Is it curtains for Hollywood’s bail bondsmen and bounty hunters?

On the gritty side of town, where charlatans, grifters and the unfortunate gather, there is a cranky guy in a suit with a wad of cash who knows, more intimately than your wife, the sins and excuses that put you in cuffs and made you utter those three despairing words: “I need bail.”

The bail bondsman and the bounty hunter have been mythologized in film and television for years. They are confessors and opportunists, the mirrors that reveal how far from virtue we have slipped. Offering cash or chasing rewards, they play between absolution and penance, tracking fugitives and philosophizing — in taverns and around campfires — on the dark heart of human nature.

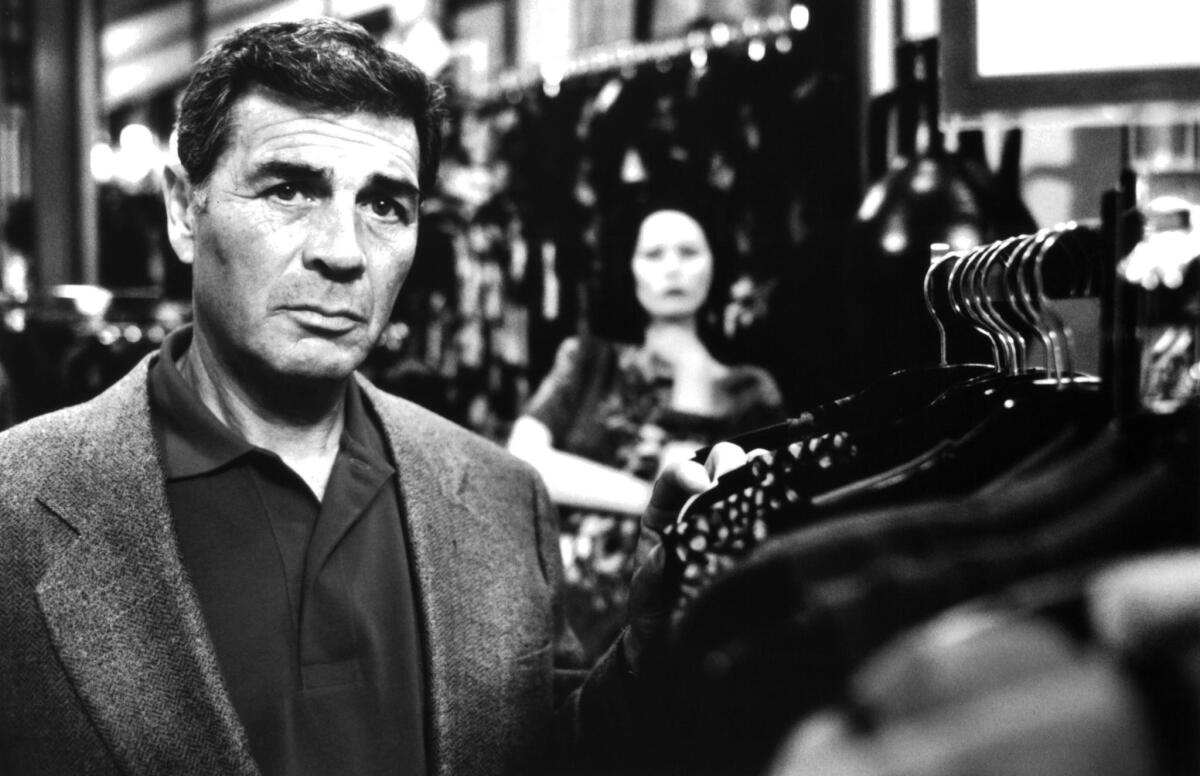

Some, like Max Cherry (Robert Forster) in “Jackie Brown” have a tenderness that makes them susceptible to women at the center of trouble. Max may have a soft spot for a coy smile, but he is no fool. He’s written 15,000 bonds, wears a smart hairpiece, drinks his coffee black when the milk goes sour and knows as soon as Ordell Robbie (Samuel L. Jackson) strolls into his office that things are going to veer violent and complicated.

“You want me to know what a slick guy you are,” he tells Ordell. “You got stewardesses bringing you 50 grand. … Now, you want me to speculate on what you do. I’d say you’re in the drug business, except the money is moving in the wrong direction.” Ordell is an exasperating sort, menace draped in a chair. “This isn’t a bar,” Cherry snaps. “You don’t have a tab.”

Ordell has his own take on Cherry and his ilk: “You know your bail bondsman don’tcha?” he asks accomplice Louis Gara (Robert De Niro) while the two are sitting in a van on a ragged Los Angeles street. “You know all them … is as crooked as a barrel of snakes, don’tcha?”

That brand of underworld charm may be endangered on the big screen. A new law signed by Gov. Jerry Brown will eliminate the practice of a defendant posting cash as a condition for release from prison ahead of trial. It will shut down bail bond offices across California, which accounts for roughly a quarter of the nation’s $2-billion bail industry. The law takes effect next year and bail companies have been collecting signatures in an effort to block the law and bring it to a referendum on the November 2020 ballot.

The posting of bail began centuries ago in Anglo-Saxon England. The Heritage Foundation notes that the origin of the American bail bondsman “is difficult to pin down, but most trace its lineage to late-19th-century San Francisco” when brothers Peter and Thomas McDonough — investigated by a grand jury for running a crime syndicate that included bribery and prostitution — opened a bail bond firm out of their father’s saloon. Many countries have outlawed the practice of private bail, and states such as New Jersey, Kentucky and Illinois are either reforming or phasing out a system many view as unfair to minority and poor communities.

“I always tell people the bail business is disgusting and wonderful,” Miles Soto, a former bail consultant and private investigator in Southern California, recently told The Times. “Some bail agents are of the worst caliber. But when used correctly, bail can be used to help people in a wonderful way.”

The bail bondsman has been a fixture on Hollywood screens since at least 1933, when George Bancroft played corrupt Bill Bailey, a cigar-smoking raconteur and pool shark with a taste for socialites in “Blood Money.” Bailey has a matter-of-fact take on how the world works: “The only difference between a liberal and a conservative man is that a liberal recognizes the existence of vice and controls it, while a conservative just turns his back and pretends it doesn’t exist.”

Cinematic bondsmen and bounty hunters have since galloped across the Old West (Henry Fonda in “The Tin Star”), wrestled with L.A. gangsters (George Raft in “A Dangerous Profession”), careened through space (father-son clones Jango and Boba Fett in “Star Wars”) or blasted their way, bound in black leather and drenched in makeup, through America’s Second Civil War (Pamela Anderson in “Barb Wire”). Bounty hunters and bondsmen tend to be more figures of action than verbosity.

“Help me,” says a shot man to Jeff Bridges’ fugitive-searching marshal Rooster Cogburn in Joel and Ethan Coen’s “True Grit” remake from 2010.

“I can do nothing for you, son,” says Cogburn, who raises his six-shooter and finishes him off.

John Wayne’s Cogburn was no more sentimental in the 1969 original: “You can’t serve papers on a rat, baby sister,” he said after shooting a cornmeal-stealing saloon crook he’d verbally served with “a rat writ, writ for a rat.” “You gotta kill him or let him be.”

Steve McQueen spent his early career playing an Old West bounty hunter on the TV series “Wanted: Dead or Alive” and in his final film, “The Hunter,” he played the real-life, modern-day bounty hunter Ralph “Papa” Thorson (1980).

Crime’s account keepers

Etched into our history and folklore, bounty hunters and bondsmen are most often crime’s supporting players, much like the pawn shop owner who often shares the same street of whispers and broken neon. They live between bad and good, crisscrossing through morality, vengeance and justice. They navigate the gray area where so much life unfolds, the place where men and women make accounts and factor in whether redemption is necessary if a soul can make one last score and slip away like a ghost through a keyhole.

Giovanni Ribisi’s Marius, just out of prison in the Amazon series “Sneaky Pete,” was hoping to skate away from his troubles when he assumed the identity of his former cellmate Pete and joined his new family’s bail bond business as a skip tracer — a criminal trying to outsmart other criminals.

One of the most memorable bondsman was Eddie Moscone (Joe Pantoliano) in “Midnight Run.” A screamer in cheap shirts, he worries he’ll lose the bail he’s posted if bounty hunter Jack Walsh (Robert De Niro) doesn’t get Jonathan “The Duke” Mardukas (Charles Grodin), an accountant who embezzled from the mob, out of New York and back to authorities in Los Angeles. In one scene, you can feel Moscone’s pain when Walsh calls him for more travel money.

“What do you need with $500 on a bus?” asks Moscone. “Why the ... aren’t you on a plane?”

Clint Eastwood’s poncho-draped gunslinger and bounty hunter in Sergio Leone’s films — “For a Few Dollars More” and “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” — W rides a dusty, scoured land of beady-eyed smoking men, outlaws, rewards, whiskey and corpses. The 1960s spaghetti westerns, part of Leone’s “Dollars” trilogy, set the template for the restless, solitary and violent men that would shape Eastwood’s career. He twirls six-shooters, fronts a perpetual cigar and has the squinted gaze of someone sizing you up for a coffin.

Like the best bounty hunters, he’s plainspoken about his intentions.

“Well [there’s] such a big reward offered on you gentlemen that I thought I just might tag along on your next robbery,” he says in “For a Few Dollars More.” “Might just turn you in to the law.”

ALSO

An Appreciation: Burt Reynolds ran through my youth as a charmer and a spinner of wiles

Paul Schrader wrestles with the sacred and profane in his new ‘First Reformed’

From ‘Sling Blade’ to ‘Goliath’: Billy Bob Thornton finds his peace

See the most-read stories this hour »

Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.