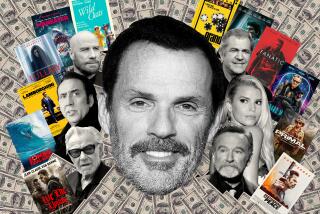

He believed in ‘Power Rangers’ when nobody else did, and it turned him into a billionaire

Hollywood didn’t believe in the power of teenage superheroes in spandex suits.

But Haim Saban would not give up.

The cartoon-music man spent eight years peddling his “Mighty Morphin Power Rangers,” a remake of a Japanese action show about ordinary teenagers who take on supernatural strength to battle bizarre creatures from space. “Every selling season, I would go out and offer it to the networks — and would get kicked out of the room,” Saban said of his 1980s slog. “They told me how crazy I was.”

Despite howls that the live-action show looked cheap, contained too much violence and had ridiculous plots (a ravenous pig from Mars flies to Earth to devour the food), Fox bought the show in 1993. It was a monster hit — thrilling legions of hyperactive boys and girls who emulated the rangers’ kicks and karate chops.

Now after 23 years, 831 television episodes and billions of dollars in sales of “Power Rangers” toys and other merchandise, a $100-million reboot arrives in movie theaters this week. The film will be a crucial test of the staying power of the faded franchise.

Haim is one of the most charming people you’ll ever meet. I’ve always admired him. He is an astute businessman.

— CBS Corp. CEO Leslie Moonves

For Saban, the Power Rangers have long been his trusty sidekicks, catapulting him into the Hollywood limelight. To coincide with the movie premiere, the Israeli American mogul on Wednesday will receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame — another notch in his noisy and kinetic career.

A shrewd deal maker, Saban has parlayed audacious bets into vast wealth and political influence. Forbes estimates his worth at $3 billion. His empire includes interests in real estate, apps and online games, an Israeli phone company, Asian TV channels and an ownership interest in the struggling Spanish-language media company Univision Communications, of which he serves as chairman.

“Many people underestimate him,” said fellow mogul Peter Chernin, the former Fox president who now runs his own entertainment firm. “But if you look at his career, Haim has been at the forefront of where big trends and opportunities are heading.”

Saban also is among the nation’s most prolific political donors, giving $15 million to Hillary Clinton’s failed campaign for president. He financed construction of the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters in Washington and launched the Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution. He’s a staunch supporter of Israel and its ties with the U.S.

In his stately 26th-floor office in Century City, a bank of TV screens shimmers in a wood-paneled wall. A U.S.-based Israeli news channel plays on a large TV, surrounded by smaller screens tuned to CNN and Univision. More than a dozen photos of Saban and wife, Cheryl, mixing with dignitaries adorn a credenza, a testament to his connections.

“Haim is one of the most charming people you’ll ever meet,” CBS Corp. Chief Executive Leslie Moonves said, noting the two have been friends for a quarter of a century. “I’ve always admired him. He is an astute businessman.”

Saban has long cultivated friends in high places. The hack of Clinton campaign emails, revealed by Wikileaks last fall, showed how Clinton’s inner circle valued Saban’s occasional counsel, including his advice on how to reach out to Latinos.

Since the election, he has been busy forging a new relationship — with Jared Kushner, the son-in-law of President Trump who has a prominent role in the White House, helping steer foreign policy.

During the annual Saban Forum at the Bookings Institution in December, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu even suggested the mogul use his platform to initiate Middle East peace talks.

“Next time,” Saban quipped.

Humble beginnings

He blazed an improbable path. When Saban was 12, his Jewish family fled his native Egypt amid political tensions, resettling in Tel Aviv, where his father eked out a living. “He sold pencils, door to door, and sometimes he even had erasers,” Saban said.

His formal education ended with a high school diploma. He served in the Israel Defense Forces and joined a band, much to the dismay of his father who dreamed of his son becoming a lawyer — not a bass guitarist (“A lousy one,” Saban added.).

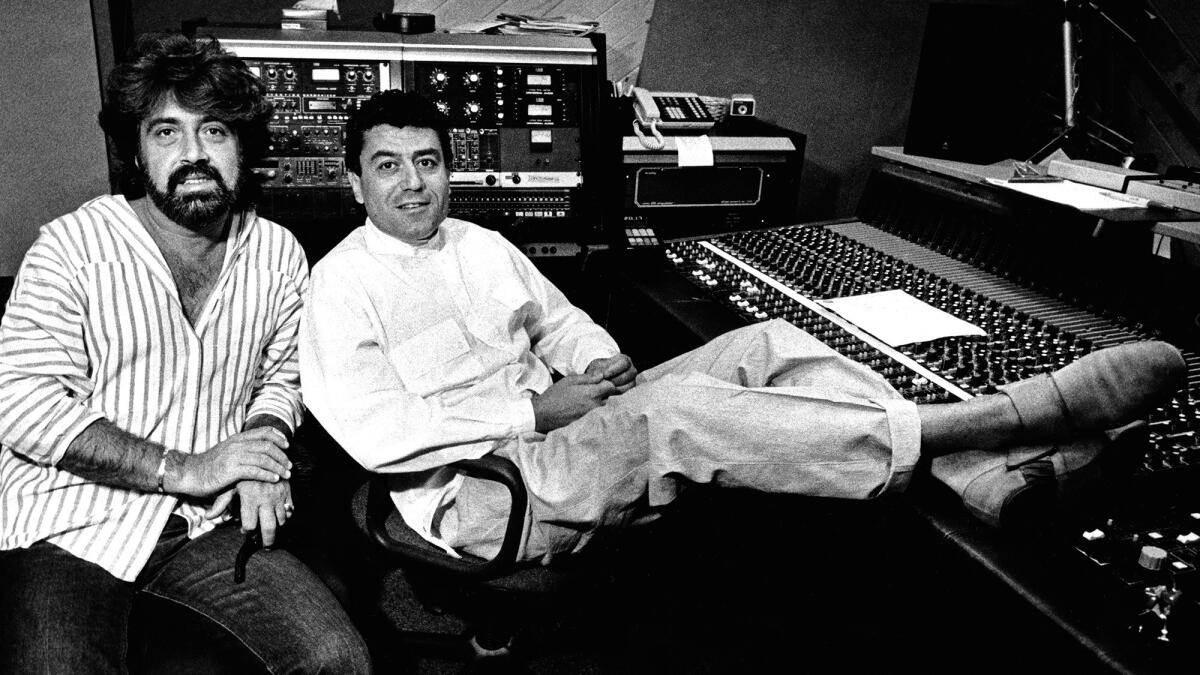

He thrived as a concert promoter, then as a record producer in Paris before migrating to the U.S. in 1983. He and his music-writing partner, Shuki Levy, composed zippy tunes for cartoons.

“If someone asked, ‘What do you do for a living?’, I would say, ‘I do music for cartoons,’ ” Saban said, adding that such a statement would provoke “a strong sense of sympathy towards me,” he said. “They thought I was suffering, but let me tell you ... it was a really good living.”

At that time, Hollywood executives regarded Saban as just another two-bit player.

That didn’t faze him.

“He is unbelievably dogged and determined — he will just keep driving until he achieves his desired result,” Chernin said.

Veteran children’s television executive Margaret Loesch added: “No one works harder than Haim.… He can be like a street vendor. If you walk away, he’ll say: ‘Wait, what about this?’ ”

That’s what happened with “Power Rangers.”

“I’m laying in bed in my hotel room in Japan. At the time there is no Netflix, no cable, no nothing — just three channels playing game shows,” Saban said of the serendipitous 1984 business trip. “All of the sudden there were these five kids in spandex fighting monsters. Don’t ask me why, but I fell in love. It was so campy!”

Because the ranger kids wore helmets with masks during fight scenes, Saban figured he could dub the show into English to produce an inexpensive American hit. He acquired the rights, but executives in Los Angeles were unimpressed.

Making a deal

By the early 1990s, Loesch was building the Fox Kids programming block for Rupert Murdoch’s upstart network. In search of material, she visited Saban because he had acquired rights to cartoons from around the world. He already had a few shows on the air, including “Samurai Pizza Cats” and an “X-Men” cartoon for Fox.

He parked her in a conference room with a stack of videocassettes, but none of the shows piqued her interest. She told Saban she was looking for something “quirky and different, with comedy and action” that would appeal to boys.

“He said, ‘Just a moment, dahling.’ Then he ran down the hall,” Loesch recalled. “He literally came running back with a video and he said, ‘Take a look at this, but don’t be mad at me if you don’t like it.’ ”

It was the Japanese original, “Kyoryu Sentai Zyuranger.” Loesch was sold, but her superiors at Fox were not. “They were aghast,” she said. The network head refused to provide the budget necessary to produce the show. “Haim put up the money himself,” she said.

Even with Saban financing production, and saving money by using Japanese footage of fight sequences, the project was on shaky ground. Local TV stations protested, advertisers balked and the Fox bosses pleaded with Loesch to scrap the show.

“I was sweating bullets,” she said. “For a while, it was me and Haim against the world. But Haim has guts. If he believes in something, he will stick with it.”

The show premiered in late August 1993 and became an overnight sensation. Six months later, promoters staged a live event at Universal Studios with the “Power Rangers” actors. Traffic on the 101 Freeway backed up nearly 10 miles to downtown Los Angeles, according to a 1994 Los Angeles Times article. The theme park was overrun by 35,000 excited kids and harried parents who mobbed kiosks to buy “Power Rangers” merchandise.

“It felt like a Beatles concert,” Saban recalled. “Screaming girls … boys, kids going completely crazy.”

By 1995, sales of “Power Rangers” products exceeded $1 billion a year, according to the Licensing Letter trade publication. In recent years, action figures, video games, bedding and other “Power Rangers” products have generated annual sales in the U.S. and Canada of about $200 million.

Saban and Fox formed a joint venture in 1995 by combining their children’s TV properties, including “Power Rangers” and the rest of Saban’s cartoon library. They later added a cable TV channel, Fox Family, but competition was heating up as rivals Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network produced original shows.

Saban figured it was time for an exit. He and Fox agreed to sell their kids business. “To his credit, he created an auction,” Chernin said.

At the annual Sun Valley, Idaho, retreat for moguls in 2001, Saban dangled the bait in front of Walt Disney Co.’s then-CEO Michael Eisner, who was under pressure to bulk up Disney. Disney bid $5.3 billion, including debt, for Fox Family — double Fox’s own estimates for the channel’s value.

Disney executives soon realized they had overpaid and that others hadn’t been clamoring to buy the channel. “It wasn’t as big of an auction as it appeared,” Chernin said.

The deal, however, eventually paid off for Disney, which turned the channel, now called Freeform, into a reliable profit engine.

Other ventures

Flush with $1.5 billion from the Fox Kids sale to Disney, Saban made other big bets. He and a French firm bought Germany’s second-largest TV broadcast group out of bankruptcy in 2003 for about $2 billion. He and his investment group flipped it four years later for about $4 billion, raking in $970 million in profit.

Other big paydays followed, attracting the attention of federal investigators during a wider probe of wealthy individuals’ use of offshore tax shelters. Saban testified on Capitol Hill in 2006, and later paid $250 million to cover back taxes. He blamed a former tax attorney for his troubles.

“I’ve paid a lot of taxes … with a smile,” Saban said.

Saban also is one of Los Angeles’ most generous philanthropists. He endowed the Saban Research Institute at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, helps finance the Saban Community Clinic that provides free and low-cost healthcare and showers for the homeless, a pediatric center at an Israeli hospital, the American Israel Education Foundation, the Clinton Foundation and he is supporting L.A.’s bid for the 2024 Olympics.

Not all his investments have turned golden. The highly leveraged buyout of Univision has been rocky, and a planned initial public stock offering has been delayed for nearly two years. Saban and his private equity partners had wanted to sell their stakes some time ago, but encountered problems. Over the years they have grappled with a staggering debt load, a bitter court battle, and, most recently, plummeting prime-time ratings on the Univision network.

Saban has been deeply involved with management, patching up the relationship with the Mexican programming company that is now an equity partner. He said he is pleased with Univision’s progress and its “positive earnings momentum.”

But Saban wasn’t thrilled with Disney’s stewardship of the “Power Rangers” franchise.

“They neglected it. So I called Bob Iger [Disney’s CEO] and said, ‘You are not doing anything with it, so why don’t you sell it to me?’ ” Saban recalled. In 2010, Saban Brands paid $65 million to return “Power Rangers” to its biggest fan.

On Friday, “Power Rangers,” a co-production with Lionsgate, will premiere. The movie could fall short of expectations with an estimated soft opening of $33 million in domestic ticket sales. Saban expressed concern that Disney’s highly anticipated new film “Beauty and the Beast” could hurt the prospects of his “Power Rangers.”

Nonetheless, retailers have been stocking up on “Power Rangers” toys.

And workers have been polishing the star on the boulevard — near the Egyptian Theatre — etched with Saban’s name.

“At first I thought, maybe it was a mistake, a kind of Oscar-snafu where they give the prize to the wrong person,” Saban said. “I consider myself a cartoon schlepper, and for a cartoon they gave me a star. I’m humbled and grateful.”

ALSO

Charter CEO Tom Rutledge’s compensation package soars to $98.5 million

An MTV pioneer looks to remake media — and himself — for the YouTube generation

‘Beauty and the Beast’ won’t be shown in Malaysia after Disney refuses to cut gay scene

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.