some more money and time at trying to reroute the power line.

I should note that the Department of Agriculture didn’t grant an interview request. After this story was published, the department’s press secretary, Kate Waters, told me via email that the Natural Resources Conservation Service “believes there is a path forward to resolve this issue in a way that works for all parties” and “will continue to seek common ground.”

I should also note that another company owned by one of America’s wealthiest individuals — the electric utility PacifiCorp, a subsidiary of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway empire — also wants to build a transmission line, known as Gateway South, along the same route through Cross Mountain Ranch as Anschutz. PacifiCorp has its own legal action pending over the conflict.

But that’s a story for another day. For now, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

California’s deadliest wildfire displaced tens of thousands — not just in Paradise, but in poorer, more isolated mountain towns. Three years after the Camp fire, many are still living in the woods with their kids or searching for a safe place to park their RVs as they desperately wait on a payout from Pacific Gas & Electric, my colleague Joe Mozingo writes in this heart-wrenching story, with photos by Gina Ferazzi. In related news, PG&E may have started not one, but both blazes that merged to become the Dixie fire, which is burning through the same region as the Camp fire, J.D. Morris reports for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Before they were flattened to make way for houses and beachgoers, huge rolling sand dunes covered much of California’s coastline, supporting an incredible array of bugs, plants and birds. Restoring some of those “living shorelines” could help protect us against rising seas, according to this beautifully illustrated story by The Times’ Rosanna Xia, Paul Duginski and Sean Greene. It’s a remarkable piece of journalism that will make you rethink everything you thought you knew about the beach.

“Then there were the cattle, thousands of them, some so skinny they looked like skeletons.” We published two powerful stories this week about how climate-fueled drought is decimating farming communities. The first takes place in the Mexican state of Sonora, where reporter Kate Linthicum and photographer Gary Coronado found that tens of thousands of cows are starving to death, threatening to bring an end to the ranching way of life. The second takes place in Arizona, where reporter Jaweed Kaleem and photographer Carolyn Cole talked with family farmers and ranchers who may be forced to sell out as water supplies dry up.

DROUGHT AND FIRES

How bad is the drought in California? It’s so bad that state officials just barred thousands of people, mostly farmers, from pulling water from rivers and streams in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Watershed. Here’s the story from The Times’ Julia Wick, who notes that officials want to make sure there’s enough freshwater available to flow into the Delta next year to keep salty ocean water away from the pumps that supply much of the state with drinking water. Meanwhile, Rachel Schnalzer writes that visitors to Folsom Lake can now see the remains of Gold Rush towns because water levels at the reservoir have fallen so low.

The U.S. Forest Service will stop letting small fires burn in overgrown forests, at least temporarily, saying there’s too big a risk they’ll become out-of-control infernos. More details here from my colleagues Anita Chabria and Lila Seidman. Putting out all fires as quickly as possible may sound obvious, but letting some burn through dense forest underbrush is to meant improve forest health after decades of over-suppressing fire, in hopes of preventing larger future blazes. But the practice has faced criticism from Western politicians, including Gov. Gavin Newsom, as Anita and Alex Wigglesworth reported just a few days ago.

Newsom is also urging President Biden to continue a program that gives firefighters access to images from military satellites. The governor raised the issue just days after The Times’ Jennifer Haberkorn and Anna M. Phillips reported that the Pentagon might let the FireGuard program expire, despite the fact that it has likely saved lives by allowing for faster evacuations.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

Even before the Western drought took a turn for the worse in 2021, hydropower plummeted in California. New data show that generation from in-state hydroelectric facilities was down 44% last year, Rob Nikolewski reports for the San Diego Union-Tribune. Partly as a result, California burned more natural gas, which unlike hydropower fuels climate change. Less water behind hydropower dams is one of several reasons the state could face rolling blackouts in the coming weeks. (For more discussion of the water-energy nexus, see this event hosted by Circle of Blue and the Pacific Institute that I participated in on Wednesday.)

A new law signed by Oregon Gov. Kate Brown requires the state’s largest electric utilities to slash climate pollution 80% by 2030, 90% by 2035 and 100% by 2040. That’s five years ahead of California’s target of 100% clean energy by 2045, if you’re keeping score at home; more details here from the AP’s Sara Cline. Similarly, some clean energy advocates say Colorado now has the strongest policies for reducing climate pollution from gas heating in buildings, Allen Best writes for Energy News Network.

A new book offers a sweeping history of Tesla, largely focused on the smart people not named Elon Musk who helped build the electric car company. My colleague Russ Mitchell wrote a review of “Power Play” by Tim Higgins, and he understandably couldn’t help but lead with a juicy anecdote from the book about Tim Cook floating the idea of Apple buying Tesla.

Record heat. Raging fires. What are the solutions?

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter about climate change, the environment and building a more sustainable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

AND EVERYTHING ELSE

L.A.’s Hyperion sewage treatment plant kept releasing millions of gallons of partially treated wastewater into the ocean weeks after a major spill, in violation of its environmental permit. The Times’ Robert J. Lopez broke this story just one day after public health officials suggested high bacteria levels at beaches probably had nothing to do with the sewage spill because more than two weeks had passed. Officials say water quality has now returned to state standards, Melissa Hernandez reports.

Deadly floods in recent weeks have made clear that China’s Henan province is not prepared for increasingly extreme weather. But rather than engage in a public conservation about climate change, “the ruling Communist Party has restricted information and encouraged nationalistic celebration,” writes The Times’ Beijing bureau chief, Alice Su. Our Middle East bureau chief Nabih Bulos, meanwhile, reports with Omid Khazani that Tehran is slowly sinking due to over-extraction of groundwater, while water and power shortages have sparked protests in another part of Iran where temperatures often reach 123 degrees.

Bringing things back to the U.S., last week was Drought Week on The Times, our daily podcast hosted by Gustavo Arellano. Episode 1 featured our in-house “masters of disasters”; Episode 2 focused on water shortages and right-wing extremism; Episode 3 dealt with the Southwest’s iconic plants, from Joshua trees and saguaro cactuses to, yes, lawns; Episode 4 was all about falling water levels at the West’s largest reservoir, Lake Mead; and Episode 5 somehow brought together drought impacts to carne asada and to our smartphones. I’d highly recommend you subscribe to the podcast and make Gustavo part of your daily routine.

ONE MORE THING

I lived in Palm Springs for four years, so it caught my attention that the city just had its hottest July on record, per the Desert Sun’s Tom Coulter — right after its hottest June on record. Jonathan P. Thompson, who writes the Land Desk newsletter, notes that there were 392 all-time high temperatures records tied or broken in the United States in June — all of them west of the Mississippi.

Here at The Times, our photographers documented what the heat looked like and how we coped. But this is one of those strange scenarios where even a great picture doesn’t contain enough multitudes to tell the whole story. The West is getting hotter and drier and more fire-prone, and the only way to fully understand it is to live through it. Which we’re all doing, as best we can.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week with more plum content. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.