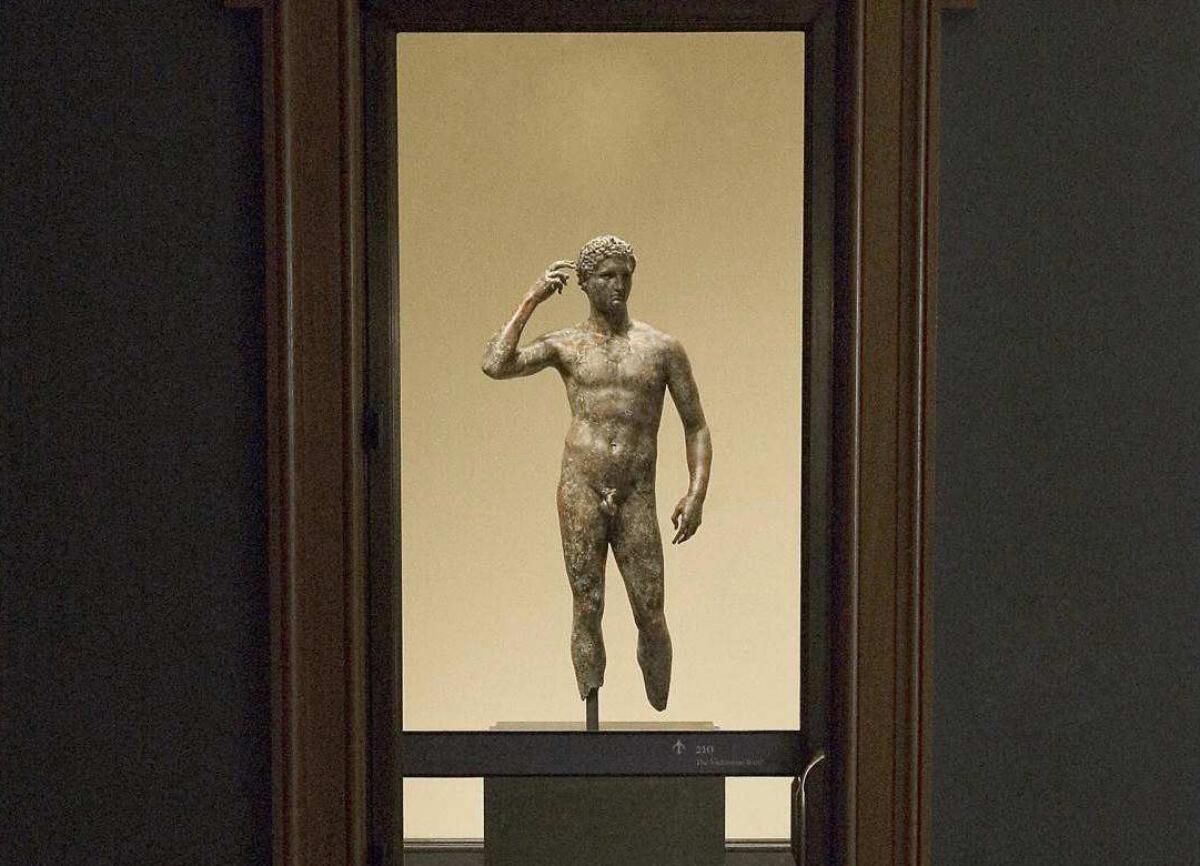

The Getty’s ‘Victorious Youth’ is subject of a custody fight

One of the Getty’s most prized ancient artworks is hanging in a legal balance this week in Italy’s highest court, leaving the L.A. museum’s leaders feeling as if they have landed in a Franz Kafka tale, a judicial and bureaucratic nightmare they can neither understand nor escape.

But unlike a hapless Kafka character, the Getty has an inkling as to why its nearly life-size statue, known as “Victorious Youth” or the “Getty Bronze,” is back in a maze of judicial and investigative proceedings. And rather than suffer passively, the Getty — the world’s richest art institution, with a $6-billion endowment — may well draw a line.

The story begins in 1964, when Italian fishermen snared “Victorious Youth” from the international waters off Italy’s Adriatic coast and brought it to land for the first time in more than 2,000 years.

Believed to have been hewn and cast in Greece, possibly by Lysippus, the personal sculptor to Alexander the Great, the bronze statue apparently was being transported by ship and lost at sea. It is so beautiful, so well preserved, so rare of its kind and so delicate that it commands a climate-controlled room of its own at the Getty Villa antiquities museum in Pacific Palisades. It went on display in 1978, a year after the Getty Trust bought it for $3.95 million, the equivalent of $15.4 million today. In the Getty’s view, it is far too fragile to be moved or exposed to heat and humidity. It remains a must-see for more than 400,000 visitors a year.

The Villa has considerably fewer must-sees nowadays. Since 2006 the Getty has sent more than 40 prized works back to Italy and Greece, conceding that they likely had been looted from their native soil and illegally smuggled and sold. But the Getty insists that “Victorious Youth” is clean, that this story is quite different.

Current Getty leaders concede that some of their precursors, in an eagerness to land ancient masterpieces, had overlooked evidence of looting. That willful blindness fueled by acquisitiveness hardly was endemic to the Getty; New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and others in America went down the same path of repatriating antiquities after being confronted with evidence of looting. The old approach of buy first, ask questions later (if at all) has been replaced since the late 2000s by new museum-world standards mandating cautious deliberation and an exacting study of a prized object’s past whereabouts. New acquisition policies that the Getty adopted in 2006 have been widely praised as exemplary.

In an interview Tuesday, Stephen Clark, a Getty Trust vice president and its top lawyer, wouldn’t go so far as to say that the museum would defy a ruling against it this week in Rome, where the Court of Cassation is expected to deliberate the case in a closed session beginning Wednesday. How to proceed if the court orders the Getty to hand over the statue would be up to the Getty Trust’s board, Clark said.

But Clark and Ron Hartwig, the Getty’s chief spokesman, laid out the museum’s argument for why the bronze youth differs from the huge, otherworldly “Cult Statue of a Goddess” or the carving of two mythical winged predators known as griffins savaging a doe, both of which were sent back to Italy, or a golden funeral wreath returned to Greece.

The Getty’s case for keeping “Victorious Youth” boils down to a couple of principles. One is finders, keepers. If you find something whose owner is unknown and can’t be tracked down, you can do with it as you wish — including sell it to an art dealer or a prominent museum. The other is double jeopardy. Once a case has been decided in court and the accused found not legally culpable, he said, the matter should not be tried again.

“This is one of the frustrations of this whole process,” Clark said of the Italian courts. “One never seems to reach the end.”

Authorities trying to claim the bronze as state property failed to prevail in cases decided by courts in Italy in 1970 and 2007. But a prosecutor in the Marche, the Italian region where the “Victorious Youth” briefly came ashore at the port of Fano and was placed in hiding — at first in a bathtub and then in a cabbage patch, according to past testimony — filed a new claim in a regional court. “It was essentially a do-over,” Clark said.

Two leading American experts on art law said this week that the Marche prosecution seems pointless.

“I’m baffled by this,” said Stephen Urice, a professor at the University of Miami School of Law who’s an expert on art law and cultural property law. “Even if you apply our ethical norms today, I don’t see a problem.”

Patty Gerstenblith, a leading advocate of protecting archaeological sites and sending looted art back to nations of origin, said that “Victorious Youth” shouldn’t be considered a looted work and needn’t be returned. Italy never had a legally valid ownership claim, she said, because the statue wasn’t found in Italian waters or on Italian soil, and it wasn’t made or owned by modern Italy’s Roman and Etruscan forebears.

Gerstenblith, a professor at DePaul University in Chicago and director of its Center for Art, Museum and Cultural Heritage Law, said the fishermen who netted the statue did break Italian laws by hiding their find instead of reporting it to authorities. So did the original buyers who shipped “Victorious Youth” out of Italy without a proper export permit.

Although those illegalities raise ethical questions that might make a museum in 2014 steer clear of a purchase, Gerstenblith said, they have no bearing on the fishermen’s right to have owned and sold the bronze statue, or the Getty’s right to keep what it bought.

Clark said Italian courts and Italian and German investigators have been over this terrain before — first in the late 1960s and 1970, when Italy’s highest court found no reason to declare the statue Italy’s property, again in a 1973 police investigation when the bronze had landed in Germany and J. Paul Getty was mulling whether to buy it, and once more in 2007, when a regional court in the Marche decided a prosecutor’s request to have the statue declared Italian property was not valid because the legal deadline for recovering allegedly stolen property had passed.

But local prosecutors kept trying, and in 2010 the regional court reversed its previous decision and ordered the Getty to return “Victorious Youth” to Italy. The Getty appealed and, after subsequent twists and turns, it’s now up to the high court in Rome.

Derek Fincham, a professor at South Texas College of Law in Houston who focuses on art law and cultural patrimony, thinks the Italians who want the statue have good reasons to persist. For him, the clear subterfuge that took place in the mid-1960s after “Victorious Youth” reached land makes it ethically damaged goods that should be returned.

“If you think about the path the bronze likely took — found by accident, hidden in a bathtub and cabbage field — it’s not the way a masterwork of antiquity should be treated,” he said. “Museums need to be held to a higher standard.”

If the Italian high court doesn’t rule in the Getty’s favor, and the Getty defies the ruling, could that mean the end of almost seven years of peace between Italy and the L.A. museum?

Italy played hardball with the Getty in the mid-2000s, charging its former antiquities curator, Marion True, with conspiring to acquire stolen goods. Prosecutors proceeded slowly and eventually let the case against her lapse. Italy also threatened to end all art loans and other cooperation with the Getty, asserting the leverage that comes with holdings that include some of Western civilization’s greatest art.

The Getty agreed to return the disputed antiquities, and Italy began lending masterpieces that Southern Californians otherwise might never have seen.

“I don’t think we’re going to be at loggerheads,” Clark said, regardless of how the Italian court ruling comes down. “We have really good relations with Italy’s culture minister and our museum colleagues throughout Italy and Sicily. I don’t think an embargo [on art loans from Italy] would serve anybody’s interest, and none of our colleagues [in Italy] have even whispered about anything like that.”

Urice, the Miami art law expert, said that obscure political motives in Italy could have something to do with what to him has been a puzzlingly persistent chase after “Victorious Youth.”

In February, Italy’s former government fell and its Democratic Party gained power. One member of the ruling party is Gian Mario Spacca, president of the Marche region, who has pushed for the return of “Victorious Youth.” Others include the new prime minister, Matteo Renzi, and the new minister of culture, Dario Franceschini.

Hartwig said he met Spacca when he came to the Getty in 2011 with a proposal for mutual ownership of “Victorious Youth.” The Getty declined, citing court proceedings that now appear to be coming to a head.

“It was heartening, a good conversation. It wasn’t ‘J’accuse,’” Hartwig recalled. “It was ‘Let’s do something together.’”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.