With raw eggs and a roomful of clay, Anna Maria Maiolino makes unsentimental art about being a woman

Brazilian artist Anna Maria Maiolino is the subject of a one-woman retrospective at MOCA, her first in the U.S. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

The performance begins with raw eggs. Dozens of them, scattered in their fragile shells all over the sculpture plaza adjacent to the Museum of Contemporary Art in downtown Los Angeles.

The audience gathers around them. Out of the crowd emerges a petite woman with fine features and white, closely cropped hair. She studiously arranges the onlookers with a series of hand signals. Moving them in closer, setting them back, gesturing for the seated to stand.

Artist Anna Maria Maiolino first staged this performance in 1981 in a cobblestone street in São Paulo, Brazil, where she walked barefoot through a minefield of raw eggs with her eyes closed. The piece, titled “Entrevidas,” came at a charged period in her country’s history: toward the end of a brutal military dictatorship that had quelled free speech and resulted in disappearances and other human rights abuses.

“There is the saying ‘like walking on eggshells,’ ” explains Maiolino. “In that moment, we didn’t know if the country would open up or if it would close itself off.”

It was a perfect metaphor for that political time: Each step forward, however gingerly taken, held with it the possibility of great destruction.

The performance of “Entrevidas” at MOCA, held in mid-September during the official launch of the Pacific Standard Time: LA / LA series of exhibitions, is more joyous. But not without moments of tension.

After Maiolino arranges the crowd to her liking, a young man materializes to one side of the eggs. The artist, now 75, has enlisted her grandson, actor Gabriel Sitchin, to perform.

Sitchin closes his eyes and sets a foot between a pair of eggs. Then he draws another foot into the egg maze, and another, using his toes to grope the ground before him in his temporary blindness. The crowd, previously engaged in raucous conversation, grows silent. The only soundtrack is the hum of industrial air conditioners.

At one point, Sitchin’s heel comes dangerously close to crushing an egg and Maiolino gasps. A little girl exclaims, “Yes! Yes! Yes!” Sitchin moves his foot and the egg survives. The crowd exhales.

The actor eventually comes to rest on one side of the maze. He opens his eyes and the crowd erupts into applause. Grandmother and grandson smile and exchange knowing looks. In the dying light, the eggs take on an otherworldly glow.

For much of her long career, Maiolino has been little known in the United States. But as of late, her profile has grown.

She is the subject of a one-woman retrospective at the MOCA on Grand Avenue, her first in the U.S. And her work makes an appearance in a pair of high-profile group shows: “Radical Women,” which focuses on avant-garde Latin American women artists at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, and “Delirious,” a newly opened exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art that examines the ways in which 20th century artists responded to overbearing political systems with work that was often surreal and absurd.

A conceptual artist whose multimedia work frequently explores issues of repression and yearning, Maiolino is generally identified as Brazilian. But like many Brazilians, her heritage spans continents.

The artist was born in Italy during World War II to an Italian father and an Ecuadorean mother. When she was 12, the family emigrated to Venezuela. Six years later, they relocated to Brazil. In the late 1960s, she became a Brazilian citizen.

I get a materiality when I come into contact with clay. … Tierra modelada — that’s what it is to me: shaped earth.

— Anna Maria Maiolino, artist

Seated in MOCA’s Grand Avenue galleries over the summer, where she was installing the ongoing retrospective that bears her name, she conducts our interview in Spanish — one that bears musical lilts of Italian and Portuguese.

“I had the ear for Spanish,” Maiolino says. “My aunts and my mother spoke it a lot. They spoke it when they didn’t want us to understand what they were saying.”

Maiolino’s art, like her origins, is also hybrid.

“My work developed in Brazil,” she says. “People consider me as being Brazilian. But it has many layers, like an onion.”

The eye-grabber at her MOCA retrospective is a gallery filled with pieces of unfired clay: a wall covered in squashed blobs, giant piles of spaghetti-like viscera in mounds on the floor, a table filled with lumpy protuberances and intestinal forms — as if a massive clay body has come apart and its myriad parts put on display.

On the day we meet at the museum, MOCA’s pristine white box has been transformed into a raucous ceramics studio. The room is filled with the fragrance of damp earth. Maiolino, decked out in a stained apron, stands at its center — shaping, molding, coaxing form out of inert blocks.

“They feed me,” she says, gesturing to the clay around her. “I get a materiality when I come into contact with clay. … Tierra modelada — that’s what it is to me: shaped earth. The viewers, if they are sensitive, as many are, they will find in this accumulation of work, their own work, the gestures they repeat daily.”

In 2012 as part of Documenta 13, the every-five-years exhibition held in Kassel, Germany, the artist filled every available surface in a former gardener’s home with her unfired clay forms.

MOCA curator Helen Molesworth, who helped organize Maiolino’s Los Angeles retrospective with researcher Bryan Barcena, recalls being bowled over by the installation.

“Clay is one of the most rudimentary mediums, yet it’s also the beginning of civilization,” she says. “Any monkey can make a finger pot, but you can’t have civilization without pottery. She’s always in this place where you can’t privilege one side over another side.”

But Maiolino’s work is about much more than clay — and the basic gestures and bodily functions it might convey.

A woman is never the universal. When I put the word ‘eu,’ that was when I decided what I would be. It was a determination.

— Anna Maria Maiolino, artist

Over the course of a career more than five decades long, the artist has employed a wide variety of media — printing, photography, performance, video and sculpture — to explore, in ways both muted and visceral, her place in the world as woman, as citizen, as a human body filled with the pangs of hunger, both physical and psychological.

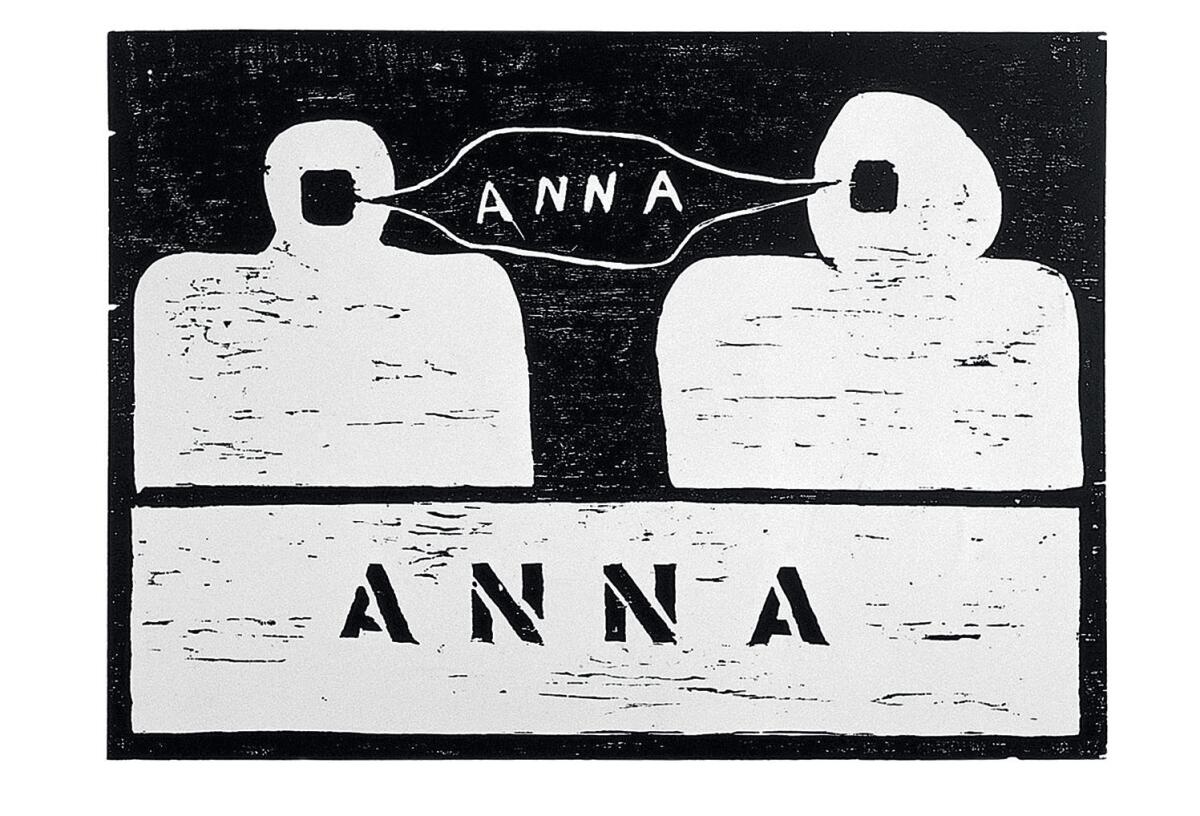

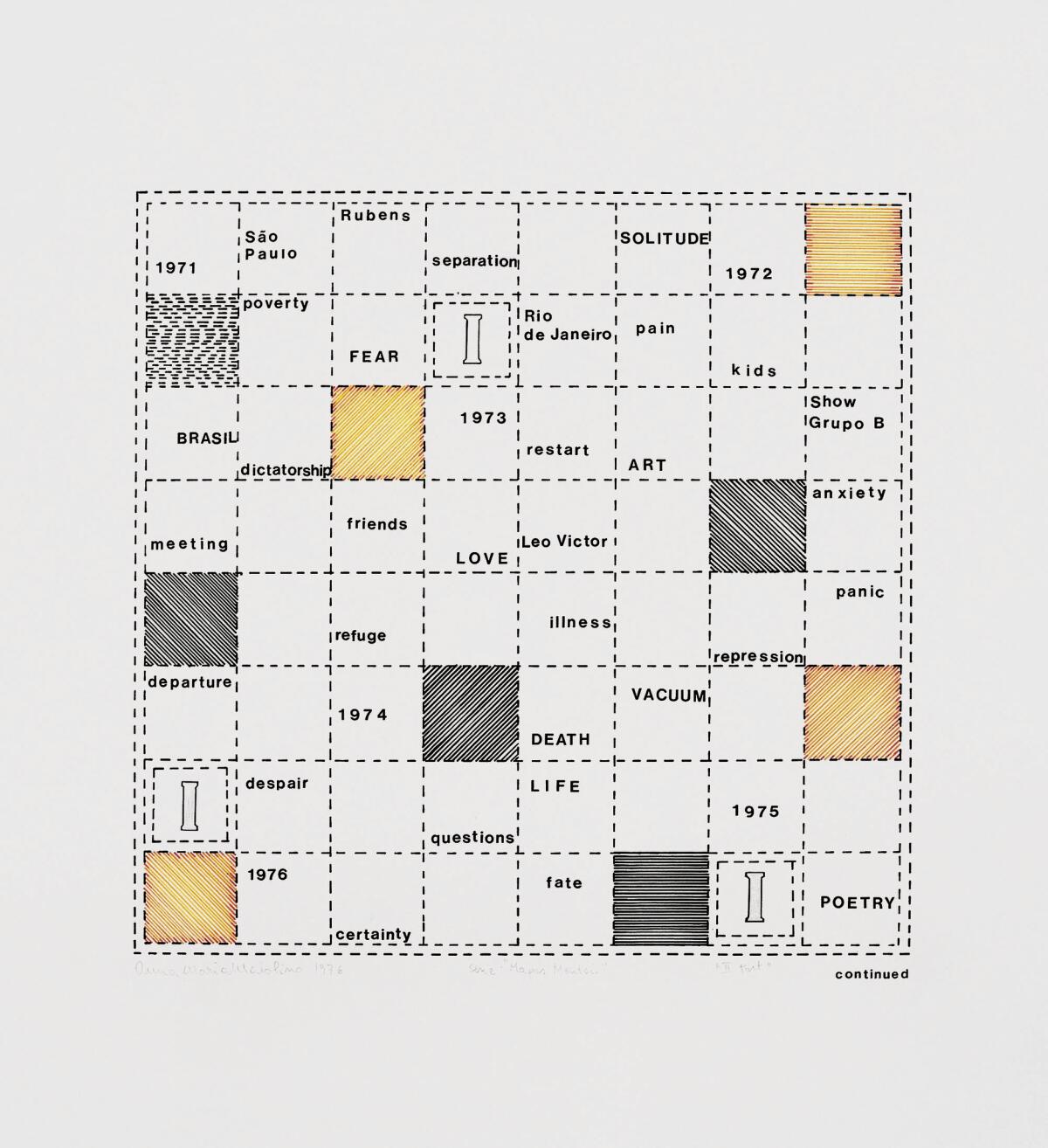

Some of her early pieces allude to issues of gender. “A Espera,” an assemblage from 1967, shows the silhouette of a woman hovering over a line of laundry bearing children’s clothes. Others map, in diagrammatic ways, elements of her life. One piece titled “Eu” from 1971 — “eu” is Portuguese for “I” — repeats the word at different angles over the course of a grid.

“Much of my work has has to do with mental state, with my biological state as a woman,” Maiolino says.

“Women have always been prohibited from speaking in the first person,” she adds. “A woman is never the universal. When I put the word ‘eu,’ that was when I decided what I would be. It was a determination.”

Other works address the coercive politics of Brazil’s military regime. (Maiolino’s developmental years paralleled the dictatorship, which lasted more than two decades, from 1964 to 1985.) In a photo installation from 1974 on view at both MOCA and the Hammer, she depicts herself wielding a pair of scissors, about to cut off her nose and her tongue.

“That was a reaction,” she says. “There was such great repression: Just cut my tongue, poke out my eyes because I can do nothing.”

Maiolino’s unusual path can be traced to her teenage years in Venezuela.

Like many a young woman in Caracas in those days, she was dispatched to secretarial school by her parents. The school was located in an old colonial building. But instead of studying dictation, Maiolino would often sneak into an upstairs hall that offered art classes.

“It was this beautiful classroom and a nun taught drawing and she had these vases full of roses,” she recalls. “My parents were so crazy they didn’t notice that I never got a secretarial degree.”

As an immigrant in Venezuela, she had always felt hampered by her foreignness and her imperfect Spanish. But with drawing, she could speak freely.

“I was reconstituting my identity, my ego,” she says. “I started to recuperate myself.”

But just as she was settling into the rhythms of life there, the family relocated — this time to Brazil. In 1960, at the age of 18, she was once again the outsider, starting in a new language and landscape all over again.

Enrolling in university was complicated by her language skills. So Maiolino decided to audit classes instead — at the Escola Nacional de Belas Artes, the national fine art school in Rio de Janeiro. It was there that she met painter Rubens Gerchman. They soon married and had two children.

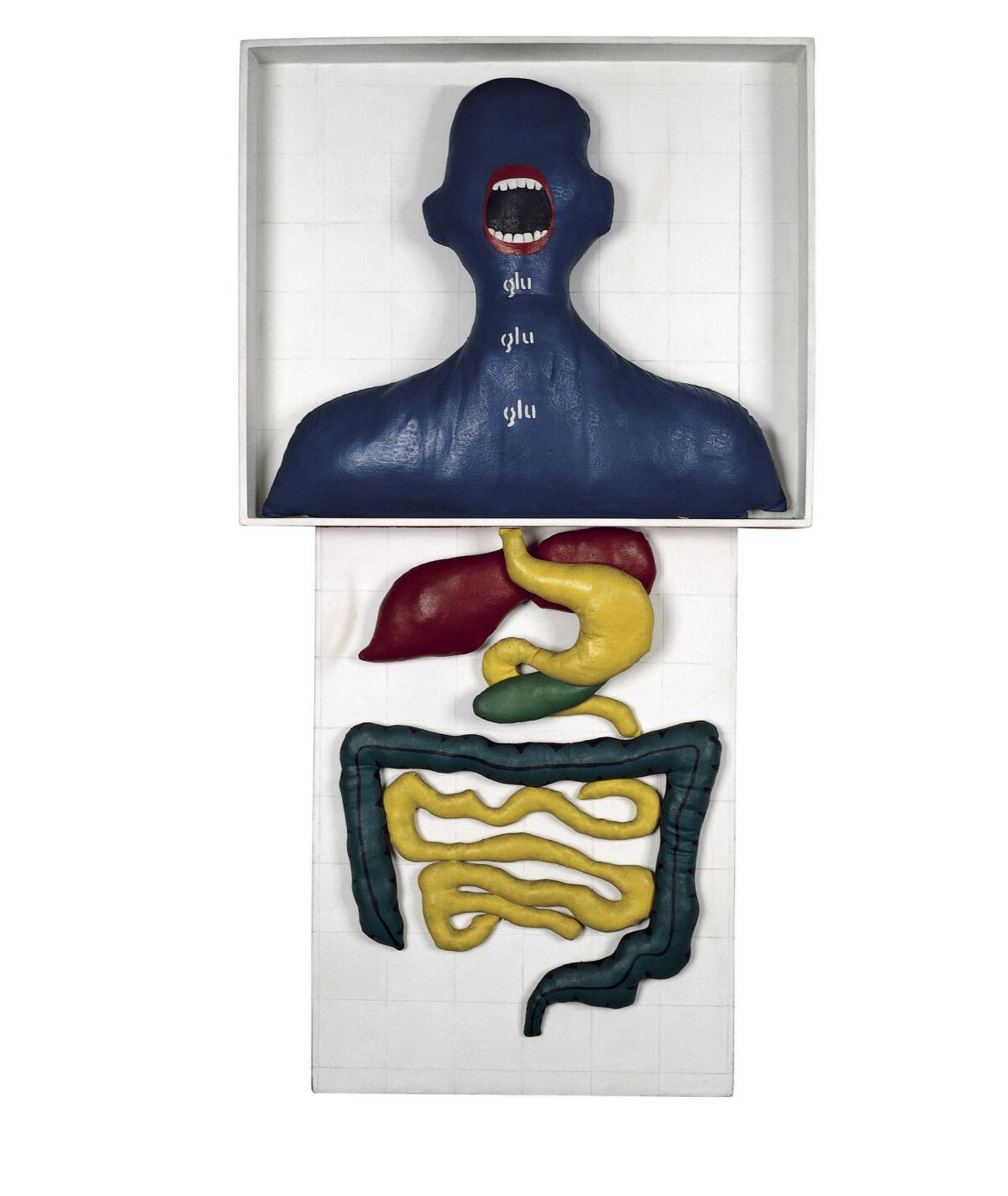

During these early years as an artist, Maiolino produced drawings, assemblages and woodblock prints that began to establish themes she was interested in: images that mapped her place in society, as well as abstracted figures frequently depicted with an open mouth. In the assemblage “Glu Glu Glu,” from 1967, for example, a head attached to a human digestive system seems ready to devour everything in sight.

“The mouth stuff is interesting because she is a migrant,” Molesworth says. “Her mouth has to eat new food and say new words. The profundity of culture being linked to food and language has real truth.”

In 1968, Maiolino and Gerchman moved to New York temporarily after Gerchman was awarded a fellowship. It was a way to escape the repressiveness of Brazil — “like a self-exile,” she says.

In those years, she was more devoted to practical concerns: her husband and her children. She also worked illegally as a fabric designer. “If they wanted pineapples, I’d make pineapples,” she said. “I never signed my designs because I never wanted to be a fabric designer. It was just a way to make money.”

Upon her return to Brazil, she divorced Gerchman. “And I decided that I would be a mother and artist with the same importance,” she says.

The ’70s happened to be a period of wild experimentation. Artists were working in performance, video and ephemeral installation, and Maiolino dove right in. She made surreal Super 8 films, such as “In-Out (Antropofagia)” from 1973, in which mouths chew objects, say words and birth an egg. She also staged actions, such as the egg field of “Entrevidas.” (Eggs, a symbol of fragility and fecundity, make regular appearances in her work.)

In the ‘80s, she married for a second time — to conceptual artist Victor Grippo. But that union ended in divorce in 1989. Afterward, Maiolino says she made a decision to dedicate herself fully to her work.

“I lived on $200 a month and I paid basic expenses, but that was it,” she says. “My friends would call me to go out and I’d make things up. Everything — the taxi, the beer, you have to earn it. I wanted to have a chance not to worry. That was when I started using cement because it was very cheap, then clay.”

That austerity led to an artistic flowering that continues to this day.

When you are 25 or 28, you want to belong. But then you learn that identity mutates. You have a lot of identities and they change over time.

— Anna Maria Maiolino, artist

Part of what has made her stand out is the range of media she uses, but also the pragmatic ways in which she has approached womanhood in her work.

“She is not sentimental,” Molesworth says. “She recognizes: Human beings, they fornicate. Half of them could be made pregnant. There are babies and they need to be fed and cared for. The survival of the species is this modus operandi that exceeds all of us.”

Maiolino says she has come to terms with the feeling of being the perennial outsider.

“When you are 25 or 28, you want to belong,” she says. “But then you learn that identity mutates. You have a lot of identities and they change over time.

“I arrive at what I have through experience. Art gives you that experience. That is art — it enriches you.”

‘Anna Maria Maiolino’

Where: Museum of Contemporary Art, 250 S. Grand Ave., downtown Los Angeles

When: Through Dec. 31

Info: moca.org

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

How Mexico's súper rudas 'Radical Women' are rewriting the history of Latin American art

Firecrackers, a striptease scandal and more moments of change from the Hammer's 'Radical Women'

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.