Why we talk about Zaha Hadid’s gender and ethnicity even though her architecture transcended both

Zaha Hadid, shown in West Hollywood in 2004, pushed the field of architecture forward, toward ever more complex, organic shapes.

To say that the sudden death of Zaha Hadid last week has left a gap in architecture is an understatement.

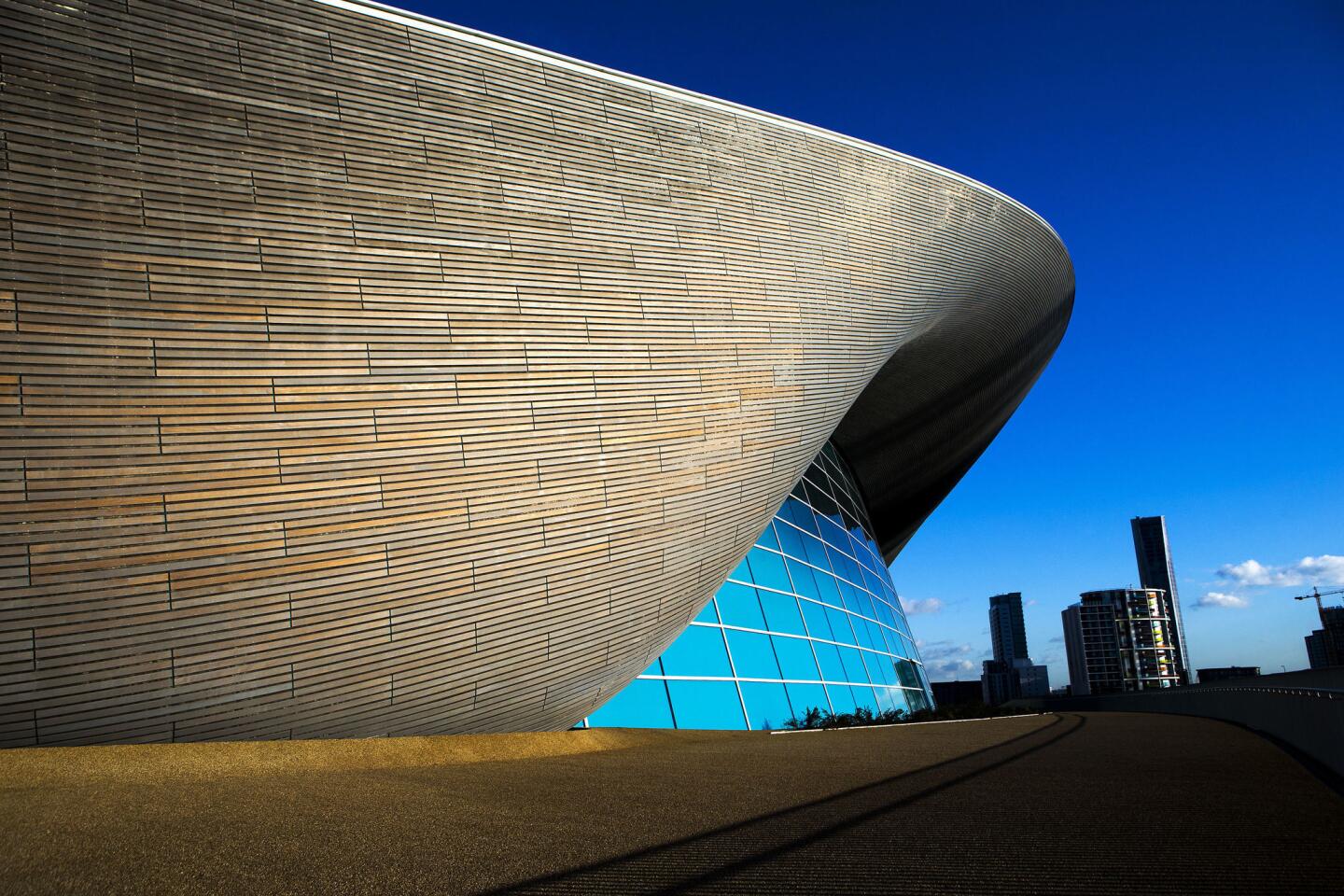

She was a woman in a field dominated by men. An Iraqi-born, secular Muslim who made her home in clubby Protestant England. A flamboyant, cape-wearing figure who was recognizable, Madonna-like, by simply her first name. Most important, she was an architect who pushed the field forward, toward ever more complex, organic shapes that seemed to take their inspiration from the webbed patterns of biological tissue and the globular shapes of cells.

“She charted new territory for all architects with her vision,” architect Sharon Johnston, founding principal at Johnston Marklee, an L.A.-based firm, stated via email. “Zaha’s passion, personality and sheer talent were all essential to her success and her undeniable importance in the history of contemporary architecture.”

She was far more interested in pushing the boundaries of design than of society. And yet, there’s no denying that Hadid’s gender and ethnicity were part of what made her an outsized role model for so many. Hadid, after all, was the first woman to win the Pritzker, architecture’s most prestigious prize, as well as the first female to be awarded the Royal Gold Medal by the Royal Institute of British Architects. She was, as Kriston Capps notes over at Citylab, the first real-deal female starchitect — a figure whose name and designs resonated way beyond the architectural community.

In addition to buildings, she also designed jewelry, yachts and even a jelly shoe.

“I never use the issue about being a woman architect,” she told the Guardian in 2004, “but if it helps younger people to know they can break through the glass ceiling, I don’t mind that.”

The focus on her storied career in the wake of her death shows how much it is possible for a woman to achieve — and how much more ground women have yet left to cover.

A report published by the San Francisco Chapter of the American Institute of Architects last year revealed that though women make up 42% of graduates from programs accredited by the National Architecture Accrediting Board, they make up only 28% of architectural staff in AIA-member-owned firms, and only 17% of principals and partners.

In addition, a study released this year by the national AIA shows that women and minorities in the United States, two groups underrepresented in architecture, both cite a lack of role models as one of the major reasons the profession remains largely male and white.

The women who do labor in these environments have had to contend with dismissive or downright hostile behavior. In an interview I conducted with architect Denise Scott Brown in 2013, she described everything from direct insults to not being invited to architect parties because she was the “wife.” (She ran a firm with her husband, Pritzker Prize-winning architect Robert Venturi.)

Zaha Hadid stands before her design for the Serpentine Sackler Gallery in London in 2013.

Hadid, who was based in London, had to deal with some bad behavior herself. Anissa Helou, a cookbook author, teacher and chef, was a longtime friend of the architect’s. The two met in the early 1970s, at a dinner party hosted by a mutual friend.

“Being a strong woman and a foreigner in London in a man’s field [at the time] did not make it easy for her,” she stated via email. “Also, being so ahead of her time in her thinking and designs and being so uncompromising about what she wanted to do did not help, so she had to contend with a lot.”

When Hadid accepted the Royal Gold Medal earlier this year, she said in her remarks: “We now see more established female architects all the time. That doesn’t mean it’s easy.”

Moreover, there was the issue of her Iraqi heritage, which wasn’t always well-received.

“It’s a triple whammy,” she told the BBC Radio 4 in February. “I’m a woman, which is a problem to many people. I’m a foreigner — another problem. And I do work which is not normative, which is not what they expect. Together, it becomes difficult.”

Zaha Hadid designed the sets for a 2014 production of “Cosi fan Tutte” at Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles.

In the mid-1990s, Hadid won a competition to design a new opera house in Cardiff, Wales. As concerns about the purpose of the building and its budget hit the press, xenophobic remarks began to surface. One Welsh minister of parliament said that her geometric design was identical to the shrine in Mecca.

“It was disgusting the way I was treated,” Hadid told the New Yorker in 2009. “These British women would tell little jokes. ... It was awful. ‘We don’t want a fatwa! Tee-hee!’”

“There were people,” she added, “who wouldn’t look me in the eye.”

Like any high-profile architect, Hadid was expected to produce strong, functional designs. But as a woman, she also faced the added pressure of having her work interpreted as some sort of gender statement. One of her designs for a stadium was compared to female genitalia in the press — something she described as “nonsense.”

“You are vulnerable as a woman because there is pressure for what you represent not just for the profession, but in society,” said Annabelle Selldorf, principal of Selldorf Architects in New York. “She didn’t marry. She didn’t have a family. She didn’t represent the conventional model.”

Zaha Hadid designed the opera house in Guangzhou, China.

Hadid also wasn’t the sort of woman who stood around meekly asking for permission to join in, something that made her a significant example to other women.

“She was a big deal for women in architecture and not because she made that her thing,” said Selldorf. “But because she was simply a powerful person. ... She was so unequivocal and so powerful. That’s what made her an idol.”

Her toughness, however, was also used against her. Hadid’s imperious manner — directed at architectural selection committees as well as magazine writers and her staff — often got her characterized as a shrew by the press. In fact, much has been made of her “diva” behavior, even in her obituaries.

As Guardian critic Oliver Wainwright noted in an essay last fall, petulant male architects get described with words such as “maverick” instead. When the irascible Philip Johnson died in 2005, the New York Times referred to him as an “enfant terrible,” a label that comes off as charming and continental.

Certainly, there are aspects to Hadid’s career that are unsavory — such as her work in locations where serious human rights issues have come up (such as the cultural center she designed in Azerbaijan). It’s important, though, to note that in this regard she was no different from some of her male starchitect colleagues — figures such as Norman Foster and Rem Koolhaas, who have taken on morally questionable assignments in locations such as Kazakhstan and China, respectively.

But whatever the ramifications of individual buildings, the fact is that Hadid’s death leaves an enormous void. She remains the only individual woman to have won the Pritzker in its nearly 40-year history, and the only woman to have won the Royal Gold Medal in its 168-year history. On so many occasions, she has been the lone female architect in the room — and with her absence, some of those rooms may revert back to being all male.

Women have made tremendous gains in architecture since Hadid launched her career in the 1970s. They build towers and design museums and magazine-worthy weekend homes. But they still remain sorely underrepresented.

Hadid’s death has prematurely taken a powerful emblem from our midst, a woman who commanded respect and prestige — and who didn’t feel the need to be all cuddly about it.

“I just do what I do and that’s it,” she told the BBC nonchalantly back in February.

As far as a whole generation of women architects are concerned, however, what she did was just the beginning.

Twitter: @cmonstah

MORE:

Architect Zaha Hadid becomes first woman to win Pritzker Prize

A mix of the urban and urbane: Zaha Hadid’s remarkable Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center

Zaha Hadid’s garden spot in Germany has city smarts

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.