Christian Petzold’s ‘Phoenix’ haunted by ghosts of WWII

The nightclub singer returns from a concentration camp, battered and disfigured, roaming like an apparition through a ruined city toward her husband’s betrayal. The war has not yet settled into history, and the chanteuse is desperate to resurrect a charmed life forever lost.

Christian Petzold’s new film “Phoenix” is a stirring exploration of staggering from the ashes into the guilt and denial of personal and national deceptions. With noir shadows and haunting music from Kurt Weill, the movie, which opens in Los Angeles on Friday, visits Germany at a moment when the beautiful memories that steeled victims against the Holocaust are spoiled as the sins of complicity are exposed.

“Phoenix” is Petzold’s second film in recent years to rummage — in understated and forceful ways — through his country’s closet. While “Phoenix” deals with the demons of World War II, his earlier work, “Barbara,” was a love affair set in the stifling grip of communist East Germany. His examination of moral duplicities is reminiscent in spirit of Italian neorealist cinema of the 1940s and ‘50s and, more recently, Romanian films delving into the corruption echoing from the Cold War and through a troubled rebirth to democracy.

Indie Focus: Sign up for your field guide to only good movies

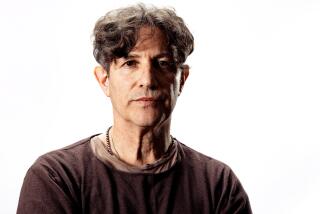

“Who are we? Where do we come from?” said Petzold, 54, a member of the Berlin school of filmmakers whose intimate portraits of relationships are set against social upheavals. “We in Germany don’t have those kinds of movies and I’m a bit astonished and a little bit afraid of that. We are afraid to go back to all those emotions” that came from the war.

Petzold is gifted at shaping suspense, layering the psychological and emotional with evocative cinematography. His films explore how the unreconciled leads to transgression or transformation: “Ghosts” is the tale of an orphan looking for a mother; “Yella” is an allegorical thriller about a wife escaping an abusive husband amid the temptations of capitalism; and “Jerichow” is a parable of immigration and adultery reminiscent of “The Postman Always Rings Twice.”

His turn toward World War II in “Phoenix” examines sensitive terrain. Germans learn about Nazi atrocities in school and live amid Holocaust memorials, but many prefer not to have such ghosts conjured in their movie houses. Over the last decade, notable German films such as “Downfall,” a ticktock reconstruction of Adolf Hitler’s final days in a bunker before his suicide, and “Generation War,” which follows a group of young Germans across killing fields and bombed cities, have brought World War II into sharper, if uncomfortable, focus.

Remnants of past ideology persist at the fringes even today in a country that has become one of Europe’s most tolerant societies. Most Germans were quick to condemn anti-immigration rallies last year staged by neo-Nazis in Dresden and other cities. Yet Germany’s economic and political power, recently on display over the Greek financial crisis, is unsettling to some on a continent at a time when nationalist voices are reverberating and the European Union is under increasing strain.

“Phoenix” is a reminder of the dark side of German ambition. Jewish nightclub singer Nelly (Nina Hoss) arrives home from a concentration camp. Injuries forced her to undergo reconstructive surgery, but she’s convinced that she and her husband, Johnny (Ronald Zehrfeld), can slip back into old lives. Johnny doesn’t recognize her or pretends not to; Nelly plays along, gradually emerging into her former likeness.

But Johnny resists admitting that his wife has returned. “It is like he has an infection inside him,” said Petzold. “He cannot recognize her. His body recognizes her but his brain and soul cannot.” Johnny grows tormented and his secret unravels, a deception that blooms into a shattering realization that lays bare the crimes of both husband and country.

“The threads of a concentration camp survivor’s return to postwar Germany are woven into a masterful web,” said the Guardian in a review of “Phoenix.” “The warped narrative functions as an allegory for the stories that people and nations recount to themselves in order to go on surviving.”

CLASSIC HOLLYWOOD: Sign up for Susan King’s weekly newsletter

The premise of the film “would make Alfred Hitchcock bounce in his seat,” wrote Joe McGovern in Entertainment Weekly. “The plot is just implausible enough to keep the film from greatness, but [Petzold] stirs up a powder-keg metaphor about rebuilding after war. For its quiet sense of mystery and art-house appeal, ‘Phoenix’ might be this year’s ‘Ida,’” which won the 2015 Academy Award for foreign-language film.

Petzold, who wrote the “Phoenix” screenplay, was partly inspired by “An Experiment in Love,” a story by Alexander Kluge set in Auschwitz. For a time, though, the director had resisted straying too far into history. “Ten years ago, I said I hate period pieces. I live in the contemporary world,” said Petzold, who won international acclaim and the director prize for “Barbara” at the 2012 Berlin Film Festival. “But after ‘Barbara’ I see that period pictures are contemporary.”

That is the story of postwar Germany — the specter of the past seeping into and, at times, shaping the present even as younger generations move restlessly ahead with new visions. For Hoss, who has starred in six of the director’s films, “Phoenix” was a “very new way of looking at that period and showing what was in the air, what happened after the Holocaust.... The 1950s of Germany are staring right at you. What do I do with this knowledge?”

“Germany really looked at its history, and still is,” added Hoss, one of Europe’s finest actresses, who last year starred alongside the late Philip Seymour Hoffman in “A Most Wanted Man” and has appeared in Showtime’s “Homeland.” “That is something I really appreciate about this country. It doesn’t deny its history. It doesn’t want this to ever happen again.”

The collaboration between Petzold and Hoss — not a lot of German films make it to the U.S., but theirs have — works largely because of the director’s skill at writing characters that allows Hoss nuance. “Something clicks with us,” Hoss said of the director. “He writes incredible female characters. They’re precise, supple, fine. They leave so much for me to interpret.”

Petzold said Hoss is a prodigious researcher who wrote down everything during rehearsals in their early years of working together. “She’s a beautiful actress. She walks like a monologue,” said Petzold, laughing and adding, “I’ve seen her more than my wife.”

The eerie mood and questions raised by “Phoenix” have intrigued Petzold. He said his next film will be set in the 1940s in the French town of Marseille as refugees hide and hurry to catch boats to Mexico as the German army closes in. Part of him, he said, wants to capture the aura and verve of German filmmakers, such as Fritz Lang and Max Ophüls, who fled to America to escape Hitler.

“The light from Germany went to the U.S.A. in the 1930s,” he said. “We have to bring the light and style back to Germany, especially the noir which was created by Austrian and German refugees.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.