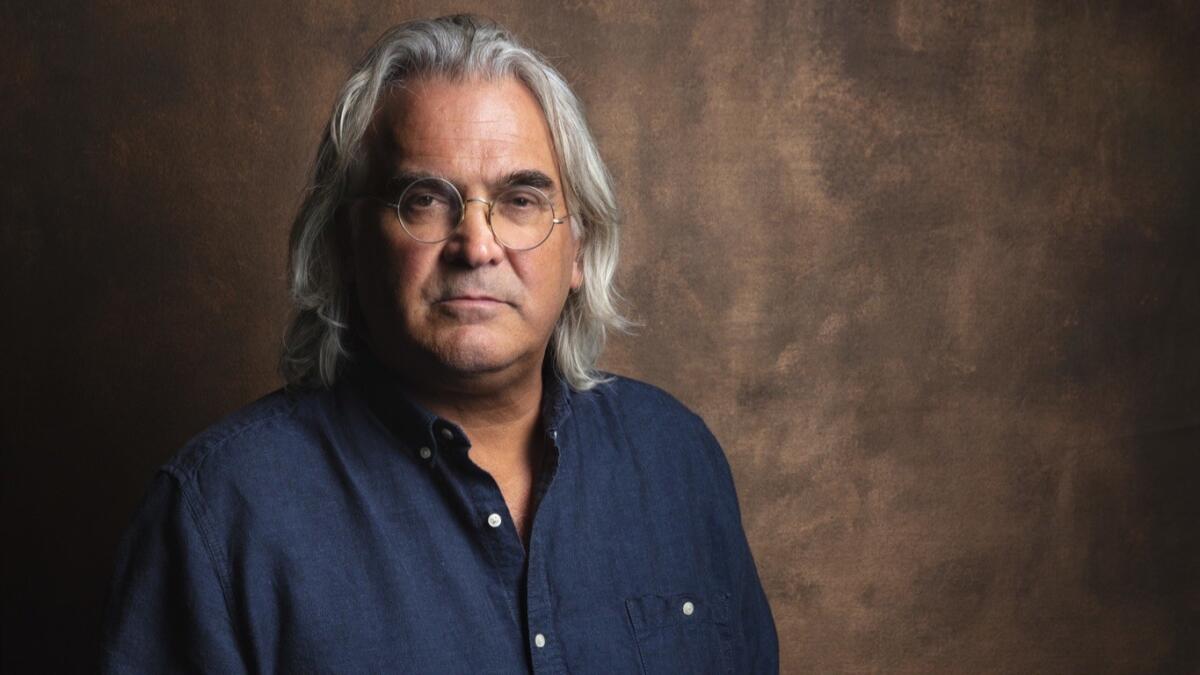

With ’22 July,’ Paul Greengrass tackles Norway’s deadly 2011 terror attack and the perils of far-right extremism

It’s safe to say virtually every Norwegian can remember where they were on July 22, 2011. That was the day a lone-wolf far-right terrorist named Anders Behring Breivik set off a car bomb in the government district of Oslo and then later opened fire on a summer camp on the nearby island of Utøya, killing 77 people in the country’s deadliest attack since World War II.

Actor Anders Danielsen Lie, who plays Breivik in director Paul Greengrass’ new film about the attack and its aftermath, “22 July” — which is now playing in theaters across the U.S. and available on Netflix — was at a wedding that day in northern Norway. “I spent most of the day on the phone trying to make sure that all my friends and family were safe in Oslo,” he says.

Jonas Strand Gravli, who plays Viljar Hanssen, one of the young survivors of the shootings on Utøya, was driving to a cabin outside of Oslo that day with some friends. “I just wanted to get back to Oslo,” he says. “I feel like every Norwegian was affected by it in some way. Everyone knew someone who knew someone.”

Like many outside of Norway, the British Greengrass — who, along with directing three installments in the “Jason Bourne” action franchise, has dramatized real-life attacks in such films as “Bloody Sunday,” “United 93” and “Captain Phillips” — heard the news from afar but didn’t follow it particularly closely at the time. It wasn’t until a few years later, when he was trying to develop a project about the global migration crisis, that he began to research the event in more depth.

“I’d had a lot of fun doing the Bourne movies, but from time to time, I’ve done films that are trying to explore the world around me as I see it,” Greengrass says. “The more I thought about it, the more I thought the migration crisis was only one part of a bigger problem: this political typhoon running through Western democracies, a full-scale revolt against globalization that’s leading to right-wing populism, protectionism, nationalism and the politics of identity. And the more I started to think about that, the more I honed in on Breivik as the moment when that became clear.”

REVIEW: Paul Greengrass’ riveting ’22 July’ explores what it takes to overcome an act of pure evil »

Greengrass read journalist Åsne Seirestad’s book about the attacks, “One of Us,” and pored over Breivik’s courtroom testimony about his motivation, in which he remorselessly railed against multiculturalism and claimed that elitist “cultural Marxists” had used Norway as as “a dumping ground for the surplus births of the third world.”

“It was all that rank bag of prejudices,” Greengrass says. “But as I read it, I thought, ‘This is amazing — in 2011, those opinions would have been considered in the wild margins of political discourse. Today, not Breivik’s methods but his worldview, that intellectual framework, is now in the mainstream.’ I thought, ‘Oh, this is not the story of a right-wing terrorist attack — it’s the story of how Norway responded, and that’s really a story about us today and tomorrow.’ ”

Having directed 2006’s “United 93,” which chronicled the hijacking of that flight during the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Greengrass was intensely aware of the sensitivity required to make a film about a traumatic event still so fresh in people’s minds.

The director set about meeting with Norway’s former prime minister Jens Stoltenberg, who is currently the secretary general of NATO, and with the families of victims and survivors of the attack. His aim, he told them, was to raise awareness of the political dangers that the attacks highlighted, not to exploit the tragedy for mere entertainment. He promised to work with an entirely Norwegian cast and crew and to depict the attacks themselves with a delicate balance of unflinching, documentary-style horror and judicious restraint.

Review: Paul Greengrass’ riveting ’22 July’ explores what it takes to overcome an act of pure evil »

“I remember, in one meeting, a gentleman got up, a father whose daughter had died,” Greengrass says. “He said, ‘I strongly support making this film, but I do not want you to sanitize what happened because you would be disrespecting my daughter, and she would not want it either. On the other hand, I don’t want you to sensationalize it or trivialize it or be gratuitous. If you make this film, you’re going to have to make sense of that— and I’ll judge you.’ I said, ‘You’re exactly right.’ ”

Many who were directly impacted by the attacks supported Greengrass’ film, regarding the prospect of a major filmmaker recounting the story in English as the best opportunity to get it out to a wide international audience. (The film follows on the heels of a Norwegian-made dramatization of the attack, “U – July 22,” which has had a very limited release outside of the country.) Still, not everyone in Norway was comfortable with the idea early on, and a petition to try to stop the production gathered some 20,000 signatures.

“I think, as a Norwegian, it will always feel like this is too soon,” says Gravli. “But I think it’s important to make this now because, even though this is a film about a local attack, it has a global impact. The far-right extremist views are still on the rise in the world, and I think it’s important to keep talking about them and what they cost us in Norway.”

Lie had his own hesitation about playing Breivik, who was sentenced to 21 years in prison with the possibility of one or more extensions for as long as he is deemed a danger to society, the maximum penalty under Norwegian law. But in the end, he decided it was important to try to convey what Hannah Arendt, writing about the trial of Nazi SS officer Adolf Eichmann, called “the banality of evil.” (In one of the film’s more quietly chilling moments, Breivik calmly tells the police who have just captured him that he sustained a small cut on his finger in the attack and needs a Band-Aid.)

“When a person has done something like this, we want him to be a monster, we don’t want him to be human,” says Lie, who tried to set up a meeting with Breivik when he was preparing for the role but was declined. “Watching his testimony, I was seeing a person behaving in a totally normal fashion most of the time, and I felt nausea. I felt like I had a responsibility for the people affected by the tragedy to create a truthful and honest portrait of this person.”

From the project’s earliest stages, Netflix — which is making a concerted push into the awards season conversation this fall with films such as “22 July,” Alfonso Cuarón’s “Roma” and the Coen brothers’ “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs” — threw its full support behind it.

Some directors of Greengrass’ stature may have shied away from the company’s distribution model, in which films are offered on its streaming service at the same time as they are released theatrically, if they are released theatrically at all. But Greengrass saw it as the best way to get a film that, given its harrowing subject matter and foreign setting, might otherwise struggle to find an audience in front of as many people as possible – and particularly young people.

“I’ve got young adult kids, 15 up to 30s, and they all were like, ‘Dad, Netflix is the future,’ ” Greengrass says. “I remember my son, who’s a student, saying, ‘None of my friends will go see this movie in an arthouse cinema. But if it’s on Netflix, they’ll all watch it.’ ”

In his career, Greengrass has made a handful of movies, including the “Bourne” films, that are engineered to deliver a fun time at the multiplex. “22 July,” with its depiction of the cold-blooded murder of nearly 70 innocent young people at a summer camp, is decidedly not one of them. Though he’s not sure what project he’ll tackle next, Greengrass says with a grim smile, “Not something that involves death and destruction, that’s for sure. A bit more like a round on the dance floor, I think.”

Nevertheless, while “22 July” may the furthest thing from a mindless Hollywood confection to distract from these politically turbulent times, Greengrass hopes its story of perseverance and commitment to higher ideals in the face of hatred and terror will ultimately leave audiences inspired.

“I didn’t want to make a bleak, nihilistic film,” he says. “These events happen and they’re terrible, but they’re part of our world and they have to be confronted and overcome. And they will be.”

Twitter: @joshrottenberg

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.