How Mexico’s <i>súper rudas</i> ‘Radical Women’ are rewriting the history of Latin American art

They are women who turned stories of sexual assault into installation art. They made drawings that gave sexuality a distinctly feminine point of view. They delivered art history lectures wearing aprons and crafted a quinceañera gown out of beef — years before Lady Gaga was even a glint in her parents’ eyes. And they helped transform the face of art over the span of a continent.

They are women — some well known in Latin American art circles, others far less so — who will collectively get their due at the Hammer Museum’s “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985,” one of dozens of Southern California exhibitions to open this fall as part of Pacific Standard Time: Los Angeles / Latin America. No other PST: LA/LA exhibition promises to rewrite history quite like “Radical Women,” which documents the transformative work of U.S. Latinas and Latin American women artists who have all too often been ignored by major art institutions.

“I never set out to be a radical artist,” says Maris Bustamante, a pioneering conceptual artist from Mexico City, who among her various playful actions patented the taco and created a face mask with a phallus for a nose as a wry comment on Freud’s concept of penis envy. “It was the context that shaped us.”

That context was the Latin America of the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s — a turbulent period beginning just seven years after women in Mexico were granted the right to vote in national elections in 1953. It was an era when painting ruled — and men ruled painting.

We are doing this show because 50 years have gone by and the percentages of the representation of women in galleries and museums ... is still 30%.

— Andrea Giunta, co-curator, 'Radical Women'

Indeed, when the 1975

Magali Lara, a Cuernavaca-based artist known for her intimate assemblages, was a student at the Academy of

“We used to have these discussions which today would be considered absolutely ridiculous but back then were very serious,” she recalls. “We’d talk about whether women could or couldn’t be painters because of our maternal qualities, and how women were good students but not good creators. This idea that we were very docile and easily influenced — that’s how they treated us.”

The “Radical Women” exhibition spans the Americas, from Los Angeles Chicana artists contending with issues of marginalization to women in Chile, Brazil and Argentina who were facing the extreme repression of their respective dictatorships.

“These were women dealing with power,” says the show’s co-curator, Cecilia Fajardo-Hill. “They are women fighting power.”

“We are doing this show because 50 years have gone by and the percentages of the representations of women in galleries and museums, in the best cases, is still hovering at 30%,” says co-curator Andrea Giunta. “And that’s in the present. Think of the artists who have been completely erased and remain completely outside of the institutional gaze.”

What is now elegantly referred to as ‘intersectionality,’ we were discussing it in Mexico back then.

— Mónica Mayer, artist

Of particular note are the artists who worked in Mexico during the 25-year period examined in the exhibition.

This includes Bustamante, as well as the influential Mónica Mayer, whose installation work, “El Tendedero” [The Clothesline], first created in 1978, and re-created in Los Angeles in 1979, became an impromptu rumination on the prevalence of sexual assault.

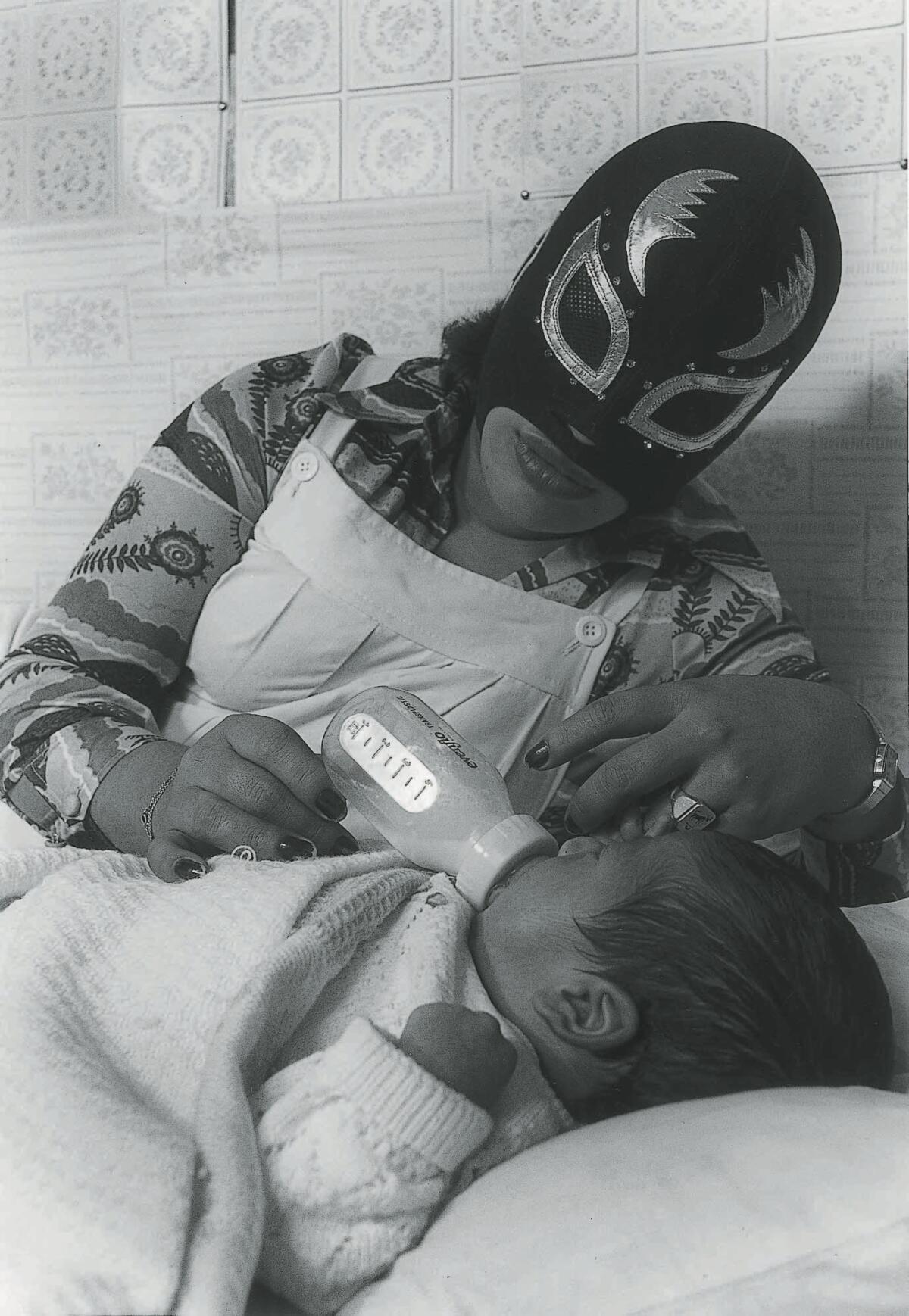

There are artists like Carla Rippey and Lara, with their frank takes on female sexuality. And there are photographers such as Ana Victoria Jiménez and Lourdes Grobet, each addressing the realities of Mexico in her own ways: Jiménez, by recording the mundane actions of domestic labor, Grobet through a now well-known series that documents Mexican wrestlers.

Mexico, quite significantly, was the only Latin American country to have a feminist art movement that could compare with those of Europe or the United States.

“Mexico has had a feminist movement since the 19th century — and a very visible one,” says Karen Cordero, a feminist art historian who has contributed an essay on the subject for the exhibition’s catalog. “The first feminist congress in Mexico took place in 1916, in Yucatán, and since then there has been visibility for feminism in Mexico.”

Art out of repression

The years in which the artists of the “Radical Women” generation came of age were marked by nationalistic isolation, brutal dictatorship and guerrilla insurgency. In 1968, the country was convulsed when the Mexican military massacred an unknown number of students in Tlatelolco who were protesting government expenditures on that year’s Olympic Games. What followed was a social and political clampdown.

Out of that repression came artists creating wildly experimental works of photography, assemblage, installation and performance, all while tackling complex issues of race, class, gender, sexuality and domesticity.

The 1970s saw a rise of artists working in collectives known as los grupos [the groups], a phenomenon that emerged in the wake of the student organizing behind the Tlatelolco protests. Many of the Mexican artists in “Radical Women” participated in grupos — with men and with other women.

“It was the ‘70s, the era of dictatorships,” says Rippey. “There was a whole political thing — the issue of repression was very present. The grupos were a reaction to that.”

Progress came in a series of steps forward and back. At the 1975 U.N. World Conference on Women, when the Museo de Arte Moderno produced the clumsy tribute to women, the museum also put together a colloquium that brought together women from disparate fields — artists, historians, anthropologists.

“We talked about class, we talked about race, we talked about craft, about the difference between art and craft,” Mayer recalls. “What is now elegantly referred to as ‘intersectionality,’ we were discussing it in Mexico back then.”

In the early 1980s, Mayer teamed with Bustamante to launch Polvo de Gallina Negra, a feminist art collective. The pair gave humorous performance-lectures about women and art while wearing frilly aprons.

“People always said, ‘Women in the kitchen,’” Bustamante says, laughing. “So we would come from the proverbial kitchen to the stage.”

In one performance, they appeared on “Nuestro Mundo,” a national television program hosted by journalist Guillermo Ochoa — decked out in aprons and prop pregnant bellies — and persuaded Ochoa to don a similar outfit.

Súper rudas

In the mid-1980s, Mayer, with the women’s collective Tlacuilas y Retrateras, organized a series of happenings at the Academy of San Carlos that examined the tradition of the quinceañera, the 15th birthday celebration that serves as a coming-of-age ritual for girls across Latin America.

For that event, one artist showed up in a gown crafted from steak. Another wore a chastity belt.

“It was very critical of the whole tradition,” says feminist art historian Julia Antivilo Peña. “It got a lot of coverage in the press, including critical coverage. And it was one of the happenings that helped serve as a point of consolidation for the feminist art movement in Mexico.”

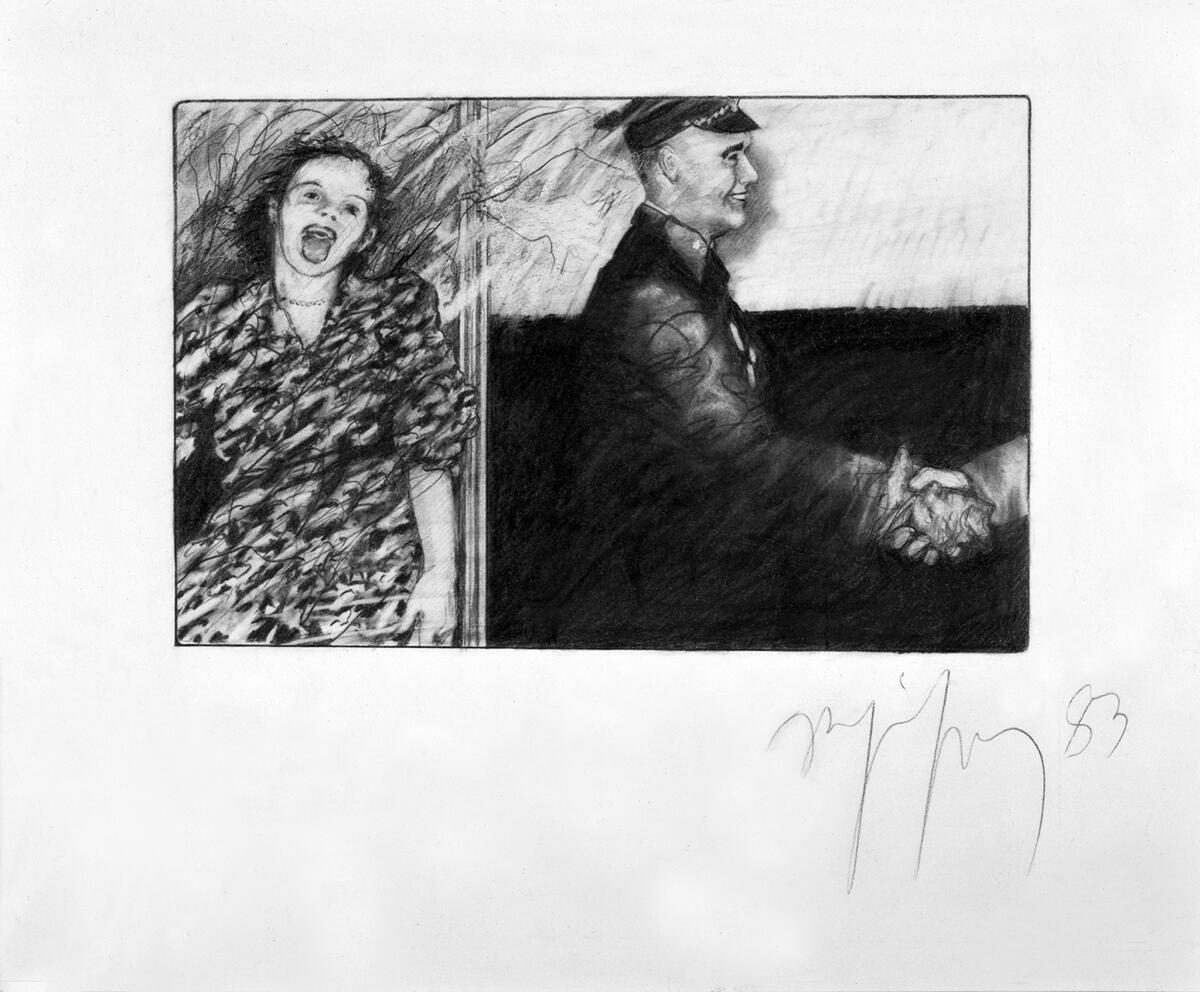

Another artist who challenged the ways in which gender was presented is Rippey, who now serves as director of the National School of Painting, Sculpture and Engraving, known as La Esmeralda. “I worked a lot with the female nude,” she says. “I would take images of Victorian soft-core porn but try to re-imagine them from the point of view of the woman — of the pleasure they felt.”

Lara, likewise, played with eroticism, in more obtuse ways involving language and symbols.

“They called us las despeinadas,” she recalls, using a term that describes women with messy hair. “We were súper rudas” [very indecorous].

If the women of the era helped expand the issues addressed in Mexican art, they also helped challenge the materials from which it was made. There was drawing, installation, performance and fusions of all of the above.

Jiménez and Grobet worked in photography — at a time when the medium commanded little critical respect. For an early show in 1970, Grobet employed pictures as part of a room-size installation.

“I was trying to take photography out of its context,” she recalls. “It was a labyrinth made entirely out of photomurals — and the whole idea is that you were opening up the figure of man. It was the ’70s and the whole psychedelia thing was happening, so I was using projections and psychedelic effects and figurines that moved … and you ended up in a room full of mirrors with this infinite view of yourself.”

But as figures who pushed boundaries, many women artists found themselves operating in a no man’s land — or more, accurately, a no woman’s land — between feminism, art and politics.

The mainstream Mexican art world didn’t give their work much air time. But neither did the feminist movement. (The country’s theoretical feminists often looked askance at art actions involving nudity, for example.) Not to mention that not all artists were comfortable with the feminist label.

Says Grobet: “I always felt as if it was imported from Europe or the United States.”

We’d talk about whether women could or couldn’t be painters because of our maternal qualities ... that's how they treated us.

— Magali Lara, artist

!["Ventanas," [Windows], 1977-78, by Magali Lara. (Acervo Museo de Arte Moderno / INBA, Mexico City)](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/e21e2b6/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1884x2048+0+0/resize/1200x1304!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F1f%2F06%2F9287db3b444621efa581857b9d86%2Fla-1503947548-runwsgmwv8-snap-image)

In the meantime, the left, with which many artists were politically aligned, questioned the idea of a need for a separate women’s movement at all.

“The argument on the left was that when the revolution happens, woman will have the place she will have,” Giunta explains, “justice will be for all.”

But leftist views didn’t always jibe with women’s concerns. A favorite leftist hymn of the era began with the command, “A parir madres Latinas, a parir más guerrilleros” [Latin American mothers, time to give birth / to birth more guerrilla fighters].

“‘A parir madres,’ frankly, used to make my hair stand on end,” Jiménez says. “You are fighting for independence, for the liberation of women, for a dignified life — and someone comes along to tell us that if we’re not good at making babies, then you don’t count. Those concepts from the ’70s, to me, were really problematic.”

What the “Radical Women” exhibition at the Hammer promises to do is take these artists out from that in-between space and consider their work on its own terms — in a way that dovetails quite perfectly with our politically minded moment.

You are fighting for ... a dignified life — and someone comes along to tell us that if we’re not good at making babies, then you don't count.

— Ana Victoria Jiménez, artist

Moreover, the exhibition’s focus — on the ways in which women employ the body — is especially current given ongoing debates about violence against women, from the casual talk by a U.S. presidential candidate of sexual assault to the killing of women in Mexico, which has reached epic proportions.

“The show will be important in a lot of ways,” Cordero says. “But one will be to show the ways in which art can be a tool of resistance — which was the case for a lot of the art that will be present in the show.”

“If this show was important a few months ago, it becomes even more so now,” Mayer says. “It acquires a political framework that is much more defined — because we are women and because we are Latin American.”

“Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985”

Part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA

Where: Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood

When: Sept. 15 to Dec. 31. Closed Mondays.

Info: (310) 443-7000, hammer.ucla.edu, pacificstandardtime.org

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

Hammer Museum's 'Radical Women' to showcase Latina artists on the politics of the female body

Mexico City's art scene is booming, but even with deep roots, political uncertainty keeps it fragile

Argentine slums and a Unabomber cabin: How 'Home' at LACMA rethinks ideas about Latin American art

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.