‘Power Rangers’ at 30: How a show with Japanese monsters and teen drama captured a generation

It’s hard to imagine TV without an intergalactic dinosaur robot teen drama. Yet, that’s how children’s television was in the U.S. until Aug. 28, 1993, when the first episode of “Mighty Morphin Power Rangers” hit the airwaves and forever changed pop culture.

A year prior, Fox had established itself at the top of cutting-edge children’s programming with its Fox Kids block, which included shows like “X-Men” and “Batman: The Animated Series.” “Power Rangers” debuted with a pilot episode, “Day of the Dumpster,” and it was the start of a phenomenon. It would become one of the most iconic shows, and it continues to capture children’s imaginations three decades later — it’s 29th season, “Power Rangers Dino Fury,” premiered on Netflix in 2022.

Haim Saban, an Israeli American mogul and entrepreneur, was the mastermind behind “Power Rangers.” By the mid-’80s, Saban already had successful ventures in international touring and music industries, and he became a major name in television music after he moved to Los Angeles. At the end of the decade, he founded Saban Entertainment, where he helped create cartoons that infiltrated Saturday morning lineups.

Some were single-season, kid-friendly versions of existing intellectual property like “The Karate Kid” or “Little Shop of Horrors,” or they had a famous name or group attached like “Kid ‘n Play,” an animated series based on the hip-hop duo of the same name, and “Camp Candy,” which featured actor John Candy. Around this time, Saban discovered a Japanese franchise called “Super Sentai” that featured fantastical giant monster fights that he thought would be perfect for U.S. audiences.

Hollywood didn’t believe in the power of teenage superheroes in spandex suits.

Saban spent several years pitching the idea, but no network was interested — until Saban Entertainment had its first hit with 1992’s “X-Men.”

“X-Men” quickly became one of Fox’s top-rated kids shows. It reintroduced Marvel’s mutants to a new generation, something that Margaret Loesch, the president of Fox Kids, had attempted a few years before when she was president and chief executive of Marvel Productions. Loesch had also pitched American adaptations of the “Super Sentai” franchise with no success.

After the successful launch of Fox Kids, when Loesch was looking for counter-programming for the 7:30 a.m. weekday slot, Haim brought her some of the same footage. Loesch took the idea to then-Fox President Jamie Kellner, who expressed his doubts, but he told her to shoot a pilot and if it tested well, they could move forward.

According to a 2019 interview with the Television Academy Foundation, Loesch said the pilot tested well with young boys and girls, and when she saw that the girls at the screening each had their own favorite woman on screen who could “kick butt,” she knew she had a hit.

Although the pilot was cast under the name “Phantoms” and filmed under the title “Dino Rangers,” crew members at some point during shooting were informed that they needed a different name.

The desire was to come up with four-word title: “Something Something Power Rangers,” with those two words eventually being “Mighty Morphin.” The pronunciation became a bit of a challenge for composer Ron Wasserman, one of Saban’s in-house musicians who created the music for the pilot, who said he had to make a conscious effort not to say “morphine.”

In an interview with the Village Voice in 2013, Wasserman said the only input he was given was a suggestion to use the word “go” in the theme song because it had been successful in the “Inspector Gadget” theme song. Wasserman then decided to do a rock theme, creating the show’s iconic guitar riff and the memorable chorus “Go Go Power Rangers!” The theme song was cranked out in 2½ hours, and Wasserman said Haim told him that Fox went crazy over it and that the recording with his vocals would be on the show.

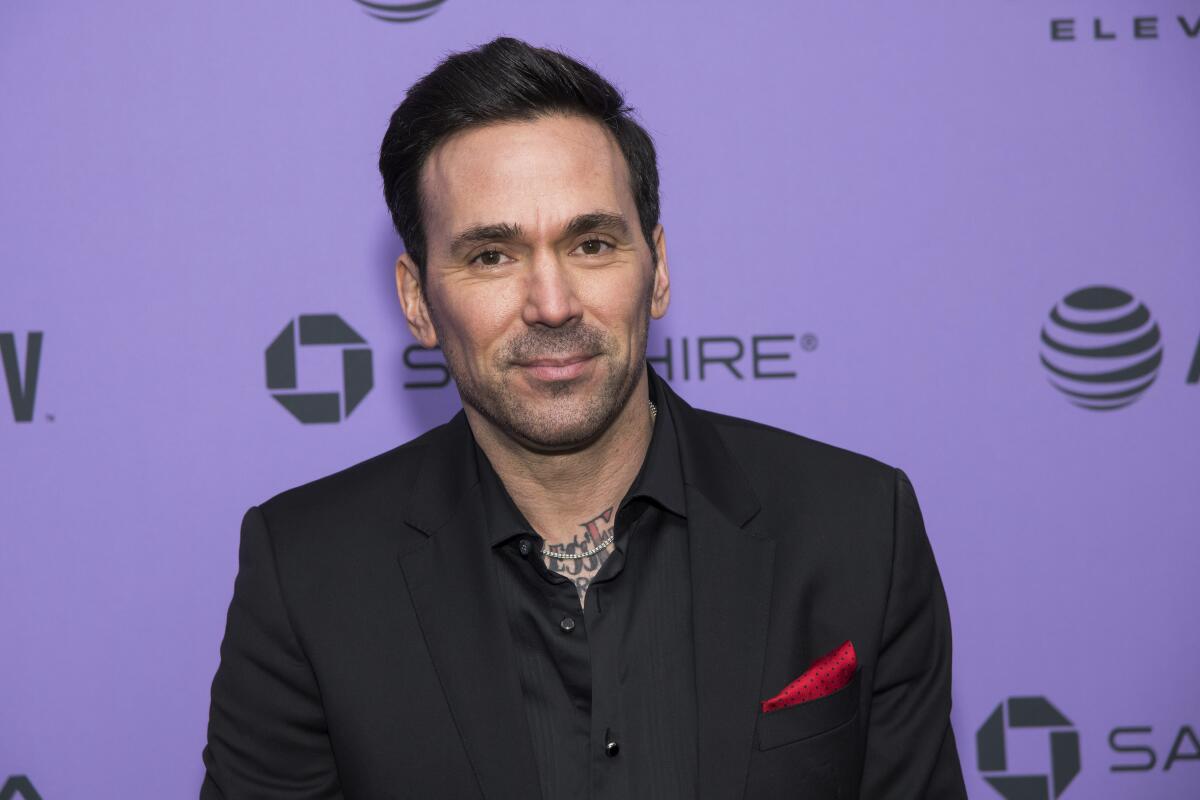

Once the show was picked up, enough changes had to be made to warrant the entire pilot being reshot, the first of many changes the show would make during its production. One of the changes was replacing an actor from the pilot with Jason Narvy, who would play Skull, one the show’s teenage antagonists. Although he had auditioned for a part as one of the lead Rangers, he was called back for the bully role.

In a recent interview, Narvy said that when Haim saw the characters, he said: “These guys are morons … I want them in every show.” Narvy was hired on a Thursday, and the show began shooting the following Monday, only three months after the original pilot episode — which never aired on TV — was shot.

That fast-paced shooting schedule, coupled with cast members not having seen much, if any, of the Japanese footage, led to confusion on set about what they were making.

The actors also didn’t realize how quickly the show’s popularity was rising. Walter Emanuel Jones, who played the original Black Ranger Zack Taylor, said he was recognized as the character a week before the show premiered when a child, who had purchased his action figure, recognized him. It was news to Jones, who responded by saying: “I have a doll?” He said the child answered matter-of-factly: “Yeah, and your face is on the box.”

Those toys proved to be an indicator of how big the show was going to become. Scott Holm of Minnesota, a lifelong Minnesota resident, won the Fox Kids’ Power Rangers sweepstakes in 1993 when he was 7, and he was awarded every Power Rangers toy on the market. He said he was so excited that he didn’t want to go to bed the night he took home his prizes.

“Power Rangers was the thing that everyone was talking about at school,” Holm said. “From the first toy commercial all the way to the premiere of the show, everyone was hooked. We pretended and played Power Rangers on the playground, fighting about who got to be which Power Ranger … you have exactly what a 7-year-old kid in the ’90s was looking for.”

Within two months, the show was reaching 4.3 million children, according to a Fox spokesperson in 1993. By the end of Season 1, the average was 4.8 million, followed by Season 2, which averaged 6.9 million. When the Los Angeles Fox affiliate made the choice to air the show at 3 p.m., it would frequently have higher viewership than “The Oprah Winfrey Show.”

The show was polarizing among critics, particularly because of the martial arts and robot-monster fights, though each episode had a moral message at the end. Carole Lieberman, a media psychiatrist and clinical professor of psychiatry at UCLA, told the Baltimore Sun in 1993: “It’s a harmful show for kids because of its highly violent content. But worse than that, it’s schizophrenigenic [crazy-making] because of the hypocrisy it demonstrates presenting a half-hour of violence and then trying to undo it in 30 seconds.”

Still, while others celebrated the show for being an absurd bit of offbeat camp, it was a hit with children, including a demographic that was 40% female at a time when most of Fox Kids’ programming was averaging only 20% female.

The series featured women as strong lead characters, including Amy Jo Johnson as Kimberly Hart, the Pink Ranger, and Thuy Trang as Trini Kwan, the Yellow Ranger, and it was one of the many ways the show was different. Many elements of that can be found in the performances of the cast. Jones’ character frequently incorporated hip-hop dancing into his martial arts moves — something that other children’s series might have been hesitant to include because of how the genre was perceived at the time — gangsta rap was at its peak with rappers like the then-named Snoop Doggy Dogg on the charts and in the headlines. But Jones said adding hip-hop touches to his character was welcomed.

“Once the show came out, we got sponsors that were sending them [wardrobe], so there was this plethora of things I got to choose from. I’d be like, ‘Ooooh, I like this Malcolm X vest,’ and wear that,” Jones said. “As long as I had black on, I had a variety of vibes to choose from. It was all very Afrocentric, it was all very hip-hop, and I was excited about that as that gave my whole wardrobe a flavor that I hadn’t seen on television before.”

While the actors were able to express their individuality, the cast wasn’t unionized — Saban Entertainment used nonunion labor to keep costs down, according to the Washington Post — and they were required to be together a lot. Fox had ordered 60 episodes that first season (initially 40, followed by an additional 20 after it became a hit), which led to a unique and rigorous method of television production. The shooting was scheduled in four-episode clusters where the live action was filmed to bridge it together with the licensed Japanese footage. Five days a week were on-set, and the sixth was in a recording studio for additional audio voice-overs.

Although cast members did get Christmas 1993 off (having filmed right up to Christmas Eve), the schedule and expectations were such that the actors were still called to set to film on the day of the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

Jones recalls the disbelief he felt about being called into work after the catastrophic event that ground Los Angeles to a halt: “I think we all arrived at the parking lot of the set and sat around waiting for someone to OK the building, and at the end of the day, the building was not OKd, so we turned around and went home.”

The next month, cast members would also cause a citywide disruption when high demand caused them to move a special appearance at a single, small theater to the Universal Amphitheater for six shows. It brought 35,000 people to the Universal Studios theme park and caused an eight-mile long traffic jam.

“Once the Universal Studios things happened, where they started [originally planning] a small 15-minute event as part of D.A.R.E., saying, ‘Hey kids, don’t do drugs,’ and that closed down the L.A. freeway system, we were all like, ‘How did this happen?’” Narvy said. He added that the moment felt even more surreal shortly after. “Meanwhile, once the season was over and we stopped pulling in the paychecks, we were back to doing dinner theater for $20 a performance.”

While Narvy had one of the longest tenures on the show, Season 2 saw the first shift as three of the original Rangers, including Jones, departed the show. Jones soon after entered the realm of Nickelodeon when he was cast in the sci-fi show “Space Cases,” a set he recalls being considerably different.

“It was union. The pay was substantially different, the hours we could work were substantially different, our breaks were scheduled — it was completely different,” he said. (It’s worth noting, according to an April 2023 piece in the Guardian, that following Hasbro’s 2018 acquisition of “Power Rangers,” the show became union affiliated.)

What’s also changed in those years since was how much convention culture had a positive effect on the actors, the fans and the legacy of the show. Jones was among the very first, along with Austin St. John (the Red Ranger, Jason Lee Scott) and the late Trang (the actress died in an accident in 2001), to interact with fans, appearing at car shows in the mid-’90s, where he realized the effect those interactions had. He spread the word to Jason David Frank (the Green Ranger, Tommy Oliver, who died in 2022) and introduced him to his manager, who began helping Frank secure convention bookings. Jones says the inaugural Power Morphicon, a biannual “Power Rangers” convention that started in 2007, was when he first started realizing the long-term effect the franchise had had on its audience, and it contributed to the positive feelings he has toward his time on the show today.

Frank would eventually be credited as one of the most visible and encouraging ambassadors of convention culture, fully embracing what those panels and appearances meant as an experience for fans.

“He understood that Comic-Cons were a form of entertainment,” Narvy said of his co-star. “He understood that it wasn’t about celebrating something that happened, but continuing to make something happen. Being at the Comic-Con was about being at the Comic-Con, making it an event. He embraced that he was there as an entertainer, not a celebrity. And he did not let his fans down.”

The influence of “Power Rangers” on millennials is one whose seeds continue to blossom three decades later. While a handful of shows before “Power Rangers” utilized vintage or stock footage and inserted characters into them, perhaps most notably on “Pee-Wee’s Playhouse,” it was always done with some sort of wink to the audience. The way “Power Rangers” incorporated film from two different sources to create a single cohesive narrative helped destigmatize sampling and normalized a practice that is now commonplace in mash-up culture.

It also changed how children perceived different communities.

“‘Power Rangers’ was showing how much cultures have in common, and more importantly a culture ‘over there’ is not a foreign culture; it’s just a culture you haven’t experienced,” Narvy said. “Things are not strange if you like them, and it’s introducing it to children as they’re learning their norms. What’s normal for being a woman? You can be a superhero; it’s normal, nothing wrong with that. Not only are they seeing a diverse group of people and Japanese vernacular and a time-tested formula, they’re doing it effortlessly. Therefore, you have a whole generation growing up thinking there’s nothing strange about it.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.