Agnès Varda on making films, admiring Angelina Jolie and winning a ‘side Oscar’

For most artists, winning an honorary Academy Award would mark the culmination of a long and extraordinary career. Few careers in any field are as long or extraordinary as that of Agnès Varda, but as she sits down at Le Parc Suite in West Hollywood, the 89-year-old Brussels-born, Paris-based director greets the prospect of her accolade more or less the same way that she greets everything else — with great equanimity, mild perplexity and a winsome sense of humor.

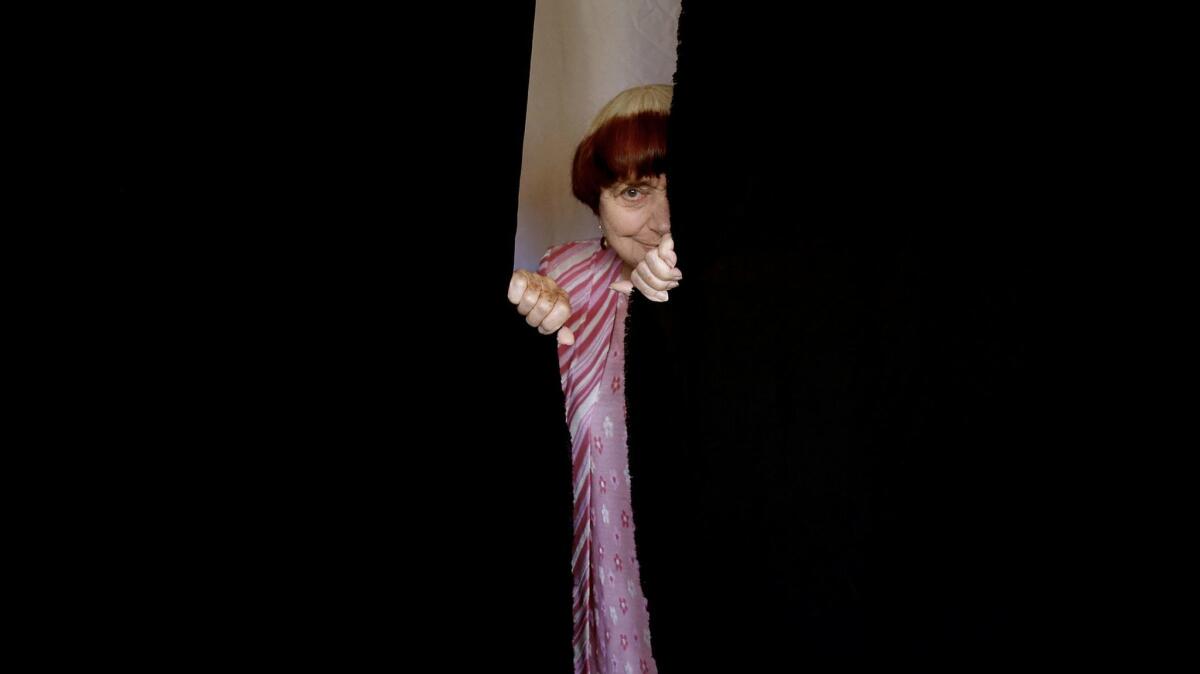

With her duo-tone pageboy haircut, her diminutive stature and her wonderful openness to new experience, Varda would be an enchanting screen presence even if she were not also one of the world’s most innovative filmmakers. Often described as “the godmother of the French New Wave,” though she is more properly thought of as a member of the Left Bank movement, she made her feature directing debut with “La Pointe Courte” (1955), a portrait of a crumbling marriage set in a Mediterranean fishing village, steeped in documentary and neorealist techniques.

She followed that with the real-time landmark “Cléo From 5 to 7” (1962), which, along with later standouts like “Vagabond” (1985), her daringly nonlinear study of a female drifter, confirmed her implicit, forthright feminism as well as her desire to advance the language of the medium. Over the past several decades, she has never lost her flair for mixing things up — color and black-and-white, video and film, documentary and narrative, past and present. While she has said that her latest documentary “Faces Places,” a richly empathetic tour of rural French life co-directed with the 34-year-old visual artist JR and currently playing at Laemmle’s Royal Theatre, will be her last theatrical feature, it’s hard to imagine that adventurous magpie spirit abating anytime soon.

You’ve spent quite a bit of time in Los Angeles before this.

I love the city. I came here for the first time with (my husband) Jacques Demy in ’67, and I made a film in ’68 called “Lions Love ( … and Lies),” with Viva, James Rado and Gerome Ragni, who had written “Hair.” So it’s really the hippie time, and it was an incredible liberation because everything was free, men had beautiful shirts with flowers, everybody loved everybody. Then I came back here 10 years later and I made “Mur Murs,” about the murals. In 1980, nobody spoke about street art. Thirty-five years later, it’s everywhere. The street artists are famous now. I love the people in Los Angeles.

And now you’re back in L.A. to accept an honorary Oscar.

How could somebody think that one day I would be recognized by the Hollywood world? This is strange for me.

— Agnès Varda

A “side Oscar.” Honorary, yes. What is honorary? I have received an honorary César. I have received an honorary Palme d’Or in Cannes. So it’s like the academy is saying, “That old lady has been working so continuously for cinema, at some point we should recognize that she worked.” I feel like it’s recognition of my decent work. I made my first film, “La Pointe Courte,” in 1954, a radical film. How could somebody think that one day I would be recognized by the Hollywood world? This is strange for me. Do they give four little Oscars (to the honorary winners)? Or are they the same size?

I think they’re the same size.

Are they half-finished-size Oscars? Because the ceremony is held in November, and not in February or March? Do we have to give a little speech, even if we’re at tables? I know Angelina Jolie will be the one to present the award to me. She’s an incredible, interesting woman. She has not only the talent of acting, but she has a position in life that I like about her. I’m very feminist, as you know, as everybody knows. So the position she takes regarding women, children and her own stardom — she uses this in a very interesting way.

What does winning an honorary Oscar mean for you and your career at this point?

I don’t think it will help because I no longer find money for films; this is it. Making cinema that goes into theaters has become so difficult, because we are in competition with some incredible films, well made, with a lot of special effects. That’s what young audiences want. Big films make money because they cost money. This is the Hollywood system. I don’t belong to it.

So [getting this award] is a surprise, and I love good surprises. So I take it, I say, “Thank you, I’m delighted.” But I feel it has been a mistake. No, it’s not a mistake, because I know that this honorary Oscar — it goes to decent people. Last year I know there was another documentary filmmaker, Frederick Wiseman, who got it.

Jean-Luc Godard got it too.

Godard is more assertive than I am, even. He’s an adventurer. And he does things I really love and respect. We need people like him. He doesn’t make money, either, but I think he’s necessary. Some people are necessary. What do you think “Metropolis” made at the time, when it came out? Think it was a success? No. But it’s an incredible, beautiful experience.

Is there a difference between how your films are received at home in France, and how they are received abroad?

Some people have recognized my films as being valuable in the search for what cinema can do. The search is not as violent as it is in Godard’s films, but [more in line with the films of] Alain Resnais and Jacques Demy, doing things that have not been done before. But I am in the margins of cinema. In France my films are very well-known, but they don’t make what you’d call big money. They make enough money to survive, but there’s no way that I’m bankable. I cannot say, “I wish to make a film. Give me the money.” It doesn’t work like this. I’ve never had one film made with easy money, never. Even being old, even having a closet full of awards — I got a Golden Lion, I got a Silver Bear, I got a lot of animals. But each time I want to make a film, it’s the same. I’m not bankable.

I really wish to be on the side of a daydream, of utopia. I want to be on the side of the question: Could art help people?

— Agnès Varda

Your last several films have been documentaries, many of them intensely personal.

In a documentary you have to be modest, because the subject is the people you film, and I love that. By making a documentary, I still learn something from real life. And then I try to make a link between the film and the audience. So far it’s worked. In “Faces Places,” JR and I earned the respect of unknown people, we shed light on them, we listened to them. We had a good time, and I felt that it was one more documentary in which I question: How can we approach people who have no power? How could we achieve more empathy, more understanding between people?

You got to know a lot of people during the making of “Faces Places,” and you made a point of never asking them about their politics.

We never spoke about politics with people, and we knew that maybe some of them were going to vote for things we don’t like. We decided it was best to skip the subject. I didn’t want to know. They exist as persons. They deserve that. It’s good to speak to them, to listen to what they want to say, how they feel.

And look, it’s not that I don’t know about the world, the disgusting world — the news on television, the news in the papers, the messages of hate, the separations between religions and between countries, the horrible experiences of migrants all over the world. But I don’t want to add another layer of drama, another layer of terrifying life. I really wish to be on the side of a daydream, of utopia. I want to be on the side of the question: Could art help people? Could cinema help people think about their lives?

Editor’s note: The Times will profile each of this year’s four honorary Oscar winners — Charles Burnett, Owen Roizman, Donald Sutherland and Agnès Varda — leading up to the Governors Awards on the evening of Nov. 11.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.