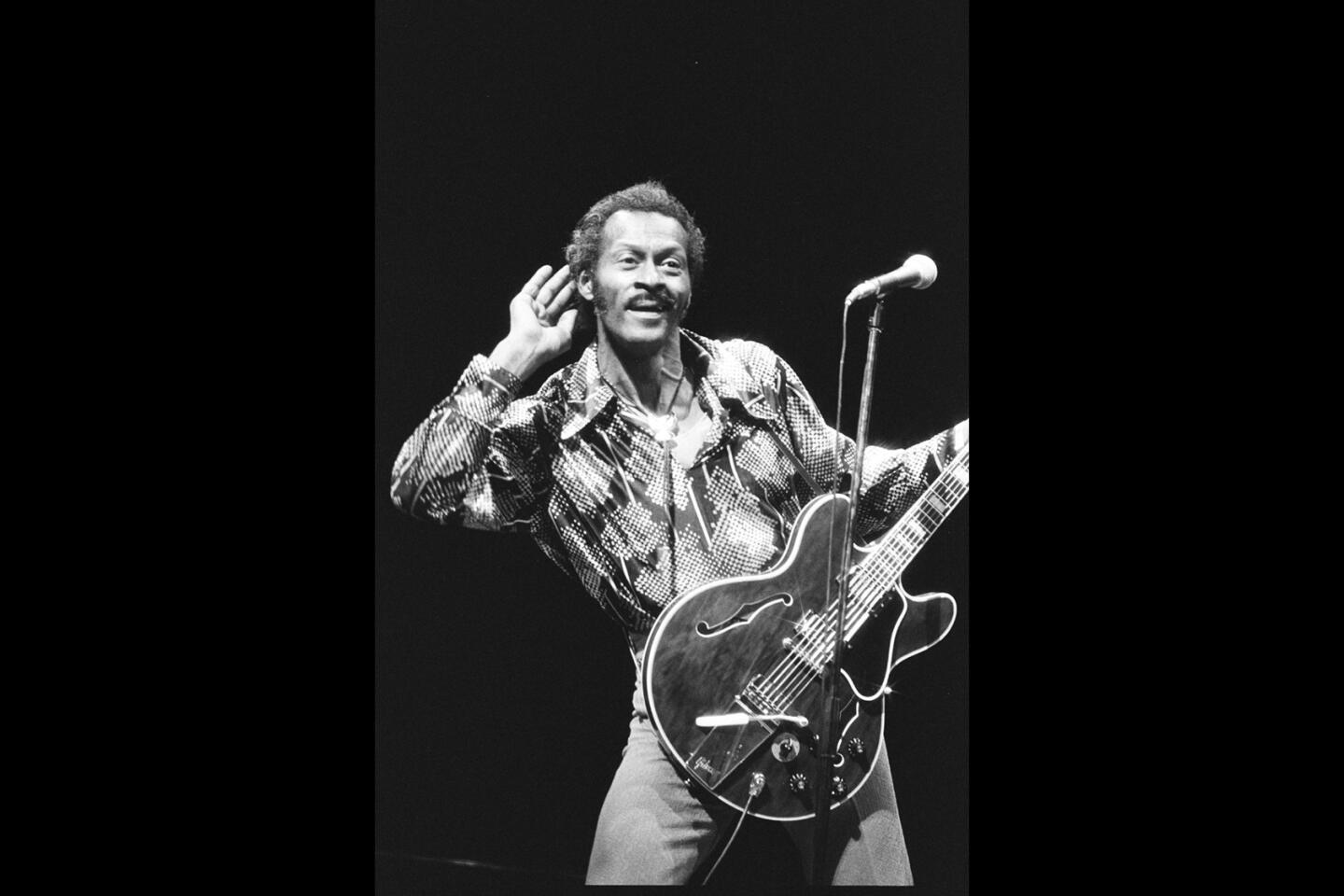

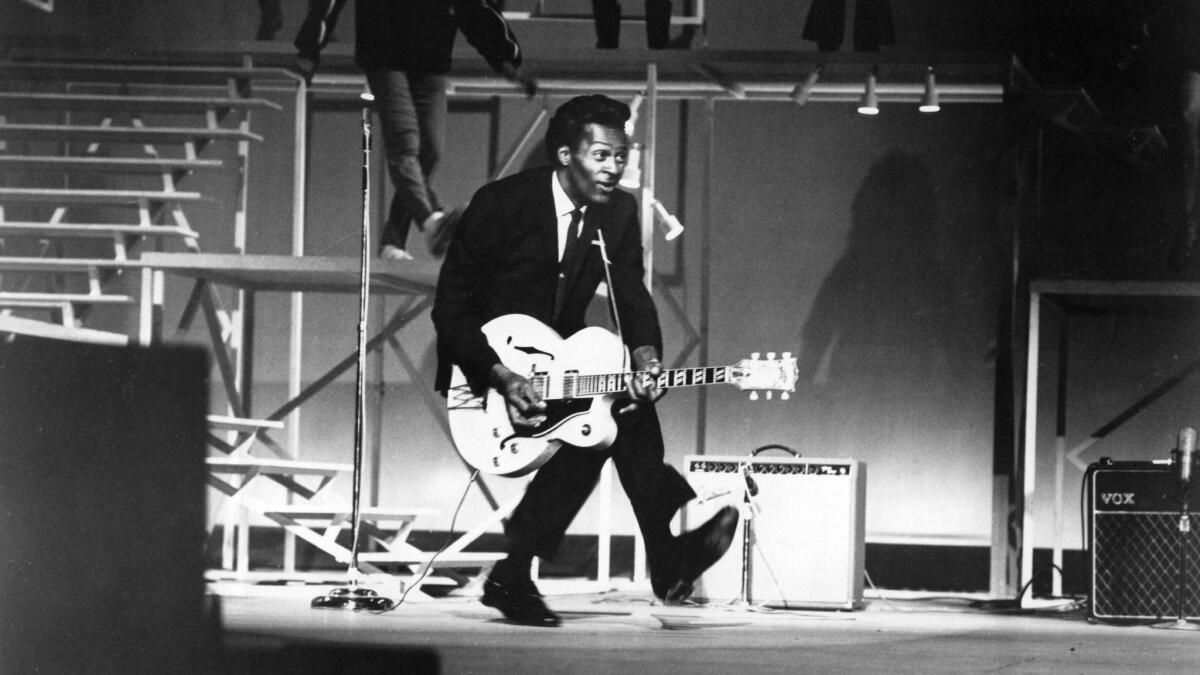

Chuck Berry was a master of detail whose music defined a genre

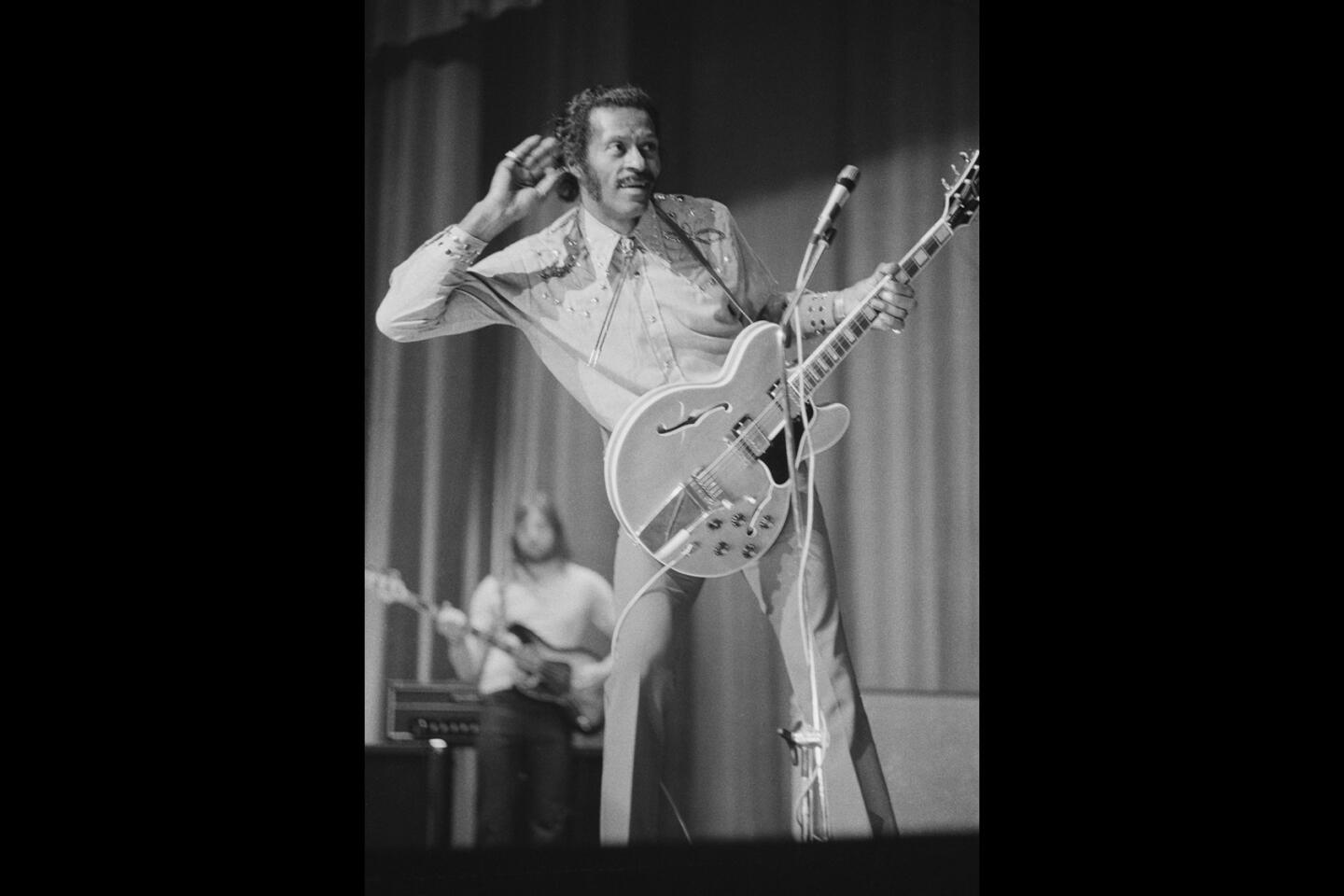

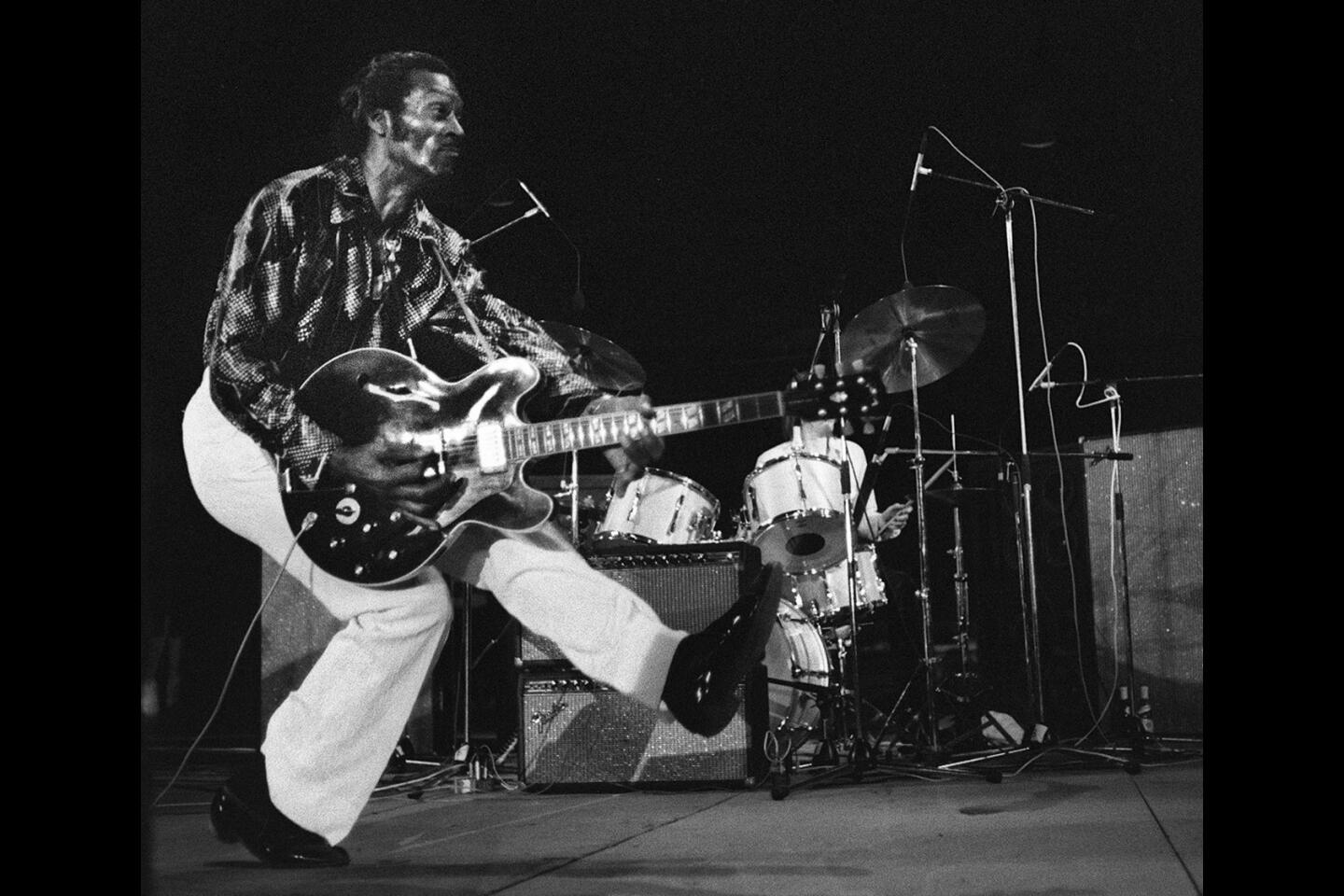

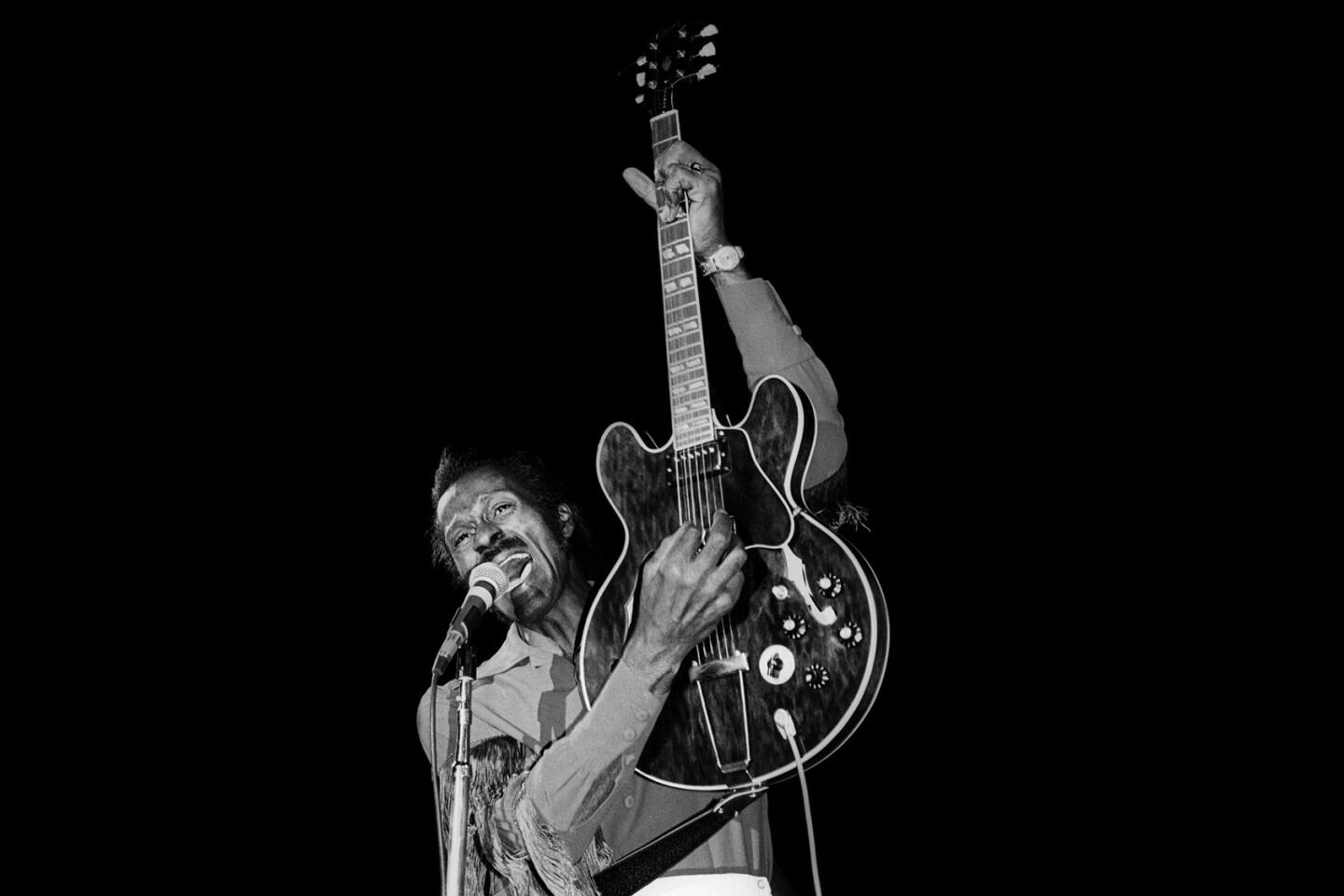

In the later years of his career as a live performer, Chuck Berry famously toured by himself, opting to play with local musicians hired to back him for individual gigs rather than traveling with (and paying the salaries of) his own band.

The idea this could suggest was that Berry’s music was easy to play — that it was so generic that any promoter in any town could find a couple of guys to handle bass and drums while Berry held the crowd’s attention on vocals and guitar. (The practice also suggests that Berry wasn’t interested in spending money he didn’t have to spend.)

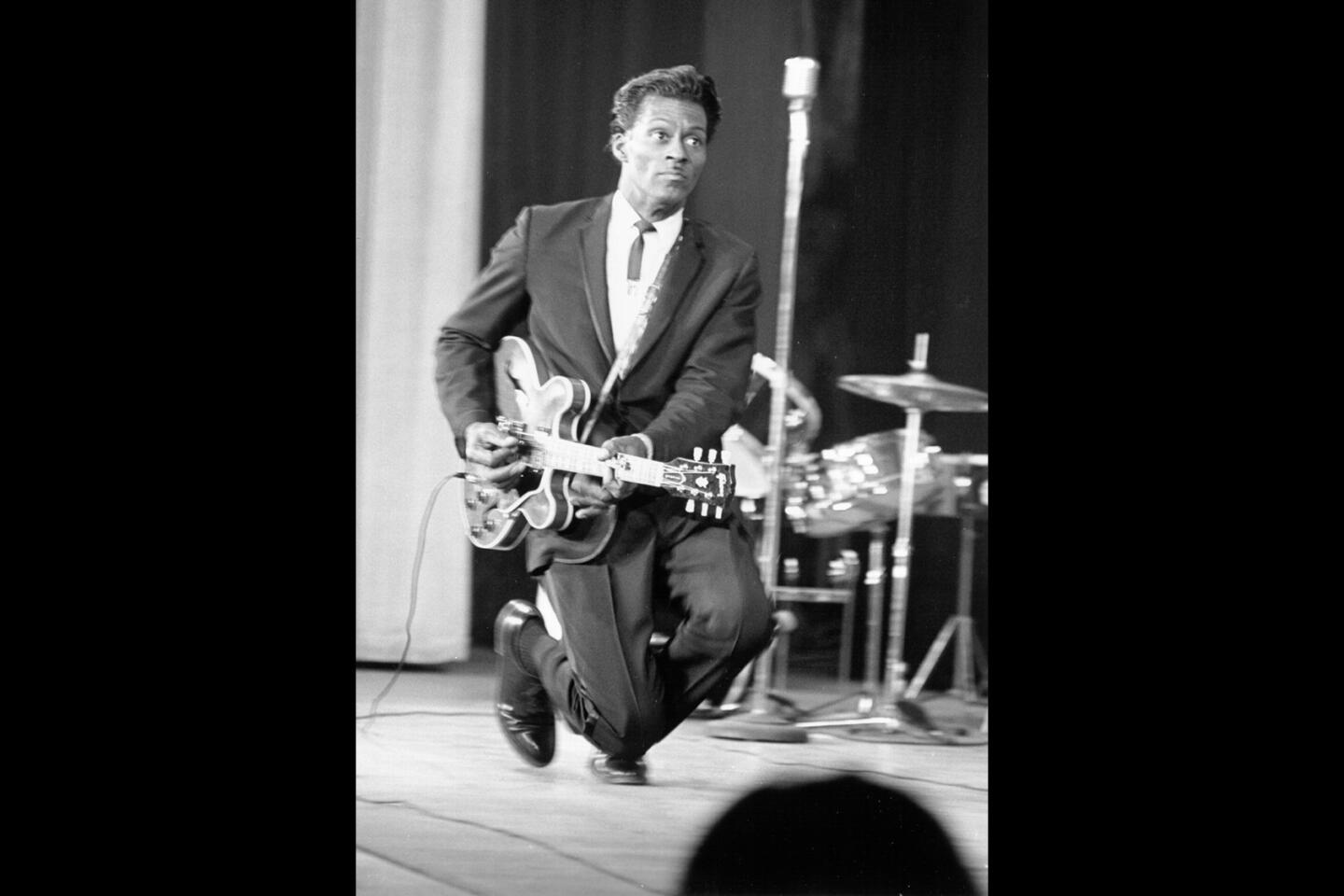

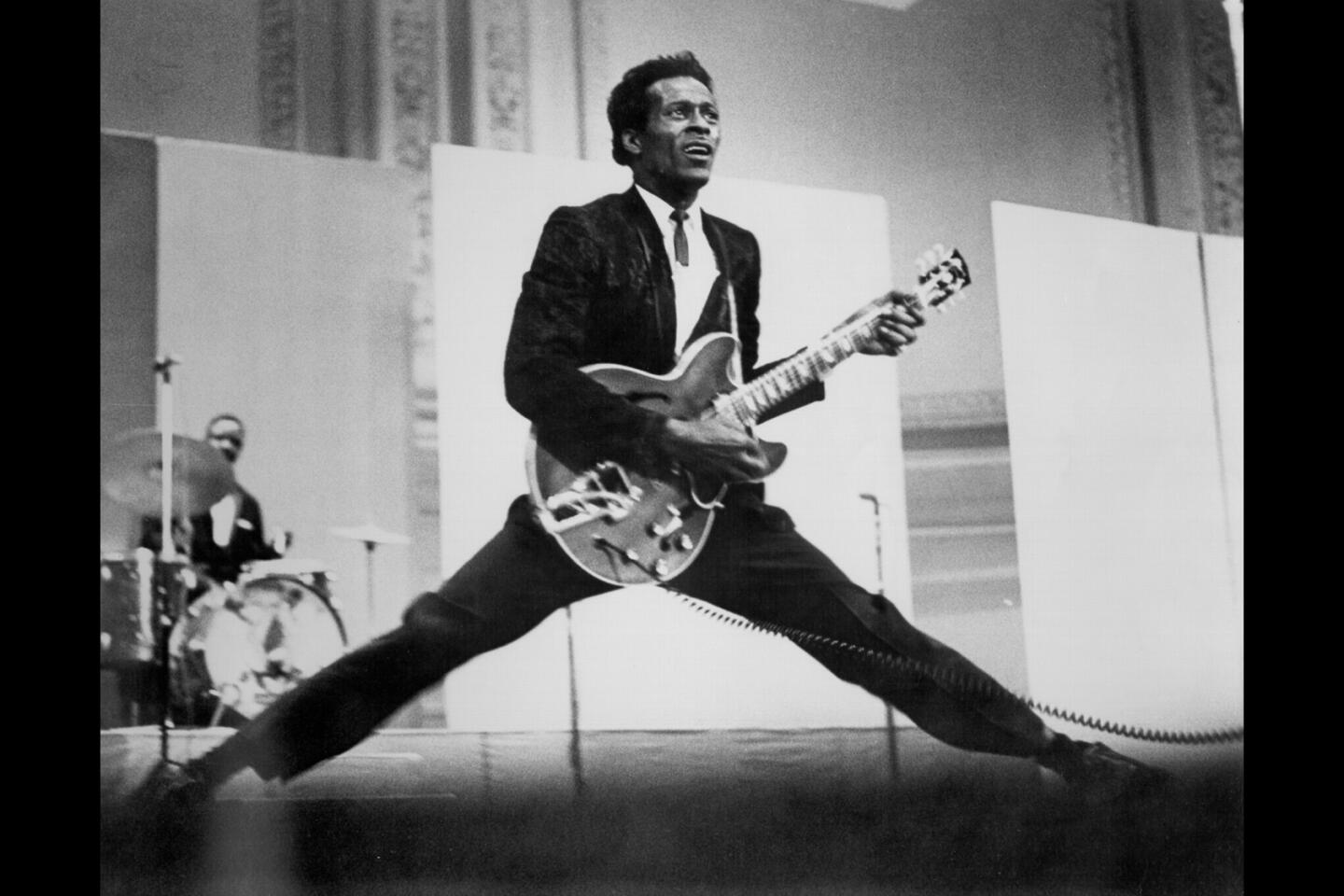

And, in a sense, that idea is not far off: Berry, who died Saturday at his home near St. Louis at age 90, basically invented rock ’n’ roll with songs from the mid- and late 1950s such as“Maybellene,” “Roll Over Beethoven” and “Johnny B. Goode,” each an audacious yet crafty blend of riff, melody, rhythm and attitude.

So of course Berry’s music soon came to seem elementary. It defined a genre, one that grew quickly after his example thanks to acolytes such as the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and the Beach Boys.

To think of Berry’s work as simple, though — as vague or without detail — is to profoundly misunderstand the compositions and classic recordings that made him a star.

Take “Maybellene,” his very first single, which he based on an old country tune but tricked out with an indelible guitar lick and his own invented word: “As I was motor-vatin’ over the hill / I saw Maybellene in a Coupe de Ville,” he sings, creating a vivid image of newness even as he sets the scene in a familiar American landscape.

“School Day” does something similar. Writing about the slow-burn misery of high school as he himself was in his 30s, Berry uses his experience as an older man to enrich the song’s action: “Back in the classroom, open your books / Gee, but the teacher don’t know how mean she looks.”

What a line! All at once Berry is telling us what it feels like to be in the classroom — what it feels like to be one of his teenage fans, in other words — and what it feels like to be the teacher doing her best to civilize these little twerps.

The pinched, springy sound of his guitar — like someone winding an antique clock — only adds to the sensation, physicalizing the long minutes until the school bell finally rings.

Berry’s catalog is filled with such lyrical and musical complexity, be it the picture of American ambition in “Johnny B. Goode” or the depiction of American oppression in “Brown Eyed Handsome Man,” which opens by putting us in a courtroom with a man “arrested on charges of unemployment.”

And then there’s his vision of America itself in “Promised Land,” Berry’s epic travelogue from Norfolk, Va., to Los Angeles in which he conjures a vast sprawl of highways, train tracks and overnight flights serving T-bone steaks.

Yet it wasn’t just his words that distinguished his music. It was the way he sang them, enunciating as crisply as that mean schoolteacher might have while somehow communicating his essential rebelliousness.

Listen to “Roll Over Beethoven,” to see how sure he is of himself and the wild, bumptious tune he’s written: This isn’t a crass rock ’n’ roller writing off yesterday’s masters; it’s game recognizing game.

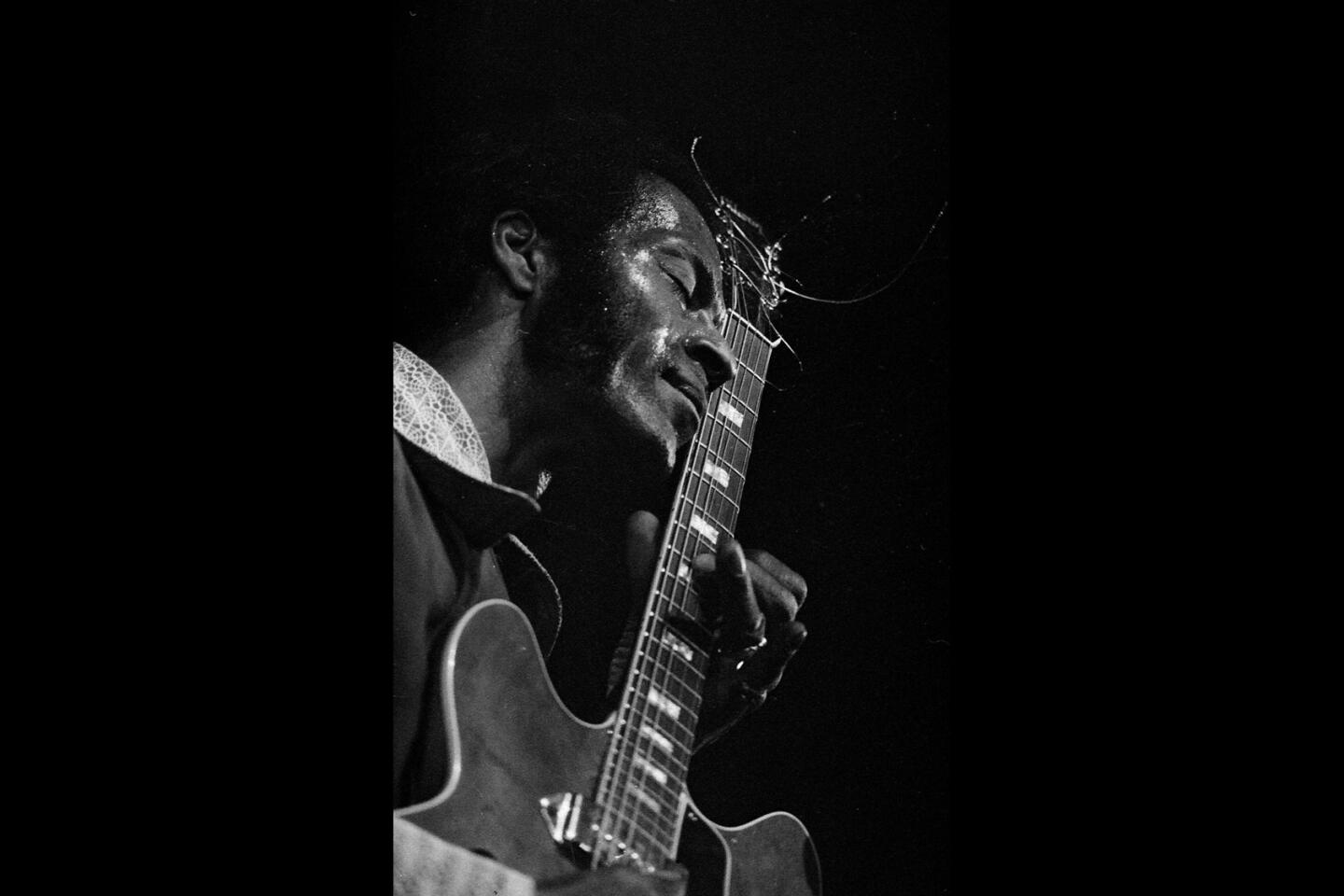

As a guitarist, Berry saw infinite variety in a handful of moves, from the splintery lead lines in “Johnny B. Goode” and “Carol” to the fuzzy jangle of “Sweet Little Sixteen” and “Rock and Roll Music.” And like a jeweler with a loupe, he knew the intricate contours of each of his riffs, as he demonstrated in a much-discussed scene from Taylor Hackford’s 1987 documentary “Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’ Roll.”

Rehearsing “Carol” with a band that includes the Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards, Berry keeps halting the music, pointing out little mistakes Richards is making with the main lick.

“You wanna get it right,” Berry says, “let’s get it right.”

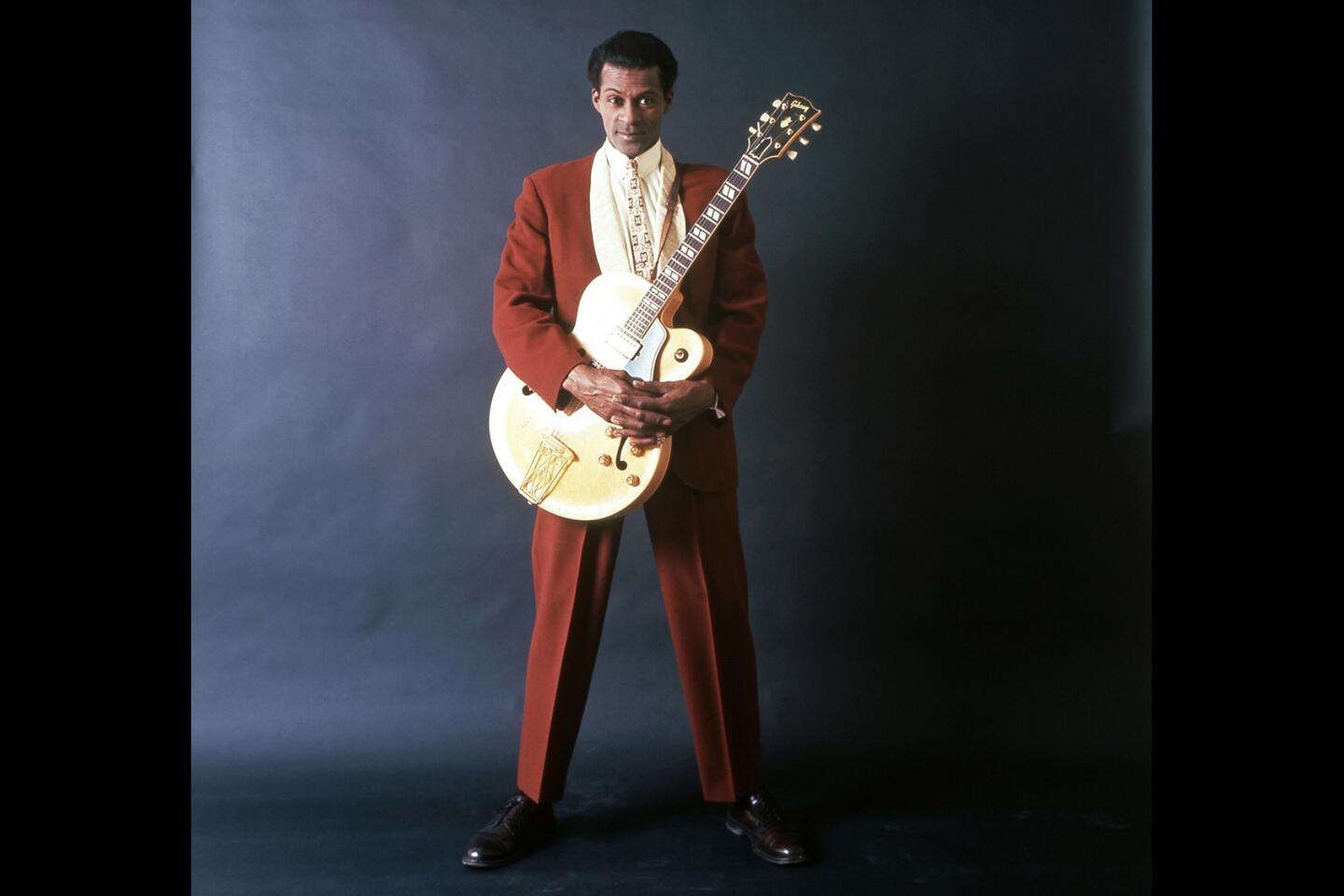

In that sharp edge, those who knew Berry offstage likely recognized another of his contradictions, and that was the prickliness of an artist whose legend was rooted in his ability to make music about having a good time.

Some of his coarseness came in the pursuit of admirable goals — his insistence, for example, that he be paid for his work.

But if Berry’s sticking up for himself inspired future rockers to do the same, so too did his reputation for mistreating women help establish a harmful norm. In 1990, he was sued for allegedly videotaping women in the bathroom of a restaurant on his Missouri estate; he denied the charges but paid a settlement.

Yet Berry never quite went along with the notion that his party songs reflected his (or anyone else’s) mere happiness.

Speaking to The Times in 1987, he said he’d given up chasing joy as a way to avoid encountering its emotional opposite.

“People have killed themselves over the lack of glory,” he said. “They have also killed themselves from the depths of degradation.”

There was nothing ready made about the man who observed that.

Twitter: @mikaelwood

ALSO

10 Chuck Berry songs that inspired the rest of rock ‘n’ roll

Chuck Berry talks music, race and his ‘difficult’ reputation

The time Chuck Berry and Keith Richards clashed onstage: ‘You’re going to have to let me lead’

UPDATES:

12:54 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details about Berry’s music and life.

This article was originally published March 18 at 9:50 p.m.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.