The real Frida Kahlo comes alive in a London exhibit

LONDON — Frida Kahlo’s art is celebrated worldwide, but it’s her personal identity that’s at the heart of a new exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

The recently opened exhibit, “Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up,” traces Kahlo’s persona through objects, photographs and clothing, as well as notable works and painting by the Mexican artist herself. The majority of the pieces and artifacts have arrived in London from the Blue House, the home in Coyoacán, Mexico, where Kahlo was born, lived and died that now acts as a museum. Most of the material has never been displayed outside Mexico before.

“I felt like I met Frida for the first time through her archive,” said Circe Henestrosa, the co-curator of “Making Her Self Up.” “Someone who loved perfume, who was very feminine, who enjoyed dressing up, who didn’t let her disabilities define her. She defined herself on her own terms.”

One of the most striking inclusions is the artist’s prosthetic leg, which she fashioned with a red leather lace-up boot and Chinese embroidery following an amputation in 1953.

“Her prosthetic leg is very interesting for us to see how contemporary she was,” Henestrosa said. “She was ahead of her time — that’s why she’s so relevant today. She decorated her leg the way she did her art. Why would a prosthetic leg be ugly? Can’t it be beautiful?”

Henestrosa initially included many of the pieces in a 2012 exhibit in Mexico City entitled “Appearances Can Be Deceiving: The Dresses of Frida Kahlo” and has since worked to bring Kahlo’s well-preserved clothes to a broader audience. Her collaboration with the Victoria & Albert Museum offers an opportunity to explore Kahlo’s aesthetic and identity in a deeper way, particularly with the help of researchers who have been about to shed new light on many of the objects.

“It’s been four years in the works,” Henestrosa noted. “Anything you want to do with Frida Kahlo you have to plan well in advance, especially when you want to have paintings. For this specific show we wanted to have a very clear dialogue between the paintings and the outfits.

“One thing we wanted to do with this collaboration was to involve a lot of experts. When curating an exhibition it’s very important to have a 360 lens where you involve art historians, jewelry historians, fashion curators. And we’ve discovered new things, like her Chinese skirt — she used to get these pieces from Chinatown in San Francisco — and one is from the Chin dynasty.”

More than 200 pieces are on display in the exhibition, including personal items like medication and jewelry, as well as 22 vibrantly colored and multi-textured dresses worn by Kahlo and seen in her paintings. The majority of the objects were discovered in 2004 when Kahlo’s bathroom in the Blue House was unsealed 50 years after her death in 1954.

Makeup, such as Kahlo’s eyebrow pencil and preferred Revlon “Everything’s Rosy” lipstick shade are displayed alongside iconic portraits by photographer Nickolas Muray, which showcase her brilliant red lips, as well as many of the dresses in the exhibition. Plaster and leather orthopedic corsets, painted and worn by Kahlo, reveal the artist’s refusal to succumb to her medical issues, which began during a childhood bout of polio and continued after a near-fatal accident at 18, and her ongoing interest in aesthetic beauty. These details offer a new perspective on Kahlo and give the viewer a greater sense of her as a person rather than an image.

“It’s an approach that has allowed a more in-depth appraisal of Kahlo’s genius as an artist,” said Claire Wilcox, co-curator of “Making Her Self Up” and senior curator of fashion for the V&A. “It also helps us to understand her in a more three-dimensional way than has previously been possible.

“A lot of these costumes we can recognize from self-portraits and photographs, but to actually see them and the material properties of them and see the little bits of paint on the clothing — because she did paint in these garments — help us to piece together the significance of her. She was an artist, but she was also somebody who defied their disabilities. She didn’t allow herself to be defined by what had happened to her, and on many levels we see the very human side of her here.”

The curators at the Blue House have worked to catalog 6,000 photographs, 22,000 documents and 300 personal items, all of which were enclosed in the room at the behest of Diego Rivera, Kahlo’s husband. “Making Her Self Up” unveils these pieces in chronological and thematic order, as well as investigating the relationships between Kahlo and her family, her illness and her style.

One of Wilcox’s favorites is a necklace that Kahlo made of metal milagros, small tokens left in a church or shrine as thanks for an answered prayer. These particular milagros are shaped like arms and legs, presumably made in response to Kahlo’s problematic right leg that was later amputated, and threaded together in a large necklace over the course of 15 years.

“She had, of course, rejected Catholicism,” Wilcox explains. “What you get is her adopting the drama of the church, but not subscribing to the beliefs. I do find this very touching and it’s beautifully crafted. That’s the other thing — nothing of her was accidental or careless. It was all intentional.”

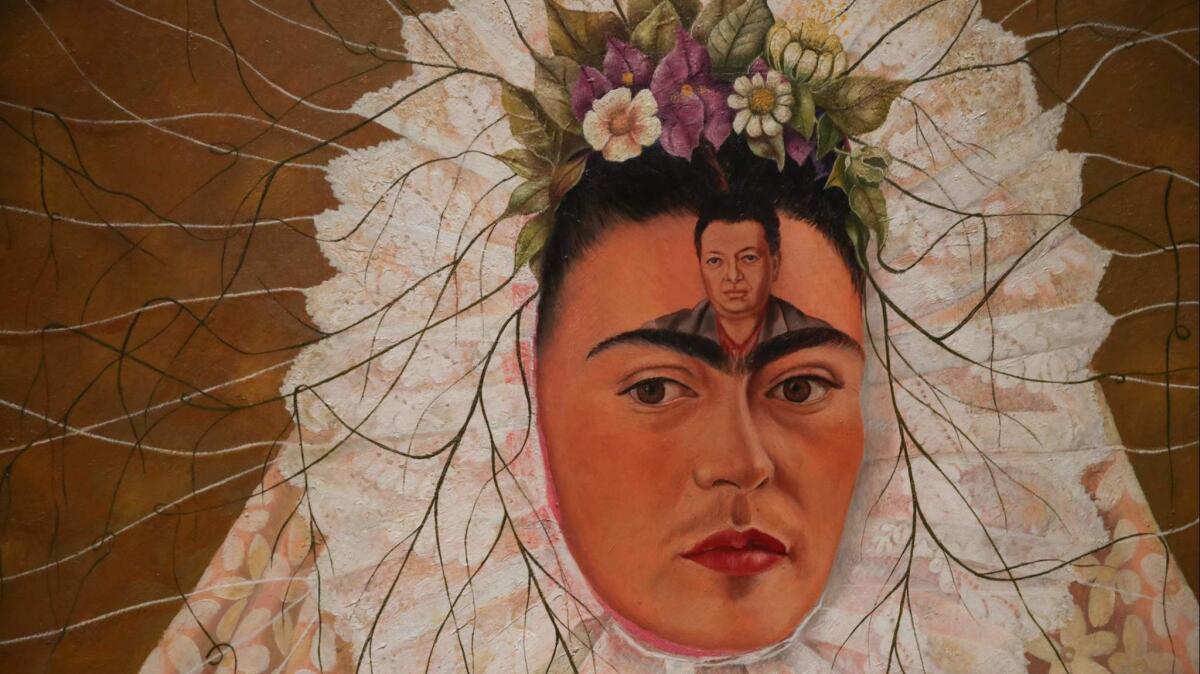

Several of Kahlo’s self-portraits are included within the exhibition rooms, but they are not the focal point. Her 1933 work “Self-Portrait With Necklace” is aptly juxtaposed near a pre-Columbian strand of jade beads, the same ones worn in the painting with the central stone erased. Kahlo’s interest in painting herself began when she spent a year recovering from her accident and her parents placed a mirror in the canopy of her bed.

“She faced up to herself through her self-portraiture,” Wilcox said. “It was her managing the situation she found herself in. In looking at this exhibit, I hope [visitors] understand more about why she painted herself. I hope they realize that she was a real pioneer, both in terms of her art and the way she lived her life, the way she dressed, the way she existed as a dominant personality in a man’s world. She’s curiously timeless.”

For Henestrosa, “Making Her Self Up” is also an opportunity to showcase the dynamic cultural heritage of Mexico. The curator hopes that the exhibit, which continues at the V&A through Nov. 4, will move to the United States, where it may have even stronger relevance.

“With so much political turmoil it’s salutary to have this exhibition of a Mexican artist who is so talented and who has been appropriated by so many people,” Henestrosa believes. “To voice our views is important, and I think that’s what she did. She’s a reminder of who we are. The way she portrayed her Mexican identity is something I feel very proud of. As Mexican people we should feel very proud of our culture and who we are.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.