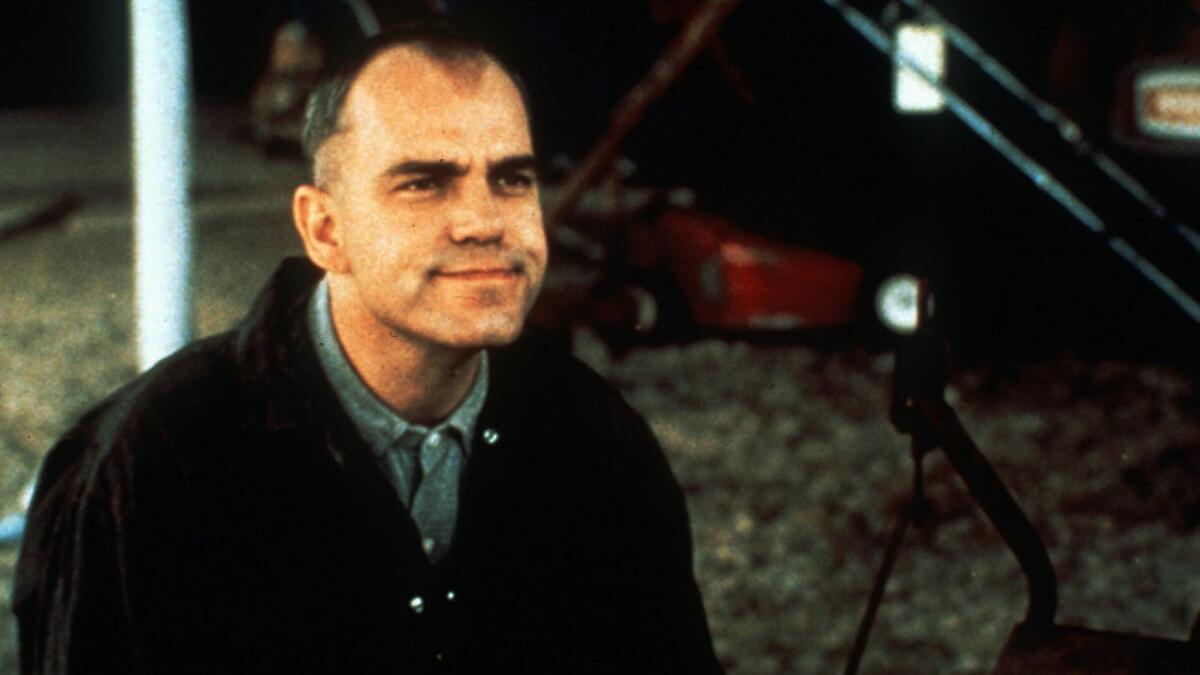

From ‘Sling Blade’ to ‘Goliath’: Billy Bob Thornton finds his peace

The bar half-lit, his beer quarter-full, Billy Bob Thornton smiled like a guy fencing stolen watches. He wore a long, dark coat, hat pulled low, and one sensed he could slip away with no one, not even the two ladies tucked in the corner, being the wiser. He sipped and narrowed his eyes at a passing face.

Thornton can come across as a menacing whisper, a man who would guard your lunch money but steal your wife. You have to watch him, like you have for many years, to see what he might do next, this onetime boy from a shack in the woods who loves Faulkner, wears rings on his thumbs, frets about the world and has figured out that television, with its intricate characters an deep story lines, suits him.

His series “Goliath,” for which he won a Golden Globe, starts its second season on Amazon on June 15. The existential tale, created by David E. Kelley and Jonathan Shapiro, dives into the righteous, flawed, intense, if reticent, soul of Billy McBride, a boozed-up, motel-living lawyer whose integrity is commensurate with his understanding of evil. Rumpled and undeterred, he believes in justice but is not sure about the law. McBride gets mixed up with a dirty cop, a woman who might be conning him, a psychopathic developer and a drug lord with an amputation fetish.

“I don’t play the part any different from what I am. I’m a guy who doesn’t think life is fair,” said Thornton, gazing from the back booth at Chez Jay, a Santa Monica bar that over the decades has seen its share of transgressions. “The story goes to a place that’s really crazy. The whole thing started out as a version of Paul Newman in ‘The Verdict’, but I see it as that combined with Jimmy Stewart in ‘Vertigo’ or ‘Rear Window.’ This season is a little more Hitchcockian.”

Thornton is like a skip in a record, a crack between a lyric. His characters, including the mentally slow handyman in “Sling Blade,” the tormented prison guard in “Monster’s Ball,” the self-loathing thief in “Bad Santa,” are men askew, off-key notes in need of soothing. Some, such as Billy McBride and Coach Gary Gaines in “Friday Night Lights,” are wells of decency and resolve. They know the line between honor and shame. But Thornton, as he did with sedate hit man Lorne Malvo in the FX series “Fargo,” does sinister like he was born to it.

“They always want you to scream. Casting directors, producers, directors, audiences, all want you to scream, especially when you’re playing a bad guy” he said. “But the fact of the matter is they must not have known that many bad guys, because real bad guys don’t scream. You never hear them coming.”

Thornton is the “most subtle actor I’ve ever worked with,” said “Goliath” showrunner Lawrence Trilling. “He seems to be doing nothing while at the same time giving you everything emotionally. The joke that Billy always says when directors come in try and tell him to be more emotional, he says, ‘Hey, I have the same look in my face whether I’m eating a ham sandwich or killing my mother.’ He understands it’s all about context.”

Thornton sat with his back to a mirror in Chez Jay. Twinkly lights surrounded him, along with models of tall ships and pictures of Sinatra and Monroe; a mounted yellow tuna caught by Gen. George S. Patton hung above the cash register. The bar, replicated as a set for “Goliath,” is dense with folklore and mischief, a place where movie stars, script writers and politicians have whiled away dark hours. Owner Michael Anderson, who looked like he just docked a boat, roamed past a table of men who were drinking wine and squinting toward a square of light at the door.

The actor let it unfold, as if in a scene that need not be hurried. Nina Arianda, who plays McBride’s whirlwind sidekick, Patty Solis-Papagian, said Thornton has an innate ability to stay in the moment: “You melt into the situation. You get over yourself and you focus on the scene and the part. That can only come from somebody being that present and that full. It’s second nature with Billy. It’s almost involuntary. It’s a God given gift. It makes you in it with him right away.”

Thornton was raised “in the middle of the woods” in Arkansas, in a house that had no electricity or plumbing: “The kind of place where people who don’t have money live.” The son of a psychic and Korean War vet who became a teacher, Thornton, whose younger brother died in 1988, said, “I’m severely dyslexic and have obsessive-compulsive disorders and a lot of other things. Real bad anxiety and I have a paranoia, a fear of death, a fear of sickness, the same things for all the people I love. I’ve had it since I was 11 or 12. I always had intensity. It just lived in there.”

He gravitated toward movies and books. “My wonder about the rest of the world drove me,” he said. “All we had was imagination.”

He was a stand-out baseball player and later became a singer-songwriter. His country-rock/rockabilly band, The Boxmasters, will play in July at The Mint in Los Angeles. He’s been married six times, including to Angelina Jolie, whose blood he wore in a locket around his neck in a relationship that now seems a curious artifact from a twilight zone, and his current wife, Connie Angland, a puppeteer and special effects technician. At 62, he carries a sharp notion of what was and what’s been lost.

“When I was a kid, the whole idea behind going to see a movie or a band or reading a book was that you went into it wide-eyed and innocent, wanting to like it,” he said. “But somehow a screw got turned over the years and it tightened everything up to the point where it’s exactly the opposite. People go to these things now wanting to hate it. That’s the sad part of it. People now go to a concert with their arms folded, going, ‘OK, let’s see if Bob Dylan was as good as he was when I saw him in ‘89.’ ”

The venom and meanness on social media bother him. It’s become a world, he said, where “people want to take someone down” and the audience, plugged-in and insatiable on Instagram and Twitter, demands to be the star. “It happened when the business people started relying on the audience to make the right formula for toothpaste and cheese puffs,” he said. “But art is creation, someone’s vision.” If the audience is allowed to dictate art, he added, “then you’re just carpenter building a house to someone’s specs.”

The art of subtraction is essential to his skill as a writer and actor. In the first season of “Goliath,” Trilling asked Thornton to show a more battered look while McBride winced into the sun with a hangover. “I said, ‘I’d love to see that you’re a little more hungover,’ ” said Trilling. “And Billy’s like, ‘I am hungover. This is what it looks like.’ He looks at scripts and rather than want to add lines for himself, he’ll want to cut lines. He’ll say, ‘I don’t need to say this. Let me just show it.’ ”

After moving to Los Angeles to act, write and join a band, Thornton took a job as a waiter at a Christmas party, where he met director Billy Wilder. They talked and Wilder urged him to get into screenwriting. He took the advice and won an Academy Award for adapted screenplay for “Sling Blade” in 1997. He has a novelist’s eye, saying of Tom Waits, whose songs are littered with Thornton-like characters: “If Oliver Twist was a real story and Tom Waits was Fagan, I would have been swiping people’s wallets for him.”

He can be just as perceptive when deciphering himself. He hasn’t had a screenplay turned into a movie for years, and his forays into directing, including “All the Pretty Horses” (2000), adapted from the Cormac McCarthy novel and subject to drastic cutting by Sony and Harvey Weinstein (he did not want to talk about the disgraced producer), have been uneven. His “Jayne Mansfield’s Car” (2012) dropped quickly out of sight. Perhaps it’s earned wisdom or a shade of bitterness but Thornton, who has twice read the Bible from cover to cover, has figured out his place — at least for now — in the constellation.

“I don’t think the audience cares about what I have to say anymore. I think they still care [about me] as [an] actor,” said Thornton, mentioning his early influences of Erskine Caldwell and Tennessee Williams. “I think I’m obsolete as a writer and director. I think I would probably come across as the old guy saying The Beatles are better than the music now. Personal stories seem to be less important right now. Issue stories are important. My issues are things you can’t write about anyway. A) it gets you in trouble, and B) nobody’s going to listen.”

He misses the independent film renaissance that two decades ago produced “Sling Blade.” He doubted such a movie would get made today, “or if it did, it’d get some crummy little distributor and no one would ever see it.” But “Fargo” and now “Goliath” have given him layered stories and idiosyncratic characters, the kind he found years ago in gothic Southern novels in a time before Hollywood wanted to make $1 billion on a movie.

“I think right now, Amazon and these places have taken the place of those movies that are dead. When the independent film boom happened, people wanted that. And I think now, people are turning to shows like ‘Goliath’ and all these others. TV is bringing back the no-holds-barred stories. That’s where that [creativity] lives. If I did go back to writing and directing it would be in that area.”

He’s reminiscent of a soul out of Faulkner or Flannery O’Connor, tormented, wise, funny, a slanted way of seeing things. It was pushing 4 p.m. The bar was almost empty. He stayed a little longer, pondering the Kennedy assassination and how an actor must make language fit him. The sky over the ocean was gray; it felt like rain, but he only lived up the road a bit. He stood, a wisp of a man in a big coat, and left his beer on the table.

ALSO

Paul Schrader wrestles with the sacred and profane in 'First Reformed'

Ethan Hawke lets us in his editing room and reveals what Philip Seymour Hoffman taught him

Mary Steenburgen knows how to coax a laugh but is equally at home with the dark side

Rage and wonder in 1968: The year war came through the TV and I felt pieces of childhood ending

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.