Column: Obama Presidential Center greeted with excitement and wariness on Chicago’s South Side

Reporting from Chicago — When we last checked in on plans for the Barack Obama Presidential Center, in early May, architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien had just unveiled preliminary designs for the three-building campus in Jackson Park, on the South Side of Chicago.

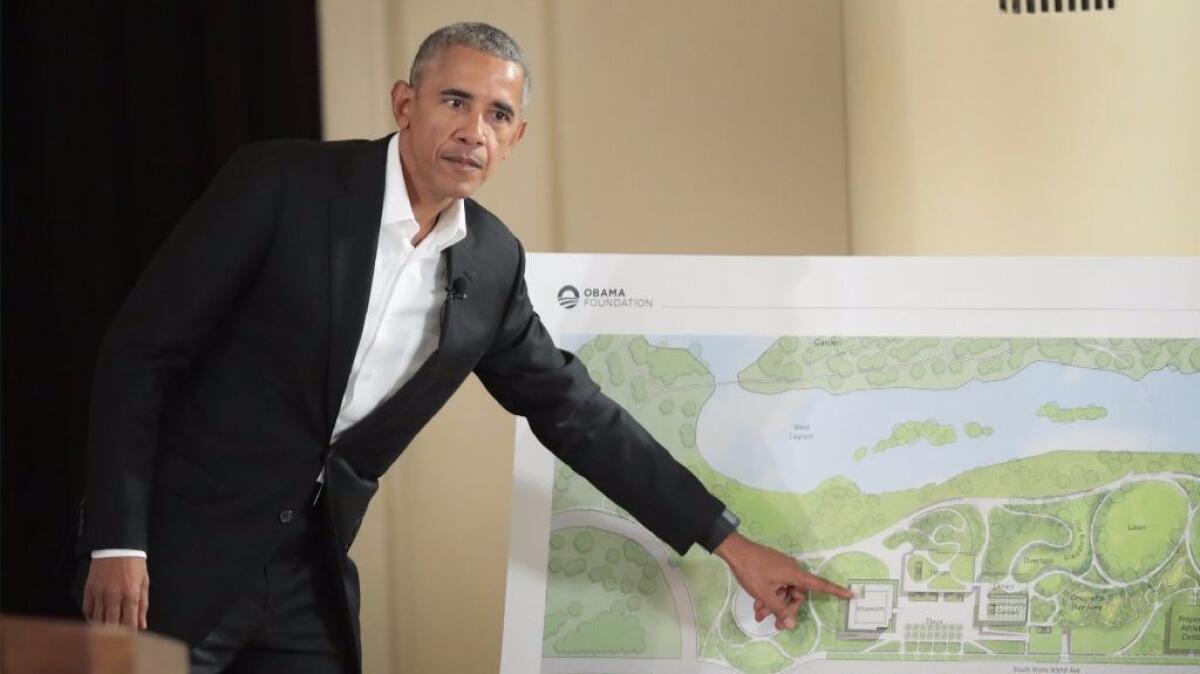

In architectural terms the proposal has barely inched forward since, at least in terms of what’s been shared with the public. (It is officially a “Presidential Center” and not a “Presidential Library” because Obama plans to operate it without help from the National Archives.) But a debate about the role it will play on the South Side, economically and in terms of urban planning, has been heating up in Chicago. The Obama Foundation, which is overseeing planning and fundraising efforts for the project, held a public event earlier this month at McCormick Place, the giant convention center on the Near South Side, to promote and explain its plans.

It was probably when the high school marching band arranged itself behind a large table-top model of the Williams and Tsien design and started playing fight songs at top volume that I realized that this wasn’t going to be a typical public meeting. A few minutes later the architects — flanked by Louise Bernard, the director of the center’s presidential museum, and landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh — took seats along a stage at the front of the packed auditorium. Obama himself, traveling to raise money for the project, which is expected to cost at least $500 million, was absent. In the audience around me were high school students, community activists and interested neighbors, along with a handful of reporters.

From the beginning, though a predictably boosterish tone prevailed in the presentations, there was a certain edge in the air to go with palpable excitement. A small group of protesters, unhappy that the Obama Foundation had so far refused to sign a Community Benefits Agreement guaranteeing construction jobs and other patronage to neighborhood groups, had gathered near the entrance as the crowd was making its way inside. When it came time to open the event to questions from the audience, the first one — from Jeanette Taylor, a resident of the nearby Woodlawn neighborhood — was a pointed query about the agreement, suggesting that Obama wasn’t doing enough to help the underserved South Side.

Poor Taylor never had a chance. To handle the Q&A, the Obama Foundation produced — surprise! — the former president himself, looking fit and relaxed in an open-necked white shirt and dark blazer, and beamed into the room by satellite. His head, appearing on a pair of giant screens on either side of the stage, was probably 10 feet high. His voice boomed Oz-like through the auditorium.

The foundation had arranged for Taylor to open the Q&A by asking about the Community Benefits Agreement, which struck me at first as an open-minded gesture, a way to confront opposition to the center directly. Looking back, and considering that Obama was waiting to appear via satellite, presumably informed about the nature of her question and ready to grind her argument to bits, I began to see it somewhat differently.

It wasn’t just Obama’s monumental on-screen presence that helped flatten the Community Benefits Agreement challenge. It was also the way in which he used his own resume — his own history as a South Side community organizer — as the ultimate trump card, a rhetorical strategy as effective at drowning out the rest of the room as the brass section in that marching band. Obama said he’d spent enough time on the South Side to recognize the “okey-doke” — his phrase, and one he also used in his White House years — when he saw it. This particular agreement was little more than economic blackmail, he implied; he wasn’t going to sign it.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

The Obama Foundation’s response to criticism about the planned location of the center, expected to open in 2021, has been offered in a similar spirit. To oversimplify only a little, it has been that the Obamas know this part of Chicago better than you do.

The site is along the western edge of Jackson Park, which stretches between the campus of the University of Chicago and Lake Michigan. After the World’s Columbian Exposition was held on the site in 1893, landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux were enlisted to produce a plan for its post-Expo life, building on Olmsted’s earlier designs. (Even now the foundations of some Expo buildings remain underground.) Though the park was repurposed many times over the intervening decades, in recent years it has been returned to a state not so far from the Olmsted and Vaux original.

One afternoon a couple of days after the meeting, I spent two hours walking around the section of Jackson Park where the center will be built. I started my tour of the neighborhood at Williams and Tsien’s 2012 Logan Center for the Arts on the southern edge of the University of Chicago campus, a thoughtful and well-made complex about a mile west of the presidential center site and reportedly one that impressed the former president and first lady as they were picking an architect. It’s topped by a 168-foot-tall tower whose views are somewhat more limited — especially toward the lake — than you might guess. The tower at the presidential center, slated to hold museum galleries, will be 180 feet high.

The west side of Jackson Park itself is a mostly quiet, gently rolling landscape of meadows shaded by oak and maple trees, interrupted here and there with lagoons, walking paths and athletic fields. (A high school football team was practicing on the day I visited.) In urban planning terms, the most consequential element of the Obama plan is a proposal to close a busy six-lane street, Cornell Avenue, that runs through the park along the lakeside edge of the center site.

This is unquestionably a good idea, though some residents I spoke with worry — I think rightly — that once Cornell is closed there will be pressure to widen the next street to the west, Stony Island Avenue. That would have the effect of separating the Obama campus from the very South Side neighborhoods it promises to help activate. (Preservationists have also pointed out that Cornell, in much narrower form, is part of the original Olmsted-Vaux design.) As much as I’ll be watching to see if Williams and Tsien can enliven the gloomier aspects of the center’s architecture, which I wrote about in the spring, I’ll be paying attention to how Van Valkenburgh treats the edge of the campus along Stony Island, a street now quiet enough that those high school football players jog right across it from their apartments while barely having to worry about car traffic.

During the McCormick Place meeting, Bernard, the museum director, called the project “the first truly urban” presidential center, a “creative commons” whose core mission is “civic engagement.” Yet it became clear to me, walking through Jackson Park, that the plan is a compromise between the largely suburban presidential libraries of the recent past, which nearly all rise from tabula-rasa sites and have room to spread out, and a full embrace of the South Side’s urban grid. The center’s closest neighbor to the south will be a new golf course designed by Tiger Woods, set to open in 2020. The George W. Bush Presidential Center, on the campus of Southern Methodist University in Dallas, occupies similarly in-between territory.

A truly urban Obama Center would have taken advantage of the many empty lots in the heart of the South Side or — and this would have been a truly inventive leap — threaded new architecture through a collection of empty or underutilized existing buildings in a part of the neighborhood desperate for an economic and architectural boost.

In that sense the debate over the center’s urban and architectural character is not so different from the debate we’re all familiar with about Obama himself. There’s no doubt that putting his presidential center on the South Side of Chicago was in many ways a transformative choice, both for the neighborhoods nearby and for the larger conception of how presidents frame their post-White House careers. At the same time, this is a project that in all sorts of ways hews closely to convention. It fills a site as nearly as convenient for golfers driving in from the suburbs as South Side residents. It gobbles up more acres than it needs to. The Obama Foundation hasn’t been afraid to use old-fashioned political muscle to win support for it, a campaign helped by the fact that Obama’s former White House chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, is now in his second term as Chicago mayor.

The Obama Presidential Center will be transformative, just as it will be truly urban, only up to a point. It’s bound to disappoint anybody who forgets that Obama’s political strategy, as distinct from his larger role in the culture, has always been unshakably centrist. Because (among other reasons) his race continues to make him a lightning rod, a magnet for unhinged opinion, he has preferred the middle to the edge. To the degree that the center will be an architectural portrait of Obama, it will be a fitting one, a gift to the South Side presented very much in his image and on his terms.

Building Type is Christopher Hawthorne’s weekly column on architecture and cities. Look for future installments every Thursday at latimes.com/arts.

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

MORE ARCHITECTURE:

Review: ‘Make New History,’ the second Chicago Architecture Biennial

Building Type: Apple, Amazon and the American city

Herzog & de Meuron’s plans for a campus near L.A.’s Getty Center

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.