L.A.’s museum district is rebuilding. But they’re ignoring pedestrians (again)

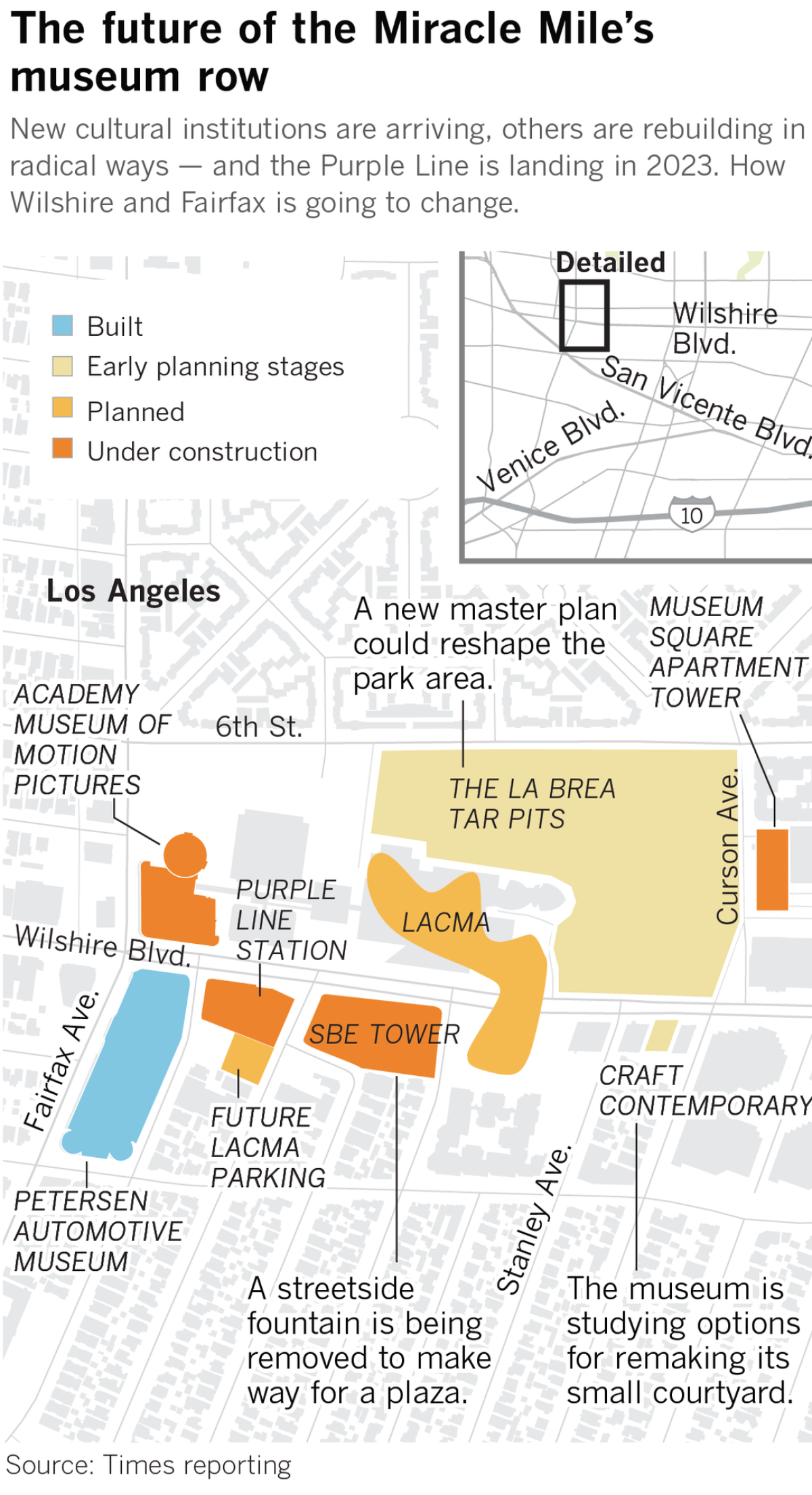

In the near future, some time in 2023, Metro’s Purple Line will disembark its first passengers at a station across the street from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Renzo Piano-designed BCAM building. Those passengers will emerge onto Wilshire Boulevard to find a Los Angeles that has been largely remade.

On the northeast corner of Wilshire and Fairfax, across from the Petersen Automotive Museum, will be another Piano design, the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, which has undergone numerous delays (the latest targeted opening is sometime in 2020) but is well under construction. Harbored to the northern façade of the remade May Co. department store building that will house most of the film museum will be a spherical 1,000-seat theater, inspired by the dirigibles that used to land on early 20th century air fields in the area.

For the record:

2:40 p.m. July 12, 2019An earlier version of this story reported that Curson was west of Fairfax. It is to the east. In addition, Doug Suisman’s master plan for the Hancock Park area was developed five years ago, not three.

To the east, if all goes according to plan, will be the new LACMA, designed by Peter Zumthor, which will not only rise off the ground on pilotis, it will reach south across Wilshire, creating a bridge over the boulevard. Across a side street from the Metro station, a new sidewalk plaza at 5900 Wilshire, the 32-story tower that bears the SBE logo, will offer pedestrians a place to sit and gather.

Further east likely will be the fruits of design processes that are just beginning to take hold. Last month, the La Brea tar pits announced a new master plan. And the Craft Contemporary museum is in the earliest stages of revamping its courtyard, an outdoor space that faces Wilshire and could one day function as a public gathering and exhibition space.

These projects mark a reinvention for the western edge of the Miracle Mile, the early 20th century commercial strip that by the 1980s had sputtered economically but has since evolved into one of the city’s most important cultural hubs.

“It’s making the Miracle Mile a miracle again,” says Terry Karges, executive director of the Petersen Automotive Museum, which has inhabited the refurbished Ohrbach’s department store building on the southeast corner of Wilshire and Fairfax since the 1990s.

But all of the development raises concerns about how the architectural pieces — and, more important, the public spaces around them — will come together after the last nail has been banged into place.

When developer A.W. Ross launched the idea of the Miracle Mile in the 1920s — a “linear downtown” that beckoned automobile drivers with lots of shopping and even more parking — the area was primarily zoned residential. Ross got around the rules by obtaining commercial spot-zoning exemptions on 18 acres of properties one by one. That story, to some degree, remains the story of how Los Angeles gets built: a combination of limited central planning and a pile of exceptions.

A century later, as new institutions land in the area, and old ones rebuild in dramatic ways, the big question is whether Los Angeles can pull it together to approach its public urban spaces in ways that are more cohesive and more mindful of human scale — and perhaps (just perhaps!) correct some of the errors of the past.

“We have this museum district,” says architect and theorist Dana Cuff, who oversees cityLAB, an urban research and design center at UCLA, “but the stuff that holds everything together is the part we call the city, and that is the part that Los Angeles has never gotten right.”

ALSO: The La Brea Tar Pits are getting a makeover. Here’s why »

Certainly, the current experience is — to be kind — underwhelming. Walk east on Wilshire from Fairfax to Curson Avenue, particularly on the south side of the boulevard, and you will find long stretches of sidewalk without shade and an insufficient number of street crossings. On the north side of Wilshire, Chris Burden’s “Urban Light” sculpture beckons crowds to the LACMA campus; on the south side, a barren sidewalk outside the Craft Contemporary museum sits empty. The museums are nice places to visit; the street, not so much.

Moreover, within Hancock Park (the park, not the neighborhood), where the Academy Museum, LACMA and the La Brea tar pits reside, the navigational experience is often circuitous. Even though they sit next to each other, LACMA offers few pathways to the tar pits, often requiring an awkward path that loops around to the north or a nearly two-block-long trudge along an uninspired stretch of Wilshire to the main gate at Curson. A gate just east of the museum, which could provide easier access, is frequently kept locked.

“There is no there there,” Cuff says. “There is no urban design that has been created for this chunk of Wilshire that will be one of the most pedestrian and populated parts of the city.”

In this city, the street is an afterthought, not a starting point.

— Doug Suisman, architect and author

The 2023 arrival of the yet-to-be-named Metro station raises the stakes on the urban experience. L.A. Metro estimates that 6,025 people will board or disembark from the station on a daily basis.

What will be waiting for them when they land? What is the urban plan?

Well, there isn’t one. At least not a grand civic master plan that will govern the public spaces around Hancock Park in considered ways.

Part of this has to do with the complexities of the site and the nature of bureaucracy in Los Angeles: Hancock Park sits on county land, while the street is managed by the city — and within the city, various agencies all have their hands in the dough.

“The domain of the street itself, the public right of way, it’s a multidepartmental domain,” notes Craig Weber, principal city planner at the Department of City Planning. “It’s fundamentally the Department of Public Works — they have multiple bureaus — and the Department of Transportation.”

DOT will be implementing new safety features in anticipation of Metro’s arrival, such as a zebra crosswalk over Orange Grove Avenue, on the south side of Wilshire, and wheelchair-accessible ramps on the current crossings at Wilshire and Ogden. But these improvements are only for existing crossings in the immediate vicinity of the station. No additional crossing points over Wilshire are planned.

This will make it harder for pedestrians to get around this burgeoning museum district. There will be no direct crossing over Wilshire between the Academy Museum and the Purple Line station. Likewise, there will be no direct crossing between LACMA and 5900 Wilshire (a popular food-truck spot), despite the fact that the properties sit across the street from each other. On the eastern end of the park, the Craft Contemporary will remained marooned — since no additional crossings over Wilshire are planned at Stanley Avenue.

If the idea is to encourage pedestrian activity, this non-plan is not the way to do it.

ALSO: An open letter to LACMA architect Peter Zumthor: Stop dissing L.A.’s art »

Moreover, to add amenities such as shade trees and street furniture, the city needs to set aside funds in the capital improvements budget. “That has been a difficult thing for the city for many years,” says Weber. “The city has had to get really creative with funding mechanisms.”

Some of these issues likely will come up for discussion when the Wilshire Community Plan goes up for review, but that likely won’t be for another two years. By then, one of the biggest projects of the bunch — Zumthor’s behemoth 348,000-square-foot LACMA building — could already be under construction.

In the meantime, each institution is left to manage its own street frontage.

“In this city, the street is an afterthought, not a starting point,” says architect Doug Suisman, who is also the author of “Los Angeles Boulevard: Eight X-Rays of the Body Politic,” which tracks the histories of important L.A. boulevards such as Wilshire. “We are putting new stuff along the street and we are putting a big new thing over the street, but the street itself? Maybe it will get some cosmetic improvements after the fact.”

With each institution managing its portion of the street, the city becomes reliant on the various entities along Wilshire to come together to produce something akin to an urban experience. Already, the track record is mixed.

Five years ago, Suisman, who is founder of the design and urban planning firm Suisman Urban Design, worked on some interim wayfinding and other improvements at the La Brea tar pits. Separately, he began work on a preliminary master plan for Hancock Park and Wilshire Boulevard that methodically addressed some of the area’s urban problems. But the plan stalled and was never completed or released.

The Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County, which manages the tar pits, did not respond to a query on the matter. But it’s not out of the realm of possibility that the continuous shapeshifting of LACMA’s proposed Zumthor building has made it difficult to do any kind of long-term planning.

This raises the issue of coordination — or lack thereof — between the institutions on Miracle Mile.

In 2013, when Zumthor released the initial schematics for the new LACMA building, the design featured a dramatic cantilevered wing that hung over the La Brea tar pits. The following year, he was forced to revise the design over environmental concerns.

“We wrote a love letter to the tar pits, but they didn’t love us back,” says LACMA director Michael Govan.

It was a letter that was delivered without any advance courting.

“When the initial design for the Zumthor building at LACMA was presented six years ago, there had been no prior consultation with the Natural History Museums of Los Angeles, which oversees La Brea tar pits,” president and director Lori Bettison-Varga says in an email.

That has since changed, and staff from LACMA and the La Brea tar pits get together for regular meetings with architects from Zumthor’s office. In fact, senior staff from the various museums regularly meet to coordinate on construction and other group initiatives, such as a current summer promotion that offers a $2 discount to visitors who show a ticket from another Miracle Mile museum. But I couldn’t get an answer on when the leaders of all five institutions — the Petersen, Academy Museum, LACMA, the La Brea tar pits and the Craft Contemporary — last got together in a room.

ALSO: In a new redesign LACMA experiences shrinkage — and shapeshifts yet again »

Given the nature of this process, what likely will result in the neighborhood is a mixed bag of urbanism.

At the Academy Museum, Piano’s architects have taken great pains to keep A.C. Martin & Associates’s graceful May Company building from the 1930s largely intact and easily accessible to pedestrians arriving from all directions. They are maintaining the building’s original parallel entrances (one on Wilshire and one on the north side of the building), which will allow the first-floor lobby to function as a public space, with a restaurant and a shop. They also are removing the backing from the streetside display windows to allow for greater transparency.

“It will be a place for people to come and gather — under the sphere, inside the large lobby, to see a film or take in an exhibition,” says the museum’s director, Kerry Brougher. “We really want it to be a meeting place for people.”

How hospitable it will feel to sit under a gargantuan sphere remains to be seen. (The whole area is shaping up to be relentlessly macho — with Piano’s giant ball, Michael Heizer’s massive rock and Zumthor’s very colossal crooked thingy.)

Across Wilshire, the 2015 gut and remodel of the Petersen Automotive Museum — a 1960s department store by Welton Becket that features a flaming spaghetti façade by New York architects Kohn Pedersen Fox — has helped increase attendance from 125,000 visitors to 400,000 per year. “People drove by it for 20 years,” says Karges. “Now you can hardly not look.”

But on the level of urbanism, the building remains standoffish. The ribbons of steel that serve as façade obscure from public view the museum’s entrance — as well as the public spaces within. This includes a public passageway that leads to the parking garage and a sidewalk restaurant, Drago, that faces Fairfax (and has a darn good happy hour). This is prime real estate for a restaurant — good luck catching a glimpse of it.

Now the big question is what LACMA will add to the urban mix.

The elevated design, Govan notes, will make all of Hancock Park more easily accessible.

“That’s something Peter really worked on,” he says, “was to bring back the park.”

But question marks still hover over countless elements. No final renderings for the landscape design (which is being handled by Olin, a firm with offices in Philadelphia and Los Angeles) have been released. Plus, there have been no schematics that detail what the underside of Zumthor’s elevated museum building will look like — whether it will evoke a cool cave or a grim parking structure. And there’s the question of bridging the museum over Wilshire, a move that could have the effect of making the area seem less welcoming rather than more.

“The bridging says, ‘We are going to remove pedestrians from the street and make it easy for cars to move through here at high speed,’” says Suisman. “It feels anti-street.”

How all of this will register from the sidewalk is also still up in the air.

Govan says that Los Angeles, to some degree, owes its singular look and its architectural innovations to the somewhat chaotic planning process.

“The more I live in L.A., the more I appreciate the diversity of the environment and not having formal architectural frameworks of super master plans like Brasilia or the National Mall,” he says. “L.A. has a history of that. The colors that don’t match. The buildings that don’t always go together.”

That L.A. has its charm. But that charm can wear thin. It is an L.A. built by individuals for their own ends. It is an L.A. that favors the car over people. It is an L.A. that treats public space as an afterthought. And as the city grows bigger and denser, it may just be time for that L.A. to evolve.

ALSO: L.A. has a terrible track record on land-use rules. Is that about to finally change? »

[email protected] | Twitter: @cmonstah

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.